The Changing Hospital Sector in Washington, D.C.: Implications for the Poor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAREER GUIDE for RESIDENTS

Winter 2017 CAREER GUIDE for RESIDENTS Featuring: • Finding a job that fits • Fixing the system to fight burnout • Understanding nocturnists • A shift in hospital-physician affiliations • Taking communication skills seriously • Millennials, the same doctors in a changed environment • Negotiating an Employment Contract Create your legacy Hospitalists Legacy Health Portland, Oregon At Legacy Health, our legacy is doing what’s best for our patients, our people, our community and our world. Our fundamental responsibility is to improve the health of everyone and everything we touch–to create a legacy that truly lives on. Ours is a legacy of health and community. Of respect and responsibility. Of quality and innovation. It’s the legacy we create every day at Legacy Health. And, if you join our team, it’s yours. Located in the beautiful Pacific Northwest, Legacy is currently seeking experienced Hospitalists to join our dynamic and well established yet expanding Hospitalist Program. Enjoy unique staffing and flexible scheduling with easy access to a wide variety of specialists. You’ll have the opportunity to participate in inpatient care and teaching of medical residents and interns. Successful candidates will have the following education and experience: • Graduate of four-year U.S. Medical School or equivalent • Residency completed in IM or FP • Board Certified in IM or FP • Clinical experience in IM or FP • Board eligible or board certified in IM or FP The spectacular Columbia River Gorge and majestic Cascade Mountains surround Portland. The beautiful ocean beaches of the northwest and fantastic skiing at Mt. Hood are within a 90-minute drive. The temperate four-season climate, spectacular views and abundance of cultural and outdoor activities, along with five-star restaurants, sporting attractions, and outstanding schools, make Portland an ideal place to live. -

Consumer Preferences, Hospital Choices, and Demand-Side Incentives

Consumer Preferences, Hospital Choices, and Demand-side Incentives David I Auerbach, PhD Director of Research, Massachusetts Health Policy Commission Co-authors: Amy Lischko, Susan Koch-Weser, Sarah Hijaz (all of Tufts University School of Medicine) Background § The HPC has consistently found that community hospitals generally provide care of similar quality, at a lower cost, compared to Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) and teaching hospitals § Yet Massachusetts residents use AMCs and teaching hospitals for a high proportion of routine care – In 2014, 42% of Medicare inpatient hospital discharges took place at major teaching hospitals compared to 17% nationwide § Massachusetts has promoted demand-side and supply-side strategies to steer care to more cost-effective settings – Demand-side: e.g., tiered and limited network products – Supply-side: e.g., alternative payment models § Still, the percentage of statewide routine care provided at teaching hospitals continues to rise § The HPC sought a deeper understanding of consumer preferences and what incentives might lead them to seek care in lower-cost, high-quality settings 2 Most community hospitals provide care at a lower cost per discharge, without significant differences in quality Hospital costs per case mix adjusted discharge (CMAD), by cohort On average, community hospital costs are nearly $1,500 less per inpatient stay as Source: HPC analysis of CHIA Hosp. Profiles, 2013 compared to AMCs, Costs per CMAD are not correlated with quality (risk-standardized readmission rates) although -

Employee Handbook Can Be Found Under Quick Links on the Intranet

Revised January 2020 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Daviess Community Hospital As an employee of Daviess Community Hospital, whether employed in in the hospital or its physician practices, you now have a very important role in the success of the hospital. Throughout your employment at Daviess Community Hospital, you will be working with the rest of the staff in a team effort to make the hospital a place where patients choose to come for care, where physicians want to practice and where employees want to work. By accepting your new role with a commitment to Daviess Community Hospital values, you will support the hospital’s mission to provide the best heath care services to our patients. At the same time your dedication to Daviess Community Hospital’s values will allow growth and expansion of our services to meet the health care needs of the community, both today and in the future. You should take pride in being a part of Daviess Community Hospital. We are pleased to welcome you as an employee. You are an important member of the staff, carefully selected to work toward the essential goal of providing excellent medical care and friendly service to our patients, visitors and co- workers. This handbook presents an overview of the benefits and working conditions that are part of your employment. Please read it carefully, as it is important to familiarize yourself with your responsibilities as an employee of Daviess Community Hospital. This handbook supersedes all previous handbooks. The information contained in this handbook is not guaranteed and is subject to change. Should you have any questions as to the interpretation of any policies in this manual or regarding other employment matters, please contact your supervisor or the human resources department. -

Sibley Memorial Hospital Johns Hopkins Medicine

Office of the President 5255 Loughboro Road, N.W. Washington, D.C. 200|6-2695 202-537-4680Telephone 202-537-4683 Fax SIBLEY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL JOHNS HOPKINS MEDICINE kwiktag ~ 090 761 843 October 22, 20:~2 Mr. Amha W. Selassie Director, State Health Planning and Development Agency District of Columbia Department of Health 825 North Capitol Street Washington, DC 20002 Re: Certificate of Need Registration Number :~2-3-10 Dear Mr. Selassie: Enclosed please find Sibley Memorial Hospital’s Certificate of Need (CON) application for the Establishment of Proton Therapy Service - CON 12-3-10. We believe that this facility and equipment are vital to our growth and ability to serve this community as we work to fully integrate our oncology services with Johns Hopkins Medicine. Also included with each of the three CONs is a red binder. Documents contained in these binders include items of a competitive nature and equipment detail which fall under non-disclosure agreements. We request these documents be kept out of the public record. We anticipate that this application will be reviewed in the November 2012 batch review of CON applications. We believe that the application is complete. However, if you or your staff need additional information, please contact Christine Stuppy, Vice President, Business Development and Strategic Planning at 202-537-4472. We look forward to working with you through this process. Sincerely, Richard O. Davis, Ph.D. President GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Department of Health State Health Planning and Development Agency Certificate of Need Application Checklist Registration Number: As discussed and agreed, the fpllowing questions (as checked)are to be cor~;’~eted on the D.C. -

Doctors Community Hospital Application for Certificate

DOCTORS COMMUNITY HOSPITAL APPLICATION FOR CERTIFICATE OF NEED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH PROGRAM: 16-Bed INPATIENT UNIT OCTOBER 7, 2016 Table of Contents PART I - PROJECT IDENTIFICATION AND GENERAL INFORMATION .......... 3 PART II - PROJECT BUDGET ....................................... 10 PART III - CONSISTENCY WITH GENERAL REVIEW CRITERIA AT COMAR 10.24.01.08G(3): ................................................. 11 PART IV - APPLICANT HISTORY, STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY, AUTHORIZATION AND RELEASE OF INFORMATION, AND SIGNATURE ...... 67 2 For internal staff use MARYLAND ____________________ HEALTH MATTER/DOCKET NO. CARE _____________________ COMMISSION DATE DOCKETED HOSPITAL APPLICATION FOR CERTIFICATE OF NEED PART I - PROJECT IDENTIFICATION AND GENERAL INFORMATION 1. FACILITY Name of Facility: Doctors Community Hospital Address: 8118 Good Luck Road Lanham 20706 Prince George’s Street City Zip County Name of Owner (if differs from applicant): 2. OWNER Name of owner: Doctors Community Hospital 3. APPLICANT. If the application has co-applicants, provide the detail regarding each co- applicant in sections 3, 4, and 5 as an attachment. Legal Name of Project Applicant Doctors Community Hospital Address: 8118 Good Luck Road Lanham 20706 Maryland Prince George’s Street City Zip State County Telephone: 301-552-8118 Name of Owner/Chief Executive: Phillip B. Down 4. Name of Licensee or Proposed Licensee, if different from applicant: N/A 3 5. LEGAL STRUCTURE OF APPLICANT (and LICENSEE, if different from applicant). Check or fill in applicable information below and attach an organizational chart showing the owners of applicant (and licensee, if different). A. Governmental B. Corporation (1) Non-profit XX (2) For-profit (3) Close State & date of incorporation Maryland; 1989 C. Partnership General Limited Limited liability partnership Limited liability limited partnership Other (Specify): D. -

Hospitalist Burnout PAGE 8 PAGE 12 PAGE 29

JOHNBUCK CREAMER, MD, SFHM KEY CLINICAL QUESTION JOHN NELSON, MD, MHM Scope of services Managing CIED The causes of continues to evolve infection hospitalist burnout PAGE 8 PAGE 12 PAGE 29 VOLUME 21 NO. 7 I JULY 2017 AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SOCIETY OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE Meet the Pediatric hospitalists two newest march toward recognition SHM board members By Richard Quinn HM’s two newest board Smembers – pediatric hospital- ist Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, and perioperative specialist Rachel Thompson, MD, MPH, SFHM – By Larry Beresford will bring their expertise to bear on the society’s top panel. ediatric hospital medicine is moving However, neither woman sees her Pquickly toward recognition as a role as shaping the board. In fact, they board-certified, fellowship-trained see themselves as lucky to be joining medical subspecialty, joining 14 other the team. pediatric subspecialties now certified by “It’s a true honor to be able to sit on the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP). the board and serve the community It was approved as a subspecialty by the of hospitalists,” said Dr. Thompson, American Board of Medical Specialties outgoing chair of (ABMS) at its October 2016 board meet- SHM’s chapter ing in Chicago in response to a petition support commit- from the ABP. Following years of discus- tee and head of sion within the field,1 it will take 2 more the section of years to describe pediatric hospital medi- hospital medicine cine’s specialized knowledge base and write at the University test questions for biannual board exams that of Nebraska in PEDIATRIC CONTINUED ON PAGE 17 Omaha. -

Sweeny Community Hospital Medical Staff Bylaws

SWEENY COMMUNITY HOSPITAL MEDICAL STAFF BYLAWS i TABLE OF CONTENTS PREAMBLE ....................................................................................................................................1 DEFINITIONS .................................................................................................................................2 ARTICLE I NAME AND PURPOSES ...........................................................................................3 ARTICLE II MEMBERSHIP ..........................................................................................................3 2.1 NATURE OF MEMBERSHIP ................................................................................3 2.2 QUALIFICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP ............................................................4 2.2.1 LICENSURE................................................................................................4 2.2.2 DEA REGISTRATION ...............................................................................5 2.3 EFFECT OF OTHER AFFILIATIONS ..................................................................6 2.4 NONDISCRIMINATION........................................................................................6 2.5 BASIC RESPONSIBILITIES OF MEDICAL STAFF MEMBERSHIP ................6 ARTICLE III CATEGORIES OF MEMBERSHIP .........................................................................6 3.1 CATEGORIES .........................................................................................................7 3.2 ACTIVE STAFF -

Monthly Utilization Report October 2019

District of Columbia Hospital Association Monthly Utilization Report October 2019 Overview & Observations DCHA routinely reports occupancy rates for several specialized patient care unit types (pages 15–23 of this report). Occupancy rates are expressed as the monthly average census as a percentage of designated beds. These rates only show occupancy volume as “within hospital.” In the graphs below, we illustrate the “within-hospital” and the “between hospital” occupancy volume. For example, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital has the highest Med-Surg Occupancy rate, yet averages 270 (54%) fewer Med-Surg patients than MedStar Washington Hospital Center (Fig 1). Similarly, Howard University Hospital has a slightly lower ICU occupancy rate than does The George Washington University Hospital (GWUH); yet averages 24 (53%) fewer ICU patients than GWUH (Fig 2). Differences in volume by unit are important to understand as you look at the overall occupancy of a hospital to explore questions such as, why some patients may experience longer wait times before being moved to an inpatient unit. Comparison of Bed Capacity and Occupancy Rate for Acute Care Hospitals, January - September 2019 Figure 1: Med-Surg Beds by Hospital Figure 2: ICU Beds by Hospital Table of Contents Total Admissions ............................................................2 Emergency Department Visits........................................13 Total Discharges.............................................................4 Ambulatory Surgeries.....................................................14 -

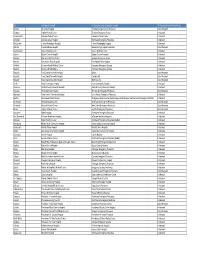

WA ER Physicians Group Directory Listing.Xlsx

City In-Network Hospital ER Physician group serving the hospital ER Physician Group Network Status Tacoma Allenmore Hospital Tacoma Emergency Care Physicians Out of Network Olympia Capital Medical Center Thurston Emergency Group In-Network Leavenworth Cascade Medical Center Cascade Medical Center In-Network Arlington Cascade Valley Hospital Northwest Emergency Physicians In-Network Wenatchee Central Washington Hospital Central Washington Hospital In-Network Ephrata Columbia Basin Hospital Beezley Springs Inpatient Services Out of Network Grand Coulee Coulee Medical Center Coulee Medical Center In-Network Dayton Dayton General Hospital Dayton General Hospital In-Network Spokane Deaconess Medical Center Spokane Emergency Group In-Network Ritzville East Adams Rural Hospital East Adams Rural Hospital In-Network Kirkland EvergreenHealth Medical Center Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Monroe EvergreenHealth Monroe Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Barton Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital CompHealth Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Staff Care Inc. Out of Network Forks Forks Community Hospital Forks Community Hospital In-Network Pomeroy Garfield County Memorial Hospital Garfield County Memorial Hospital In-Network Puyallup Good Samaritan Hospital Mt. Rainier Emergency Physicians Out of Network Aberdeen Grays Harbor Community Hospital Grays Harbor Emergency Physicians In-Network Seattle Harborview Medical Center Emergency Department at Harborview and -

History of the County's Emeline Street Complex

History of the County's Emeline Street Complex This section provides a chronological history of the County Buildings housed at the Emeline Street Complex and various health care services provided in each of the buildings over the years. Attachment A of this Report [not included in web version] contains a map of the Emeline Street Complex which shows the location of most of the buildings discussed in this section. 1877 A men's infirmary section was constructed at the Emeline site. The building was called the County Poor Farm and housed all manner of ill, infirmed and indigent men. 1885 The infirmary was added to and a second facility was constructed. The second facility -- a two-story building -- was the first County Hospital and accommodated surgical care and provided for chronically ill patients. The hospital was erected on land behind Building D and adjacent to Carbonera Creek which is now a parking lot. This building remained in service for a variety of purposes until 1975 when the County was paid for its demolition. The demolition in this instance involved taking the facility down board by board for the purpose of salvaging and reselling the virgin redwood that was used in its construction. The building was last used by the Community Action Board and housed the original CAB food distribution program which later became Food and Nutrition Services. 1925 In 1925, the original wing of the 1040/1100 Emeline building (Building E "Old County Hospital") was constructed as a modern and larger hospital facility to accommodate the growing need for health care in the community. -

Capital Region Research (CAPRES)

Capital Region Research (CAPRES) ROLE OF OFFICE CAPRES is part of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, which is under the leadership of Dr. Daniel Ford, Vice Dean for Clinical Investigation. The Office of Capital Region Research is led by Dr. Mark Sulkowski, Associate Dean for CAPRES and Jackie Lobien, BSN, CCRP‐CP, Director of CAPRES. The Office of Capital Region Research was established: 1. To foster medical discovery within the Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM) community in the Washington capital region including Sibley Memorial Hospital, Suburban Hospital, and Howard County General Hospital; 2. To nurture research collaborations within the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Health System. 3. Enhance the care and experience of patients by providing opportunities to participate in clinical research at or close to the Johns Hopkins facility in which they receive care. CAPRES provides a dynamic interface for researchers in the Capital Region with several key Johns Hopkins Medicine research entities including the Institutional Review Board (IRB), Office of Research Administration (ORA), and Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network (JHCRN). At each of the CAPRES institutions, CAPRES serves as a central resource for all areas of research oversight and administration including IRB/compliance, contracting, study budgets, research training, recruitment, clinical operations, marketing and finance. CAPRES has been integral in working with ORA to coordinate agreements and budgets for community physicians in private practice to open research studies within the walls of the community hospitals. CAPRES is responsible for the Research Review Committees (RRC) at Sibley Memorial Hospital, Suburban Hospital, and Howard County General Hospital. -

My Journey Into Nursing

JUly 2019 my journey into nursing Dorothy Bybee, RN, MSN/MBA-HC, NEA-BC VICE PRESIDENT OF PATIENT CARE SERVICES/CHIEF NURSING OFFICER Dorothy Bybee has always been drawn to larger organizations. She became the vice attend conferences,” she said. “We are nursing because she likes how it blends president of patient care services/chief also encouraged to be innovative and our science with the art of caring. That’s why nursing officer at Columbus Community ideas are well received. As I have needed she planned on going into the career after Hospital (CCH) in April 2017. new positions and looked at new service high school – but life took her in a different lines, CCH has been supportive.” direction. In this position, Bybee oversees nursing operations in several areas of the hospital, Bybee cited the hospital’s new patient “I started with nursing in mind out of including, inpatient, outpatient, surgery, navigation program that better educates and high school and got sidetracked with emergency department, home health, prepares patients for cancer treatment, as marriage and children,” she said. medical/surgical, obstetrics and wound a great example of new positions that have changed the lives of CCH’s patients. But Bybee hadn’t forgotten her high school care. dream. When her family moved closer to She also oversees the pharmacy, respiratory She is happy to have been part of bringing “jumped at the a nursing program, she therapy, case management, quality, this new service line to the community and chance with three kids in tow.” credentialing, risk management, regulatory she’s happy she ended up in the health care field.