Ancient Egyptian Coffins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Home Cemetery (41FB334)

Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State Volume 2012 Article 1 2012 New Home Cemetery (41FB334): Archaeological Search Exhumation, and Reinterment of Multiple Historic Graves along FM 1464, Sugar Land, Fort Bend County, Texas Mary Cassandra Hill Jeremy W. Pye Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Cultural Resource Management and Policy Analysis Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History Commons, Human Geography Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Hill, Mary Cassandra and Pye, Jeremy W. (2012) "New Home Cemetery (41FB334): Archaeological Search Exhumation, and Reinterment of Multiple Historic Graves along FM 1464, Sugar Land, Fort Bend County, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2012 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.2012.1.1 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2012/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Home Cemetery (41FB334): Archaeological Search Exhumation, and Reinterment of Multiple Historic Graves along FM 1464, Sugar Land, Fort Bend County, Texas Licensing Statement This is a work for hire produced for the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), which owns all rights, title, and interest in and to all data and other information developed for this project under its contract with the report producer. -

A Preliminary Study of the Inner Coffin and Mummy Cover Of

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF THE INNER COFFIN AND MUMMY COVER OF NESYTANEBETTAWY FROM BAB EL-GUSUS (A.9) IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, WASHINGTON, D.C. by Alec J. Noah A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History The University of Memphis May 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alec Noah All rights reserved ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I must thank the National Museum of Natural History, particularly the assistant collection managers, David Hunt and David Rosenthal. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Nigel Strudwick, for his guidance, suggestions, and willingness to help at every step of this project, and my thesis committee, Dr. Lorelei H. Corcoran and Dr. Patricia V. Podzorski, for their detailed comments which improved the final draft of this thesis. I would like to thank Grace Lahneman for introducing me to the coffin of Nesytanebettawy and for her support throughout this entire process. I am also grateful for the Lahneman family for graciously hosting me in Maryland on multiple occasions while I examined the coffin. Most importantly, I would like to thank my parents. Without their support, none of this would have been possible. iv ABSTRACT Noah, Alec. M.A. The University of Memphis. May 2013. A Preliminary Study of the Inner Coffin and Mummy Cover of Nesytanebettawy from Bab el-Gusus (A.9) in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Major Professor: Nigel Strudwick, Ph.D. The coffin of Nesytanebettawy (A.9) was retrieved from the second Deir el Bahari cache in the Bab el-Gusus tomb and was presented to the National Museum of Natural History in 1893. -

The Stirrup Court Cemetery Coffin Hardware

WOODLEY: STIRRUP COURT CEMETERY 45 The Stirrup Court Cemetery Coffin Hardware Philip J. Woodley This report presents the analysis of the coffin unknown before human remains were uncovered in hardware from the 19th century Euro-Canadian the course of house construction. Most of the Stirrup Court Cemetery. The results of this analysis burials were excavated in situ (Fig. 2) but skeletal and comparisons with other cemeteries has produced material and one coffin plaque were recovered from a chronology of coffin shape and coffin hardware for fill piles in other parts of London (Cook, Gibbs and 19th century southern Ontario. Both rectangular Spence 1986: 107). It is believed "...that most of the coffins and coffin hardware had been introduced by burials in the cemetery were removed, and that most mid-century, and hardware was increasingly used (though certainly not all) of the human bone from and varied by the late 1800s. the disturbed area and the fill locations was The results of this chronology are combined with recovered" (Cook, Gibbs and Spence 1986: 107). historical and skeletal data to determine the identity of Where hardware is assigned to a particular grave in the individuals buried at Stirrup Court. Relative cost this article, it was recovered by the excavations; the can be estimated for coffins, but there is no simple coffin plaque with no grave assignment was correlation between social status and the quantity of recovered from the fill pile. coffin hardware. There were approximately twenty-seven in- dividuals originally buried in the cemetery of which six had previously been exhumed (Cook, Gibbs and Introduction: Spence 1986). -

Catholic Covid-19 Handling

ICRC REGIONAL DELEGATION TO INDONESIA AND TIMOR-LESTE GUIDELINES ON MANAGEMENT OF THE DEAD WITH COVID-19 FOR PROTESTANTS TO CHRISTIAN MINISTERS, CONGREGATION, AND CHRISTIAN BELIEVERS, The Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to Indonesia and Timor-Leste in Jakarta has provided support to the Government of Indonesia along with both governmental and non-governmental agencies in efforts to manage COVID-19. On this occasion, the ICRC wants to extend its gratitude and appreciation to religious leaders, traditional leaders and community leaders who have actively participated in delivering important messages related to COVID-19, including management of the dead, whether in positive confirmed cases, people under monitoring, and patients under supervision. To clarify some of the key messages that have been circulated, below is the summary of information related to management of the dead for victims of COVID-19 compiled by the ICRC based on references from authorities, international agencies, the the Association of Churches of Indonesia (PGI) and recommendations from the ICRC’s forensics experts. This message needs to be disseminated in order to uphold human dignity, both for the living and for the dead. MANAGEMENT OF THE DEAD • In funeral rites during the COVID-19 pandemic all dead bodies must be treated as COVID-19 positive and considered to be contagious. Therefore the handling of the body should follow government regulations and medical protocol. • The body should only be treated by trained health personnel or those who are authorized to use standard personal protective equipment. • All components of the protective suits should be kept in a place separated from ordinary clothes. -

Cremation-2016.Pdf

Cremation Cremation is the act of reducing a corpse to ashes by burning, generally in a crematorium furnace or crematory fire. In funerals, cremation can be an alternative funeral rite to the burial of a body in a grave. Modern Cremation Process The cremation occurs in a 'crematorium' which consists of one or more cremator furnaces or cremation 'retorts' for the ashes. A cremator is an industrial furnace capable of generating 870-980 °C (1600-1800 °F) to ensure disintegration of the corpse. A crematorium may be part of chapel or a funeral home, or part of an independent facility or a service offered by a cemetery. Modern cremator fuels include natural gas and propane. However, coal or coke was used until the early 1960s. Modern cremators have adjustable control systems that monitor the furnace during cremation. A cremation furnace is not designed to cremate more than one body at a time, which is illegal in many countries including the USA. The chamber where the body is placed is called the retort. It is lined with refractory brick that retain heat. The bricks are typically replaced every five years due to heat stress. © 2016 All Star Training, Inc. Page 1 Modern cremators are computer-controlled to ensure legal and safe use, e.g. the door cannot be opened until the cremator has reached operating temperature. The coffin is inserted (charged) into the retort as quickly as possible to avoid heat loss through the top- opening door. The coffin may be on a charger (motorized trolley) that can quickly insert the coffin, or one that can tilt and tip the coffin into the cremator. -

FUNERALS WITHOUT a FUNERAL DIRECTOR Information It Is Often

FUNERALS WITHOUT A FUNERAL DIRECTOR Information It is often assumed, quite wrongly, that funerals can be completed only with the use of a funeral director. Although a funeral director will be invited to organise the majority of funerals, some people prefer to organise funerals themselves. The details in the individual sections of this Charter give sufficient information to achieve this. Your Charter member will also supply a leaflet giving you local information. The funeral director typically organises the funeral by collecting and moving the body, arranging embalming and viewing of the deceased, providing a coffin, hearse and other elements. Carrying out these services relieves the bereaved from doing what they may feel are unpleasant and difficult tasks. Ultimately, the funeral director must operate commercially and in charging for his or her services, funerals can be expensive. In addition, the funeral director imposes him/herself on the arrangements to a greater or lesser degree. Some people do not wish to use a funeral director. This can be for a wide variety of reasons. They may feel that passing the body of a loved one over to strangers is wrong. Some feel that personally organising the funeral is their final tribute to the deceased person. Others may simply wish to save money by doing everything themselves or may have used a funeral director on a previous occasion and found the experience unsatisfactory. Some may feel that funerals arranged with a funeral director are routine and processed, and may desire an innovative and different approach. It is, of course, your right to make this decision without giving a reason. -

Title 310 - Oklahoma State Department of Health

Title 310 - Oklahoma State Department of Health Chapter 105 - Vital Statistics Subchapter 7 - Bodies and Relocation of Cemeteries 310:105-7-1. Transportation of bodies (a) Bodies shipped by common carrier. The body of any person dead of a disease that is not contagious, infectious, or communicable may be shipped by common carrier subject to the following conditions: (1) Provided the body is encased in a sound coffin or casket, enclosed in a strong outside shipping case, and provided it can reach destination within the specified number of hours from the time of death, applicable both to place of shipment and destination. (2) When shipment cannot reach destination within the number of hours specified, the body shall either (A) Be embalmed, encased in a sound coffin or casket, and enclosed in a strong outside case for shipment, or (B) When embalming is not possible, or if the body is in a state of decomposition, it shall be shipped only after enclosure in an airtight coffin or casket, enclosed in proper shipping container. (3) A burial transit permit shall be attached in a strong envelope to the shipping case. (b) Transportation of certain diseased bodies. The body of any person dead of smallpox, Asiatic cholera, louse-borne typhus fever, plague, yellow fever or any other contagious, infectious or communicable disease shall not be transported unless: (1) Such body has been embalmed, properly disinfected and encased in an airtight zinc, tin, copper, or lead-lined coffin or iron casket, all joints and seams hermetically soldered or sealed and all encased in a strong, tight outside shipping case. -

Module 3 Funeral Directing Operations

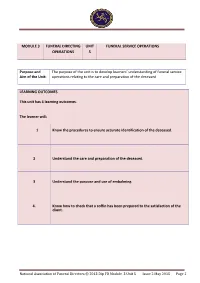

MODULE 3 FUNERAL DIRECTING UNIT FUNERAL SERVICE OPERATIONS OPERATIONS 5 Purpose and The purpose of the unit is to develop learners’ understanding of funeral service Aim of the Unit: operations relating to the care and preparation of the deceased. LEARNING OUTCOMES This unit has 4 learning outcomes. The learner will: 1 Know the procedures to ensure accurate identification of the deceased. 2 Understand the care and preparation of the deceased. 3 Understand the purpose and use of embalming. 4. Know how to check that a coffin has been prepared to the satisfaction of the client. National Association of Funeral Directors © 2013 Dip FD Module 3 Unit 5 Issue 2 May 2015 Page 1 Introduction It is the Funeral Director’s duty to care for the deceased from the time the body comes under his/ her control until the time of committal. This means that whether the deceased is in hospital, a nursing home or the Coroner’s / Procurator Fiscal mortuary, once the body is released to the Funeral Director it is his/her duty to care for that person until the time of committal, whenever that may be. Learning Outcome 1 Know the procedures to ensure accurate identification of the deceased. It is absolutely essential that accurate identification checks are made at every stage of bringing the Deceased into your care to make sure that the Deceased is the correct person. National Association of Funeral Directors © 2013 Dip FD Module 3 Unit 5 Issue 2 May 2015 Page 2 IDENTIFICATION PROCEDURES - ADMINISTRATION NAFD Guidelines There is nothing more important to the families of the deceased than their loved one being correctly identified at all times while in the care of the funeral home. -

7 Tradition-Based Concepts of Death, Burial and Afterlife: a Case from Orthodox Setomaa, South-Eastern Estonia

Heiki Valk 7 Tradition-based Concepts of Death, Burial and Afterlife: A Case from Orthodox Setomaa, South-Eastern Estonia Introduction Interpreting the archaeological record is an eternal question for archaeology. One way to escape it is to remain limited by presenting data in a descriptive manner, but such an approach does not pave the way for deeper comprehension. To understand the record, different tools should be used for interpretations. Concerning burial archaeology of post-medieval times, ethnological and folkloric data can be of great value, especially if originating from a geographically and culturally close tradition-based context. If customs recorded in burial archaeology correspond to those known from folkloric or ethnological context, oral data can provide an extra dimension for understanding the former concepts of death and afterlife, also in reference to the spheres that are not reflected in the archaeological record at all, thus putting some flesh on the bones of burial archaeology. The cultural convergence of Europe has unified the concepts of death and afterlife in two powerful waves. First, in the context of Christianization, and second in the frameworks of modernization and secularization, especially since the 20th century. As the result, earlier concepts of death and burial, those emerging with their roots from pre-Christian times, have disappeared or have been pushed to the fringes of memory. However, peripheral areas where cultural processes have been slower and old traditions had a longer persistence, sometimes enable the researchers to look into the past with death concepts totally different from both those of modern times, as well as of those of Christian character. -

Tulsa Race Massacre Investigation Oaklawn Cemetery Executive Summary of 2020 Test Excavations

Tulsa Race Massacre Investigation Oaklawn Cemetery Executive Summary of 2020 Test Excavations Presented by the Physical Investigation Committee By Kary Stackelbeck, Ph.D. and Phoebe Stubblefield, Ph.D. with contributions by: Debra Green, Ph.D., Leland Bement, Ph.D., Amanda Regnier, Ph.D., Scott Hammerstedt, Ph.D., Angela Berg, M.A., and Scott Ellsworth, Ph.D. Key Findings: • Test excavations in the Sexton Area (July 13-22, 2020): o No evidence of a mass grave or any other human remains was identified. o Excavations revealed evidence of two historic roads and several episodes of dumping of debris, early to mid-20th century artifacts, and soil from other locations that collectively resulted in the accumulation of about 10 feet of fill over the sloped surface that we believe would have been present in the early 1900’s. o Excavations also revealed a low-lying swampy area near the southern end of the Sexton Area that contains very dark, wet soil, numerous artifacts, fragments of wood, and some non-human bone. • Soil Cores and Augers excavated in the Clyde Eddy Area (October 19-22, 2020): o No evidence of a mass grave or any other human remains was identified in the soil core samples. o From these results, it is possible that we are not looking in the same location indicated by Mr. Eddy or where the earlier geophysical survey (Brooks and Witten 2001) identified a promising anomaly. o Further investigation is needed. • Test excavations in the Original 18 Area (October 19-22, 2020): o Test excavations revealed a mass grave that contains the remains of at least 12 individuals based largely on evidence for coffins and coffin hardware. -

Guidance Information on the Transport of COVID-19 Human Remains By

Guidance Information on the Transport of COVID-19 Human Remains by Air Collaborative document by WHO, CDC, IATA and ICAO Introduction Repatriation of human remains is the process whereby human remains are transported from the State where death occurred to another State for burial at the request of the next-of-kin. Repatriating human remains is a complicated process involving the cooperation and coordination of various stakeholders on several levels to ensure that it is conducted efficiently and in compliance with relevant international and national regulations. Presently there is no universal international standard for requisite processing and documentation for repatriation of human remains by air. The Strasbourg Agreement of the Council of Europe (https://rm.coe.int/168007617d) has been agreed to by more than 20 States in Europe. Furthermore, there is no existing single source document that could provide harmonised guidance to States and other interested parties. Considering requests received by WHO, IATA and ICAO on the transport by air of human remains where the cause of death was COVID-19, there was a need to assess the risk of transporting human remains by air and to develop temporary COVID-19 specific guidance material. The objective of this document is to provide guidance to aircraft operators, funeral directors and other involved parties concerning the factors that need to be considered when planning repatriation of COVID-19 human remains by air transport. Guidance for handling COVID-19 cadavers The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a considerable death toll and has raised questions regarding the repatriation of human remains where the person died of the disease overseas. -

Can a Cremation Be Arranged Without the Services of a Funeral Director?

Questions Frequently Asked Regarding Cremation Can a cremation be arranged without the services of a funeral director? Yes. The Executor or nearest surviving relative may arrange the cremation service themselves. The Bereavement Services Team will provide advice to persons arranging a cremation without the use of a funeral director. Can more than one body be cremated at a time? No. The only exception permitted to this rule is in the case of a mother and baby, or twin children, when the next of kin requests that the two are cremated together. Do any religious groups forbid cremation? All Christian denominations, including the Roman Catholic Church, allow cremation, as do Sikhs, Hindus, Parsees and Buddhists. It is however forbidden by Orthodox Jews and Muslims. How is a cremation arranged? The Cremation Regulations are complex and many people approach a funeral director immediately after a death occurs to advise that they wish to arrange a cremation. The funeral director will ensure that all the necessary forms for cremation are obtained and presented to the Crematorium. How soon after the service will the cremation take place? Under normal circumstances the cremation is usually carried out shortly after the service, and usually on the same day. Is the coffin cremated with the body? Yes. The Code of Cremation Practice requires that nothing be removed from the coffin after it has been received from the chapel, and must be placed into the cremator exactly as received. What religious ceremony can I have with a cremation? The service for burial and cremation is the same apart from the form of committal sentences.