The Evolution and Classification of Marsupials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of the Functional Morphology in the Cranial and Cervical Skeleton of the Sabre-Toothed Cat Paramachairodus Ogygia (Kaup, 1832) (Felidae

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2005? 2005 1443 363377 Original Article FUNCTIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF P. OGYGIAM. J. SALESA ET AL. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2005, 144, 363–377. With 11 figures Aspects of the functional morphology in the cranial and cervical skeleton of the sabre-toothed cat Paramachairodus ogygia (Kaup, 1832) (Felidae, Machairodontinae) from the Late Miocene of Spain: Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article-abstract/144/3/363/2627519 by guest on 18 May 2020 implications for the origins of the machairodont killing bite MANUEL J. SALESA1*, MAURICIO ANTÓN2, ALAN TURNER1 and JORGE MORALES2 1School of Biological & Earth Sciences, Byrom Street, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, L3 3AF, UK 2Departamento de Palaeobiología, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC, José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2. 28006 Madrid, Spain Received January 2004; accepted for publication March 2005 The skull and cervical anatomy of the sabre-toothed felid Paramachairodus ogygia (Kaup, 1832) is described in this paper, with special attention paid to its functional morphology. Because of the scarcity of fossil remains, the anatomy of this felid has been very poorly known. However, the recently discovered Miocene carnivore trap of Batallones-1, near Madrid, Spain, has yielded almost complete skeletons of this animal, which is now one of the best known machairodontines. Consequently, the machairodont adaptations of this primitive sabre-toothed felid can be assessed for the first time. Some characters, such as the morphology of the mastoid area, reveal an intermediate state between that of felines and machairodontines, while others, such as the flattened upper canines and verticalized mandibular symphysis, show clear machairodont affinities. -

Chronostratigraphy of the Mammal-Bearing Paleocene of South America 51

Thierry SEMPERE biblioteca Y. Joirriiol ofSoiiih Ainorirari Euirli Sciriin~r.Hit. 111. No. 1, pp. 49-70, 1997 Pergamon Q 1‘197 PublisIlcd hy Elscvicr Scicncc Ltd All rights rescrvcd. Printed in Grcnt nrilsin PII: S0895-9811(97)00005-9 0895-9X 11/97 t I7.ol) t o.(x) -. ‘Inshute qfI Human Origins, 1288 9th Street, Berkeley, California 94710, USA ’Orstom, 13 rue Geoffroy l’Angevin, 75004 Paris, France 3Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA Absfract - Land mammal faunas of Paleocene age in the southern Andean basin of Bolivia and NW Argentina are calibrated by regional sequence stratigraphy and rnagnetostratigraphy. The local fauna from Tiupampa in Bolivia is -59.0 Ma, and is thus early Late Paleocene in age. Taxa from the lower part of the Lumbrera Formation in NW Argentina (long regarded as Early Eocene) are between -58.0-55.5 Ma, and thus Late Paleocene in age. A reassessment of the ages of local faunas from lhe Rfo Chico Formation in the San Jorge basin, Patagonia, southern Argentina, shows that lhe local fauna from the Banco Negro Infeiior is -60.0 Ma, mak- ing this the most ancient Cenozoic mammal fauna in South,America. Critical reevaluation the ltaboraí fauna and associated or All geology in SE Brazil favors lhe interpretation that it accumulated during a sea-level lowsland between -$8.2-56.5 Ma. known South American Paleocene land inammal faunas are thus between 60.0 and 55.5 Ma (i.e. Late Paleocene) and are here assigned to the Riochican Land Maminal Age, with four subages (from oldest to youngest: Peligrian, Tiupampian, Ilaboraian, Riochican S.S.). -

A Dated Phylogeny of Marsupials Using a Molecular Supermatrix and Multiple Fossil Constraints

Journal of Mammalogy, 89(1):175–189, 2008 A DATED PHYLOGENY OF MARSUPIALS USING A MOLECULAR SUPERMATRIX AND MULTIPLE FOSSIL CONSTRAINTS ROBIN M. D. BECK* School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/89/1/175/1020874 by guest on 25 September 2021 Phylogenetic relationships within marsupials were investigated based on a 20.1-kilobase molecular supermatrix comprising 7 nuclear and 15 mitochondrial genes analyzed using both maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches and 3 different partitioning strategies. The study revealed that base composition bias in the 3rd codon positions of mitochondrial genes misled even the partitioned maximum-likelihood analyses, whereas Bayesian analyses were less affected. After correcting for base composition bias, monophyly of the currently recognized marsupial orders, of Australidelphia, and of a clade comprising Dasyuromorphia, Notoryctes,and Peramelemorphia, were supported strongly by both Bayesian posterior probabilities and maximum-likelihood bootstrap values. Monophyly of the Australasian marsupials, of Notoryctes þ Dasyuromorphia, and of Caenolestes þ Australidelphia were less well supported. Within Diprotodontia, Burramyidae þ Phalangeridae received relatively strong support. Divergence dates calculated using a Bayesian relaxed molecular clock and multiple age constraints suggested at least 3 independent dispersals of marsupials from North to South America during the Late Cretaceous or early Paleocene. Within the Australasian clade, the macropodine radiation, the divergence of phascogaline and dasyurine dasyurids, and the divergence of perameline and peroryctine peramelemorphians all coincided with periods of significant environmental change during the Miocene. An analysis of ‘‘unrepresented basal branch lengths’’ suggests that the fossil record is particularly poor for didelphids and most groups within the Australasian radiation. -

A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes

J Mammal Evol DOI 10.1007/s10914-007-9062-6 ORIGINAL PAPER A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes Robert W. Meredith & Michael Westerman & Judd A. Case & Mark S. Springer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Even though marsupials are taxonomically less diverse than placentals, they exhibit comparable morphological and ecological diversity. However, much of their fossil record is thought to be missing, particularly for the Australasian groups. The more than 330 living species of marsupials are grouped into three American (Didelphimorphia, Microbiotheria, and Paucituberculata) and four Australasian (Dasyuromorphia, Diprotodontia, Notoryctemorphia, and Peramelemorphia) orders. Interordinal relationships have been investigated using a wide range of methods that have often yielded contradictory results. Much of the controversy has focused on the placement of Dromiciops gliroides (Microbiotheria). Studies either support a sister-taxon relationship to a monophyletic Australasian clade or a nested position within the Australasian radiation. Familial relationships within the Diprotodontia have also proved difficult to resolve. Here, we examine higher-level marsupial relationships using a nuclear multigene molecular data set representing all living orders. Protein-coding portions of ApoB, BRCA1, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF were analyzed using maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian methods. Two different Bayesian relaxed molecular clock methods were employed to construct a timescale for marsupial evolution and estimate the unrepresented basal branch length (UBBL). Maximum likelihood and Bayesian results suggest that the root of the marsupial tree is between Didelphimorphia and all other marsupials. All methods provide strong support for the monophyly of Australidelphia. Within Australidelphia, Dromiciops is the sister-taxon to a monophyletic Australasian clade. -

Perissodactyla: Tapirus) Hints at Subtle Variations in Locomotor Ecology

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 277:1469–1485 (2016) A Three-Dimensional Morphometric Analysis of Upper Forelimb Morphology in the Enigmatic Tapir (Perissodactyla: Tapirus) Hints at Subtle Variations in Locomotor Ecology Jamie A. MacLaren1* and Sandra Nauwelaerts1,2 1Department of Biology, Universiteit Antwerpen, Building D, Campus Drie Eiken, Universiteitsplein, Wilrijk, Antwerp 2610, Belgium 2Centre for Research and Conservation, Koninklijke Maatschappij Voor Dierkunde (KMDA), Koningin Astridplein 26, Antwerp 2018, Belgium ABSTRACT Forelimb morphology is an indicator for order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates). Modern terrestrial locomotor ecology. The limb morphology of the tapirs are widely accepted to belong to a single enigmatic tapir (Perissodactyla: Tapirus) has often been genus (Tapirus), containing four extant species compared to that of basal perissodactyls, despite the lack (Hulbert, 1973; Ruiz-Garcıa et al., 1985) and sev- of quantitative studies comparing forelimb variation in eral regional subspecies (Padilla and Dowler, 1965; modern tapirs. Here, we present a quantitative assess- ment of tapir upper forelimb osteology using three- Wilson and Reeder, 2005): the Baird’s tapir (T. dimensional geometric morphometrics to test whether bairdii), lowland tapir (T. terrestris), mountain the four modern tapir species are monomorphic in their tapir (T. pinchaque), and the Malayan tapir (T. forelimb skeleton. The shape of the upper forelimb bones indicus). Extant tapirs primarily inhabit tropical across four species (T. indicus; T. bairdii; T. terrestris; T. rainforest, with some populations also occupying pinchaque) was investigated. Bones were laser scanned wet grassland and chaparral biomes (Padilla and to capture surface morphology and 3D landmark analysis Dowler, 1965; Padilla et al., 1996). was used to quantify shape. -

A Species-Level Phylogenetic Supertree of Marsupials

J. Zool., Lond. (2004) 264, 11–31 C 2004 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904005539 A species-level phylogenetic supertree of marsupials Marcel Cardillo1,2*, Olaf R. P. Bininda-Emonds3, Elizabeth Boakes1,2 and Andy Purvis1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park, Ascot SL5 7PY, U.K. 2 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, U.K. 3 Lehrstuhl fur¨ Tierzucht, Technical University of Munich, Alte Akademie 12, 85354 Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany (Accepted 26 January 2004) Abstract Comparative studies require information on phylogenetic relationships, but complete species-level phylogenetic trees of large clades are difficult to produce. One solution is to combine algorithmically many small trees into a single, larger supertree. Here we present a virtually complete, species-level phylogeny of the marsupials (Mammalia: Metatheria), built by combining 158 phylogenetic estimates published since 1980, using matrix representation with parsimony. The supertree is well resolved overall (73.7%), although resolution varies across the tree, indicating variation both in the amount of phylogenetic information available for different taxa, and the degree of conflict among phylogenetic estimates. In particular, the supertree shows poor resolution within the American marsupial taxa, reflecting a relative lack of systematic effort compared to the Australasian taxa. There are also important differences in supertrees based on source phylogenies published before 1995 and those published more recently. The supertree can be viewed as a meta-analysis of marsupial phylogenetic studies, and should be useful as a framework for phylogenetically explicit comparative studies of marsupial evolution and ecology. -

OPOSSUM Didelphis Virginiana

OPOSSUM Didelphis virginiana The Virginia opossum, Didelphis virginiana, is the only marsupial (pouched animal) native to North America. The opossum is not a native species to Vermont, but a population has become established here. The opossum is mostly active at night, being what is referred to as ‘nocturnal.’ They are very good climbers and capable swimmers. These two skills help the opossum avoid predators. It is well known for faking death (also called ‘playing possum’) as another means of outwitting its enemies. The opossum adapts to a wide variety of habitats which has led to its widespread distribution throughout the United States. Vermont Wildlife Fact Sheet Physical Description Opossums breed every other areas near water sources. year, having one litter every They have become very The fur of the Virginia two years. Opossums reach common in urban, suburban, opossum is grayish white in the age of sexual maturity at 6 and farming areas. The color and covers the whole to 7 months. opossum is a wanderer and body except the ears and tail. does not stick to a specific They are about the size of a Food Items territory. The opossum uses large house cat, weighing abandoned burrows, tree between 9 and 13 pounds and The opossum is an cavities, hollow logs, attics, having a body length of 24 to insectivore and an omnivore. garages, or building 40 inches. The opossum has a This means they have a foundations. prehensile tail, one which is varied diet of insects, worms, adapted for grasping and fruits, nuts, and carrion (dead hanging. animals). -

Mammals from the Mesozoic of Mongolia

Mammals from the Mesozoic of Mongolia Introduction and Simpson (1926) dcscrihed these as placental (eutherian) insectivores. 'l'he deltathcroids originally Mongolia produces one of the world's most extraordi- included with the insectivores, more recently have narily preserved assemblages of hlesozoic ma~nmals. t)een assigned to the Metatheria (Kielan-Jaworowska Unlike fossils at most Mesozoic sites, Inany of these and Nesov, 1990). For ahout 40 years these were the remains are skulls, and in some cases these are asso- only Mesozoic ~nanimalsknown from Mongolia. ciated with postcranial skeletons. Ry contrast, 'I'he next discoveries in Mongolia were made by the Mesozoic mammals at well-known sites in North Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions America and other continents have produced less (1963-1971) initially led by Naydin Dovchin, then by complete material, usually incomplete jaws with den- Rinchen Barsbold on the Mongolian side, and Zofia titions, or isolated teeth. In addition to the rich Kielan-Jaworowska on the Polish side, Kazi~nierz samples of skulls and skeletons representing Late Koualski led the expedition in 1964. Late Cretaceous Cretaceous mam~nals,certain localities in Mongolia ma~nmalswere collected in three Gohi Desert regions: are also known for less well preserved, but important, Bayan Zag (Djadokhta Formation), Nenlegt and remains of Early Cretaceous mammals. The mammals Khulsan in the Nemegt Valley (Baruungoyot from hoth Early and Late Cretaceous intervals have Formation), and llcrmiin 'ISav, south-\vest of the increased our understanding of diversification and Neniegt Valley, in the Red beds of Hermiin 'rsav, morphologic variation in archaic mammals. which have heen regarded as a stratigraphic ecluivalent Potentially this new information has hearing on the of the Baruungoyot Formation (Gradzinslti r't crl., phylogenetic relationships among major branches of 1977). -

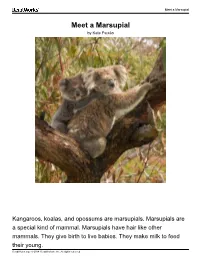

Meet a Marsupial

Meet a Marsupial Meet a Marsupial by Kate Paixão Kangaroos, koalas, and opossums are marsupials. Marsupials are a special kind of mammal. Marsupials have hair like other mammals. They give birth to live babies. They make milk to feed their young. ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Meet a Marsupial But marsupials have something that makes them different from other mammals. Female marsupials have a pouch. They use this pouch to carry their babies. Marsupial babies are called joeys. A joey stays in its mother's pouch for a long time. When it is old enough, the joey gets out and can move around on its own! ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. ReadWorks Vocabulary - mammal mammal mam·mal Definition noun 1. an animal that has hair and feeds its babies with milk from the mother. Dogs, whales, and humans are mammals. Spanish cognate mamífero: The Spanish word mamífero means mammal. These are some examples of how the word or forms of the word are used: 1. Bats are mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that have hair on their bodies. 2. Whales are big ocean mammals. Mammals are animals that drink milk from their mothers. 3. The African elephant is the largest living land mammal, and the ostrich is the largest living bird. 4. The only fish Liza liked were dolphins, except her teacher told her that dolphins were mammals, not fish. 5. Every dog is a mammal. All mammals have hair on their bodies. People, horses, and elephants are also mammals. 6. The Mississippi is home to all kinds of animals. -

Marsupial in Maine: Opossum

Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands www.parksandlands.com Marsupial in Maine: Opossum (Originally published 7/1/2020) If Australia and kangaroos come to mind when you think of marsupials, you are correct. But Maine has one - the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginianus). Marsupials are mammals that do not give birth to fully developed young. The young are instead born when they are extremely tiny and must then crawl to the mother’s pouch. There, they will suckle milk and continue to grow for many weeks. Baby opossums, called pups or pinkies at birth, are no bigger than a honeybee. Curled up on their side, they are no larger round than a dime and weigh in at approximately .13 grams. This is less than a dime, which weighs 2.268 grams (0.080 ounces)! After a week in their mother’s pouch, their birth weight will have increased by ten times. Opossum are skilled tree climbers. Photo by Kim Chandler. After two months, they are mouse-size and will begin exploring briefly outside the pouch. In another month, they will spend more time outside the pouch and may be carried on their mother’s back. They cling tightly to her fur with their hand-like feet and grasping tails. The night-active (nocturnal) opossum is not a fussy eater. It prefers to stay close to its den but may roam up to two miles nightly in search of food. While ambling along trails near a wetland or stream, it will look for insects, worms, frogs, plants, and seeds to eat. Roads, also visited during the nighttime, are sources of dead animals that the opossum will eat. -

A Evolução Dos Metatheria: Sistemática, Paleobiogeografia, Paleoecologia E Implicações Paleoambientais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE TECNOLOGIA E GEOCIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM GEOCIÊNCIAS ESPECIALIZAÇÃO EM GEOLOGIA SEDIMENTAR E AMBIENTAL LEONARDO DE MELO CARNEIRO A EVOLUÇÃO DOS METATHERIA: SISTEMÁTICA, PALEOBIOGEOGRAFIA, PALEOECOLOGIA E IMPLICAÇÕES PALEOAMBIENTAIS RECIFE 2017 LEONARDO DE MELO CARNEIRO A EVOLUÇÃO DOS METATHERIA: SISTEMÁTICA, PALEOBIOGEOGRAFIA, PALEOECOLOGIA E IMPLICAÇÕES PALEOAMBIENTAIS Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado à coordenação do Programa de Pós-graduação em Geociências, da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como parte dos requisitos à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Geociências Orientador: Prof. Dr. Édison Vicente Oliveira RECIFE 2017 Catalogação na fonte Bibliotecária: Rosineide Mesquita Gonçalves Luz / CRB4-1361 (BCTG) C289e Carneiro, Leonardo de Melo. A evolução dos Metatheria: sistemática, paleobiogeografia, paleoecologia e implicações paleoambientais / Leonardo de Melo Carn eiro . – Recife: 2017. 243f., il., figs., gráfs., tabs. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Édison Vicente Oliveira. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. CTG. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, 2017. Inclui Referências. 1. Geociêcias. 2. Metatheria . 3. Paleobiogeografia. 4. Paleoecologia. 5. Sistemática. I. Édison Vicente Oliveira (Orientador). II. Título. 551 CDD (22.ed) UFPE/BCTG-2017/119 LEONARDO DE MELO CARNEIRO A EVOLUÇÃO DOS METATHERIA: SISTEMÁTICA, PALEOBIOGEOGRAFIA, PALEOECOLOGIA E IMPLICAÇÕES PALEOAMBIENTAIS Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado à coordenação do Programa de Pós-graduação -

108 ©2017 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

Technical Session XII (Friday, August 25, 2017, 11:15 AM) We present the first comprehensive exploration of body size evolution in all major amniote clades during the Permo-Triassic (PT). Using phylogenetic comparative methods ELSHAFIE, Sara J., UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States of America that allow for rate variation we examined evolutionary rates in parareptiles, Caudal autotomy, the ability to shed the tail, is common among lizards as a defense archosauromorphs and therapsids. mechanism to escape predation. Caudal autotomy is a basal synapomorphy of Models that allow for rate variation between different branches outperform homogeneous Lepidosauria. About two-thirds of extant lizard families include species that retain the rate models for Parareptilia. Early diverging parareptiles experienced low evolutionary ability. Many can also regenerate the tail after shedding it. The oldest known fossil rates but rates increased to normal with the emergence of the first Ankyramorpha, as evidence of caudal autotomy in a reptile comes from early Permian captorhinids. Here I expected from a Brownian model of evolution. Evolutionary rates accelerated further report the earliest and only documented evidence of caudal autotomy for Squamata, in a with the appearance of the pareiasaurs and peaked within procolophonids at the PT glyptosaurine specimen from the early middle Eocene Bridger Formation in the Bridger boundary. Rates then plateaued in the Triassic, being an order of magnitude higher than Basin of southwestern Wyoming. normal rates. I identified signs of caudal autotomy in this specimen based on disproportions in an intact A heterogeneous rate model is also favoured for Therapsida. Early diverging members of 1.5-cm segment of the tail.