Lecture 1: Proofs and Logic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINEAR ALGEBRA METHODS in COMBINATORICS László Babai

LINEAR ALGEBRA METHODS IN COMBINATORICS L´aszl´oBabai and P´eterFrankl Version 2.1∗ March 2020 ||||| ∗ Slight update of Version 2, 1992. ||||||||||||||||||||||| 1 c L´aszl´oBabai and P´eterFrankl. 1988, 1992, 2020. Preface Due perhaps to a recognition of the wide applicability of their elementary concepts and techniques, both combinatorics and linear algebra have gained increased representation in college mathematics curricula in recent decades. The combinatorial nature of the determinant expansion (and the related difficulty in teaching it) may hint at the plausibility of some link between the two areas. A more profound connection, the use of determinants in combinatorial enumeration goes back at least to the work of Kirchhoff in the middle of the 19th century on counting spanning trees in an electrical network. It is much less known, however, that quite apart from the theory of determinants, the elements of the theory of linear spaces has found striking applications to the theory of families of finite sets. With a mere knowledge of the concept of linear independence, unexpected connections can be made between algebra and combinatorics, thus greatly enhancing the impact of each subject on the student's perception of beauty and sense of coherence in mathematics. If these adjectives seem inflated, the reader is kindly invited to open the first chapter of the book, read the first page to the point where the first result is stated (\No more than 32 clubs can be formed in Oddtown"), and try to prove it before reading on. (The effect would, of course, be magnified if the title of this volume did not give away where to look for clues.) What we have said so far may suggest that the best place to present this material is a mathematics enhancement program for motivated high school students. -

UNIT-I Mathematical Logic Statements and Notations

UNIT-I Mathematical Logic Statements and notations: A proposition or statement is a declarative sentence that is either true or false (but not both). For instance, the following are propositions: “Paris is in France” (true), “London is in Denmark” (false), “2 < 4” (true), “4 = 7 (false)”. However the following are not propositions: “what is your name?” (this is a question), “do your homework” (this is a command), “this sentence is false” (neither true nor false), “x is an even number” (it depends on what x represents), “Socrates” (it is not even a sentence). The truth or falsehood of a proposition is called its truth value. Connectives: Connectives are used for making compound propositions. The main ones are the following (p and q represent given propositions): Name Represented Meaning Negation ¬p “not p” Conjunction p q “p and q” Disjunction p q “p or q (or both)” Exclusive Or p q “either p or q, but not both” Implication p ⊕ q “if p then q” Biconditional p q “p if and only if q” Truth Tables: Logical identity Logical identity is an operation on one logical value, typically the value of a proposition that produces a value of true if its operand is true and a value of false if its operand is false. The truth table for the logical identity operator is as follows: Logical Identity p p T T F F Logical negation Logical negation is an operation on one logical value, typically the value of a proposition that produces a value of true if its operand is false and a value of false if its operand is true. -

CSE Yet, Please Do Well! Logical Connectives

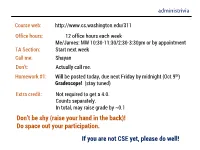

administrivia Course web: http://www.cs.washington.edu/311 Office hours: 12 office hours each week Me/James: MW 10:30-11:30/2:30-3:30pm or by appointment TA Section: Start next week Call me: Shayan Don’t: Actually call me. Homework #1: Will be posted today, due next Friday by midnight (Oct 9th) Gradescope! (stay tuned) Extra credit: Not required to get a 4.0. Counts separately. In total, may raise grade by ~0.1 Don’t be shy (raise your hand in the back)! Do space out your participation. If you are not CSE yet, please do well! logical connectives p q p q p p T T T T F T F F F T F T F NOT F F F AND p q p q p q p q T T T T T F T F T T F T F T T F T T F F F F F F OR XOR 푝 → 푞 • “If p, then q” is a promise: p q p q F F T • Whenever p is true, then q is true F T T • Ask “has the promise been broken” T F F T T T If it’s raining, then I have my umbrella. related implications • Implication: p q • Converse: q p • Contrapositive: q p • Inverse: p q How do these relate to each other? How to see this? 푝 ↔ 푞 • p iff q • p is equivalent to q • p implies q and q implies p p q p q Let’s think about fruits A fruit is an apple only if it is either red or green and a fruit is not red and green. -

Conditional Statement/Implication Converse and Contrapositive

Conditional Statement/Implication CSCI 1900 Discrete Structures •"ifp then q" • Denoted p ⇒ q – p is called the antecedent or hypothesis Conditional Statements – q is called the consequent or conclusion Reading: Kolman, Section 2.2 • Example: – p: I am hungry q: I will eat – p: It is snowing q: 3+5 = 8 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 1 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 2 Conditional Statement/Implication Truth Table Representing Implication (continued) • In English, we would assume a cause- • If viewed as a logic operation, p ⇒ q can only be and-effect relationship, i.e., the fact that p evaluated as false if p is true and q is false is true would force q to be true. • This does not say that p causes q • If “it is snowing,” then “3+5=8” is • Truth table meaningless in this regard since p has no p q p ⇒ q effect at all on q T T T • At this point it may be easiest to view the T F F operator “⇒” as a logic operationsimilar to F T T AND or OR (conjunction or disjunction). F F T CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 3 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 4 Examples where p ⇒ q is viewed Converse and contrapositive as a logic operation •Ifp is false, then any q supports p ⇒ q is • The converse of p ⇒ q is the implication true. that q ⇒ p – False ⇒ True = True • The contrapositive of p ⇒ q is the –False⇒ False = True implication that ~q ⇒ ~p • If “2+2=5” then “I am the king of England” is true CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 5 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 6 1 Converse and Contrapositive Equivalence or biconditional Example Example: What is the converse and •Ifp and q are statements, the compound contrapositive of p: "it is raining" and q: I statement p if and only if q is called an get wet? equivalence or biconditional – Implication: If it is raining, then I get wet. -

Logical Connectives Good Problems: March 25, 2008

Logical Connectives Good Problems: March 25, 2008 Mathematics has its own language. As with any language, effective communication depends on logically connecting components. Even the simplest “real” mathematical problems require at least a small amount of reasoning, so it is very important that you develop a feeling for formal (mathematical) logic. Consider, for example, the two sentences “There are 10 people waiting for the bus” and “The bus is late.” What, if anything, is the logical connection between these two sentences? Does one logically imply the other? Similarly, the two mathematical statements “r2 + r − 2 = 0” and “r = 1 or r = −2” need to be connected, otherwise they are merely two random statements that convey no useful information. Warning: when mathematicians talk about implication, it means that one thing must be true as a consequence of another; not that it can be true, or might be true sometimes. Words and symbols that tie statements together logically are called logical connectives. They allow you to communicate the reasoning that has led you to your conclusion. Possibly the most important of these is implication — the idea that the next statement is a logical consequence of the previous one. This concept can be conveyed by the use of words such as: therefore, hence, and so, thus, since, if . then . , this implies, etc. In the middle of mathematical calculations, we can represent these by the implication symbol (⇒). For example 3 − x x + 7y2 = 3 ⇒ y = ± ; (1) r 7 x ∈ (0, ∞) ⇒ cos(x) ∈ [−1, 1]. (2) Converse Note that “statement A ⇒ statement B” does not necessarily mean that the logical converse — “statement B ⇒ statement A” — is also true. -

2-2 Statements, Conditionals, and Biconditionals

2-2 Statements, Conditionals, and Biconditionals Use the following statements to write a 3. compound statement for each conjunction or SOLUTION: disjunction. Then find its truth value. Explain your reasoning. is a disjunction. A disjunction is true if at least p: A week has seven days. one of the statements is true. q is false, since there q: There are 20 hours in a day. are 24 hours in a day, not 20 hours. r is true since r: There are 60 minutes in an hour. there are 60 minutes in an hour. Thus, is true, 1. p and r because r is true. SOLUTION: ANSWER: p and r is a conjunction. A conjunction is true only There are 20 hours in a day, or there are 60 minutes when both statements that form it are true. p is true in an hour. since a week has seven day. r is true since there are is true, because r is true. 60 minutes in an hour. Then p and r is true, 4. because both p and r are true. SOLUTION: ANSWER: ~p is a negation of statement p, or the opposite of A week has seven days, and there are 60 minutes in statement p. The or in ~p or q indicates a an hour. p and r is true, because p is true and r is disjunction. A disjunction is true if at least one of the true. statements is true. ~p would be : A week does not have seven days, 2. which is false. q is false since there are 24 hours in SOLUTION: a day, not 20 hours in a day. -

New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 6-6-2018 New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations Muayad Jaafar Aljafar Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Aljafar, Muayad Jaafar, "New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4372. 10.15760/etd.6256 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations by Muayad Jaafar Aljafar A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical and Computer Engineering Dissertation Committee: Marek A. Perkowski, Chair John M. Acken Xiaoyu Song Steven Bleiler Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Muayad Jaafar Aljafar Abstract Over the past five decades, exponential advances in device integration in microelectronics for memory and computation applications have been observed. These advances are closely related to miniaturization in integrated circuit technologies. However, this miniaturization is reaching the physical limit (i.e., the end of Moore’s Law). This miniaturization is also causing a dramatic problem of heat dissipation in integrated circuits. Additionally, approaching the physical limit of semiconductor devices in fabrication process increases the delay of moving data between computing and memory units hence decreasing the performance. The market requirements for faster computers with lower power consumption can be addressed by new emerging technologies such as memristors. -

Reasoning with Ambiguity

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Reasoning with Ambiguity Christian Wurm the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract We treat the problem of reasoning with ambiguous propositions. Even though ambiguity is obviously problematic for reasoning, it is no less ob- vious that ambiguous propositions entail other propositions (both ambiguous and unambiguous), and are entailed by other propositions. This article gives a formal analysis of the underlying mechanisms, both from an algebraic and a logical point of view. The main result can be summarized as follows: sound (and complete) reasoning with ambiguity requires a distinction between equivalence on the one and congruence on the other side: the fact that α entails β does not imply β can be substituted for α in all contexts preserving truth. With- out this distinction, we will always run into paradoxical results. We present the (cut-free) sequent calculus ALcf , which we conjecture implements sound and complete propositional reasoning with ambiguity, and provide it with a language-theoretic semantics, where letters represent unambiguous meanings and concatenation represents ambiguity. Keywords Ambiguity, reasoning, proof theory, algebra, Computational Linguistics Acknowledgements Thanks to Timm Lichte, Roland Eibers, Roussanka Loukanova and Gerhard Schurz for helpful discussions; also I want to thank two anonymous reviewers for their many excellent remarks! 1 Introduction This article gives an extensive treatment of reasoning with ambiguity, more precisely with ambiguous propositions. We approach the problem from an Universit¨atD¨usseldorf,Germany Universit¨atsstr.1 40225 D¨usseldorf Germany E-mail: [email protected] 2 Christian Wurm algebraic and a logical perspective and show some interesting surprising results on both ends, which lead up to some interesting philosophical questions, which we address in a preliminary fashion. -

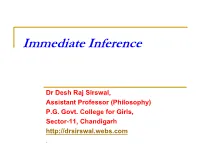

Immediate Inference

Immediate Inference Dr Desh Raj Sirswal, Assistant Professor (Philosophy) P.G. Govt. College for Girls, Sector-11, Chandigarh http://drsirswal.webs.com . Inference Inference is the act or process of deriving a conclusion based solely on what one already knows. Inference has two types: Deductive Inference and Inductive Inference. They are deductive, when we move from the general to the particular and inductive where the conclusion is wider in extent than the premises. Immediate Inference Deductive inference may be further classified as (i) Immediate Inference (ii) Mediate Inference. In immediate inference there is one and only one premise and from this sole premise conclusion is drawn. Immediate inference has two types mentioned below: Square of Opposition Eduction Here we will know about Eduction in details. Eduction The second form of Immediate Inference is Eduction. It has three types – Conversion, Obversion and Contraposition. These are not part of the square of opposition. They involve certain changes in their subject and predicate terms. The main concern is to converse logical equivalence. Details are given below: Conversion An inference formed by interchanging the subject and predicate terms of a categorical proposition. Not all conversions are valid. Conversion grounds an immediate inference for both E and I propositions That is, the converse of any E or I proposition is true if and only if the original proposition was true. Thus, in each of the pairs noted as examples either both propositions are true or both are false. Steps for Conversion Reversing the subject and the predicate terms in the premise. Valid Conversions Convertend Converse A: All S is P. -

A Computer-Verified Monadic Functional Implementation of the Integral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Theoretical Computer Science 411 (2010) 3386–3402 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Theoretical Computer Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tcs A computer-verified monadic functional implementation of the integral Russell O'Connor, Bas Spitters ∗ Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We provide a computer-verified exact monadic functional implementation of the Riemann Received 10 September 2008 integral in type theory. Together with previous work by O'Connor, this may be seen as Received in revised form 13 January 2010 the beginning of the realization of Bishop's vision to use constructive mathematics as a Accepted 23 May 2010 programming language for exact analysis. Communicated by G.D. Plotkin ' 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Type theory Functional programming Exact real analysis Monads 1. Introduction Integration is one of the fundamental techniques in numerical computation. However, its implementation using floating- point numbers requires continuous effort on the part of the user in order to ensure that the results are correct. This burden can be shifted away from the end-user by providing a library of exact analysis in which the computer handles the error estimates. For high assurance we use computer-verified proofs that the implementation is actually correct; see [21] for an overview. It has long been suggested that, by using constructive mathematics, exact analysis and provable correctness can be unified [7,8]. Constructive mathematics provides a high-level framework for specifying computations (Section 2.1). -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Propositions as Types Citation for published version: Wadler, P 2015, 'Propositions as Types', Communications of the ACM, vol. 58, no. 12, pp. 75-84. https://doi.org/10.1145/2699407 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1145/2699407 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Communications of the ACM General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Propositions as Types ∗ Philip Wadler University of Edinburgh [email protected] 1. Introduction cluding Agda, Automath, Coq, Epigram, F#,F?, Haskell, LF, ML, Powerful insights arise from linking two fields of study previously NuPRL, Scala, Singularity, and Trellys. thought separate. Examples include Descartes’s coordinates, which Propositions as Types is a notion with mystery. Why should it links geometry to algebra, Planck’s Quantum Theory, which links be the case that intuitionistic natural deduction, as developed by particles to waves, and Shannon’s Information Theory, which links Gentzen in the 1930s, and simply-typed lambda calculus, as devel- thermodynamics to communication. -

Introduction to Logic CIS008-2 Logic and Foundations of Mathematics

Introduction to Logic CIS008-2 Logic and Foundations of Mathematics David Goodwin [email protected] 11:00, Tuesday 15th Novemeber 2011 Outline 1 Propositions 2 Conditional Propositions 3 Logical Equivalence Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence The Wire \If you play with dirt you get dirty." Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence True or False? 1 The only positive integers that divide 7 are 1 and 7 itself. 2 For every positive integer n, there is a prime number larger than n. 3 x + 4 = 6. 4 Write a pseudo-code to solve a linear diophantine equation. Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence True or False? 1 The only positive integers that divide 7 are 1 and 7 itself. True. 2 For every positive integer n, there is a prime number larger than n. True 3 x + 4 = 6. The truth depends on the value of x. 4 Write a pseudo-code to solve a linear diophantine equation. Neither true or false. Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence Propositions A sentence that is either true or false, but not both, is called a proposition. The following two are propositions 1 The only positive integers that divide 7 are 1 and 7 itself. True. 2 For every positive integer n, there is a prime number larger than n. True whereas the following are not propositions 3 x + 4 = 6. The truth depends on the value of x. 4 Write a pseudo-code to solve a linear diophantine equation. Neither true or false. Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence Notation We will use the notation p : 2 + 2 = 5 to define p to be the proposition 2 + 2 = 5.