Alvand Construction, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100Th Anniversary Dematteis Organizaion – Construction Today

FOCUS PROUD HISTORY The DeMatteis Organization celebrates 100 years of developing and building. BY ALAN DORICH The DeMa eis Organization/ Leon D. DeMa eis He initially specialized in renovation projects as well as the Construction Corp. construction of factory lofts and warehouses at Bush Terminal, a www.dema eisorg.com waterfront shipping, warehousing and manufacturing complex • Headquarters: Elmont, N.Y. also located in Brooklyn and now known as Industry City. In the • Employees: 100 1930s, DeMatteis supported residential and business growth in “We are a family-like group of the borough by building and renovating shops, offices and apart- people here who love what ey ment buildings. do as ey dive into each and Growing Its Legacy every project.” The second generation of DeMatteis family involvement began in – Sco DeMa eis, principal and COO the company when Leon DeMatteis’ son, Fred, joined in the 1940s. ome companies choose to have THE DEMATTEIS ORGANIZATION/LDDCC THE DEMATTEIS only one specialty, but for the past century, The DeMatteis Organiza- tion has thrived by having several. SNot only does the Elmont, N.Y.-based company practice real estate development and property management, “but we’re also a builder at heart,” Principal and COO Scott DeMatteis declares. When The DeMatteis Organization de- COVER COVER STORY: velops a project, it is built through Leon D. DeMatteis Construction Corp. (LDDCC), its » Richard (clockwise from above), Alex, Michael and Scott DeMatteis continue their construction affi liate. This pleases its part- family’s legacy as a top New York builder and developer. ners, who “are comforted that we’re going to control the project through both of the entities,” he says. -

2017 Prevailing Wage Rates Lincoln County

2017 PREVAILING WAGE RATES LINCOLN COUNTY DATE OF DETERMINATION: October 1, 2015 APPLICABLE FOR PUBLIC WORKS PROJECTS BID/AWARDED OCTOBER 1, 2016 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 30, 2017* *Pursuant to NAC 338.040(3), "After a contract has been awarded, the prevailing rates of wages in effect at the time of the opening of bids remain in effect for the duration of the project." As Amendments/Addenda are made to the wage rates, such will be posted to sites of the respective counties. Please review regularly for any amendments posted or contact our offices directly for further assistance with any amendments to the rates. AIR BALANCE TECHNICIAN ALARM INSTALLER BOILERMAKER BRICKLAYER CARPENTER CEMENT MASON ELECTRICIAN-COMMUNICATION TECH. ELECTRICIAN-LINE ELECTRICIAN-NEON SIGN ELECTRICIAN-WIREMAN ELEVATOR CONSTRUCTOR FENCE ERECTOR FLAGPERSON FLOOR COVERER GLAZIER HIGHWAY STRIPER HOD CARRIER-BRICK MASON HOD CARRIER-PLASTERER TENDER IRON WORKER LABORER MECHANICAL INSULATOR MILLWRIGHT 2016-2017 Prevailing Wage Rates – Lincoln County 1 OPERATING ENGINEER OPERATING ENG. STEEL FABRICATOR/ERECTOR OPERATING ENGINEER-PILEDRIVER PAINTER PILEDRIVER (NON-EQUIPMENT) PLASTERER PLUMBER/PIPEFITTER REFRIGERATION ROOFER (Does not include sheet metal roofs) SHEET METAL WORKER SPRINKLER FITTER SURVEYOR (NON-LICENSED) TAPER TILE /TERRAZZO WORKER/MARBLE MASON TRAFFIC BARRIER ERECTOR TRUCK DRIVER WELL DRILLER LUBRICATION AND SERVICE ENGINEER (MOBILE AND GREASE RACK) SOIL TESTER (CERTIFIED) SOILS AND MATERIALS TESTER PREVAILING WAGE RATES INCLUDE THE BASE RATE AS WELL AS ALL APPLICABLE FRINGES NRS 338.010(21) “Wages” means: (a) The basic hourly rate of pay; and (b) The amount of pension, health and welfare, vacation and holiday pay, the cost of apprenticeship training or other similar programs or other bona fide fringe benefits which are a benefit to the workman. -

Prevailing Wage Rates for Cook County Effective Sept. 1, 2017

Prevailing Wage rates for Cook County effective Sept. 1, 2017 Trade Title Region Type Class Base Fore- M-F OSA OSH H/W Pension Vacation Training Wage man OT Wage ASBESTOS ABT-GEN ALL ALL 41.20 42.20 1.5 1.5 2 14.65 12.32 0.00 0.50 ASBESTOS ABT-MEC ALL BLD 37.46 39.96 1.5 1.5 2 11.62 11.06 0.00 0.72 BOILERMAKER ALL BLD 48.49 52.86 2 2 2 6.97 19.61 0.00 0.90 BRICK MASON ALL BLD 45.38 49.92 1.5 1.5 2 10.45 16.68 0.00 0.90 CARPENTER ALL ALL 46.35 48.35 1.5 1.5 2 11.79 18.87 0.00 0.63 CEMENT MASON ALL ALL 44.25 46.25 2 1.5 2 14.00 17.16 0.00 0.92 CERAMIC TILE FNSHER ALL BLD 38.56 38.56 1.5 1.5 2 10.65 11.18 0.00 0.68 COMM. ELECT. ALL BLD 43.10 45.90 1.5 1.5 2 8.88 13.22 1.00 0.85 ELECTRIC PWR EQMT OP ALL ALL 50.50 55.50 1.5 1.5 2 11.69 16.69 0.00 3.12 ELECTRIC PWR GRNDMAN ALL ALL 39.39 55.50 1.5 1.5 2 9.12 13.02 0.00 2.43 ELECTRIC PWR LINEMAN ALL ALL 50.50 55.50 1.5 1.5 2 11.69 16.69 0.00 3.12 ELECTRICIAN ALL ALL 47.40 50.40 1.5 1.5 2 14.33 16.10 1.00 1.18 ELEVATOR CONSTRUCTOR ALL BLD 51.94 58.43 2 2 2 14.43 14.96 4.16 0.90 FENCE ERECTOR ALL ALL 39.58 41.58 1.5 1.5 2 13.40 13.90 0.00 0.40 GLAZIER ALL BLD 42.45 43.95 1.5 1.5 2 14.04 20.14 0.00 0.94 HT/FROST INSULATOR ALL BLD 50.50 53.00 1.5 1.5 2 12.12 12.96 0.00 0.72 IRON WORKER ALL ALL 47.33 49.33 2 2 2 14.15 22.39 0.00 0.35 LABORER ALL ALL 41.20 41.95 1.5 1.5 2 14.65 12.32 0.00 0.50 LATHER ALL ALL 46.35 48.35 1.5 1.5 2 11.79 18.87 0.00 0.63 MACHINIST ALL BLD 47.56 50.06 1.5 1.5 2 7.05 8.95 1.85 1.47 MARBLE FINISHERS ALL ALL 33.95 33.95 1.5 1.5 2 10.45 15.52 0.00 0.47 MARBLE MASON ALL BLD -

Prevailing Wage Rates System Annual Adjusted July 1St Rates

Details of Prevailing Wage Rates by Town Page 1 of7 Prevailing Wage Rates System Annual Adjusted July 1st Rates I>.9L WeJLSite 0 Wag!Lal1.d_W-9rkpJ~ce-.issuJ!_~0 Wage Rate~ 0 Building Rates - Hartford Building Rates - Hartford (effective July 1, 2009) Classification Hourly Rate Benefits 1a) Asbestos Worker/Insulator (Includes application of insulating materials, protective coverings, coatings, & finishes to all types of mechanical systems; application of firestopping material for wall openings & $34.21 19.81 penetrations in walls, floors, ceilings - Last updated 9/1/08 1b) AsbestosjToxic Waste Removal Laborers: Asbestos removal and encapsulation (except its removal from mechanical systems which are not to be scrapped), toxic waste removers, blasters. **See Laborers Group 7** 2) Boilermaker $33.79 34%19.48+16.9819.1214.788.96+ a 3a) Bricklayer, Cement Mason, Concrete Finisher (including caulking), Plasterers, Stone Masons$30.91$24.90$30.78$32.10 3b) Tile Setter 3c) Terrazzo Workers, Marble Setters - Last updated 10/1/08 3d) Tile, Marble & Terrazzo Finishers http://www2.ctdo1.state.ct.us/W ageRates Web/W ageRatesbyTown.aspx?Town= Hartford 10/13/2009 Details of Prevailing Wage Rates by Town Page 2 ot7 3e) Plasterer $32.10 19.48 ------LABORERS------ 4) Group 1: Laborers (common or general), carpenter tenders, wrecking laborers, fire watchers. $24.25 14.45 4a) Group 2: Mortar mixers, plaster tender, power buggy operators, powdermen, $24.50 14.45 fireproofer/mixer/nozzleman, fence erector. 4b) Group 3: Jackhammer operators, mason tender (brick) -

State of Wisconsin Classification Specification

Effective Date: September 1983 Modified Effective: May 14, 2006 STATE OF WISCONSIN CLASSIFICATION SPECIFICATION CRAFTSWORKER-LEAD I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose of This Classification Specification This classification specification is the basic authority under ER 2.04, Wis. Adm. Code, for making classification decisions relative to present and future skilled trade positions located within state government that also function as lead worker to other skilled trade positions. This classification specification will not specifically identify every eventuality or combination of duties and responsibilities of positions that currently exist, or those that result from changing program emphasis in the future. Rather, it is designed to serve as a framework for classification decision-making in this occupational area. Classification decisions must be based on the “best fit” of the duties within the existing classification structure. The “best fit” is determined by the majority (i.e., more than 50%) of the work assigned to and performed by the position when compared to the class concepts and definition of this specification or through other methods of position analysis. Position analysis defines the nature and character of the work through the use of any or all of the following: definition statements; listing of areas of specialization; representative examples of work performed; allocation patterns of representative positions; job evaluation guide charts, standards or factors; statements of inclusion and exclusion; licensure or certification requirements; and other such information necessary to facilitate the assignment of positions to the appropriate classification. B. Inclusions This classification is to be used exclusively for positions performing the full range of journey level trades work within a specialized craft and functioning as lead worker to other journey level trades work positions within that same specialized craft for a majority of the time. -

Federal Wage System Job Grading Standard for Plastering, 3605

Plastering, 3605 TS-9 November 1969 Federal Wage System Job Grading Standard For Plastering, 3605 Table of Contents WORK COVERED ........................................................................................................................................ 2 TITLES .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 GRADE LEVELS .......................................................................................................................................... 2 HELPER AND INTERMEDIATE JOBS ........................................................................................................ 2 PLASTERER, GRADE 9 .......................................................................................................................... 2 U.S. Office of Personnel Management 1 Plastering, 3605 TS-9 November 1969 WORK COVERED This standard is used to grade all nonsupervisory jobs involved in the application and finishing of plaster surfaces in the construction and repair of interior walls and ceilings and stucco exterior walls. TITLES Jobs covered by this standard are to the titled Plasterer. GRADE LEVELS This standard does not describe all possible levels at which jobs might be established. If jobs differ substantially from the skill, knowledge, and other work requirements described in the grade level of the standard, they may warrant grading either above or below that grade. HELPER AND INTERMEDIATE JOBS Helper and intermediate -

Scope of Work Provisions for Drywall Installer/Lather (Carpenter) in San Diego County

STATE OF CALIFORNIA EDMUND G. BROWN JR., Governor DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS Office of the Director - Research Unit MAILING ADDRESS: 455 Golden Gate Avenue, 9th Floor P. O. Box 420603 San Francisco, CA 94102 San Francisco, CA 94142-0603 SCOPE OF WORK PROVISIONS FOR DRYWALL INSTALLER/LATHER (CARPENTER) IN SAN DIEGO COUNTY SD-31-X-41 31-X-41 MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN SOUTHWEST REGIONAL COUNCIL OF CARPENTERS and the WESTERN WALL AND CEILING CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION, INC. 2012 - 2016 DRYWALL MASTER AGREEMENT The Southwest Regional Council of Carpenters and the Western Wall and Ceiling Contractors Association, Inc. agree to modify and amend the Southern California Drywall/Lathing Master Agreement dated July 1,2006,as extended, as follows: SWRCC/WWCCA July 1, 2012 1 7. Amend Article XXIII to provide for a new four (4) year agreement extending through June 30,2016. Change dates throughout Agreement. 8. Language contained in MOUs executed by the parties during the term of the previous Agreement, such as the definition of Stocker/Scrapper and the Wet Wall Apprenticeship will be incorporated into the body of the Master Agreement. Effective date July 1,2012. Dated : WESTERN WALL AND CEILING SOUTHWEST REGIONAL COUNCIL CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION OF CARPENTERS Ian Hendry Mike McCarron CEO Executive Secretary Treasurer June 28,2012, version 2 SWRCC/WWCCA July 1,2012 2 31-X-41 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA DRYWALL / LATHING MASTER AGREEMENT between DRYWALL I LATHING CONFERENCE of the WESTERN WALL & CEILING CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION, INC. and the SOUTHWEST REGIONAL COUNCIL OF CARPENTERS of the UNITED BROTHERHOOD OF CARPENTERS AND JOINERS OF AMERICA JULY 1, 2006 TO JUNE 30, 2010 ARTICLE I employees of the Contractor. -

Mason-Plasterer

MICHIGAN CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION JOB SPECIFICATION MASON-PLASTERER JOB DESCRIPTION Employees in this job participate in and oversee the construction, maintenance, and repair of brick, cement, stone, and plaster for buildings, bridges, roads, or other structures. There are three classifications in this job. Position Code Title – Mason-Plasterer-E Mason-Plasterer 8 This is the intermediate level. The employee performs mason/plasterer assignments while learning and developing skills under the guidance of a higher-level Mason- Plasterer. Mason-Plasterer E9 This is the experienced level. The employee performs a full range of mason/plasterer assignments using independent judgement to make decisions requiring the application of procedures and practices to specific work situations. Position Code Title – Mason-Plasterer-A Mason-Plasterer 10 This is the advanced level. The employee functions as a crew leader, overseeing the work of lower-level Mason-Plasters, prisoner crews, or others and performs experienced-level assignments. NOTE: Employees generally progress through this series to the experienced level based on satisfactory performance and possession of the required experience. JOB DUTIES NOTE: The job duties listed are typical examples of the work performed by positions in this job classification. Not all duties assigned to every position are included, nor is it expected that all positions will be assigned every duty. Constructs, repairs or demolishes concrete bases, walls, floors, chimneys, sidewalks, and roadways by using electric rotary hammers, air hammers, masonry saws, and other hand and power tools of the trade. MASON-PLASTERER PAGE NO. 2 Installs, repairs, and replaces ceilings, tiles, floor tiles, and exterior roofing. Prepares surface with hand and power sanders and buffers before spreading paste on surface. -

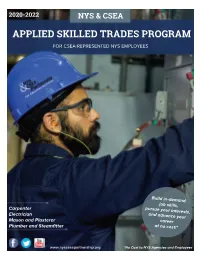

2020-2022 Nys & Csea Applied Skilled Trades Program for Csea-Represented Nys Employees

2020-2022 NYS & CSEA APPLIED SKILLED TRADES PROGRAM FOR CSEA-REPRESENTED NYS EMPLOYEES Build in-demand job skills, Carpenter pursue your interests, Electrician and advance your Mason and Plasterer career Plumber and Steamfitter at no cost!* www.nyscseapartnership.org *No Cost to NYS Agencies and Employees Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 Participant Eligibility .............................................................1 How Agencies and Facilities Apply - Important Deadlines ...............................................................2 Selection Process .....................................................................2 No Cost to Agencies and Employees .................................2 Required Coursework .............................................................2 Refresher and Core Courses ..................................................3 Carpenter - Trade Courses ....................................................4 Electrician - Trade Courses ..................................................5 Mason and Plasterer - Trade Courses ...............................6 Plumber and Steamfitter - Trade Courses ........................7 Overview of Applied Skilled Trades Program Introduction The NYS & CSEA Applied Skilled Trades Program (ASTP) provides CSEA-represented NYS employees with two years of trade theory instruction. This instruction meets the relevant coursework component of the minimum qualifications for appointment to four non-competitive -

REVITALISING the DIMINISHED CRAFT of SOLID PLASTERING an International Specialised Skills Institute Fellowship

REVITALISING THE DIMINISHED CRAFT OF SOLID PLASTERING An International Specialised Skills Institute Fellowship. BRIAN MAXWELL Sponsored by The Perpetual Foundation / Eddy Dunn International Fellowship 2016 © Copyright February 2020 REVITALISING THE DIMINISHED CRAFT OF SOLID PLASTERING TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Executive Summary 2 3. Fellowship Background 5 4. Fellowship Learnings 19 5. Personal, Professional and Sectoral Impact 20 6. Recommendations and Considerations 22 7. References 23 REVITALISING THE DIMINISHED CRAFT OF SOLID PLASTERING 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1. Acknowledgements The Fellow Brian Maxwell would like to thank the following individuals and organisations Governance and Management who generously gave their time and their expertise to assist, advise and guide him throughout his Perpetual Foundation: Eddy Dunn Endowment International Fellowship. Patron in Chief: Lady Primrose Potter AC Patrons: Mr. Tony Schiavello AO and Mr. James MacKenzie Awarding Body – International Specialised Skills Institute (ISS Institute) Sir James Gobbo AC, CVO The ISS Institute plays a pivotal role in creating value and opportunity, encouraging new Founder/Board Member: thinking and early adoption of ideas and practice by investing in individuals. Board Chair: Professor Amalia Di Iorio Mark Kerr The overarching aim of the ISS Institute is to support the development of a ‘Better Skilled Board Deputy Chair: Australia’. The Institute does this via the provision of Fellowships that provide the Board Treasurer: Jack O’Connell -

Plastering and Drywall Systems Construction and Building Technology

Technical Description Plastering and Drywall Systems Construction and Building Technology © WorldSkills International TD21 v7.0 WSC2019 WorldSkills International, by a resolution of the Competitions Committee and in accordance with the Constitution, the Standing Orders, and the Competition Rules, has adopted the following minimum requirements for this skill for the WorldSkills Competition. The Technical Description consists of the following: 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 2 2 THE WORLDSKILLS STANDARDS SPECIFICATION (WSSS) .............................................................. 4 3 THE ASSESSMENT STRATEGY AND SPECIFICATION ..................................................................... 10 4 THE MARKING SCHEME .................................................................................................................. 11 5 THE TEST PROJECT .......................................................................................................................... 16 6 SKILL MANAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION ............................................................................ 20 7 SKILL-SPECIFIC SAFETY REQUIREMENTS ....................................................................................... 21 8 MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT ....................................................................................................... 22 9 SKILL-SPECIFIC RULES .................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 1 – History of Lath & Plaster

CHAPTER 1 – HISTORY OF LATH & PLASTER /2011 15 12/ : HISTORY OF& PLASTER LATH : HISTORY CHAPTER 1CHAPTER 1-1 CHAPTER 1 – HISTORY OF LATH & PLASTER TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORIC ACCOUNTS PAGE 1-3 OVERVIEW PAGE 1-4 BENEFITS OF PLASTER/STUCCO PAGE 1-4 SEISMIC BENEFITS PAGE 1-5 LIME PLASTER PAGE 1-5 GYPSUM PLASTER PAGE 1-6 PORTLAND CEMENT PLASTER-STUCCO PAGE 1-7 SKILL SETS PAGE 1-10 MOISTURE MANAGEMENT PAGE 1-10 PAGE 1-10 MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS/ASSEMBLIES /2011 PAGE 1-10 THE BARRIER CONCEPT 15 CONCEALED BARRIER CONCEPT PAGE 1-11 RAINSCREEN CONCEPT PAGE 1-11 12/ MOISTURE (RAIN) & DESIGN PRESSURE DATA PAGE 1-12 WINDOWS & DOORS – RELATED DESIGN PRESSURE PAGE 1-12 WINDOW DESIGN & FLASHINGS PAGE 1-13 STORE FRONT WINDOW PAGE 1-13 NAIL FLANGE WINDOW PAGE 1-14 FLASHING WINDOW & DOOR OPENINGS PAGE 1-14 PERFORMANCE GRADE WINDOWS PAGE 1-14 VAPOR & VAPOR DRIVE PAGE 1-15 PAGE 1-16 VAPOR CONTROL VAPOR RETARDER REQUIRMENTS PAGE 1-16 VAPOR RETARDERS & THE CODE PAGE 1-17 VAPOR PERMEABILITY PAGE 1-17 MATERIAL PERM RATINGS PAGE 1-18 WATER-RESISTIVE BARRIERS (WRB) PAGE 1-19 AIR BARRIERS PAGE 1-19 INNOVATIONS IN LATH & PLASTER PAGE 1-21 EIFS PAGE 1-21 ONE COAT STUCCO PAGE 1-22 DIRECT-APPLIED FINISH SYSTEMS PAGE 1-22 CEMENT BOARD SYSTEMS PAGE 1-22 “CI” PLASTER/STUCCO PAGE 1-23 THE HISTORY OF “THE LEAKY BUILDING CRISIS” PAGE 1-23 THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES PAGE 1-23 THE SEVENTIES & EIGHTIES PAGE 1-24 THE NINETIES & 2000 PAGE 1-25 OF& PLASTER LATH : HISTORY WHY DID EIFS GET THE BLAME? PAGE 1-25 THE FUTURE PAGE 1-25 CHAPTER 1CHAPTER 1-2 CHAPTER 1 – HISTORY OF LATH & PLASTER HISTORIC ACCOUNTS We can find the use of lime stucco and plasterers with exquisite composition, white, fine and thin, often no thicker than an eggshell in very early Greek Architecture.