Meet David Crane: Video Games Guru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gamasutra - Features - the History of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM

Gamasutra - Features - The History Of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM The History Of Activision By Jeffrey Fleming The Memo When David Crane joined Atari in 1977, the company was maturing from a feisty Silicon Valley start-up to a mass-market entertainment company. “Nolan Bushnell had recently sold to Warner but he was still around offering creative guidance. Most of the drug culture was a thing of the past and the days of hot-tubbing in the office were over,” Crane recalled. The sale to Warner Communications had given Atari the much-needed financial stability required to push into the home market with its new VCS console. Despite an uncertain start, the VCS soon became a retail sensation, bringing in hundreds of millions in profits for Atari. “It was a great place to work because we were creating cutting-edge home video games, and helping to define a new industry,” Crane remembered. “But it wasn’t all roses as the California culture of creativity was being pushed out in favor of traditional corporate structure,” Crane noted. Bushnell clashed with Warner’s board of directors and in 1978 he was forced out of the company that he had founded. To replace Bushnell, Warner installed former Burlington executive Ray Kassar as the company’s new CEO, a man who had little in common with the creative programmers at Atari. “In spite of Warner’s management, Atari was still doing very well financially, and middle management made promises of profit sharing and other bonuses. Unfortunately, when it came time to distribute these windfalls, senior management denied ever making such promises,” Crane remembered. -

What Factors Led to the Collapse of the North American Video Games Industry in 1983?

IB History Internal Assessment – Sample from the IST via www.activehistory.co.uk What factors led to the collapse of the North American video games industry in 1983? Image from http://cdn.slashgear.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/atari-sq.jpg “Atari was one of the great rides…it was one of the greatest business educations in the history of the universe.”1 Manny Gerard (former Vice-President of Warner) International Baccalaureate History Internal Assessment Word count: 1,999 International School of Toulouse 1 Kent, Steven L., (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, Calif.: Prima, (ISBN: 0761536434), pp. 102 Niall Rutherford Page 1 IB History Internal Assessment – Sample from the IST via www.activehistory.co.uk Contents 3 Plan of the Investigation 4 Summary of Evidence 6 Evaluation of Sources 8 Analysis 10 Conclusion 11 List of Sources 12 Appendices Niall Rutherford Page 2 IB History Internal Assessment – Sample from the IST via www.activehistory.co.uk Plan of the Investigation This investigation will assess the factors that led to the North American video game industry crash in 1983. I chose this topic due to my personal enthusiasm for video games and the immense importance of the crash in video game history: without Atari’s downfall, Nintendo would never have been successful worldwide and gaming may never have recovered. In addition, the mistakes of the biggest contemporary competitors (especially Atari) are relevant today when discussing the future avoidance of such a disaster. I have evaluated the two key interpretations of the crash in my analysis: namely, the notion that Atari and Warner were almost entirely to blame for the crash and the counterargument that external factors such as Activision and Commodore had the bigger impact. -

Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow

San Francisco, California August 20-21, 2005 $5.00 Welcome to Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow .... eight years! It's truly amazing to think that we 've been doing this show, and trying to come up with a fresh introduction for this program, for eight years now. Many things have changed over the years - not the least of which has been ourselves. Eight years ago John was a cable splicer for the New York phone company, which was then called NYNEX, and was happily and peacefully married to his wife Beverly who had no idea what she was in for over the next eight years. Today, John's still married to Beverly though not quite as peacefully with the addition of two sons to his family. He's also in a supervisory position with Verizon - the new New York phone company. At the time of our first show, Sean was seven years into a thirteen-year stint with a convenience store he owned in Chicago. He was married to Melissa and they had two daughters. Eight years later, Sean has sold the convenience store and opened a videogame store - something of a life-long dream (or was that a nightmare?) Sean 's family has doubled in size and now consists of fou r daughters. Joe and Liz have probably had the fewest changes in their lives over the years but that's about to change . Joe has been working for a firm that manages and maintains database software for pharmaceutical companies for the past twenty-some years. While there haven 't been any additions to their family, Joe is about to leave his job and pursue his dream of owning his own business - and what would be more appropriate than a videogame store for someone who's life has been devoted to collecting both the games themselves and information about them for at least as many years? Despite these changes in our lives we once again find ourselves gathering to pay tribute to an industry for which our admiration will never change . -

Act-82Catalog

THE ACTIVISION@ ADVENTURE Put an Activision !!> video game into your Atari !!> Video Computer System™or your Sears Tele-Games!!> Video Arcade~ and expect an experience incredibly involving for your mind and senses. Sports games. Strategy games. Action games. And more. All so amazingly realistic, you'll truly believe -we put you in the game. cUV1s10M. Atari• ond Video Computer System™ ore registered trademarks of Atari, Inc. Tele-Gomes* and V1deo Arcade™ ore trademarks of Seors, Roebuck and Co ACTION GAMES Designed by Steve Cartwright. This Designed by Alan Miller. You 're in game is a space nightmare! Imagine, the cockpit of a mighty intergalactic if you can, fighting off multiple waves spacecraft. Your mission : Defend your of the strangest objects ever to defy starbases against attacking enemy Available, the laws al gravity. And there's no starfighters. Galactic charts pinpoint September 1982 rest. Celestial dice, spinning bow-ties, enemy torgets. Meteor showers slow furious flying widgets and even hostile your attack. And enemy particle hamburgers. If it's not one " thing;· cannons can quickly send you limping it's another. And they can drop round home to your orbiting starbase for after round of deadly disintegrators. repairs. Computer reodauts reveal You 'd better hope you ond your energy levels, ship damage and more. courage are wide owoke when you Without a doubt, Starmaster™ by play MegaMonia™ by Activision ~ Activision is one of the most thrilling video game experiences of the yearl 1111111 ifl 'I 'I r - ""' Designed by Dovid Crane. Seek Designed by Bob Whitehead. You're out the lost treasures of an Ancient flying escort far a truck convoy of Civilization hidden deep within the for· medical supplies. -

Activision-Catalog

A l#Jrld ofDifference .· ·:.. ~ \~ :· ;': . .· ":" ~'.'' . ~ ·' .... ""· ~ · ' : !_· .-.. ~ ·:· •• ·: ./' "' -~ ·. .. ... ' :·. ·- ~·,. ~. ·.· .. .. ' . ... ·.:· · ..- ..:. : ·.• ~::- , ___;. -:: : ,\. ' . !,' .. ' -· ' . .. · .• • . • ~ .. 't'. :: ·: ~ ••• .. '"< .._, .-· 1>, • f \. ·. ~. •. ·: · .•·:. _:·:: ..J _~_: : . ... ._: .... :. ... ... ; ·. -::. ~\\!;_ ·_ ~· · :_.~~·:":. .: ..: =.·_,_\_ ,.~ i~·::; '.' .;~; '): . .. ·. · A :· :,- .'· • -~ • ... · _.: : • .f - ~ :.· ~- "' . ~ ·. : ~ :_ ..· · .. - .:_ ~--. : ~ .: .~ . -.·., ..:. ::.>- :. ' .. ~-· ... ·. ~ . ·~ ~- Activision's .· ·'.. Entertainment Software ~ ~· . · ... ·:. -~ .. -· ... .: r'· , ,•• •••• . ~ .. is recognized as the "... best .• . ·.' : . "' . •. - ~:·. HOWARD THE DUCK" . ·' ·. .. -· entertainment line in the business." ~· •, : _... : . ·.. .. This year is no exception. As a follow Adventure on Volcano up to the ever popular Hacker, we've Island" -·. ' . ~ . ; ... , Created by Tray Ly11don, Scott On; Harold Seeley and ... released Hacker JPM: The Doomsday john Cutter. Papers. And the exciting Aliens r~ is coming. Both programs feature the Quack-fu to the rescue. What if your two best friends suddenly ,.: -.. ~ same innovation that has made Activi •.. disappeared? What if they were being sion Entertainment Software the all held prisoner in an active volcano by time favorite of fans. And, with more a dark overlord? What if to save them titles in the works, we're going to keep ..... · you had to fight off an army of mutants? '. it that way. Brave high winds in an -

Digital Press Issue

DIGITAL PRESS THE Bio-degradable Source for Videogamers $ 2 . 0 0 I s s u e 4499 nneutered.eutered. Neutered. Editor’s BLURB by Joe Santulli DIGITAL So here we are, sittin’ pretty just one issue away from a real milestone. 50 issues! But here’s a bit of trivia for you. THIS is really the 50th issue. That’s right, if you’ve been here since the early 90’s you may remember the “Write Digital Press” issue where we asked our readers to submit their own columns and reviews and the rest of us lazy asses just sat back and took a break. Ahh, I need to re-institute that idea again, though as you can see from the frequency of these issues, I pretty much “take a break” 10 months out of the year. About that... I realize that DP has become much less than a bi-monthly ‘zine over the past 2-3 PRESS years and I fi nally know why that is. It was about that time when the DP website started getting popular, the forums started getting busy, and there were more opportunities to reach a wide audience with our “expertise”. So I’ve been hammering away at that, and if you haven’t seen it recently it’s really quite DIGITAL PRESS # 49 lovely, lively, and BIG... at least with regard to content. So here’s what I’ve done SEPT/ OCT 2002 to make BOTH the paper issues and website work at full capacity. I promoted Founders Joe Santulli one of our staff. -

Las Vegas, Nevada August 9-Lo, 2003

Las Vegas, Nevada August 9-lO, 2003 $5.00 • ENMANCED 3D GRAPMICS! • PLAY ANVTIME OFFLINE! • . FULL-SCREEN GAME PLAY! • 2 REALISTIC ALLEYS WITM UNIQUE SOUNDTRACKS! • TROPMV ROOM STORES MIGM SERIES, MIGM GAME, PERFECT GAMES AND MORE! 'DOWNLOAD THE: FREE TRIAL AT SKVWOl;IKS® WElCONIE £ 1HANIC9 Welcome to Classic Gaming Expo 2003! The show is now six years old and still getting bigger and better. We knew it would be hard to beat last year's fifth anniversary spectacular, but somehow this year's show has shaped up to be our best yet. All the while maintaining our tradition and primary goal of producing a show that celebrates the roots and history of videogames that is run BY classic gamers, FOR classic gamers. We have some great things planned this year including a mini-event known as Jag-Fest. Once a seperate event, this year Jag-Fest has taken to the road having multiple events within other shows. Headed up by Carl Forhan, Jag-Fest at CGE looks to be the biggest and best yet! We have several other new vendors who will be joining us this year and showing off their latest products. Keep an eye out for new classic titles from major software publishers like Midway, Ubi Soft, and Atari. The CGE Museum has grown by leaps and bounds this year and is literally bursting at the seams thanks to numerous new items on display for the first time. What makes the museum so incredible and unique is that it is comprised of hundreds of items from various collectors, friends , and some of our distinguished guests. -

3 Ninjas Kick Back A.S.P. : Air Strike Patrol Aaahh!!! Real Monsters ABC

3 Ninjas Kick Back A.S.P. : Air Strike Patrol Aaahh!!! Real Monsters ABC Monday Night Football ACME Animation Factory ActRaiser ActRaiser 2 Addams Family Values Advanced Dungeons & Dragons : Eye of the Beholder Adventures of Yogi Bear Aero Fighters Aero the Acro-Bat Aero the Acro-Bat 2 Aerobiz Aerobiz Supersonic Air Cavalry Al Unser Jr.'s Road to the Top Aladdin Alien 3 Alien vs. Predator American Gladiators An American Tail : Fievel Goes West Andre Agassi Tennis Animaniacs Arcade's Greatest Hits : The Atari Collection 1 Arcana Ardy Lightfoot Arkanoid : Doh It Again Art of Fighting Axelay B.O.B. Ballz 3D : Fighting at Its Ballziest Barbie Super Model Barkley Shut Up and Jam! Bass Masters Classic Bass Masters Classic : Pro Edition Bassin's Black Bass Batman Forever Batman Returns Battle Blaze Battle Cars Battle Clash Battle Grand Prix Battletoads & Double Dragon Battletoads in Battlemaniacs Bazooka Blitzkrieg Beauty and the Beast Beavis and Butt-Head Bebe's Kids Beethoven : The Ultimate Canine Caper! Best of the Best : Championship Karate Big Sky Trooper Biker Mice from Mars Bill Laimbeer's Combat Basketball Bill Walsh College Football BioMetal Blackthorne BlaZeon : The Bio-Cyborg Challenge Bonkers Boogerman : A Pick and Flick Adventure Boxing Legends of the Ring Brain Lord Bram Stoker's Dracula Brandish Brawl Brothers BreakThru! Breath of Fire Breath of Fire II Brett Hull Hockey Brett Hull Hockey 95 Bronkie the Bronchiasaurus Brunswick World Tournament of Champions Brutal : Paws of Fury Bubsy II Bubsy in : Claws Encounters of the Furred Kind Bugs Bunny : Rabbit Rampage Bulls vs Blazers and the NBA Playoffs Bust-A-Move Cacoma Knight in Bizyland Cal Ripken Jr. -

National Videogame Museum Fact Sheet

National Videogame Museum Fact Sheet Overview The National Videogame Museum (NVM) is the only museum in America dedicated to the history of the videogame industry. The museum provides a physical location that interactively displays the history and impact on popular culture that videogames have had on the public. The museum features more than 100,000 videogame consoles, games, artifacts and more than 25 years of historical documents and data archives. NVM is an established 501(c)(3) non-profit and was founded by John Hardie, Sean Kelly and Joe Santulli. The founders have collected videogame artifacts and other materials since the 1980s and have spent the past 20 years tracking-down the pioneers of the videogame industry to document their innovations and contributions. Also during that time, they have been building historical videogame exhibits at all of the major industry events and have come to be known as the foremost historians of videogame history. Together, they formed the Videogame History Museum in 2009 and set out to find a permanent home. In September 2014, The City of Frisco voted unanimously to build out the unfinished area in the Frisco Discovery Center and allow it to be the new home of the National Videogame Museum. The family-friendly museum serves as a trip down memory lane for people of all ages who grew up playing videogames well as those who are interested in a deeper understand of the origins of the industry. Mascot Blip!, the official mascot of the National Videogame Museum, is created from a variety of videogame components including joysticks, arcade buttons, cables and plugs. -

Ne Castles Ith Familiar Brics Balancing Copyrights

337 NE! CASTLES !ITH FAMILIAR BRIC"S ! BALANCING COPYRIGHTS# SPIRITUAL SUCCESSOR VIDEO GAMES# AND COMPETITION BY NATHANIEL NG $ This paper reviews intellectual property and non- competition implications that arise from the recent trend within the video game industry of veteran game developers leaving their longtime publishers and creating new IP. This paper provides examples of this trend with the departures of game developers from well-known video game franchises like Mega Man, Castlevania, and Banjo-Kazooie, who go on to make so-!"##$% &'()*)+,"# ',!!$''-* .)%$- /"0$'1 +2"+ are not explicitly sequels buthavesomenotable similarities to their prior work. These departures are reminiscent of the departures of four high profile programmers from Atari in the 34567' +- 8-*0 9!+).)')-:; In the Atari-Activision situation, Atari used intellectual property-based causes of action to hinder these departed programmers from competing in the software market. This paper examines the possibilities and implications if such tactics would be used against game developers today by performing copyright analyses on '$.$*"# -8 +2$'$ &'()*)+,"# ',!!$''-* .)%$- /"0$'1 ): comparison to their respective predecessors. By allowing other video game companies to produce work that has some similarities allowable within copyright law but hinder a former employee from also doing so by merely threatening legal action resembles the specter of a non-compete agreement, but without its traditional limitations. The paper then goes on to discuss why abusing intellectual property law to effectively enforce a covenant not to compete when Volume 58 ! Number 3 338 IDEA ! The Journal of the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property one did not exist or would not be valid would weaken intellectual property rights and lead to market failures. -

SNES Inventory

SNES inventory Stock Number Name Category Condition Price Quantity Notes 0058-000000213119 Metal Combat Super Nintendo Loose $4.99 1 0058-000000213121 Super Play Action Football Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213122 Chessmaster Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213126 Natsume Championship Wrestling Super Nintendo Loose $11.99 1 0058-000000213127 Super Tennis Super Nintendo Loose $4.99 1 Bad Label 0058-000000213150 ABC Monday Night Football Super Nintendo Loose $4.99 1 0058-000000213153 NHL Stanley Cup Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213154 NBA Showdown Super Nintendo Loose $4.99 1 0058-000000213157 Hal's Hole in One Golf Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213161 Hal's Hole in One Golf Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213163 Super Play Action Football Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213200 NHL 95 Super Nintendo Loose $4.99 1 0058-000000213202 Smartball Super Nintendo Loose $7.99 1 0058-000000213205 Stunt Race FX Super Nintendo Loose $9.99 1 0058-000000213206 Super Tennis Super Nintendo Loose $5.99 1 0058-000000213208 NHL Stanley Cup Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213209 NHLPA Hockey '93 Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213211 Super Black Bass Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213219 NFL Quarterback Club Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213221 Pro Quarterback Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213222 Super High Impact Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 1 0058-000000213223 NBA Showdown Super Nintendo Loose $4.99 1 0058-000000213232 NCAA Basketball Super Nintendo Loose $3.99 -

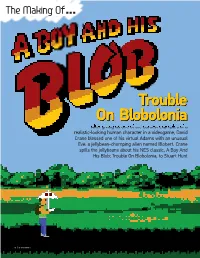

Trouble on Blobolonia

The Making Of Trouble On Blobolonia A er giving us one of the earliest examples of a realistic-looking human character in a videogame, David Crane blessed one of his virtual Adams with an unusual Eve: a jellybean-chomping alien named Blobert. Crane spills the jellybeans about his NES classic, A Boy And His Blob: Trouble On Blobolonia, to Stuart Hunt 70 | RETRO GAMER 070-73 RG77 Aboyandhisblob.indd 70 10/5/10 18:59:54 THE MAKING OF: A BOY AND HIS BLOB: TROUBLE ON BLOBOLONIA orging a relationship inside a game has the power to inspire emotion like nothing else. Rarely is a strong bond Fbetween the gamer and their avatar struck up over the course of an adventure. How can it? The instant our virtual hero dies our natural reaction is to lambast their idiocy for making us replay something over again, and the second that they do achieve something amazing it’s ourselves that we’re mentally giving last adventure, Pitfall II: Lost Caverns, a pat on the back to. Alone, Boy and Blob were useless. in 1983. Working alongside his friend Throw another character into the mix, and collaborator Garry Kitchen, and though – a character that is looking to publishing the game under their new you for direction and guidance – and Together they were unstoppable studio Absolute Entertainment, Crane things can change dramatically. Who saw an opportunity to do something can forget frantically trying to prevent Blob. Released exclusively for the NES, truly unique in the genre. their stranded party from being carried the game saw a young boy befriend an “As you might guess from Pitfall, away by pterodactyls in Denton Designs’ intergalactic white ball of glob that had I like adventure games with puzzles 8-bit classic Where Time Stood Still, or a peculiar reaction to sugary jellybeans.