Daniel R. Weinberg Lincoln Conspirators Collection, 1865–1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USCA Case #01-5103 Document #712838 Filed: 11/08/2002 Page 1 of 9

<<The pagination in this PDF may not match the actual pagination in the printed slip opinion>> USCA Case #01-5103 Document #712838 Filed: 11/08/2002 Page 1 of 9 United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued September 3, 2002 Decided November 8, 2002 No. 01-5103 Thomas B. Mudd, Son of Richard D. Mudd and great-grandson of Samuel A. Mudd, as heir and successor to Samuel A. Mudd, deceased, Appellant v. Thomas A. White, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellees Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (No. 97cv02946) Philip A. Gagner argued the cause and filed the briefs for appellant. <<The pagination in this PDF may not match the actual pagination in the printed slip opinion>> USCA Case #01-5103 Document #712838 Filed: 11/08/2002 Page 2 of 9 R. Craig Lawrence, Assistant United States Attorney, ar- gued the cause for appellees. With him on the briefs were Roscoe C. Howard Jr., United States Attorney, Wyneva Johnson, Assistant United States Attorney, and James R. Agar II, Attorney, Office of the Judge Advocate General. Before: Edwards and Rogers, Circuit Judges, and Williams, Senior Circuit Judge. Opinion for the Court filed by Circuit Judge Edwards. Edwards, Circuit Judge: The appellant, Thomas B. Mudd,* whose great-grandfather, Dr. Samuel Mudd, was convicted by a military tribunal for his alleged role in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, seeks judicial review of the Army's refusal to reverse that conviction more than a century later. Appellant bases his claim on 10 U.S.C. -

The Confession of George Atzerodt

The Confession of George Atzerodt Full Transcript (below) with Introduction George Atzerodt was a homeless German immigrant who performed errands for the actor, John Wilkes Booth, while also odd-jobbing around Southern Maryland. He had been arrested on April 20, 1865, six days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. Booth had another errand boy, a simpleton named David Herold, who resided in town. Herold and Atzerodt ran errands for Booth, such as tending horses, delivering messages, and fetching supplies. Both were known for running their mouths, and Atzerodt was known for drinking. Four weeks before the assassination, Booth had intentions to kidnap President Lincoln, but when his kidnapping accomplices learned how ridiculous his plan was, they abandoned him and returned to their homes in the Baltimore area. On the day of the assassination the only persons remaining in D.C. who had any connection to the kidnapping plot were Booth's errand boys, George Atzerodt and David Herold, plus one of the key collaborators with Booth, James Donaldson. After David Herold had been arrested, he confessed to Judge Advocate John Bingham on April 27 that Booth and his associates had intended to kill not only Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, but Vice President Andrew Johnson as well. David Herold stated Booth told him there were 35 people in Washington colluding in the assassination. This information Herold learned from Booth while accompanying him on his flight after the assassination. In Atzerodt's confession, this band of assassins was described as a crowd from New York. -

How Did Booth Break His

STATE YOUR CASE (No. 2), John Elliott: How Did John Wilkes Booth Break His Leg? I believe that John Wilkes Booth did not break his leg when jumping from the balustrade to the stage at Ford’s Theatre. I support Michael Kauffman’s theory that Booth broke his Fibula when his horse fell on him after he crossed in to Maryland. First I will refute the diary entry Booth wrote during his escape, claiming he broke his leg in jumping. Booth’s version of events is filled with exaggerated claims that were written in response to newspaper articles calling him a coward. Next, I will present the first eyewitness accounts taken in the early days after the assassination that state John Wilkes Booth ran or rushed across the stage after jumping from the box. Surely a man who had just broken his leg would show some signs of pain or would limp after breaking his leg. Last, I will present the evidence that I believe shows JWB broke his leg when his horse fell on him. This includes more eyewitness accounts and medical opinions. Sources: We Saw Lincoln Shot Timothy S. Good American Brutus Mike Kauffman The Lincoln Assassination/The Evidence Edwards and Steers Jr. Booth’s Diary Entry History books tell us that John Wilkes Booth broke his leg while jumping from the balustrade of President Lincoln’s box to the stage at Ford’s Theatre. This is the most commonly held belief because John Wilkes Booth wrote that it happened that way. But should we take his word for it? A closer examination of his diary entry shows that he tried to paint a more daring and heroic image of himself during what he believed to be his crowning achievement. -

23 League in New York Before They Were Purchased by Granville

is identical to a photograph taken in 1866 (fig. 12), which includes sev- eral men and a rowboat in the fore- ground. From this we might assume that Eastman, and perhaps Chapman, may have consulted a wartime pho- tograph. His antebellum Sumter is highly idealized, drawn perhaps from an as-yet unidentified print, or extrapolated from maps and plans of the fort—child’s play for a master topographer like Eastman. Coastal Defenses The forts painted by Eastman had once been the state of the art, before rifled artillery rendered masonry Fig. 11. Seth Eastman, Fort Sumter, South Carolina, After the War, 1870–1875. obsolete, as in the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861 and the capture of Fort Pulaski one year later. By 1867, when the construction of new Third System fortifications ceased, more than 40 citadels defended Amer- ican coastal waters.12 Most of East- man’s forts were constructed under the Third System, but few of them saw action during the Civil War. A number served as military prisons. As commandant of Fort Mifflin on the Delaware River from November 1864 to August 1865, Col. Eastman would have visited Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, located in the river channel between Wilmington and New Castle, Delaware. Channel-dredging had dumped tons of spoil at the northern end of the island, land upon which a miserable prison-pen housed enlisted Confederate pris- oners of war. Their officers were Fig. 12. It appears that Eastman used this George N. Barnard photograph, Fort quartered within the fort in relative Sumter in April, 1865, as the source for his painting. -

The Assassination 1 of 2 a Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy

5-2 The Assassination 1 of 2 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy The Assassination Lincoln Assassination. Clipart ETC. 18 July 2008. Educational Technology Clearinghouse. University of South Florida. <http://etc.usf.edu/clipart> March 17, 1865 John Wilkes Booth’s plot to kidnap Lincoln is foiled by Lincoln’s failure to show up at the soldiers’ hospital where Booth planned to carry out the kidnapping. April 14,1865 Booth fires his derringer the President while Lincoln, his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, Maj. Henry R. Rathbone, and his fiancée Clara Harris are in a private box in Ford’s Theater viewing a special performance of Our American Cousin. Entering through the President's left ear, the bullet lodges behind his right eye, leaving him paralyzed. Booth leaps from the box on to the stage, declaring “Sic simper tyrannis” and breaking his right fibula. Nearly simultaneously, Lewis Paine twice slashes Secretary of State William Henry Seward’s throat while the Secretary lies in bed recovering from a carriage accident. A metal surgical collar prevents the attack from accomplishing its deadly objective. Believing his attempt successful, Paine fights his way out of the mansion. Dr. Charles Leale examines the President. Lincoln is moved to a boarding house, now called the Peterson House, across Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. 5-2 The Assassination 2 of 2 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy from the theater on 10th Street. Co-conspirator George Atzerodt fails to carry out the plan to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

The Catholic Conscience and the Defense of Dr. Mudd by Lorle Porter (Concluded, from Vol

Vol. XXXVI, No. 12 December, 2011 The Catholic Conscience and the Defense of Dr. Mudd By Lorle Porter (Concluded, from Vol. XXXVI, No. 11) And his adopted brother William T. Sherman was being puffed as a presidential candidate–the last thing either man needed was association with the political “hot potato” of the day. Prosecutors such as the posturing and violent Ohioan John Bingham, were prepared to use their roles in the trial as political launching pads. Defense attorneys could look forward to nothing but vilification. Attempting to explain Ewing’s decision to join the defense, a 1980 television docudrama The Ordeal of Dr. Mudd, would depict a sequence in which General Ewing, walking down a Georgetown street, overheard a frantic Frances Mudd pleading with an attorney to defend her husband. The following scene showed Mrs. Mudd praying in a non- denominational church, only to be approached by General Ewing with an offer to help. Queried as to why a Union officer would undertake the case, Ewing Dr. Samuel Mudd merely quoted his grandfather’s admonition to follow (Libraryof Congress) an honorable path in life. The scene is fictional, if not In what would become the final month of totally implausible, given Ewing’s “lofty ideals.” the war, March, 1865, Tom Ewing went to However, if placed in a Catholic church, the scene Washington to submit his military resignation to would have been credible, especially in a symbolic Abraham Lincoln, a personal friend. His brother sense. At heart, Ewing undertook the case to defend Bub (Hugh Boyle) was back at Geisborough helping a man of his community. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS NATIONAL MALL & MEMORIAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to our nation’s capital, Wash- return trips for you and your family. Save it ington, District of Columbia! as a memento or pass it along to friends. Zion National Park Washington, D.C., is rich in culture and The National Park Service, along with is the result of erosion, history and, with so many sites to see, Eastern National, the Trust for the National sedimentary uplift, and there are countless ways to experience Mall and Guest Services, work together this special place. As with all American to provide the best experience possible Stephanie Shinmachi. Park Network editions, this guide to the for visitors to the National Mall & Me- 8 ⅞ National Mall & Memorial Parks provides morial Parks. information to make your visit more fun, memorable, safe and educational. -

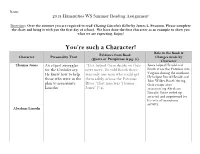

You're Such a Character!

Name:_____________________________________________ 2018 Humanities WS Summer Reading Assignment Directions: Over the summer you are required to read Chasing Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson. Please complete the chart and bring it with you the first day of school. We have done the first character as an example to show you what we are expecting. Enjoy! You’re such a Character! Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Thomas Jones An expert smuggler “Cox helped them decide on their Jones helped Herold and for the Confederacy. next move. He told Booth there Booth cross the Potomac into He knew how to help was only one man who could get Virginia during the manhunt. those who were in the them safely across the Potomac He helped David Herold and John Wilkes Booth during plan to assassinate River. That man was Thomas their escape after Lincoln. Jones” (74). assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Jones ended up arrested and imprisoned for his acts of treasonous activity. Abraham Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Wilkes Booth Edwin Stanton George Atzerodt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Garrett John Surratt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Mary Surratt Mary Todd Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. -

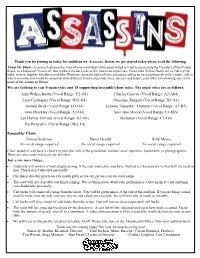

We Are Looking to Cast 9 Main Roles and 15 Supporting/Ensemble/Choir Roles

Thank you for joining us today for auditions for Assassins. Before we get started today please read the following: About the Show: Assassins lays bare the lives of nine individuals who assassinated or tried to assassinate the President of the United States, in a historical "revusical" that explores the dark side of the American experience. From John Wilkes Booth to Lee Harvey Os- wald, writers, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman, bend the rules of time and space, taking us on a nightmarish roller coaster ride in which assassins and would-be assassins from different historical periods meet, interact and inspire each other to harrowing acts in the name of the American Dream. We are looking to cast 9 main roles and 15 supporting/ensemble/choir roles. The main roles are as follows: John Wilkes Booth (Vocal Range: F2-G4) Charles Guiteau (Vocal Range: A2-Ab4) Leon Czologosz (Vocal Range: G#2-G4) Giuseppe Zangara (Vocal Range: B2-A4) Samuel Byck (Vocal Range: D3-G4) Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme (Vocal Range: A3-B5) John Hinckley (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Sara Jane Moore (Vocal Range: F3-Eb5) Lee Harvey Oswald (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Balladeer (Vocal Range: C3-G4) The Proprietor (Vocal Range: Gb2-F4) Ensemble/ Choir: Emma Goldman David Herold Billy Moore No vocal range required No vocal range required No vocal range required Choir members will have a chance to play the roles of the presidents, tourists, news reporters, bystanders, or photographers. There are also some solo parts for the choir. Just a few more things… Auditions will consist of your prepared song. -

The Flimsy Case Against Mary Surratt: the Judicial Murder of One

The Flimsy Case Against Mary Surratt: The Judicial Murder of One of the Accused Lincoln Assassination Conspirators Michael T. Griffith 2019 @All Rights Reserved On June 30, 1865, an illegal military tribunal found Mrs. Mary Surratt guilty of conspiring with John Wilkes Booth and others to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln, and sentenced her to death by hanging. Despite numerous appeals to commute her sentence to life in prison, she was hung seven days later on July 7. She was the first woman ever to be executed by the federal government. The evidence that the military commission used as the basis for its verdict was flimsy and entirely circumstantial. Even worse, the War Department’s prosecutors withheld evidence that indicated Mrs. Surratt did not know that Booth intended to shoot President Lincoln. The prosecutors also refused to allow testimony that would have seriously impeached one of the two chief witnesses against her. Mary Surratt John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln’s assassin. He shot President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington on April 14, 1865. The military tribunal claimed that Mary Surratt: * Knew about the assassination plot and failed to report it * On April 11, 1865, told John Lloyd that the “shooting irons” (rifles) that had been delivered to him would be needed soon 1 * An April 14, the day of the assassination, gave Lloyd a package from Booth and told him to have the rifles ready that night * Falsely claimed that she did not recognize Lewis Payne (Lewis Powell) when he showed up at her boarding house on April 17 * Falsely claimed that her youngest son, John Surratt, was not in Washington on the day of the assassination Two Plots: Kidnapping and Assassination Before we begin to examine the military commission’s case against Mary Surratt, we need to understand that Booth initiated two separate plots against Lincoln. -

Mary Surratt: the Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita History Class Publications Department of History 2013 Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Leah, "Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death" (2013). History Class Publications. 34. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history/34 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Surratt: The Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson 1 On the night of April 14th, 1865, a gunshot was heard in the balcony of Ford’s Theatre followed by women screaming. A shadowy figure jumped onto the stage and yelled three now-famous words, “Sic semper tyrannis!” which means, “Ever thus to the tyrants!”1 He then limped off the stage, jumped on a horse that was being kept for him at the back of the theatre, and rode off into the moonlight with an unidentified companion. A few hours later, a knock was heard on the door of the Surratt boarding house. The police were tracking down John Wilkes Booth and his associate, John Surratt, and they had come to the boarding house because it was the home of John Surratt. An older woman answered the door and told the police that her son, John Surratt, was not at home and she did not know where he was.