THE ELEMENTS at RISK and THEIR VULNERABILITY Shelter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powerpoint Presentation Rebuttal "The Morayfield Office Was Opened

PowerPoint Presentation Rebuttal "The Morayfield office was opened in 2018 as a trial to reach into the northern area of the SEQ public transport network to provide greater revenue protection presence in this area." Area of Address Evidence Comments "Trial" Email "DDG has approved the Date: 05/06/2017 11:35am northern outpost which will Author: Michael Gordon be situated at Morayfield." Email "Expressions of Interest to Date: 10/10/2017 13:09pm go to Morayfield are being Author: Robert Tulleners taken for SNO's to permanently relocate to this office" Email "… to relocate to our new Date: 04/10/2017 08:19am office currently being fitted Author: Robert Tulleners out in Morayfield." Email: "… Added to this vacancy I Date: 20/05/2020 13:49pm need to finalise the Author: Peter Walsh evaluation of the Morayfield Supervisor Position with a view to making this a permeant vacancy. I am currently working with the HR team to get both of these positions finalised so that we can fill them, so stay tuned for more information shortly. Ministerial Release "For the first time, a Date: 29/03/2018 13:00 dedicated team of TransLink Authors: Senior Network Officers Minister for Transport Mark (SNO's) will be permanently Bailey based in the northern regions Minister for Police and of the South East Minister for Corrective Queensland public transport Services Mark Ryan network, following a new patrol base becoming operational in the weekend." Trail Focus claim: Ministerial Release "The base and SNO team will Date: 29/03/2018 13:00 ensure enhanced customer "Greater -

Inner Brisbane Heritage Walk/Drive Booklet

Engineering Heritage Inner Brisbane A Walk / Drive Tour Engineers Australia Queensland Division National Library of Australia Cataloguing- in-Publication entry Title: Engineering heritage inner Brisbane: a walk / drive tour / Engineering Heritage Queensland. Edition: Revised second edition. ISBN: 9780646561684 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Brisbane (Qld.)--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--Buildings, structures, etc.--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Engineers Australia. Queensland Division. Dewey Number: 919.43104 Revised and reprinted 2015 Chelmer Office Services 5/10 Central Avenue Graceville Q 4075 Disclaimer: The information in this publication has been created with all due care, however no warranty is given that this publication is free from error or omission or that the information is the most up-to-date available. In addition, the publication contains references and links to other publications and web sites over which Engineers Australia has no responsibility or control. You should rely on your own enquiries as to the correctness of the contents of the publication or of any of the references and links. Accordingly Engineers Australia and its servants and agents expressly disclaim liability for any act done or omission made on the information contained in the publication and any consequences of any such act or omission. Acknowledgements Engineers Australia, Queensland Division acknowledged the input to the first edition of this publication in 2001 by historical archaeologist Kay Brown for research and text development, historian Heather Harper of the Brisbane City Council Heritage Unit for patience and assistance particularly with the map, the Brisbane City Council for its generous local history grant and for access to and use of its BIMAP facility, the Queensland Maritime Museum Association, the Queensland Museum and the John Oxley Library for permission to reproduce the photographs, and to the late Robin Black and Robyn Black for loan of the pen and ink drawing of the coal wharf. -

New Style Metlink Timetables ΠSee Page 6

August 2005, Number 157 RRP $2.95 ISSN 1038-3697 New style Metlink timetables œ see page 6 Table Talk August 2005 Page 1 Top Table Talk: • Yarra trams 75 extended to Vermont south œ see page 4 • New style Metlink timetables in Melbourne œ see page 6 • Manly ferry troubles œ see page 10 Table Talk is published monthly by the Australian Association of Timetable Collectors Inc. [Registration No: A0043673H] as a journal covering recent news items. The AATTC also publishes The Times covering historic and general items. Editor: Duncan MacAuslan, 19 Ellen Street, Rozelle, NSW, 2039 œ (02) 9555 2667, dmacaus1@ bigpond.net.au Editorial Team: Graeme Cleak, Lourie Smit. Production: Geoff and Judy Lambert, Chris London Secretary: Steven Ward, 12/1219 Centre Road, South Oakleigh, VIC, 3167, (03) 9540 0320 AATTC on the web: www.aattc.org.au Original material appearing in Table Talk may be reproduced in other publications, acknowledgement is required. Membership of the AATTC includes monthly copies of The Times, Table Talk, the distribution list of TTs and the twice-yearly auction catalogue. The membership fee is $50.00 pa. Membership enquiries should be directed to the Membership Officer: Dennis McLean, PO Box 24, Nundah, Qld, 4012, Australia. Phone (07) 3266 8515.. For the Record Contributors: Tony Bailey, Chis Brownbill, Derek Cheng, Anthony Christie, Graeme Cleak, Michael Coley, Ian Cooper, Ken Davey, Adrian Dessanti, Graham Duffin, Noel Farr, Neville Fenn, Paul Garred, Alan Gray, Steven Haby, Craig Halsall, Robert Henderson, Michael Hutton, Albert Isaacs, Bob Jackson, Matthew Jennings, Peter Jones, Geoff Lambert, Julian Mathieson, Michael Marshall, John Mikita, Peter Murphy, Len Regan, Graeme Reynolds, Scott Richards, Lourie Smit, Tris Tottenham, Craig Watkins, Roger Wheaton, David Whiteford. -

Planning and Environment Court of Queensland

PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT COURT OF QUEENSLAND CITATION: Body Corporate for Mayfair Residences Community Titles Scheme 31233 v Brisbane City Council & Anor [2017] QPEC 22 PARTIES: BODY CORPORATE FOR MAYFAIR RESIDENCES COMMUNITY TITLES SCHEME 31233 (appellant) v BRISBANE CITY COUNCIL (respondent) and THE TRUSTEE FOR THE ATHOL PLACE PROPERTY TRUST (co-respondent) FILE NO/S: 3467 of 2016 DIVISION: Planning and Environment Court PROCEEDING: Planning and Environment Appeal ORIGINATING COURT: Brisbane DELIVERED ON: 26 April 2017 DELIVERED AT: Brisbane HEARING DATE: 23, 24 and 28, 29, 31 March 2017 and 5 April 2017 JUDGE: Kefford DCJ ORDER: The appeal will, in due course, be dismissed. I will adjourn the further hearing to allow for the formulation of conditions. CATCHWORDS: PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT – appeal against approval of a development application for material change of use – proposed development for re-use of heritage place, office, health care services and food and drink outlet – whether there is conflict occasioned by bulk and scale – whether there is conflict with the planning intent for the Petrie Terrace and Spring Hill Neighbourhood Plan area - whether there will be unacceptable amenity and character impacts – whether cultural heritage significance is protected - whether there are sufficient grounds to approve the proposed development despite conflict with the planning scheme – whether there is a need for the proposed development 2 Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld), s 314, s 324, s 326, s 462, s 493, s 495 Acland Pastoral Co Pty -

Question on Notice No. 31 Asked on Tuesday 12 February 2019 MS F

Question on Notice No. 31 Asked on Tuesday 12 February 2019 MS F SIMPSON ASKED MINISTER FOR TRANSPORT AND MAIN ROADS (HON M BAILEY) QUESTION: With regards to fare evasion on Sunbus services across the Sunshine Coast— Will the Minister advise (a) for 2018 (i) how many times Senior Network Officers were deployed on Sunbus services, (ii) how many warnings and penalty infringement notices were issued and (b) what the Minister is doing to address security and fare evasion issues? ANSWER: I thank the Member for Maroochydore for the question. The Palaszczuk Government takes the issue of fare evasion seriously and is committed is committed to addressing this issue. The Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR) employs a frontline operational workforce of 55 senior network officers (SNOs) who work alongside 27 Queensland Rail authorised officers, 78 Queensland Police Service (QPS) rail squad officers and 31 GoldlinQ customer service officers to stage regular station lockdowns and patrols, educate public transport users, and issue penalty infringements and warning notices. A further round of recruitment for SNOs is about to get underway with advertisements appearing in the next few weeks. The safety of passengers is always a priority for the Palaszczuk Government. At the same time, there is a strong community expectation that users of the public transport network accept their responsibility to pay their fares. In 2018, SNOs were deployed on Sunshine Coast Sunbus services a total of 572 times, and issued 12 Penalty Infringement Notices and 215 -

Annual Report 2013—2014 Volume 1 of 2

Volume 1 of 2 About the report What the report contains For more information The Department of Transport and Main Roads Annual Phone: +617 3066 7381 Report 2013–14 describes the department’s operations for the financial year from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. It also Email: [email protected] presents our priorities for the forthcoming financial year Visit: Transport and Main Roads website www.tmr.qld.gov.au of 2014–15. Annual report website: www.qld.gov.au/about/staying- informed/reports-publications/annual-reports/ Why we have an annual report You can provide feedback on the annual report at the Queensland Government Get Involved website at As well as meeting the statutory requirement set out in www.qld.gov.au/annualreportfeedback. the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, the annual The Queensland Government is committed to report is a vital tool in keeping the community, industry, providing accessible services to Queenslanders government and organisations informed about our from all culturally and linguistically diverse performance and future direction. backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding the annual report, you can contact us on 13 23 80* and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively Accessing the report communicate the report to you. The annual report is available on the Department of * Local call charge in Australia. Higher rates apply from mobile phones and payphones. Check with your service provider for call costs. For Transport and Main Roads website at www.tmr.qld.gov.au international callers, please phone +61 7 3834 2011. -

Brisbane to Gold Coast Train Timetable

Airport–City to Varsity Lakes outbound Monday to Friday services General information Abbreviations Departs Comes from SHC Fri All customers travelling on TransLink services must be in every possession of a valid ticket before boarding. For ticket Departs Services depart at time indicated within Station am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm pm am information, please ask at your local station or call 13 12 30. every the hour Domestic ... 5:42 6:00 6:28 6:58 7:28 7:58 8:14 8:29 8:44 8:59 9:14 9:28 9:44 9:58 :28 :58 3:28 3:45 3:58 4:13 4:28 4:48 5:02 . 5:30 5:45 5:58 6:28 6:58 7:13 7:28 8:00 .... While Queensland Rail makes every effort to ensure This station has a connecting bus service International ... 5:45 6:03 6:31 7:01 7:31 8:01 8:17 8:32 8:47 9:02 9:17 9:31 9:47 10:01 :31 :01 3:31 3:48 4:01 4:16 4:31 4:51 5:05 . 5:33 5:48 6:01 6:31 7:01 7:16 7:31 8:03 .... trains run as scheduled, there can be no guarantee of Parking available Eagle Junction pform ... #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 #1 ... -

Drinking Water Quality Report

DRINKING WATER QUALITY REPORT 2014 -2015 Contents Dear Customers, Each year Unitywater publishes this report to set out transparently information about the quality of the drinking water Message from the CEO .........................................................3 we supply. I’m pleased to confirm that during 2014-15 the water supplied to our customers remained of a very high standard and, Our supply area ......................................................................4 as in previous years, met all regulatory requirements. Water supply sources ............................................................6 Unitywater continues to meet the requirements set by the Water quality summary ........................................................8 Queensland Public Health Regulation for drinking water, with Your suburb and its water supply region ......................... 10 99.9% of all samples free of E. coli, an indicator of possible contamination. Meeting this requirement demonstrates that Drinking water quality performance ................................. 12 you can continue to have confidence in the water supplied by Microbiological performance in detail .............................. 13 Unitywater to your home, school and work place. To maintain that confidence Unitywater sampled and completed almost Chemical performance in detail ......................................... 14 100,000 individual water tests. Of those only five did not meet an individual guideline. Each of these was investigated promptly Bribie Island ................................................................... -

Annual Report 2013—2014 Volume 1 of 2

Volume 1 of 2 About the report What the report contains For more information The Department of Transport and Main Roads Annual Phone: +617 3066 7381 Report 2013–14 describes the department’s operations for the financial year from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. It also Email: [email protected] presents our priorities for the forthcoming financial year Visit: Transport and Main Roads website www.tmr.qld.gov.au of 2014–15. Annual report website: www.qld.gov.au/about/staying- informed/reports-publications/annual-reports/ Why we have an annual report You can provide feedback on the annual report at the Queensland Government Get Involved website at As well as meeting the statutory requirement set out in www.qld.gov.au/annualreportfeedback. the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, the annual The Queensland Government is committed to report is a vital tool in keeping the community, industry, providing accessible services to Queenslanders government and organisations informed about our from all culturally and linguistically diverse performance and future direction. backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding the annual report, you can contact us on 13 23 80* and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively Accessing the report communicate the report to you. The annual report is available on the Department of * Local call charge in Australia. Higher rates apply from mobile phones and payphones. Check with your service provider for call costs. For Transport and Main Roads website at www.tmr.qld.gov.au international callers, please phone +61 7 3834 2011. -

Adverse Weather Effects on Bus Ridership

26th ARRB Conference – Research driving efficiency, Sydney, New South Wales 2014 ADVERSE WEATHER EFFECTS ON BUS RIDERSHIP Syeed Anta Kashfi, Queensland University of Technology, Australia Associate Professor Jonathan Bunker, Queensland University of Technology, Australia ABSTRACT This study focuses on weather effects on daily bus ridership in Brisbane, given bus’ dominance in this city. The weather pattern of Brisbane varies by season according to its sub-tropical climate characteristics. Bus is prone to inclement weather condition as it shares the road system with general traffic. Moreover, bus stops generally offer less or sometimes no protection from adverse weather. Hence, adverse weather conditions such as rain are conjectured to directly impact on daily travel behaviour patterns. There has been limited Australian research on the impact of weather on daily transit ridership. This study investigates the relationship between rainy day and daily bus ridership for the period of 2010 to 2012. Overall, rainfall affects negatively with varying impacts on different transit groups. However, this analysis confirmed a positive relationship between consecutive rainy days (rain continuing for 3 or more days). A possible explanation could be that people may switch their transport mode to bus to avoid high traffic congestion and higher accident potentiality on rainy days. Also, Brisbane’s segregated busway (BRT) corridor works favourably towards this mode choice. Our study findings enhance the fundamental understanding of traveller behaviour, particularly mode choice behaviour under adverse weather conditions. INTRODUCTION A host of factors influence transit ridership either directly or indirectly including, but not limited to socio-economic characteristics of trip makers, household socio-economic characteristics, such as household size, structure and composition, housing tenure, lifestyle, and attitude towards using transit (Crowley, 2001; Zarei, 2007; Cervero and Kockelman, 1997). -

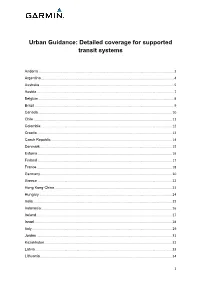

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

Ipswich in Nation's Top 10 Property Hotspots

Ipswich in Nation’s top 10 property hotspots JESSIE RICHARDSON | 26 AUGUST 2014 IPSWICH real estate capital growth is tipped to double the return of Brisbane properties in three years, experts predict. The property market’s recovery is expected to continue this year with signs of brighter future on the horizon. But the three-year outlook is promising, according to real estate analyst and hotspotting.com.au founder Terry Ryder. Mr Ryder expects the capital growth of Ipswich properties to rise by 15% over the next three years, compared with 7.5% in Brisbane properties. Whether or not Ipswich does perform as expected remains to be seen, but I have long viewed the city as one with great investment opportunity and in a real estate investment market that is still a little hit and miss at the moment, all indicators are that Ipswich is one of the safer bets in 2013. Big projects coming for Ipswich, in Brisbane's south west, include the $2.8 billion Ipswich Motorway Upgrade, $12 billion Springfield project, the $1.5 billion Springfield rail link and the Orion shopping centre, along with expansions to the RAAF base, and large industrial estates. Ryder also claims the area has a strong economy, with multiple employment hubs and affordable properties. "The Ipswich corridor is now well-known as a growth region. Prices rose strongly in the five years to 2009 (before tapering off), giving the suburbs of Ipswich City the strongest capital growth averages in the Greater Brisbane region," writes Ryder. "Ipswich has shown strong growth in the past but we believe its evolution into a headline hotspot of national standing will continue well into the future.