Six Lenses for Interpreting Theatre for Young Australian Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ascacut Paper 6/15/16, 10:12 AM

ASCAcut paper 6/15/16, 10:12 AM TO HEAL THE GAP BETWEEN SUBJECT AND PROTAGONIST: RESTORING FEMALE AGENCY WITH IMMERSION AND INTERACTIVITY Paper for ASCA Mini-Conference June 8, 2001, Amsterdam By Alison McMahan, Ph.D. Mieke Bal, in her book Reading "Rembrandt", critiques the so-called universalism of the myth genre of storytelling because this claim to universalism conceals the split between "the subject who tells the story about itself and the subject it tells about." (Mieke Bal, "Visual Story-Telling: Father and |Son and the Problem of Myth." From Reading "Rembrandt": Beyond the Word-Image Opposition, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1991,p.98). In her articulation of the differences between the latter two terms and her analysis of visuality in the literary accounts and of the Rembrandt images, Bal shows us how the method of discourse separates protagonist from subject, specifically, the female subject, and makes the role of protagonist inaccessible for other females. The voyeuristic spectator is invited into a position of internal focalization in Rembrandt’s etching, which incriminates the spectator, though she be female and feminist, into a site of “interpretants shaped by a male habit.” There are two solutions: the awareness created by an against-the-grain analysis, such as Kaja Silverman’s “productive looking” or to change how the story is told. Feminine agency, (“feminine” here is defined as the socially constructed ideas attached to the female sex. Poststructuralists feminists deconstruct texts in order to make explicit the power relations that structure discourse), on earth or between the pages, cannot be restored unless the gap between subject and protagonist is healed and re-adressed. -

Shropshire Cover

Wolverhampton & Black Country Cover February 2020.qxp_Wolverhampton & Black Country Cover 22/01/2020 14:55 Page 1 THE RED SHOES RETURNS Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands TO THE MIDLANDS... WOLVERHAMPTON & BLACK COUNTRY WHAT’S ON FEBRUARY 2020 FEBRUARY ON WHAT’S COUNTRY BLACK & WOLVERHAMPTON Wolverhampton & Black Country ISSUE 410 FEBRUARY 2020 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On wolverhamptonwhatson.co.uk inside: PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide AFTER HENRY Henry VIII’s wives visit the Grand Theatre in SIX TWITTER: @WHATSONWOLVES @WHATSONWOLVES TWITTER: BEN POOLE award-winning guitarist plays the blues at The Robin FACEBOOK: @WHATSONWOLVERHAMPTON FACEBOOK: @WHATSONWOLVERHAMPTON RAIN OR SHINE... places to visit during the WOLVERHAMPTONWHATSON.CO.UK February school holiday IFC Wolverhampton.qxp_Layout 1 22/01/2020 15:51 Page 1 Thursday 6th - Saturday 8th February at Thursday 13th February at 7.30pm Friday 14th February at 7.30pm 7.30pm, 1pm Friday Matinee Drama Drama Dance JANEJANE EYREEYRE LOOKING FOR WOLVERHAMTON'S EMERGENCEEMERGENCE TRIPLETR BILL LATIN QUARTER 2020 Tickets £10 Tickets £10 Tickets £10 Saturday 15th February at 7.30pm Friday 21st - Sunday 23rd February at Thursday 27th February at 7.30pm 7.00pm Friday and Saturday, 2.00pm Saturday and Sunday Drama Musical Theatre DRAMA YOURS SINCERELY FOOTLOOSE HOME OF THE WRIGGLER Tickets £10 Tickets £12, £10 conc Tickets £10 Contents February Wolves/Shrops/Staffs.qxp_Layout 1 22/01/2020 16:08 Page 2 February 2020 Contents The Queendom Is Coming.. -

'Made in China': a 21St Century Touring Revival of Golfo, A

FROM ‘MADE IN GREECE’ TO ‘MADE IN CHINA’ ISSUE 1, September 2013 From ‘Made in Greece’ to ‘Made in China’: a 21st Century Touring Revival of Golfo, a 19th Century Greek Melodrama Panayiota Konstantinakou PhD Candidate in Theatre Studies, Aristotle University ABSTRACT The article explores the innovative scenographic approach of HoROS Theatre Company of Thessaloniki, Greece, when revisiting an emblematic text of Greek culture, Golfo, the Shepherdess by Spiridon Peresiadis (1893). It focuses on the ideological implications of such a revival by comparing and contrasting the scenography of the main versions of this touring work in progress (2004-2009). Golfo, a late 19th century melodrama of folklore character, has reached over the years a wide and diverse audience of both theatre and cinema serving, at the same time, as a vehicle for addressing national issues. At the dawn of the 21st century, in an age of excessive mechanization and rapid globalization, HoROS Theatre Company, a group of young theatre practitioners, revisits Golfo by mobilizing theatre history and childhood memory and also by alluding to school theatre performances, the Japanese manga, computer games and the wider audiovisual culture, an approach that offers a different perspective to the national identity discussion. KEYWORDS HoROS Theatre Company Golfo dramatic idyll scenography manga national identity 104 FILMICON: Journal of Greek Film Studies ISSUE 1, September 2013 Time: late 19th century. Place: a mountain village of Peloponnese, Greece. Golfo, a young shepherdess, and Tasos, a young shepherd, are secretly in love but are too poor to support their union. Fortunately, an English lord, who visits the area, gives the boy a great sum of money for rescuing his life in an archaeological expedition and the couple is now able to get engaged. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

04 Part Two Chapter 4-5 Everett

PART TWO. "So what are you doing now?" "Well the school of course." "You mean youre still there?" "Well of course. I will always be there as long as there are students." (Jacques Lecoq, in a letter to alumni, 1998). 79 CHAPTER FOUR INTRODUCTION TO PART TWO. The preceding chapters have been principally concerned with detailing the research matrix which has served as a means of mapping the influence of the Lecoq school on Australian theatre. I have attempted to situate the research process in a particular theoretical context, adopting Alun Munslow's concept of `deconstructionise history as a model. The terms `diaspora' and 'leavening' have been deployed as metaphorical frameworks for engaging with the operations of the word 'influence' as it relates specifically to the present study. An interpretive framework has been constructed using four key elements or features of the Lecoq pedagogy which have functioned as reference points in terms of data collection, analysis and interpretation. These are: creation of original performance material; use of improvisation; a movement-based approach to performance; use of a repertoire of performance styles. These elements or `mapping co-ordinates' have been used as focal points during the interviewing process and have served as reference points for analysis of the interview material and organisation of the narrative presentation. The remainder of the thesis constitutes the narrative interpretation of the primary and secondary source material. This chapter aims to provide a general overview of, and introduction to the research findings. I will firstly outline a demographic profile of Lecoq alumni in Australia. Secondly I will situate the work of alumni, and the influence of their work on Australian theatre within a broader socio-cultural, historical context. -

Acting with Care: How Actor Practice Is Shaped by Creating Theatre with and for Children – Jennifer Andersen Declaration

Acting with care: How actor practice is shaped by creating theatre with and for children Jennifer Andersen ORCID ID: D-4258-2015 Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 Melbourne Graduate School of Education The University of Melbourne Abstract Research has investigated the backgrounds, dispositions and skills of artists working with children in both school and in out-of-school contexts (Ascenso, 2016; Brown, 2014; Galton, 2008; Jeanneret & Brown, 2013; Pringle, 2002; Pringle, 2009; Rabkin, Reynolds, Hedberg, & Shelby, 2008; Waldorf, 2002). Actors make a significant contribution to this work but few studies focus in depth on how they create theatre with and for children. Incorporating constructivist, phenomenological (Van Manen, 1990) and case study methodologies, this research investigates the practice of nine actors who create theatre with and for children in diverse contexts. Drawing on document analysis, surveys, semi- structured interviews and performance observations, the research explores two key questions: What characterises the practice of actors who create theatre with and for children? and How is actor practice shaped by working with children? This thesis explores actor practice in relation to being, doing, knowing and becoming (Ewing & Smith, 2001). Shaped to be outward facing and ‘pedagogically tactful’ (Van Manen, 2015), actor practice gives emphasis to four key qualities: listening, reciprocating, imagining and empathising. When creating theatre with and for children, pedagogically tactful actors are guided by a sense of care and respect. This thesis adds to the discourse about artists working with children, making actor practice visible and drawing attention to their beliefs, goals, motivations and acting techniques. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Talking Books for Children – Ausgewählte Untersuchungen Zum Hörbuchangebot Für Kinder in Australien

Talking books for children – Ausgewählte Untersuchungen zum Hörbuchangebot für Kinder in Australien Diplomarbeit im Fach Kinder- und Jugendmedien Studiengang Öffentliche Bibliotheken der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Daniela Kies Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Horst Heidtmann Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Manfred Nagl Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15. Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Gegenstand der hier vorgestellten Arbeit ist das Hörbuchangebot für Kinder in Austra- lien. Seit Jahren haben Gesellschaften für Blinde Tonträger für die eigenen Bibliothe- ken produziert, um blinden oder sehbehinderten Menschen zu helfen. Hörmedien von kommerziellen Produzenten, in Australien ist ABC Enterprises der größte, sind in der Regel gekürzte Versionen von Büchern. Bolinda Audio arbeitet kommerziell, veröffent- licht aber nur ungekürzte Versionen. Louis Braille Audio und VoyalEyes sind Abteilun- gen von Organisationen für Blinde, die Tonträger auch an Bibliotheken verkaufen und sie sind auch im Handel erhältlich. Grundsätzlich gelten öffentliche Bibliotheken als Hauptzielgruppe und ihnen werden spezielle Dienstleistungen von den Verlagen selbst oder dem Bibliothekszulieferer angeboten. Die britische und amerikanische Konkurrenz ist im Kindertonträgerbereich besonders groß. Aus diesem Grund spezialisieren sich australische Hörbuchverlage auf die Produktion von Büchern australischer Autoren und/ oder über Australien. Bei Kindern sind die Autoren John Marsden, Paul Jennings und Andy Griffiths sehr beliebt. Stig Wemyss, ein ausgebildeter Schauspieler, hat zahl- reiche Bücher bei verschiedenen Verlagen erfolgreich gelesen. Musik bzw. Lieder wer- den auf Hörbüchern nur vereinzelt verwendet. Es gibt aber einige Gruppen, z.B. die Wiggles, und Entertainer, z.B. Don Spencer, die Lieder für Kinder schreiben und auf- nehmen. Da der Markt für Kindertonträger in Australien noch im Aufbau ist, lohnt es sich, die Entwicklungen weiter zu verfolgen. -

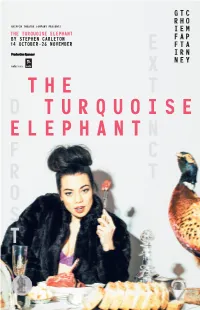

The Turquoise Elephant E X T D N F C R T O

GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS THE TURQUOISE ELEPHANT STEPHEN CARLETON BY STEPHEN CARLETON 14 OCTOBER-26 NOVEMBER E Production Sponsor Meet Augusta Macquarie: Her Excellency, patron of the arts, X formidable matriarch, environmental vandal. THE T D TURQUOISE Inside her triple-glazed compound, Augusta shields herself from the catastrophic elements, bathing in THE TURQUOISE ELEPHANT the classics and campaigning for the reinstatement of global reliance on fossil fuels. Outside, the world lurches from one environmental cataclysm to the next. ELEPHANT N Meanwhile, her sister, Olympia, thinks the best way to save endangered species is to eat them. Their niece, Basra, is intent on making a difference – but how? Can you save the world one blog at a time? F C Stephen Carleton’s shockingly black, black, black political farce won the 2015 Griffin Award. R T It’s urgent, contemporary and perilously close to being real. Director Gale Edwards brings her magic and wry insight to the world premiere of this very funny, clever and wicked new work. O S T CURRENCY PRESS GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS THE TURQUOISE ELEPHANT BY STEPHEN CARLETON 14 OCTOBER-26 NOVEMBER Director Gale Edwards Set Designer Brian Thomson Costume Designer Emma Vine Lighting and AV Designer Verity Hampson Sound Designer Jeremy Silver Associate Lighting Designer Daniel Barber Stage Manager Karina McKenzie Videographer Xanon Murphy With Catherine Davies, Maggie Dence, Julian Garner, Belinda Giblin, Olivia Rose, iOTA SBW STABLES THEATRE 14 OCTOBER - 26 NOVEMBER Production Sponsor Government Partners Griffin acknowledges the generosity of the Seaborn, Broughton and Walford Foundation in allowing it the use of the SBW Stables Theatre rent free, less outgoings, since 1986. -

Experiencing Theatres 9 June 2009

Conference 09 Report Experiencing Theatres 9 June 2009 Protecting theatres for everyone Sponsors Conference 09 Report Experiencing Theatres 9 June 2009 02 Conference 09 Report Experiencing Theatres Contents Mhora Samuel Director, The Theatres Trust ............... 04 David Benedict Conference 09 Chair .......................... 05 Introduction ......................................................................... 06 Transformation ................................................................... 07 Consultation........................................................................ 09 Conference Address ........................................................ 11 Hosting ................................................................................. 12 Influencing ........................................................................... 14 Audience Design Principles .......................................... 17 Attenders ............................................................................. 19 Conference Chairs Colin Blumenau Artistic Director, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds David Benedict Jenny Sealey MBE Artistic Director/CEO, Graeae Theatre Andrew Dickson Steve Tompkins Director, Haworth Tompkins Bonnie Greer John E McGrath Artistic Director, National Theatre Wales Conference 09 Reporter Jonathan Meth Executive Director, Theatre Is… Contributors Rt Hon Barbara Follett MP Minister for Culture, Creative Industries & Tourism Conference 09 Photographer Vikki Heywood Executive Director, Royal Shakespeare Company Edward Webb -

Benjamin Winspear

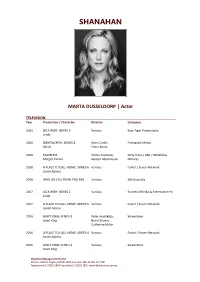

SHANAHAN MARTA DUSSELDORP | Actor TELEVISION Year Production / Character Director Company 2021 JACK IRISH: SERIES 3 Various Easy Tiger Productions Linda 2020 WENTWORTH: SERIES 8 Kevin Carlin, Fremantle Media Sheila Fiona Banks 2019 STATELESS Emma Freeman, Dirty Films / ABC / Matchbox Margot Verner Jocelyn Moorhouse Pictures 2018 A PLACE TO CALL HOME: SERIES 6 Various Foxtel / Seven Network Sarah Adams 2018 WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE Various SBS Australia 2017 JACK IRISH: SERIES 2 Various Essential Media & Entertainment Linda 2017 A PLACE TO CALL HOME: SERIES 5 Various Foxtel / Seven Network Sarah Adams 2016 JANET KING: SERIES 3 Peter Andrikidis, Screentime Janet King Grant Brown, Catherine Millar 2016 A PLACE TO CALL HOME: SERIES 4 Various Foxtel / Seven Network Sarah Adams 2015 JANET KING: SERIES 2 Various Screentime Janet King Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 JACK IRISH SERIES 1 Various Essential Media & Entertainment Linda 2015 A PLACE TO CALL HOME: SERIES 3 Various Foxtel / Seven Network Sarah Adams 2013 A PLACE TO CALL HOME: SERIES 2 Various Seven Network Sarah Adams 2013 JACK IRISH: DEAD POINT Jeffrey Walker Essential Media & Entertainment Linda Hillier 2013 JANET KING Various Screentime Janet King 2012 A PLACE TO CALL HOME: SERIES 1 Various Seven Network Operations Sarah Adams 2012 DEVIL’S DUST Jessica Hobbs Fremantle Media Meredith Hellicar 2012 JACK IRISH: BLACK TIDE Jeffrey Walker Essential -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything.