Virginia Opossum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dated Phylogeny of Marsupials Using a Molecular Supermatrix and Multiple Fossil Constraints

Journal of Mammalogy, 89(1):175–189, 2008 A DATED PHYLOGENY OF MARSUPIALS USING A MOLECULAR SUPERMATRIX AND MULTIPLE FOSSIL CONSTRAINTS ROBIN M. D. BECK* School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/89/1/175/1020874 by guest on 25 September 2021 Phylogenetic relationships within marsupials were investigated based on a 20.1-kilobase molecular supermatrix comprising 7 nuclear and 15 mitochondrial genes analyzed using both maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches and 3 different partitioning strategies. The study revealed that base composition bias in the 3rd codon positions of mitochondrial genes misled even the partitioned maximum-likelihood analyses, whereas Bayesian analyses were less affected. After correcting for base composition bias, monophyly of the currently recognized marsupial orders, of Australidelphia, and of a clade comprising Dasyuromorphia, Notoryctes,and Peramelemorphia, were supported strongly by both Bayesian posterior probabilities and maximum-likelihood bootstrap values. Monophyly of the Australasian marsupials, of Notoryctes þ Dasyuromorphia, and of Caenolestes þ Australidelphia were less well supported. Within Diprotodontia, Burramyidae þ Phalangeridae received relatively strong support. Divergence dates calculated using a Bayesian relaxed molecular clock and multiple age constraints suggested at least 3 independent dispersals of marsupials from North to South America during the Late Cretaceous or early Paleocene. Within the Australasian clade, the macropodine radiation, the divergence of phascogaline and dasyurine dasyurids, and the divergence of perameline and peroryctine peramelemorphians all coincided with periods of significant environmental change during the Miocene. An analysis of ‘‘unrepresented basal branch lengths’’ suggests that the fossil record is particularly poor for didelphids and most groups within the Australasian radiation. -

A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes

J Mammal Evol DOI 10.1007/s10914-007-9062-6 ORIGINAL PAPER A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes Robert W. Meredith & Michael Westerman & Judd A. Case & Mark S. Springer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Even though marsupials are taxonomically less diverse than placentals, they exhibit comparable morphological and ecological diversity. However, much of their fossil record is thought to be missing, particularly for the Australasian groups. The more than 330 living species of marsupials are grouped into three American (Didelphimorphia, Microbiotheria, and Paucituberculata) and four Australasian (Dasyuromorphia, Diprotodontia, Notoryctemorphia, and Peramelemorphia) orders. Interordinal relationships have been investigated using a wide range of methods that have often yielded contradictory results. Much of the controversy has focused on the placement of Dromiciops gliroides (Microbiotheria). Studies either support a sister-taxon relationship to a monophyletic Australasian clade or a nested position within the Australasian radiation. Familial relationships within the Diprotodontia have also proved difficult to resolve. Here, we examine higher-level marsupial relationships using a nuclear multigene molecular data set representing all living orders. Protein-coding portions of ApoB, BRCA1, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF were analyzed using maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian methods. Two different Bayesian relaxed molecular clock methods were employed to construct a timescale for marsupial evolution and estimate the unrepresented basal branch length (UBBL). Maximum likelihood and Bayesian results suggest that the root of the marsupial tree is between Didelphimorphia and all other marsupials. All methods provide strong support for the monophyly of Australidelphia. Within Australidelphia, Dromiciops is the sister-taxon to a monophyletic Australasian clade. -

Perissodactyla: Tapirus) Hints at Subtle Variations in Locomotor Ecology

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 277:1469–1485 (2016) A Three-Dimensional Morphometric Analysis of Upper Forelimb Morphology in the Enigmatic Tapir (Perissodactyla: Tapirus) Hints at Subtle Variations in Locomotor Ecology Jamie A. MacLaren1* and Sandra Nauwelaerts1,2 1Department of Biology, Universiteit Antwerpen, Building D, Campus Drie Eiken, Universiteitsplein, Wilrijk, Antwerp 2610, Belgium 2Centre for Research and Conservation, Koninklijke Maatschappij Voor Dierkunde (KMDA), Koningin Astridplein 26, Antwerp 2018, Belgium ABSTRACT Forelimb morphology is an indicator for order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates). Modern terrestrial locomotor ecology. The limb morphology of the tapirs are widely accepted to belong to a single enigmatic tapir (Perissodactyla: Tapirus) has often been genus (Tapirus), containing four extant species compared to that of basal perissodactyls, despite the lack (Hulbert, 1973; Ruiz-Garcıa et al., 1985) and sev- of quantitative studies comparing forelimb variation in eral regional subspecies (Padilla and Dowler, 1965; modern tapirs. Here, we present a quantitative assess- ment of tapir upper forelimb osteology using three- Wilson and Reeder, 2005): the Baird’s tapir (T. dimensional geometric morphometrics to test whether bairdii), lowland tapir (T. terrestris), mountain the four modern tapir species are monomorphic in their tapir (T. pinchaque), and the Malayan tapir (T. forelimb skeleton. The shape of the upper forelimb bones indicus). Extant tapirs primarily inhabit tropical across four species (T. indicus; T. bairdii; T. terrestris; T. rainforest, with some populations also occupying pinchaque) was investigated. Bones were laser scanned wet grassland and chaparral biomes (Padilla and to capture surface morphology and 3D landmark analysis Dowler, 1965; Padilla et al., 1996). was used to quantify shape. -

A Species-Level Phylogenetic Supertree of Marsupials

J. Zool., Lond. (2004) 264, 11–31 C 2004 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904005539 A species-level phylogenetic supertree of marsupials Marcel Cardillo1,2*, Olaf R. P. Bininda-Emonds3, Elizabeth Boakes1,2 and Andy Purvis1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park, Ascot SL5 7PY, U.K. 2 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, U.K. 3 Lehrstuhl fur¨ Tierzucht, Technical University of Munich, Alte Akademie 12, 85354 Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany (Accepted 26 January 2004) Abstract Comparative studies require information on phylogenetic relationships, but complete species-level phylogenetic trees of large clades are difficult to produce. One solution is to combine algorithmically many small trees into a single, larger supertree. Here we present a virtually complete, species-level phylogeny of the marsupials (Mammalia: Metatheria), built by combining 158 phylogenetic estimates published since 1980, using matrix representation with parsimony. The supertree is well resolved overall (73.7%), although resolution varies across the tree, indicating variation both in the amount of phylogenetic information available for different taxa, and the degree of conflict among phylogenetic estimates. In particular, the supertree shows poor resolution within the American marsupial taxa, reflecting a relative lack of systematic effort compared to the Australasian taxa. There are also important differences in supertrees based on source phylogenies published before 1995 and those published more recently. The supertree can be viewed as a meta-analysis of marsupial phylogenetic studies, and should be useful as a framework for phylogenetically explicit comparative studies of marsupial evolution and ecology. -

Monodelphis Domestica in the Opossum Λ Conservation Of

Marsupial Light Chains: Complexity and Conservation of λ in the Opossum Monodelphis domestica This information is current as Julie E. Lucero, George H. Rosenberg and Robert D. Miller of September 29, 2021. J Immunol 1998; 161:6724-6732; ; http://www.jimmunol.org/content/161/12/6724 Downloaded from References This article cites 35 articles, 10 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/161/12/6724.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. http://www.jimmunol.org/ • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average by guest on September 29, 2021 Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 1998 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Marsupial Light Chains: Complexity and Conservation of l in the Opossum Monodelphis domestica1,2 Julie E. Lucero, George H. Rosenberg, and Robert D. Miller3 The Igl chains in the South American opossum, Monodelphis domestica, were analyzed at the expressed cDNA and genomic organization level, the first described for a nonplacental mammal. -

OPOSSUM Didelphis Virginiana

OPOSSUM Didelphis virginiana The Virginia opossum, Didelphis virginiana, is the only marsupial (pouched animal) native to North America. The opossum is not a native species to Vermont, but a population has become established here. The opossum is mostly active at night, being what is referred to as ‘nocturnal.’ They are very good climbers and capable swimmers. These two skills help the opossum avoid predators. It is well known for faking death (also called ‘playing possum’) as another means of outwitting its enemies. The opossum adapts to a wide variety of habitats which has led to its widespread distribution throughout the United States. Vermont Wildlife Fact Sheet Physical Description Opossums breed every other areas near water sources. year, having one litter every They have become very The fur of the Virginia two years. Opossums reach common in urban, suburban, opossum is grayish white in the age of sexual maturity at 6 and farming areas. The color and covers the whole to 7 months. opossum is a wanderer and body except the ears and tail. does not stick to a specific They are about the size of a Food Items territory. The opossum uses large house cat, weighing abandoned burrows, tree between 9 and 13 pounds and The opossum is an cavities, hollow logs, attics, having a body length of 24 to insectivore and an omnivore. garages, or building 40 inches. The opossum has a This means they have a foundations. prehensile tail, one which is varied diet of insects, worms, adapted for grasping and fruits, nuts, and carrion (dead hanging. animals). -

Dominance Relationships in Captive Male Bare-Tailed Woolly Opossum (Caluromys Phiiander, Marsupialia: Didelphidae)

DOMINANCE RELATIONSHIPS IN CAPTIVE MALE BARE-TAILED WOOLLY OPOSSUM (CALUROMYS PHIIANDER, MARSUPIALIA: DIDELPHIDAE) M.-L. GUILLEMIN*, M. ATRAMENTOWICZ* & P. CHARLES-DOMINIQUE* RÉSUMÉ Au cours de ce travail nous avons voulu tester en captivité l'importance du poids corporel dans l'établissement de relations de dominance chez les mâles Caluromysphilander, chez qui des compétitions inter-mâles ont été étudiées. Les comportements et l'évolution de différents paramètres physiologiques ont été observés durant 18 expérimentations effectuées respectivement sur 6 groupes de deux mâles et sur 12 groupes de deux mâles et une femelle. Des relations de dominance-subordination se mettent en place même en l'absence de femelle, mais la compétition est plus forte dans les groupes comprenant une femelle. Dans ces conditions expérimentales, le rang social est basé principalement sur le poids et l'âge. Lorsque la relation de dominance est mise en place, le rang social des mâles est bien défini et il reste stable jusqu'à la fin de l'expérimentation. Ces relations de dominance stables pourraient profiter aux dominants et aux dominés en minimisant les risques de blessures sérieuses. Les mâles montrent des signes typiques caractérisant un stress social : une baisse du poids et de l'hématocrite, les dominés étant plus stressés que les dominants. Chez les mâles dominants, la baisse de l'hématocrite est plus faible que chez les dominés, et la concentration de testostérone dans le sang diminue plus que chez les dominés. Au niveau comportemental, les dominants effectuent la plupart des interactions agonistiques << offensives » et plus d'investigations olfactives de leur environnement (flairage-léchage) que les dominés. -

Moose Foraging in the Temperate Forests of Southern New England Author(S) :Edward K

Moose Foraging in the Temperate Forests of Southern New England Author(s) :Edward K. Faison, Glenn Motzkin, David R. Foster and John E. McDonald Source: Northeastern Naturalist, 17(1):1-18. 2010. Published By: Humboldt Field Research Institute DOI: 10.1656/045.017.0101 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1656/045.017.0101 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non- commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 2010 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 17(1):1–18 Moose Foraging in the Temperate Forests of Southern New England Edward K. Faison1,2,*, Glenn Motzkin1, David R. Foster1, and John E. McDonald3 Abstract - Moose have recently re-colonized the temperate forests of southern New England, raising questions about this herbivore’s effect on forest dynamics in the region. We quantifi ed Moose foraging selectivity and intensity on tree species in rela- tion to habitat features in central Massachusetts. -

Mammals of the Finger Lakes ID Guide

A Guide for FL WATCH Camera Trappers John Van Niel, Co-PI CCURI and FLCC Professor Nadia Harvieux, Muller Field Station K-12 Outreach Sasha Ewing, FLCC Conservation Department Technician Past and present students at FLCC Virginia Opossum Eastern Coyote Eastern Cottontail Domestic Dog Beaver Red Fox Muskrat Grey Fox Woodchuck Bobcat Eastern Gray Squirrel Feral Cat Red Squirrel American Black Bear Eastern Chipmunk Northern Raccoon Southern Flying Squirrel Striped Skunk Peromyscus sp. North American River Otter North American Porcupine Fisher Brown Rat American Mink Weasel sp. White-tailed Deer eMammal uses the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for common and scientific names (with the exception of Domestic Dog) Often the “official” common name of a species is longer than we are used to such as “American Black Bear” or “Northern Raccoon” Please note that it is Grey Fox with an “e” but Eastern Gray Squirrel with an “a”. Face white, body whitish to dark gray. Typically nocturnal. Found in most habitats. About Domestic Cat size. Can climb. Ears and tail tip can show frostbite damage. Very common. Found in variety of habitats. Images are often blurred due to speed. White tail can overexpose in flash. Snowshoe Hare (not shown) is possible in higher elevations. Large, block-faced rodent. Common in aquatic habitats. Note hind feet – large and webbed. Flat tail. When swimming, can be confused with other semi-aquatic mammals. Dark, naked tail. Body brown to blackish (darker when wet). Football-sized rodent. Common in wet habitats. Usually doesn’t stray from water. Pointier face than Beaver. -

Mammals of the Rincon Mountain District, Saguaro National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Mammals of the Rincon Mountain District, Saguaro National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2011/437 ON THE COVER Jaguar killed in Rincon Mountains in 1902, photographed at saloon in downtown Tucson. Photograph courtesy Arizona Historical Society. Mammals of the Rincon Mountain District, Saguaro National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2011/437 Author Don E. Swann With contributions by Melanie Bucci, Matthew Caron, Matthew Daniels, Ronnie Sidner, Sandy A. Wolf, and Erin R. Zylstra Saguaro National Park 3693 South Old Spanish Trail Tucson, Arizona 85730-5601 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd., Suite 303 Tucson, AZ 85710 August 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service’s Natural Resource Stewardship and Science offi ce, in Fort Collins, Colo- rado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the informa- tion is scientifi cally credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Mammals from the Mesozoic of Mongolia

Mammals from the Mesozoic of Mongolia Introduction and Simpson (1926) dcscrihed these as placental (eutherian) insectivores. 'l'he deltathcroids originally Mongolia produces one of the world's most extraordi- included with the insectivores, more recently have narily preserved assemblages of hlesozoic ma~nmals. t)een assigned to the Metatheria (Kielan-Jaworowska Unlike fossils at most Mesozoic sites, Inany of these and Nesov, 1990). For ahout 40 years these were the remains are skulls, and in some cases these are asso- only Mesozoic ~nanimalsknown from Mongolia. ciated with postcranial skeletons. Ry contrast, 'I'he next discoveries in Mongolia were made by the Mesozoic mammals at well-known sites in North Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions America and other continents have produced less (1963-1971) initially led by Naydin Dovchin, then by complete material, usually incomplete jaws with den- Rinchen Barsbold on the Mongolian side, and Zofia titions, or isolated teeth. In addition to the rich Kielan-Jaworowska on the Polish side, Kazi~nierz samples of skulls and skeletons representing Late Koualski led the expedition in 1964. Late Cretaceous Cretaceous mam~nals,certain localities in Mongolia ma~nmalswere collected in three Gohi Desert regions: are also known for less well preserved, but important, Bayan Zag (Djadokhta Formation), Nenlegt and remains of Early Cretaceous mammals. The mammals Khulsan in the Nemegt Valley (Baruungoyot from hoth Early and Late Cretaceous intervals have Formation), and llcrmiin 'ISav, south-\vest of the increased our understanding of diversification and Neniegt Valley, in the Red beds of Hermiin 'rsav, morphologic variation in archaic mammals. which have heen regarded as a stratigraphic ecluivalent Potentially this new information has hearing on the of the Baruungoyot Formation (Gradzinslti r't crl., phylogenetic relationships among major branches of 1977). -

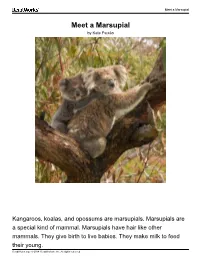

Meet a Marsupial

Meet a Marsupial Meet a Marsupial by Kate Paixão Kangaroos, koalas, and opossums are marsupials. Marsupials are a special kind of mammal. Marsupials have hair like other mammals. They give birth to live babies. They make milk to feed their young. ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Meet a Marsupial But marsupials have something that makes them different from other mammals. Female marsupials have a pouch. They use this pouch to carry their babies. Marsupial babies are called joeys. A joey stays in its mother's pouch for a long time. When it is old enough, the joey gets out and can move around on its own! ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. ReadWorks Vocabulary - mammal mammal mam·mal Definition noun 1. an animal that has hair and feeds its babies with milk from the mother. Dogs, whales, and humans are mammals. Spanish cognate mamífero: The Spanish word mamífero means mammal. These are some examples of how the word or forms of the word are used: 1. Bats are mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that have hair on their bodies. 2. Whales are big ocean mammals. Mammals are animals that drink milk from their mothers. 3. The African elephant is the largest living land mammal, and the ostrich is the largest living bird. 4. The only fish Liza liked were dolphins, except her teacher told her that dolphins were mammals, not fish. 5. Every dog is a mammal. All mammals have hair on their bodies. People, horses, and elephants are also mammals. 6. The Mississippi is home to all kinds of animals.