Rila Mukherjee1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Sediment Dispersal Process and Its Management in the Meghna

Sediment Problems and Sediment Management in Asian River Basins 203 (Proceedings of the Workshop held at Hyderabad, India, September 2009). IAHS Publ. 349, 2011. Sediment dispersal processes and management in coping with climate change in the Meghna Estuary, Bangladesh MAMINUL HAQUE SARKER, JAKIA AKTER, MD RUKNUL FERDOUS & FAHMIDA NOOR Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), House no.6, Road no. 23/C, Gulshan-1, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh [email protected] Abstract Due to flat terrain and dense population, the Bengal Delta is highly vulnerable to sea level rise. At present the delta building process is active in the Meghna Estuary. Information on sediment dispersal processes in the estuary and their response to different exogenic and anthropogenic forces is an important requirement for managing the sediment and developing adaptive measures to counter the potential impact of climate change. Historical maps, satellite images and tidal water level data were analysed and the response of the Meghna Estuary to extreme events, e.g. the 1950 Assam earthquake, as well as anthropogenic interventions, was assessed. The issue of sediment management was addressed, based on an understanding of the response of the estuary to the extreme natural event and anthropogenic interventions, along with an assessment of the response of the estuary to sea level rise. Among other interventions, emphasis has been directed to promoting vertical accretion by injecting sediment into polders. Key words Bengal delta; Meghna Estuary; sea level rise; sediment dispersal processes; vertical accretion; sediment injection INTRODUCTION Deltas are a large accumulation of both fluvial and marine sediments which have infilled river mouths and extended onto the continental shelf (Fookes et al., 2007). -

Cyclone Disaster Vulnerability and Response Experiences in Coastal

Cyclone disaster vulnerability and response experiences in coastal Bangladesh Edris Alam Assistant Professor and Disaster and Development Centre Affiliate, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Chittagong, Bangladesh and Andrew E. Collins Reader in Disaster and Development, Disaster and Development Centre, School of Applied Sciences, Northumbria University, United Kingdom For generations, cyclones and tidal surges have frequently devastated lives and property in coastal and island Bangladesh. This study explores vulnerability to cyclone hazards using first-hand coping recollections from prior to, during and after these events. Qualitative field data suggest that, beyond extreme cyclone forces, localised vulnerability is defined in terms of response processes, infrastructure, socially uneven exposure, settlement development patterns, and livelihoods. Prior to cyclones, religious activities increase and people try to save food and valuable possessions. Those in dispersed settlements who fail to reach cyclone shelters take refuge in thatched-roof houses and big-branch trees. However, women and children are affected more despite the modification of traditional hierarchies during cyclone periods. Instinctive survival strategies and intra-community cooperation improve coping post cyclone. This study recommends that disaster reduction programmes encourage cyclone mitigation while being aware of localised realities, endogenous risk analyses, and coping and adaptation of affected communities (as active survivors rather than helpless victims). Keywords: coastal and island people of Bangladesh, coping, cyclone vulnerability, local response Introduction With the effects of natural hazards rising in terms of loss of life and injuries in poorer nations (ISDR, 2002; World Bank, 2005; CRED, 2007), institutional disaster reduction approaches (ISDR, 2004; UNDP, 2004; DFID, 2005) and approaches adaptable to individual social and livelihood experiences are required. -

Role of Bengali Women in the Freedom Movement Abstract

Heteroglossia: A Multidisciplinary Research Journal June 2016 | Vol. 01 | No. 01 Role of Bengali Women in the Freedom Movement Kasturi Roy Chatterjee1 Abstract In India women is always affected by the lack of opportunities and facilities. This is due to innate discrimination prevalent within the society for years. Thus when the role of Bengali women in the freedom movement is considered one faces a lot of difficulty, as because the women whatever their role were never highlighted. But in recent years however it is being pointed out that Bengali women not only participated in the freedom movement but had played an active role in it. KeyWords: Swadeshi, Boycott, catalysts, Patriarchy, Civil Disobidience, Satyagraha, Quit India. 1 Assistant Professor in History, Sundarban Mahavidyalaya, Kakdwip, South 24 Parganas, Pin-743347 49 Heteroglossia: A Multidisciplinary Research Journal June 2016 | Vol. 01 | No. 01 Introduction: In attempting to analyse the role of Bengali women in the Indian Freedom Struggle, one faces a series of problem is at the very outset. There are very few comprehensive studies on women’s participation in the freedom movement. In my paper I will try to bring forward a complete picture of Bengali women’s active role in the politics of protest: Bengal from 1905-1947, which is so far being discussed in different phases. In this way we can explain that how the women from time to time had strengthened the nationalist movement not only in the way it is shaped for them but once they participated they had mobilized the movement in their own way. Nature of Participatation in the Various Movements: A general idea for quite a long time had circulated regarding women’s participation that it is male dictated. -

Chapter-I Historical Growth of Barasat Town

CHAPTER-I HISTORICAL GROWTH OF BARASAT TOWN INTRODUCTION: 'God made !the country and man made the town' - so says a proverb. Towns are created out of the necessities created by man also. For administrative reasons, for trade and commerce, and for many other obvious reasons, towns/cities emerge. Sometimes there are accidents of history (e.g. Calcutta), sometimes there are planning behind (e.g. Kalyani at Nadia District, West Bengal, Durgapur at Barddhaman District, West Bengal). The present investigation centres around a small township, which grew out of a tiny hamlet into a district town with all the characteristics associated with the process of urbanisation. The tiny hamlet expanded, attracted people from all around and developed into an administrative centre. Advantages of natural growth are no substitute for meticulous planning for tackling with the attendant problem of urbanisation. 1.1 PRE BRITISH PERIOD: The term 'Barasat' means 'Avenue'. Both sides of the road were planted with trees, Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of Bengal (1774-84), planted trees on both sides of the road. Pandit Haraprasad Shastri, a noted lndologist, was of the view that the name 'Barasat originated from the concept that on both sides of the road planted trees were in abundance. Other evidences are not lacking which prove that its history extends to the middle ages. Twelve members of the family of Jagat Sett, the banker of the Nawab of Bengal, lived here. Settpukur and other villages after their names are still there. Another Sett, Ramchandra, a descendant of Jagat Sett, dug out a tank near the Jessore Road to please Hastings. -

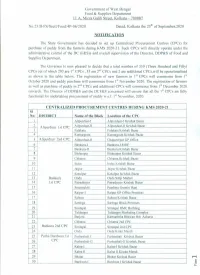

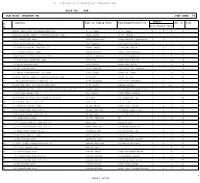

Notification on CPC.Pdf

Government of West Bengal Food & Supplies Department 11 A, Mirza Galib Street, Kolkata - 700087 No.2318-FS/Sectt/Food/4P-06/2020 Dated, Kolkata the zs" of September,2020 NOTIFICATION The State Government has decided to set up Centralized Procurement Centres (CPCs) for purchase of paddy from the farmers during KMS 2020-21. Such CPCs will directly operate under the administrative control of the DC (F&S)s and overall supervision of the Director, DDP&S of Food and Supplies Department. The Governor is now pleased to decide that a total number of 350 (Three Hundred and Fifty) nd CPCs out of which 293 are 1st CPCs ,55 are 2 CPCs and 2 are additional CPCs,will be operationalised as shown in the table below. The registration of new farmers in 1st CPCs will commence from 1sI October 2020 and paddy purchase will commence from 1st November 2020. The registration of farmers nd as well as purchase of paddy in 2 CPCs and additional CPCs will commence from 1st December 2020 onwards. The Director of DDP&S and the DCF&S concerned will ensure that all the 1st CPCs are fully functional for undertaking procurement of paddy w.e.f. 1st November, 2020. CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT CENTRES DURING KMS 2020-21 SI No: DISTRICT Name ofthe Block Location of the CPC f--- 1 Alipurduar-I Alipurduar-I Krishak Bazar 2 Alipurduar-II Alipurduar-II Krishak Bazar f--- Alipurduar 1st CPC - 3 Falakata Falakata Krishak Bazar 4 Kurnarzram Kumarzram Krishak Bazar 5 Alipurduar 2nd Cf'C Alipurduar-Il Chaporerpar GP Office - 6 Bankura-l Bankura-I RlDF f--- 7 Bankura-II Bankura Krishak Bazar I--- 8 Bishnupur Bishnupur Krishak Bazar I--- 9 Chhatna Chhatna Krishak Bazar 10 - Indus Indus Krishak Bazar ..». -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Changing Meaning Of, , – Aboriginal Groups

INDEX Abhijat, – M. Monier-William’s views on, changing meaning of, , – negative assessments of, Aboriginal groups, Orientalist lineages of, , differentiation from ‘Aryan’ racial and sociological literati, connotations, , exclusion of, valour, , Academic Association, valour, in regional context of Adivasis, , , , –, Bengal, – –, virtual, , Hinduisation of, Asiatic Society, Aitihasik Chitra, and history-writing, agenda of, Atmiyata, and Indian history, – among unrelated individuals, and Rabindranath Tagore, as welding people of the samaj, circulation, , Anderson, Benedict, – Atmiya sajan, and role of print-capitalism, difference between role of print in Bagal, Jogeshchandra, European nationalism and in Bandyopadhyay, Krishnamohan, Bengal, Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, Anglo-vernacular schools, and variations of caste rank in Aryan, Bengal, as culture, , and ‘low’ caste protest as race, movements, as racial categories, Bangiya Sahitya Parishat, Bengali-Aryan connection, , Romeshchandra Datta as its first , , –, chairman, Bengali-Hindu connection, , Bar Bhuiyans, , – , Basanta Ray, , colonial disjunction of, from Kedar Ray, , , non-Aryan groups, , Pratapaditya, , , , , dharma, differences from non-Aryan, Barth, Frederik difference from non-Aryan in and ethnic boundaries, Bengali discourse, Basu, Nagendranath, , , early samaj, , , and fieldwork undertaken to equated with ‘Hindu’, , reconstruct samajik itihas, idea, emphasis on kulagranthas, India, –, , , , – on caste, index on Dashinrarhiya Kayastha -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Ward No

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 088 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 MATHOR PARA ROAD 94 TALLYGUNGE ROAD A. P. HELA R. L. HELA 2 5 7 1 2 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ABHA SARKAR SUSIL SARKAR 2 1 3 2 3 100 TALLYGUNGE ROAD ACHO CHAKHALIYA LATE KRISHNA CHAKHALIYA 2 4 6 3 4 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ADAR MONDAL LATE MATHUN MONDAL 0 1 1 4 5 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE KOL 26 ADHIR GHOSH LT AKSHAY GHOSH 2 4 6 5 6 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ADHIR MONDAL LATE DURGA MONDAL 1 0 1 6 7 19A PRATAP ADITYA PLACE KOL-26 ADHIR PRAMANICK LT UPEN PRAMANICK 3 2 5 7 8 11/1/M GOPAL BANERJEE LANE AJAY DAS LATE LALIT KR.DAS 2 2 4 8 9 13 BAULI MONDAL ROAD AJAY GHOSH LATE ANIL GHOSH 3 1 4 9 10 54 TALLYGUNGE ROAD AJAY SAMANTA LATE MITHILAL SAMANTA 2 2 4 10 11 37 NEPAL BHATTACHARYA 1ST LANE AJAY SINGH LATE LOK SINGH 3 1 4 11 12 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE AJIT DAS LT K. L. DAS 3 1 4 12 13 16A CHANDRA MONDAL LANE KOL-26 AJIT KARMAKAR LT SUDHIR KARMAKAR 4 3 7 14 14 TALLYGUNGE ROAD 108 TALLYGUNGE ROAD AJOY PRASD RAMDEB PRASAD 7 6 10+ 15 15 S.P. MUKHERJEE ROAD 200H S.P. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOL-26 ALAOK BOSE LT. -

Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1955 Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys. S. Ali ibne hamid Rizvi Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Rizvi, S. Ali ibne hamid, "Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys." (1955). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 109. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/109 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE PHYSIOGRAPHY OF THE LOWER GANGES AND LOWER MISSISSIPPI VALLEYS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography ^ by 9. Ali IJt**Hr Rizvi B*. A., Muslim University, l9Mf M. A*, Muslim University, 191*6 M. A., Muslim University, 191*6 May, 1955 EXAMINATION AND THESIS REPORT Candidate: ^ A li X. H. R iz v i Major Field: G eography Title of Thesis: Comparison Between Lower Mississippi and Lower Ganges* Brahmaputra Valleys Approved: Major Prj for And Chairman Dean of Gri ualc School EXAMINING COMMITTEE: 2m ----------- - m t o R ^ / q Date of Examination: ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to tender his sincere gratitude to Dr. Richard J. Russell for his direction and supervision of the work at every stage; to Dr.