Vindiciae, Contra Tyrannos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcgill University

McGill University Faculty of Religious Studies RELG 323 CHURCH AND STATE SINCE 1300 A survey of major developments in the history of the doctrine and institutions of the Church, and the relation of the Church to the Commonwealth, from the later Middle Ages to the present. Birks Building, Room 105 Tuesdays/Thursdays 1:00—2:30 pm Professor: Torrance Kirby Office Hours: Birks 206, Tuesdays/Thursdays, 9:30—10:30 am Email: [email protected] COURSE SYLLABUS—WINTER TERM 2021 Date Reading 5 January INTRODUCTION I. LATE-MEDIEVAL CHURCH AND RENAISSANCE 7 January IMPERIAL SUPREMACY Boniface VIII, Unam Sanctam (1302) Marsilius of Padua, Defensor Pacis (1324) 12 January MYSTICAL SPIRITUALITY Julian of Norwich, Shewings of Divine Love (1393) 14 January ECCLESIASTICAL HIERARCHY Nicholas of Cusa, The Catholic Concordance (1433) 19 January NEOPLATONIC MYSTICISM Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) 21 January RENAISSANCE HUMANISM Nicollò Machiavelli, An Exhortation to Penitence (1495) II. REFORMATION 26 January JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH ALONE Martin Luther, Two Kinds of Righteousness (1520) 28 January A SEPARATE CHURCH Michael Sattler, Schleitheim Articles (1527) 2 February CHRISTIAN LIBERTY John Calvin, On the Necessity of Reforming the Church (1543) 4 February COUNTER REFORMATION Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual Exercises (1548) Teresa of Ávila, The Way of Perfection (1573) Confirm Mid-Term Essay Topics Please consult style sheet, essay-writing guidelines, and evaluation rubric. 9 February RIGHT OF RESISTANCE Philippe Duplessis-Mornay, A Defence of Liberty against tyrants (1579) 11 February ERASTIANISM Richard Hooker, Of the Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Politie (1593) RELG 323 CHURCH AND STATE SINCE 1300 2 Date Reading III. -

H. Doc. 108-222

THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES 1789–2005 [ 43 ] TIME AND PLACE OF MEETING The Constitution (Art. I, sec. 4) provided that ‘‘The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year * * * on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.’’ Pursuant to a resolution of the Continental Congress the first session of the First Congress convened March 4, 1789. Up to and including May 20, 1820, eighteen acts were passed providing for the meet- ing of Congress on other days in the year. Since that year Congress met regularly on the first Mon- day in December until January 1934. The date for convening of Congress was changed by the Twen- tieth Amendment to the Constitution in 1933 to the 3d day of January unless a different day shall be appointed by law. The first and second sessions of the First Congress were held in New York City; subsequently, including the first session of the Sixth Congress, Philadelphia was the meeting place; since then Congress has convened in Washington, D.C. [ 44 ] FIRST CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1789, TO MARCH 3, 1791 FIRST SESSION—March 4, 1789, 1 to September 29, 1789 SECOND SESSION—January 4, 1790, to August 12, 1790 THIRD SESSION—December 6, 1790, to March 3, 1791 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN ADAMS, of Massachusetts PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN LANGDON, 2 of New Hampshire SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, 3 of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, 4 of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—FREDERICK A. -

A Genealogy of the Hiester Family

Gc 929.2 H532h 1339494 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 03153 3554 A GENEALOGY The Hiester Family By V. E. a HILL PRINTED FOR PRIVATE DISTRIBUTION LEBANON. PA. REPORT PUBLISHING COMPANY 1903 1339494 1 "Knowledge of kindred and the genealogies of the ancient families v' dcscrvcth the highest praise. Herein consisteth a part of the knowledge of a man's own self. It is a great spur to virtue to look hack on the worth ^-} of our line."—Lord Bacon. Coat of Arms of the Hiester Family. [Copiei] from a record of the Hiester family by Mr. H. M. M. Richards, of Beading, THE origin of the Hiester Family was the Silesian knight, Premiscloros Hiisterniz, who flourished about 1329, and held the office of Mayor, or Town Captain of the city of Swineford. "A. D. 1480, the Patrician and Counsellor of Swineford, Adol- phus Louis, called 'der Hiester,' obtained from the Emperor Frederick, letters patent whereby he and his posterity were au- thorized to use the coat-of-arms he had inherited from his ances- tors, to whom it was formerly granted, with the faculty of trans- mitting the same as an hereditary right and privilege to all his descendants. "The Hiester family was afterward diffused through Austria, Saxony, Switzerland and other countries bordering on the river Rhine. Several of the members were distinguished statesmen and ministers of religion and among the Senators of Homburg, B-emen and Ratisbon, where many of the same name were found who afterward held the highest and most important offices in said cities. The first part of this sketch Is a translatiou from the German by G. -

Philip Sidney's Book-Buying at Venice and Padua, Giovanni Varisco's Venetian Editions of Jacopo Sannazaro's Arcadia

This is a repository copy of Philip Sidney's Book-Buying at Venice and Padua, Giovanni Varisco's Venetian editions of Jacopo Sannazaro's Arcadia (1571 and 1578) and Edmund Spenser's The Shepheardes Calender (1579). White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/136570/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Brennan, MG orcid.org/0000-0001-6310-9722 (2018) Philip Sidney's Book-Buying at Venice and Padua, Giovanni Varisco's Venetian editions of Jacopo Sannazaro's Arcadia (1571 and 1578) and Edmund Spenser's The Shepheardes Calender (1579). Sidney Journal, 36 (1). pp. 19-40. ISSN 1480-0926 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Philip Sidney’s Book-Buying at Venice and Padua, Giovanni Varisco’s Venetian editions of Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia (1571 and 1578) and Edmund Spenser’s The Shepheardes Calender (1579)1 [Abstract] This essay traces Philip Sidney’s involvements with the book trade at Venice and Padua during his residence there from November 1573 until August 1574. -

Biographies 1169

Biographies 1169 also engaged in agricultural pursuits; during the First World at Chapel Hill in 1887; studied law; was admitted to the War served as a second lieutenant in the Three Hundred bar in 1888 and commenced practice in Wilkesboro, N.C.; and Thirteenth Trench Mortar Battery, Eighty-eighth Divi- chairman of the Wilkes County Democratic executive com- sion, United States Army, 1917-1919; judge of the municipal mittee 1890-1923; member of the Democratic State executive court of Waterloo, Iowa, 1920-1926; county attorney of Black committee 1890-1923; mayor of Wilkesboro 1894-1896; rep- Hawk County, Iowa, 1929-1934; elected as a Republican to resented North Carolina at the centennial of Washington’s the Seventy-fourth and to the six succeeding Congresses inauguration in New York in 1889; unsuccessful candidate (January 3, 1935-January 3, 1949); unsuccessful candidate for election in 1896 to the Fifty-fifth Congress; elected as for renomination in 1948 to the Eighty-first Congress; mem- a Democrat to the Sixtieth Congress (March 4, 1907-March ber of the Federal Trade Commission, 1953-1959, serving 3, 1909); unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1908 to as chairman 1955-1959; retired to Waterloo, Iowa, where the Sixty-first Congress; resumed the practice of law in he died July 5, 1972; interment in Memorial Park Cemetery. North Wilkesboro, N.C.; died in Statesville, N.C., November 22, 1923; interment in the St. Paul’s Episcopal Churchyard, Wilkesboro, N.C. H HACKETT, Thomas C., a Representative from Georgia; HABERSHAM, John (brother of Joseph Habersham and born in Georgia, birth date unknown; attended the common uncle of Richard Wylly Habersham), a Delegate from Geor- schools; solicitor general of the Cherokee circuit, 1841-1843; gia; born at ‘‘Beverly,’’ near Savannah, Ga., December 23, served in the State senate in 1845; elected as a Democrat 1754; completed preparatory studies and later attended to the Thirty-first Congress (March 4, 1849-March 3, 1851); Princeton College; engaged in mercantile pursuits; served died in Marietta, Ga., October 8, 1851. -

Lpennmglvaniaerman Genealogies

C KN LE D M E A OW G NT . Whil e under o bl ig a t io n s to various friends who have aided him in the compilation of this genealogy , the author desires to acknowledge especially the valuable assistance rendered him E . by Mrs . S . S . Hill (M iss Valeria Clymer) C O P YR IG HT E D 1 907 B Y T HE p ennspl vaniazmet m an S ociety . GENEALOGY O THE HIESTE R F MI F A LY. SCUTCHEON : A r is zu e , o r . a Sun , Crest : B e tween two horns , surm ount o ffr o n t é ing a helmet , a sun m as in the Ar s . Th e origin of the Hiester family was the Silesian Knight Pr em iscl o ro s Hii s t e rn iz flo , who urished about 1 3 2 9 and held the o fli ce o r T of Mayor, own Cap o f tain , the city of Swine ford . f . 1 o A D . 4 8 0 the Patrician and Counsellor Swineford , ( Adolphus Louis , called der Hiester , obtained from the E mperor Frederick letters patent , whereby he and his posterity were authorized t o use the coat- o f- arms he had inherited from his ancestors , to whom it was formerly o f granted , with the faculty transmitting the same , as an hereditary right and privilege , to all his descendants . - - - D r . o n Lawrence Hiester , b Frankfort the Main , Sep 1 1 6 8 . 1 8 1 tember 9 , 3 , d Helmstedt , April , 7 5 8 , Professor 1 2 0 of Surgery at Helmstedt from 7 , and the founder of 6 n n a n i e r m a n o e t Th e P e sylv a G S ci y . -

Germany and the Coming of the French Wars of Religion: Confession, Identity, and Transnational Relations

Germany and the Coming of the French Wars of Religion: Confession, Identity, and Transnational Relations Jonas A. M. van Tol Doctor of Philosophy University of York History February 2016 Abstract From its inception, the French Wars of Religion was a European phenomenon. The internationality of the conflict is most clearly illustrated by the Protestant princes who engaged militarily in France between 1567 and 1569. Due to the historiographical convention of approaching the French Wars of Religion as a national event, studied almost entirely separate from the history of the German Reformation, its transnational dimension has largely been ignored or misinterpreted. Using ten German Protestant princes as a case study, this thesis investigates the variety of factors that shaped German understandings of the French Wars of Religion and by extension German involvement in France. The princes’ rich and international network of correspondence together with the many German-language pamphlets about the Wars in France provide an insight into the ways in which the conflict was explained, debated, and interpreted. Applying a transnational interpretive framework, this thesis unravels the complex interplay between the personal, local, national, and international influences that together formed an individual’s understanding of the Wars of Religion. These interpretations were rooted in the longstanding personal and cultural connections between France and the Rhineland and strongly influenced by French diplomacy and propaganda. Moreover, they were conditioned by one’s precise position in a number of key religious debates, most notably the question of Lutheran-Reformed relations. These understandings changed as a result of a number pivotal European events that took place in 1566 and 1567 and the conspiracy theories they inspired. -

3. Pentland MS 142-Final

66 Early Modern Studies Journal Volume 6: Women’s Writing/Women’s Work in Early Modernity/2014 English Department/University of Texas, Arlington Philippe Mornay, Mary Sidney, and the Politics of Translation Elizabeth Pentland York University It is enough that we constantly and continually waite for her comming, that shee may neuer finde vs vnprouided. For as there is nothing more certaine then death, so is there nothing more vncertaine then the houre of death, knowen onlie to God, the onlie Author of life and death, to whom wee all ought endeuour both to liue and die. Die to liue, Liue to die.1 In 1592, Mary Sidney published in a single volume her translations of A Discourse of Life and Death. Written in French by Ph. Mornay and Antonius, a Tragœdie written also in French by Ro. Garnier. Although she may initially have undertaken the work for personal reasons, as she mourned the death of her brother, Philip, her decision to publish the translations, some two years after she completed them, 67 was motivated by recent events at court. Criticism of Mary Sidney’s works has long been interested in the political dimension of her work, but scholars have only recently begun to explore more fully the transnational contexts for her literary activity.2 Much of that scholarship has focused on her translation of Garnier’s Marc Antoine. In this essay, I look at the early history of Philippe du Plessis Mornay’s text, originally titled the Excellent discovrs de la vie et de la mort, in order to suggest not only what the work meant for its author when he wrote it in the mid-1570s, but also what additional significance it had accrued for Mary Sidney by the time she published her translation of it in 1592. -

H. Doc. 108-222

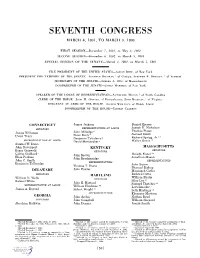

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Chester County Deed Book Index 1681-1865

Chester County Deed Book Index 1681-1865 Buyer/Seller Last First Middle Sfx/Pfx Spouse Residence Misc Property Location Village/Tract Other Party Year Book Page Instrument Comments Seller (Grantor) Wayne Michael Elizabeth East Whiteland et. al. East Whiteland John Knugie 1772 T 147 Deed Seller (Grantor) Wayne Rebecca et. al. East & West Joseph B. Jacobs, 1833 H-4 154 Release Whiteland, et.al. Charlestown Seller (Grantor) Wayne Ruth Anna et. al. East & West Joseph B. Jacobs, 1833 H-4 154 Release Whiteland, et.al. Charlestown Seller (Grantor) Wayne William Rebecca Potts, Philadelphia et. al. East & West Joseph B. Jacobs, 1833 H-4 154 Release dec'd Whiteland, et.al. Charlestown Buyer (Grantee) Weadley William Philadelphia Tredyffrin Isaac W. Holstein 1859 W-6 224 Deed Seller (Grantor) Wear Agness Upper Oxford et. al. Upper Oxford Benjamin Vanfossen 1799 S-2 315 Release Seller (Grantor) Weasner John Mary (late Douglass, Berks County et. al. East Nantmeal John Neiman 1823 Y-4 194 Deed Yocum) Buyer (Grantee) Weatherby Benjamin Marple Easttown Isaac Minshall 1758 L 142 Mortgage Buyer (Grantee) Weatherby Benjamin Tredyffrin Tredyffrin Enoch James 1762 X 365 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Weatherby Benjamin Tredyffrin et. al. Tredyffrin Lewis Davids 1762 X 364 Deed Buyer (Grantee) Weatherby Benjamin Tredyffrin Easttown Thomas Henderson 1762 D-2 152 Deed Seller (Grantor) Weatherby Benjamin Hannah Easttown Charles Norris 1763 N 207 Mortgage Seller (Grantor) Weatherby Benjamin Hannah Tredyffrin Tredyffrin Whitehead 1763 X 366 Deed Weatherby Chester County -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

H. Doc. 108-222

Biographies 995 Relations, 1959-1973; elected as a Republican to the Eighty- ty in 1775; retired from public life in 1793; died in fifth and to the seven succeeding Congresses (January 3, Windham, Conn., May 13, 1807; interment in Windham 1957-January 3, 1973); was not a candidate for reelection Cemetery. in 1972 to the Ninety-third Congress; retired and resided Bibliography: Willingham, William F. Connecticut Revolutionary: in Elizabeth, N.J., where she died February 29, 1976; inter- Eliphalet Dyer. Hartford: American Revolutionary Bicentennial Commission ment in St. Gertrude’s Cemetery, Colonia, N.J. of Connecticut, 1977. DYAL, Kenneth Warren, a Representative from Cali- DYER, Leonidas Carstarphen (nephew of David Patter- fornia; born in Bisbee, Cochise County, Ariz., July 9, 1910; son Dyer), a Representative from Missouri; born near attended the public schools of San Bernardino and Colton, Warrenton, Warren County, Mo., June 11, 1871; attended Calif.; moved to San Bernardino, Calif., in 1917; secretary the common schools, Central Wesleyan College, Warrenton, to San Bernardino, County Board of Supervisors, 1941-1943; Mo., and Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.; studied served as a lieutenant commander in the United States law; was admitted to the bar in 1893 and commenced prac- Naval Reserve, 1943-1946; postmaster of San Bernardino, tice in St. Louis, Mo.; served in the Spanish-American War; 1947-1954; insurance company executive, 1954-1961; mem- was a member of the staff of Governor Hadley of Missouri, ber of board of directors