Stellar Black Holes in Globular Clusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Star Newsletter

THE HOT STAR NEWSLETTER ? An electronic publication dedicated to A, B, O, Of, LBV and Wolf-Rayet stars and related phenomena in galaxies ? No. 70 2002 July-August http://www.astro.ugto.mx/∼eenens/hot/ editor: Philippe Eenens http://www.star.ucl.ac.uk/∼hsn/index.html [email protected] ftp://saturn.sron.nl/pub/karelh/uploads/wrbib/ Contents of this newsletter Call for Data . 1 Abstracts of 12 accepted papers . 2 Abstracts of 2 submitted papers . 10 Abstracts of 6 proceedings papers . 11 Jobs .......................................................................13 Meetings ...................................................................14 Call for Data The multiplicity of 9 Sgr G. Rauw and H. Sana Institut d’Astrophysique, Universit´ede Li`ege,All´eedu 6 Aoˆut, BˆatB5c, B-4000 Li`ege(Sart Tilman), Belgium e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] The non-thermal radio emission observed for a number of O and WR stars implies the presence of a small population of relativistic electrons in the winds of these objects. Electrons could be accelerated to relativistic velocities either in the shock region of a colliding wind binary (Eichler & Usov 1993, ApJ 402, 271) or in the shocks due to intrinsic wind instabilities of a single star (Chen & White 1994, Ap&SS 221, 259). Dougherty & Williams (2000, MNRAS 319, 1005) pointed out that 7 out of 9 WR stars with non-thermal radio emission are in fact binary systems. This result clearly supports the colliding wind scenario. In the present issue of the Hot Star Newsletter, we announce the results of a multi-wavelength campaign on the O4 V star 9 Sgr (= HD 164794; see the abstract by Rauw et al.). -

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science Corresponding Authors Lucianne M. Walkowicz Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley [email protected] phone: (510) 642–6931 Andrew C. Becker Department of Astronomy, University of Washington [email protected] phone: (206) 685–0542 Authors Scott F. Anderson, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Joshua S. Bloom, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Leonid Georgiev, Universidad Autonoma de Mexico Josh Grindlay, Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Steve Howell, National Optical Astronomy Observatory Knox Long, Space Telescope Science Institute Anjum Mukadam, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Andrej Prsa,ˇ Villanova University Joshua Pepper, Villanova University Arne Rau, California Institute of Technology Branimir Sesar, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nicole Silvestri, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nathan Smith, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Keivan Stassun, Vanderbilt University Paula Szkody, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Science Frontier Panels: Stars and Stellar Evolution (SSE) February 16, 2009 Abstract The next decade of survey astronomy has the potential to transform our knowledge of variable stars. Stellar variability underpins our knowledge of the cosmological distance ladder, and provides direct tests of stellar formation and evolution theory. Variable stars can also be used to probe the fundamental physics of gravity and degenerate material in ways that are otherwise impossible in the laboratory. The computational and engineering advances of the past decade have made large–scale, time–domain surveys an immediate reality. Some surveys proposed for the next decade promise to gather more data than in the prior cumulative history of astronomy. -

PSR J1740-3052: a Pulsar with a Massive Companion

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications Physics 2001 PSR J1740-3052: a Pulsar with a Massive Companion I. H. Stairs R. N. Manchester A. G. Lyne V. M. Kaspi Fronefield Crawford Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/physics_facpubs Repository Citation "PSR J1740-3052: a Pulsar with a Massive Companion" I. H. Stairs, R. N. Manchester, A. G. Lyne, V. M. Kaspi, F. Camilo, J. F. Bell, N. D'Amico, M. Kramer, F. Crawford, D. J. Morris, A. Possenti, N. P. F. McKay, S. L. Lumsden, L. E. Tacconi-Garman, R. D. Cannon, N. C. Hambly, & P. R. Wood, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 325, 979 (2001). This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 325, 979–988 (2001) PSR J174023052: a pulsar with a massive companion I. H. Stairs,1,2P R. N. Manchester,3 A. G. Lyne,1 V. M. Kaspi,4† F. Camilo,5 J. F. Bell,3 N. D’Amico,6,7 M. Kramer,1 F. Crawford,8‡ D. J. Morris,1 A. Possenti,6 N. P. F. McKay,1 S. L. Lumsden,9 L. E. Tacconi-Garman,10 R. D. Cannon,11 N. C. Hambly12 and P. R. Wood13 1University of Manchester, Jodrell Bank Observatory, Macclesfield, Cheshire SK11 9DL 2National Radio Astronomy Observatory, PO Box 2, Green Bank, WV 24944, USA 3Australia Telescope National Facility, CSIRO, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 4Physics Department, McGill University, 3600 University Street, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 2T8, Canada 5Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, Columbia University, 550 W. -

SXP 1062, a Young Be X-Ray Binary Pulsar with Long Spin Period⋆

A&A 537, L1 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118369 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor SXP 1062, a young Be X-ray binary pulsar with long spin period Implications for the neutron star birth spin F. Haberl1, R. Sturm1, M. D. Filipovic´2,W.Pietsch1, and E. J. Crawford2 1 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße, 85748 Garching, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith South DC, NSW1797, Australia Received 31 October 2011 / Accepted 1 December 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) is ideally suited to investigating the recent star formation history from X-ray source population studies. It harbours a large number of Be/X-ray binaries (Be stars with an accreting neutron star as companion), and the supernova remnants can be easily resolved with imaging X-ray instruments. Aims. We search for new supernova remnants in the SMC and in particular for composite remnants with a central X-ray source. Methods. We study the morphology of newly found candidate supernova remnants using radio, optical and X-ray images and inves- tigate their X-ray spectra. Results. Here we report on the discovery of the new supernova remnant around the recently discovered Be/X-ray binary pulsar CXO J012745.97−733256.5 = SXP 1062 in radio and X-ray images. The Be/X-ray binary system is found near the centre of the supernova remnant, which is located at the outer edge of the eastern wing of the SMC. The remnant is oxygen-rich, indicating that it developed from a type Ib event. -

Origin and Binary Evolution of Millisecond Pulsars

Origin and binary evolution of millisecond pulsars Francesca D’Antona and Marco Tailo Abstract We summarize the channels formation of neutron stars (NS) in single or binary evolution and the classic recycling scenario by which mass accretion by a donor companion accelerates old NS to millisecond pulsars (MSP). We consider the possible explanations and requirements for the high frequency of the MSP population in Globular Clusters. Basics of binary evolution are given, and the key concepts of systemic angular momentum losses are first discussed in the framework of the secular evolution of Cataclysmic Binaries. MSP binaries with compact companions represent end-points of previous evolution. In the class of systems characterized by short orbital period %orb and low companion mass we may instead be catching the recycling phase ‘in the act’. These systems are in fact either MSP, or low mass X–ray binaries (LMXB), some of which accreting X–ray MSP (AMXP), or even ‘transitional’ systems from the accreting to the radio MSP stage. The donor structure is affected by irradiation due to X–rays from the accreting NS, or by the high fraction of MSP rotational energy loss emitted in the W rays range of the energy spectrum. X– ray irradiation leads to cyclic LMXB stages, causing super–Eddington mass transfer rates during the first phases of the companion evolution, and, possibly coupled with the angular momentum carried away by the non–accreted matter, helps to explain ¤ the high positive %orb’s of some LMXB systems and account for the (apparently) different birthrates of LMXB and MSP. Irradiation by the MSP may be able to drive the donor to a stage in which either radio-ejection (in the redbacks) or mass loss due to the companion expansion, and ‘evaporation’ may govern the evolution to the black widow stage and to the final disruption of the companion. -

Gravity Tests with Radio Pulsars

universe Review Gravity Tests with Radio Pulsars Norbert Wex 1,* and Michael Kramer 1,2 1 Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, D-53121 Bonn, Germany; [email protected] 2 Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 August 2020; Accepted: 17 September 2020; Published: 22 September 2020 Abstract: The discovery of the first binary pulsar in 1974 has opened up a completely new field of experimental gravity. In numerous important ways, pulsars have taken precision gravity tests quantitatively and qualitatively beyond the weak-field slow-motion regime of the Solar System. Apart from the first verification of the existence of gravitational waves, binary pulsars for the first time gave us the possibility to study the dynamics of strongly self-gravitating bodies with high precision. To date there are several radio pulsars known which can be utilized for precision tests of gravity. Depending on their orbital properties and the nature of their companion, these pulsars probe various different predictions of general relativity and its alternatives in the mildly relativistic strong-field regime. In many aspects, pulsar tests are complementary to other present and upcoming gravity experiments, like gravitational-wave observatories or the Event Horizon Telescope. This review gives an introduction to gravity tests with radio pulsars and its theoretical foundations, highlights some of the most important results, and gives a brief outlook into the future of this important field of experimental gravity. Keywords: gravity; general relativity; pulsars 1. -

Radio Jets in Galaxies with Actively Accreting Black Holes: New Insights from the SDSS � Guinevere Kauffmann,1 Timothy M

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. (2008) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12752.x Radio jets in galaxies with actively accreting black holes: new insights from the SDSS Guinevere Kauffmann,1 Timothy M. Heckman2 and Philip N. Best3 1Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Astrophysik, D-85748 Garching, Germany 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 3Institute for Astronomy, Royal Observatory Edinburgh, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ Accepted 2007 November 21. Received 2007 November 13; in original form 2007 September 17 ABSTRACT In the local Universe, the majority of radio-loud active galactic nuclei (AGN) are found in massive elliptical galaxies with old stellar populations and weak or undetected emission lines. At high redshifts, however, almost all known radio AGN have strong emission lines. This paper focuses on a subset of radio AGN with emission lines (EL-RAGN) selected from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. We explore the hypothesis that these objects are local analogues of powerful high-redshift radio galaxies. The probability for a nearby radio AGN to have emission lines is a strongly decreasing function of galaxy mass and velocity dispersion and an increasing function of radio luminosity above 1025 WHz−1. Emission-line and radio luminosities are correlated, but with large dispersion. At a given radio power, radio galaxies with small black holes have higher [O III] luminosities (which we interpret as higher accretion rates) than radio galaxies with big black holes. However, if we scale the emission-line and radio luminosities by the black hole mass, we find a correlation between normalized radio power and accretion rate in Eddington units that is independent of black hole mass. -

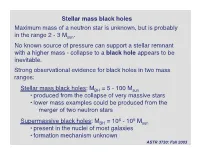

Stellar Mass Black Holes Maximum Mass of a Neutron Star Is Unknown, but Is Probably in the Range 2 - 3 Msun

Stellar mass black holes Maximum mass of a neutron star is unknown, but is probably in the range 2 - 3 Msun. No known source of pressure can support a stellar remnant with a higher mass - collapse to a black hole appears to be inevitable. Strong observational evidence for black holes in two mass ranges: Stellar mass black holes: MBH = 5 - 100 Msun • produced from the collapse of very massive stars • lower mass examples could be produced from the merger of two neutron stars 6 9 Supermassive black holes: MBH = 10 - 10 Msun • present in the nuclei of most galaxies • formation mechanism unknown ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Other types of black hole could exist too: 3 Intermediate mass black holes: MBH ~ 10 Msun • evidence for the existence of these from very luminous X-ray sources in external galaxies (L >> LEdd for a stellar mass black hole). • `more likely than not’ to exist, but still debatable Primordial black holes • formed in the early Universe • not ruled out, but there is no observational evidence and best guess is that conditions in the early Universe did not favor formation. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Basic properties of black holes Black holes are solutions to Einstein’s equations of General Relativity. Numerous theorems have been proved about them, including, most importantly: The `No-hair’ theorem A stationary black hole is uniquely characterized by its: • Mass M Conserved • Angular momentum J quantities • Charge Q Remarkable result: Black holes completely `forget’ how they were made - from stellar collapse, merger of two existing black holes etc etc… Only applies at late times. -

Stellar Evolution

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 19 www.accessscience.com Stellar evolution Contributed by: James B. Kaler Publication year: 2014 The large-scale, systematic, and irreversible changes over time of the structure and composition of a star. Types of stars Dozens of different types of stars populate the Milky Way Galaxy. The most common are main-sequence dwarfs like the Sun that fuse hydrogen into helium within their cores (the core of the Sun occupies about half its mass). Dwarfs run the full gamut of stellar masses, from perhaps as much as 200 solar masses (200 M,⊙) down to the minimum of 0.075 solar mass (beneath which the full proton-proton chain does not operate). They occupy the spectral sequence from class O (maximum effective temperature nearly 50,000 K or 90,000◦F, maximum luminosity 5 × 10,6 solar), through classes B, A, F, G, K, and M, to the new class L (2400 K or 3860◦F and under, typical luminosity below 10,−4 solar). Within the main sequence, they break into two broad groups, those under 1.3 solar masses (class F5), whose luminosities derive from the proton-proton chain, and higher-mass stars that are supported principally by the carbon cycle. Below the end of the main sequence (masses less than 0.075 M,⊙) lie the brown dwarfs that occupy half of class L and all of class T (the latter under 1400 K or 2060◦F). These shine both from gravitational energy and from fusion of their natural deuterium. Their low-mass limit is unknown. -

![Arxiv:2005.03682V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 7 May 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3341/arxiv-2005-03682v1-astro-ph-ga-7-may-2020-1373341.webp)

Arxiv:2005.03682V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 7 May 2020

Draft version May 11, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 Recovering age-metallicity distributions from integrated spectra: validation with MUSE data of a nearby nuclear star cluster Alina Boecker,1 Mayte Alfaro-Cuello,1 Nadine Neumayer,1 Ignacio Mart´ın-Navarro,1, 2, 3, 4 and Ryan Leaman1 1Max-Planck-Institut f¨urAstronomie, K¨onigstuhl17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 2Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3Departamento de Astrof´ısica, Universidad de La Laguna, E-38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 4University of California Observatories, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA (Received January 1, 2020; Revised January 7, 2020; Accepted May 11, 2020) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT Current instruments and spectral analysis programs are now able to decompose the integrated spec- trum of a stellar system into distributions of ages and metallicities. The reliability of these methods have rarely been tested on nearby systems with resolved stellar ages and metallicities. Here we derive the age-metallicity distribution of M 54, the nucleus of the Sagittarius dwarf spheroidal galaxy, from its integrated MUSE spectrum. We find a dominant old (8 14 Gyr), metal-poor (-1.5 dex) and a young (1 Gyr), metal-rich (+0:25 dex) component - consistent− with the complex stellar populations measured from individual stars in the same MUSE data set. There is excellent agreement between the (mass-weighted) average age and metallicity of the resolved and integrated analyses. Differences are only 3% in age and 0.2 dex metallicitiy. By co-adding individual stars to create M 54's integrated spectrum, we show that the recovered age-metallicity distribution is insensitive to the magnitude limit of the stars or the contribution of blue horizontal branch stars - even when including additional blue wavelength coverage from the WAGGS survey. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study.