Erich Neumann: Theorist of the Great Mother

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presidential Documents Vol

57663 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 85, No. 179 Tuesday, September 15, 2020 Title 3— Proclamation 10070 of September 3, 2020 The President National Days of Prayer and Remembrance, 2020 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation During these National Days of Prayer and Remembrance, we pay tribute to the nearly 3,000 precious lives lost on September 11, 2001. We solemnly honor them and pray that those who bear the burdens of unimaginable loss find comfort in knowing that God is close to the brokenhearted and that He provides abiding peace. The memories of that fateful morning still touch American hearts and remind us of our Nation’s reliance on Almighty God. When cowardly terrorists attacked our homeland, we witnessed the unthinkable as each successive plane struck the very heart of our Nation. As the Twin Towers fell and the Pentagon was hit, the peace and calm in the lives of innocent families were shattered. Our Nation watched in shock as courageous first responders faced great peril to save the lives of their fellow Americans. Onboard United Flight 93, a group of heroic individuals braced themselves to stop hijackers from hitting our Nation’s Capital. Passenger Todd Beamer told Lisa Jefferson, a call center supervisor in Chicago who stayed on the phone with him until the end, that he would ‘‘go out on faith’’ and asked her to recite the Lord’s Prayer with him over the phone, beginning: ‘‘Our Father, who art in heaven.’’ Despite immeasurable loss, we were not defeated. Our Nation’s darkest hour was pierced by candlelight, our anguish was met with prayer, and our grief was met with unity. -

Ave Developed a General Understanding That the Origins of Sports Activitieslie Rooted in the Cults of Antiquity

ge. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 129 827 SP 010 544 AUTHOR Eisen, George TITLE The Role of Women in Ancient Fertility Cults andthe Origin of Sports. PUB DATE Jun 76 NOTE 11p.; Paper presented to the Annual Conventionof North American Society for Sport History (4th, Eugene, Oregon, June 16-19, 1976) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$1.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ancient History; *Athletics; Dance; *Mythology; *Religious Factors; Social History; Wouens Athletics; *Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS Agricultural Cults; *Fertility Cults; Sport History ABSTRACT Sports historians have developed a general understanding that the origins of sports activitieslie rooted in the cults of antiquity. More specifically, it can be seenthat ancient religious customs and festivals in honor of fertilitygoddesses were transformed into sports activities in which womenfigured prominently. Throughout the Mediterranean basin, cultsof the Earth Mother (Magna Mater, Gain, Isis, Demeter) wereclosely associated with fertility and agriculture. Festivals heldin honor of these goddesses involved singing, acrobatic dancing,and racing. Women, as devotees of these deities, were the majorparticipants in bare-foot fertility races, ball games, and cult rituals,which later developed into nonreligious folk games. It wouldthus seem that women's contributions to the development of sports and games were more important than previously acknowledged by scholars. (NB) *********************************************************************** * Documents acquired by ERIC include manyinformal unpublished * * materials not available-from othersources.,ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain-tte-best copyavailable:,Neverthelesm..iteisof murginal * * reproducibility are.often encounterdd andthistffectsc,tthe quality .*'. * of the:microfiche andhardcopy'reproductionstEiIUkei'-available_ * * via the:ERIC Document Reproduction-Service'.1EDR$W:168S%is not * responsible for the-quality ofthe:originak:do00entReproductions:, * supplfed by EDRS-are the .best-that canbelaide2ficin'the,original.;_. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed. -

Bollingen Series, –

Bollingen Series, – Bollingen Series, named for the small village in Switzerland where Carl Gustav Jung had a private retreat, was originated by the phi- lanthropist Paul Mellon and his first wife, Mary Conover Mellon, in . Both Mellons were analysands of Jung in Switzerland in the s and had been welcomed into his personal circle, which included the eclectic group of scholars who had recently inaugu- rated the prestigious conferences known as the Eranos Lectures, held annually in Ascona, Switzerland. In the couple established Bollingen Foundation as a source of fellowships and subventions related to humanistic scholarship and institutions, but its grounding mission came to be the Bollin- gen book series. The original inspiration for the series had been Mary Mellon’s wish to publish a comprehensive English-language translation of the works of Jung. In Paul Mellon’s words,“The idea of the Collected Works of Jung might be considered the central core, the binding factor, not only of the Foundation’s general direction but also of the intellectual temper of Bollingen Series as a whole.” In his famous Bollingen Tower, Jung pursued studies in the reli- gions and cultures of the world (both ancient and modern), sym- bolism, mysticism, the occult (especially alchemy), and, of course, psychology. The breadth of Jung’s interests allowed the Bollingen editors to attract scholars, artists, and poets from among the brightest lights in midcentury Europe and America, whether or not their work was “Jungian” in orientation. In the end, the series was remarkably eclectic and wide-ranging, with fewer than half of its titles written by Jung or his followers. -

Chthonic Aspects of Macdonald's Phantastes: from the Rising of The

Chthonic Aspects of MacDonald’s Phantastes: From the Rising of the Goddess to the Anodos of Anodos Fernando Soto The Herios was a woman’s festival. Plutarch of course could not be present at the secret ceremonies of the Thyaiades, but his friend Thyia, their president, would tell him all a man might know . From the rites known to him he promptly conjectured that it was a “Bringing up of Semele.” Semele, it is acknowledged, is but a Thraco-Phrygian form of Gaia, The “Bringing up of Semele” is but the Anodos of Gala or of Kore the Earth Maiden. It is the Return of the vegetation or Year-Spirit in the spring. (Jane Harrison, Themis 416) 1. Introduction and General Backgrounds hantastes is one of the most mysterious books George MacDonald wrote andP one of the least understood books in the English tradition. Since its publication in 1858, reviewers, readers and researchers have experienced great difficulties understanding the meaning of this complex work.The perceived impediments have been so great that some scholars remain unsure whether Phantastes contains a coherent plot or structure (Reis 87, 89, 93-94; Robb 85, 97; etc.). Other critics appear adamant that it contains neither (Wolff 50; Manlove, Modern 55, 71, 77, 79; England 65, 93, 122). Even those scholars who sense a structure or perceive a plot differ not only regarding the types of structure(s) and/or plot(s) they acknowledge (Docherty 17-22; McGillis “Community” 51-63; Gunther “First Two” 32-42), but in deciding into what, if any, genres or traditions Phantastes belongs (Prickett, “Bildungsroman” 109-23; Docherty 19, 23, 30, McGillis, “Femininity” 31-45; etc.). -

HEROES Witness of the Saints and Martyrs, Purpose of Sacrifice and Suffering LIFE NIGHT OUTLINE

HEROES Witness of the Saints and Martyrs, Purpose of Sacrifice and Suffering LIFE NIGHT OUTLINE Goal for the Life Night GATHER 15 Minutes The goal of this night is for teens to understand the role of the saints and martyrs as holy examples of living Superpowers and powerful intercessors. This night will help them to As the teens enter the room, have small pieces of paper understand why suffering, sacrifice and even death is an and pens at a table. Ask each teen to write down the important part of the lives of the saints. Finally, this night craziest superpower they can think of (as long as it is will show how each teen is called to sainthood. appropriate, of course). Some examples could be “makes anyone they look at fall asleep” or “changes everything Life Night at a Glance they touch into chocolate” or “invisible to animals” - the crazier, the better. Have the teens put their superpowers Based on the popular TV show “Heroes” this night looks at into a basket. Then have each teen write their name on the how the heroes of our faith, the saints and martyrs, are a different slip of paper and put their names in a different ordinary people who have accepted the extraordinary call basket. of following Christ. The night begins with crazy improv skits performed by the teens. The teaching will show how the witness of the saints and martyrs shows us what true Welcome and Introductions (5 min) heroism looks like. After the teaching, the teens will get The youth minister brings the group together and the opportunity to choose a saint they want to learn more welcomes everyone to the Life Night. -

DADS and HEROES Fathers Day 2013

DDAADDSS && HHEERROOEESS INTERGENERATIONAL WORSHIP FOR FATHERS DAY CONTENTS USING THIS WORSHIP RESOURCE All Age Worship Notes These notes have been prepared by the What it is ........................................................... 2 Children and Family Ministry Team of Mission Planning ............................................................ 2 Resourcing SA to help congregations plan Invitation and advertising ............................. 2 worship that involves children and families as well Hospitality ......................................................... 3 as youth, young adults, middle-aged and older people. Worship space ................................................. 3 Visuals ............................................................... 3 You may make as many copies of the notes as Music ................................................................. 3 needed for your worship planners and leaders. Movement ....................................................... 4 The use of music and other copyright elements is not covered in this permission. Relationships .................................................... 4 Science and mathematics ........................... 4 Read through all the material. Discuss it as a Something to take home .............................. 4 planning team. You may use any of the ideas Worship leaders ............................................... 4 that are appropriate in your situation. Sermon .............................................................. 4 Bible quotations, unless otherwise -

Appendices 1 – 12

APPENDICES 1 – 12 Religion Course of Study PreK-12 --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 Appendix 1: God’s Plan of Salvation -- A Summary (Used with permission, Diocese of Green Bay, WI) It is very important that before we dive into the religion Course of Study each year, we set the stage with an overview of God’s plan of salvation – the adventurous story of God’s unfailing love for us, his persistence in drawing us back to himself, and the characters along the way who succeed and fail in their quest for holiness. The context of the Story of Salvation will provide the proper foundation for the rest of your catechetical instruction. The Story can be taught as a one-day lesson, or a week long lesson. Each teacher must make a determination of how long they will take to present the Story to their students. It is important that the story be presented so that each of us can understand our place and purpose in the larger plan of God, as well as how the Church is central to God’s plan of salvation for the world. An overview of God’s plan is to be presented at the beginning of each year, and should be revisited periodically during the year as the subject matter or liturgical season warrants. Please make the presentation appropriate to the grade level. 1. God is a communion of Persons: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. The three Persons in one God is the Blessed Trinity. God has no beginning and no end. -

EXPLORING the CHARACTERIZATION of SHAKESPEARE's VILLAINS by Olawunmi Amusa BA

EXPLORING THE CHARACTERIZATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S VILLAINS by Olawunmi Amusa B.A (Eastern Mediterranean University) 2015 Submitted in partial satisfaction for the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS in HUMANITIES in the GRADUATE SCHOOL of HOOD COLLEGE Accepted: ----------------------- -------------------------- Terry Scott, PhD. Corey Campion Committee Member Program Director ---------------------- Didier Course, PhD ------------------------ Committee Member April Boulton, PhD Dean of the Graduate School ------------------------- Heather Mitchell-Buck, PhD Portfolio Advisor ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION--------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 CHAPTER ONE: LANGUAGE USED BY FOUR OF SHAKESPEARE’S VILLAINS-------- 11 CHAPTER TWO: INCLUDING A COMIC THEME TO A TRAGEDY: THE CASE OF SCOTLAND, PA-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 31 CHAPTER THREE: DUAL REPRESENTATION OF PROSPERO’S EPILOGUE------------- 44 BIBLIOGRAPHY------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 58 1 Introduction When we watch a movie or read a book, we tend to watch out for the hero or villain. For those of us who grew up in the Disney era, we have been trained to watch out for good and evil, with the belief that the heroes will come to save us. Despite anything that happens, we always know that the heroes will always win, and the villain will fail. However, a story does not seem to be complete without the villains. If the heroes do not have any villain to fight, then how do we define their acts as being heroic? Villains provide a conflict that intrigues the audience as well as readers because it gives the heroes conflict and something to look forward to. Without the conflict of the villains, there will be not much to the backstory of the heroes. Therefore, villains are a great addition to the success of a piece of work. -

In the Media, a Woman's Place

Symposium In the Media, A Woman's Place OR WOMEN AND THE MEDIA, 1992 was a year of sometimes painful change-the aftermath of the Anita Hill PClarence Thomas hearings; the public spectacle of a vice presi dent's squabble with a fictional TV character; Hillary Rodham Clinton's attempt to redefine the role of the political wife; election of women to Congress and to state offices in unprecedented numbers. Whether the "Year of the Woman" was just glib media hype or truly represented a sea change for women likely will remain subject to debate for years to come. It is undeniable, however, that questions of gender and media performance became tightly interwoven, perhaps inextricably, in 1992. What do the developments of 1992 portend for media and women? What lessons should the media have learned? What changes can be predicted? We invited 15 women and men from both inside and outside the media for their views on those and related issues affecting the state of the media and women in 1993 and beyond. The result is a kind of sy~posium of praise, warnings and criticism for the press from jour nahsts and news sources alike, reflecting on changes in ' media treat ment of women, and in what changes women themselves have wrought on the press and the society. LINDA ELLERBEE Three women have forced people to rethink their attitudes toward women and, perhaps more importantly, caused women to rethink 49 Symposium-In the Media, A Womans how we see ourselves. Two of those women-Anita Hill and Clinton-are real. -

We Belong to Him Galatians 4; Ephesians 1-2

Brian Fisher Grace Bible Church We Belong to Him Galatians 4; Ephesians 1-2 God our Father turned His face away from the Only Begotten, so that we, children of sin, wrath and death, could be adopted into the family of God. Praise God! We belong to Him! Need for belonging • Ladies, there are other ways that you experienced rejection or belonging growing up, but for guys it was choosing teams on the playground. • Stressful time. Reoccurred every day. o Established your value as a human being for that day o Asked my kids; who would you pick? Depends on the contest? Math, science, history, soccer, basketball? Always pick those who can perform the best. Depending on how badly you want to win, you might even skip over your friends. Playground is a cutthroat world! • We all want to belong. We all need to belong. And we want to know that there is a valuable contribution we can make. The most fundamental way that God has revealed Himself is as a Trinity: Father, Son and Spirit, enjoying one another, loving one another for all of eternity. Creating in order to share that love, to invite us into that love at the initiation of the Father. What does a great father do? A great father creates a great family. In a great family... • You belong (group). And this is a group worth belonging to • You are special (individual) o No matter how many children are in the family, within this special group, you have a special place; unique contribution only you can make • God, our Father, has done this for you. -

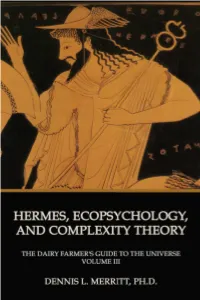

Hermes, Ecopsychology, and Complexity Theory

PSYCHOLOGY / JUNGIAN / ECOPSYCHOLOGY “Man today is painfully aware of the fact that neither his great religions nor his various philosophies seem to provide him with those powerful ideas that would give him the certainty and security he needs in face of the present condition of the world.” —C.G. Jung An exegesis of the myth of Hermes stealing Apollo’s cattle and the story of Hephaestus trapping Aphrodite and Ares in the act are used in The Dairy Farmer’s Guide to the Universe Volume III to set a mythic foundation for Jungian ecopsychology. Hermes, Ecopsychology, and Complexity Theory HERMES, ECOPSYCHOLOGY, AND illustrates Hermes as the archetypal link to our bodies, sexuality, the phallus, the feminine, and the earth. Hermes’ wand is presented as a symbol for COMPLEXITY THEORY ecopsychology. The appendices of this volume develop the argument for the application of complexity theory to key Jungian concepts, displacing classical Jungian constructs problematic to the scientific and academic community. Hermes is described as the god of complexity theory. The front cover is taken from an original photograph by the author of an ancient vase painting depicting Hermes and his wand. DENNIS L. MERRITT, Ph.D., is a Jungian psychoanalyst and ecopsychologist in private practice in Madison and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A Diplomate of the C.G. Jung Institute of Analytical Psychology, Zurich, Switzerland, he also holds the following degrees: M.A. Humanistic Psychology-Clinical, Sonoma State University, California, Ph.D. Insect Pathology, University of California- Berkeley, M.S. and B.S. in Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison. He has participated in Lakota Sioux ceremonies for over twenty-five years which have strongly influenced his worldview.