Arxiv:1212.6756V1 [Math.CO] 30 Dec 2012 Σ of O Hypergraph a for a O Vr W Ijitedges Disjoint Two Every for a Let Introduction 1 Ento 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Special Planar Satisfiability Problem and a Consequence of Its NP-Completeness

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector DISCRETE APPLIED MATHEMATICS ELSEVIER Discrete Applied Mathematics 52 (1994) 233-252 A special planar satisfiability problem and a consequence of its NP-completeness Jan Kratochvil Charles University, Prague. Czech Republic Received 18 April 1989; revised 13 October 1992 Abstract We introduce a weaker but still NP-complete satisfiability problem to prove NP-complete- ness of recognizing several classes of intersection graphs of geometric objects in the plane, including grid intersection graphs and graphs of boxicity two. 1. Introduction Intersection graphs of different types of geometric objects in the plane gained more attention in recent years, mainly in connection with fast development of computa- tional geometry and computer science. Just to mention the most frequently cited classes, these are interval graphs, circular arc graphs, circle graphs, permutation graphs, etc. If we consider only connected objects (more precisely arc-connected sets) the most general class of intersection graphs are string graphs (intersection graphs of curves in the plane) which were originally introduced by Sinden [16] in the connection with thin film RC-circuits. String graphs were then considered by several authors [4,6,7]. In a recent paper [S], I have shown that recognition of string graphs is NP-hard and in fact, the method developed in [S] is refined in this note to obtain other NP- completeness results. It is striking that so far no finite algorithm for string graph recognition is known. It seems that relatively simpler classes will arise if we consider straight-line segments instead of curves and furthermore, if these segments are allowed to follow only a bounded number of directions. -

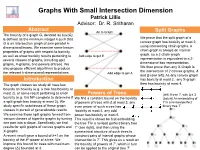

Graphs with Small Intersection Dimension Patrick Lillis Advisor: Dr

Graphs With Small Intersection Dimension Patrick Lillis Advisor: Dr. R. Sritharan Abstract An X-Graph Split Graphs The boxicity of a graph G, denoted as box(G), We prove that the split graph of a is defined as the minimum integer k such that G is an intersection graph of axis-parallel k- convex graph has boxicity at most 2, dimensional boxes. We examine some known using intersecting chain graphs. A properties of graphs with respect to boxicity, chain graph is always an interval graph, so a 2 chain graph as well as show boxicity results pertaining to Add edge to get B several classes of graphs, including split representation is equivalent to a 2- graphs, X-graphs, and powers of trees. We dimensional box representation. also propose efficient algorithms to produce We then prove than any X-Graph is the intersection of 2 convex graphs, A the relevant k-dimensional representations. Add edge to get A and B (see left). As any convex graph Introduction has boxicity at most 2, any X-graph The graph classes we study all have low then has boxicity at most 4. bounds on boxicity (e.g. a tree has boxicity at most 2), or some result pertaining to small Powers of Trees (left) A tree T, with Δ ≤ 3 boxicity (e.g. it is NP-complete to determine if We find a constant bound on the boxicity (below) An embedding of a split graph has boxicity at most 3). We of powers of trees with Δ at most 3; any T in a revised perfect study specific subclasses of these graph even power of such a tree has binary tree T’. -

Geometric Representations of Graphs

' $ Geometric Representations of Graphs L. Sunil Chandran Assistant Professor Comp. Science and Automation Indian Institute of Science Bangalore- 560012. Email: [email protected] & 1 % ' $ • Conventionally graphs are represented as adjacency matrices, or adjacency lists. Algorithms are designed with such representations in mind usually. • It is better to look at the structure of graphs and find some representations that are suitable for designing algorithms- say for a class of problems. • Intersection graphs: The vertices correspond to the subsets of a set U. The vertices are made adjacent if and only if the corresponding subsets intersect. • We propose to use some nice geometric objects as the subsets- like spheres, cubes, boxes etc. Here U will be the set of points in a low dimensional space. & 2 % ' $ • There are many situations where an intersection graph of geometric objects arises naturally.... • Some times otherwise NP-hard algorithmic problems become polytime solvable if we have geometric representation of the graph in a space of low dimension. & 3 % ' $ Boxicity and Cubicity • Cubicity: Minimum dimension k such that G can be represented as the intersection graph of k-dimensional cubes. • Boxicity: Minimum dimension k such that G can be represented as the intersection graph of k-dimensional axis parallel boxes. • These concepts were introduced by F. S. Roberts, in 1969, motivated by some problems in ecology. • By the later part of eighties, the research in this area had diminished. & 4 % ' $ An Equivalent Combinatorial Problem • The boxicity(G) is the same as the minimum number k such that there exist interval graphs I1,I2,...,Ik such that G = I1 ∩ I2 ∩···∩ Ik. -

Box Representations of Embedded Graphs

Box representations of embedded graphs Louis Esperet CNRS, Laboratoire G-SCOP, Grenoble, France S´eminairede G´eom´etrieAlgorithmique et Combinatoire, Paris March 2017 Definition (Roberts 1969) The boxicity of a graph G, denoted by box(G), is the smallest d such that G is the intersection graph of some d-boxes. Ecological/food chain networks Sociological/political networks Fleet maintenance Boxicity d-box: the cartesian product of d intervals [x1; y1] ::: [xd ; yd ] of R × × Ecological/food chain networks Sociological/political networks Fleet maintenance Boxicity d-box: the cartesian product of d intervals [x1; y1] ::: [xd ; yd ] of R × × Definition (Roberts 1969) The boxicity of a graph G, denoted by box(G), is the smallest d such that G is the intersection graph of some d-boxes. Ecological/food chain networks Sociological/political networks Fleet maintenance Boxicity d-box: the cartesian product of d intervals [x1; y1] ::: [xd ; yd ] of R × × Definition (Roberts 1969) The boxicity of a graph G, denoted by box(G), is the smallest d such that G is the intersection graph of some d-boxes. Ecological/food chain networks Sociological/political networks Fleet maintenance Boxicity d-box: the cartesian product of d intervals [x1; y1] ::: [xd ; yd ] of R × × Definition (Roberts 1969) The boxicity of a graph G, denoted by box(G), is the smallest d such that G is the intersection graph of some d-boxes. Ecological/food chain networks Sociological/political networks Fleet maintenance Boxicity d-box: the cartesian product of d intervals [x1; y1] ::: [xd ; yd ] of R × × Definition (Roberts 1969) The boxicity of a graph G, denoted by box(G), is the smallest d such that G is the intersection graph of some d-boxes. -

Combinatorialalgorithms for Packings, Coverings and Tilings Of

Departm en t of Com m u n ication s an d Networkin g Aa lto- A s hi k M a thew Ki zha k k ep a lla thu DD 112 Combinatorial Algorithms / 2015 for Packings, Coverings and Tilings of Hypercubes Combinatorial Algorithms for Packings, Coverings and Tilings of Hypercubes Hypercubes of Tilings and Coverings Packings, for Algorithms Combinatorial Ashik Mathew Kizhakkepallathu 9HSTFMG*agdcgd+ 9HSTFMG*agdcgd+ ISBN 978-952-60-6326-3 (printed) BUSINESS + ISBN 978-952-60-6327-0 (pdf) ECONOMY ISSN-L 1799-4934 ISSN 1799-4934 (printed) ART + ISSN 1799-4942 (pdf) DESIGN + ARCHITECTURE Aalto Un iversity Aalto University School of Electrical Engineering SCIENCE + Department of Communications and Networking TECHNOLOGY www.aalto.fi CROSSOVER DOCTORAL DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS DISSERTATIONS Aalto University publication series DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS 112/2015 Combinatorial Algorithms for Packings, Coverings and Tilings of Hypercubes Ashik Mathew Kizhakkepallathu A doctoral dissertation completed for the degree of Doctor of Science (Technology) to be defended, with the permission of the Aalto University School of Electrical Engineering, at a public examination held at the lecture hall S1 of the school on 18 September 2015 at 12. Aalto University School of Electrical Engineering Department of Communications and Networking Information Theory Supervising professor Prof. Patric R. J. Östergård Preliminary examiners Dr. Mathieu Dutour Sikirić, Ruđer Bošković Institute, Croatia Prof. Aleksander Vesel, University of Maribor, Slovenia Opponent Prof. Sándor Szabó, University of Pécs, Hungary Aalto University publication series DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS 112/2015 © Ashik Mathew Kizhakkepallathu ISBN 978-952-60-6326-3 (printed) ISBN 978-952-60-6327-0 (pdf) ISSN-L 1799-4934 ISSN 1799-4934 (printed) ISSN 1799-4942 (pdf) http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-6327-0 Unigrafia Oy Helsinki 2015 Finland Abstract Aalto University, P.O. -

Boxicity, Poset Dimension, and Excluded Minors

Boxicity, poset dimension, and excluded minors Louis Esperet∗ Veit Wiechert Laboratoire G-SCOP Institut f¨urMathematik CNRS, Univ. Grenoble Alpes Technische Universit¨atBerlin Grenoble, France Berlin, Germany [email protected] Submitted: Apr 12, 2018; Accepted: Nov 27, 2018; Published: Dec 21, 2018 c The authors. Abstract In this short note, we relate the boxicity of graphs (and the dimension of posets) with their generalized coloring parameters. In particular, together with known estimates, our results imply that any graph with no Kt-minor can be represented as the intersection of O(t2 log t) interval graphs (improving the previous bound of 4 15 2 O(t )), and as the intersection of 2 t circular-arc graphs. Mathematics Subject Classifications: 05C15, 05C83, 06A07 1 Introduction The intersection G1 \···\ Gk of k graphs G1;:::;Gk defined on the same vertex set V , is the graph (V; E1 \:::\Ek), where Ei (1 6 i 6 k) denotes the edge set of Gi. The boxicity box(G) of a graph G, introduced by Roberts [19], is defined as the smallest k such that G is the intersection of k interval graphs. Scheinerman proved that outerplanar graphs have boxicity at most two [20] and Thomassen proved that planar graphs have boxicity at most three [24]. Outerplanar graphs have no K4-minor and planar graphs have no K5-minor, so a natural question is how these two results extend to graphs with no Kt-minor for t > 6. It was proved in [6] that if a graph has acyclic chromatic number at most k, then its boxicity is at most k(k − 1). -

Contact Representations of Planar Graphs with Cubes

Contact representations of planar graphs with cubes Stefan Felsner∗ Mathew C. Francis [email protected] [email protected] Technische Universit¨at Berlin Department of Applied Mathematics, Institut f¨ur Mathematik Charles University Strasse des 17. Juni 136 Malostransk´eN´am. 25, 10623 Berlin, Germany 118 00 Praha 1, Czech Republic Abstract. We prove that every planar graph has a representation using axis-parallel cubes in three dimensions in such a way that there is a cube corresponding to each vertex of the planar graph and two cubes have a non-empty intersection if and only if their corresponding vertices are adjacent. Moreover, when two cubes have a non-empty intersection, they just touch each other. This result is a strengthening of a result by Thomassen which states that every planar graph has such a representation using axis-parallel boxes. 1 Introduction An axis-aligned d-dimensional box, or d-box in short, is defined to be the Cartesian product of d closed intervals. The boxicity of a graph G is defined as the smallest d such that G can be represented as the intersection graph of d-boxes in IRd . A graph has boxicity at most one if and only if it is an interval graph. Roberts [12] showed that removing a perfect matching from a complete graph on 2n vertices yields a graph of boxicity n. The octahedron graph is the instance with n = 3 from this series of examples. This shows that the boxicity of planar graphs can be as large as 3. Thomassen [16] proved that the boxicity of planar graphs is at most 3. -

Boxicity and Cubicity of Product Graphs

Boxicity and Cubicity of Product Graphs L. Sunil Chandran1, Wilfried Imrich2, Rogers Mathew ∗3, and Deepak Rajendraprasad †1 1 Department of Computer Science and Automation, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India - 560012. {sunil, deepakr}@csa.iisc.ernet.in 2 Department Mathematics and Information Technology, Montanuniversit¨at Leoben, Austria. [email protected] 3 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada - B3H 3J5. [email protected] Abstract The boxicity (cubicity) of a graph G is the minimum natural number k such that G can be represented as an intersection graph of axis-parallel rectangular boxes (axis-parallel unit cubes) in Rk. In this article, we give estimates on the boxic- ity and the cubicity of Cartesian, strong and direct products of graphs in terms of invariants of the component graphs. In particular, we study the growth, as a function of d, of the boxicity and the cubicity of the d-th power of a graph with respect to the three products. Among others, we show a surprising result that the boxicity and the cubicity of the d-th Cartesian power of any given finite graph is in O(logd/loglogd) and Θ(d/log d), respectively. On the other hand, we show that there cannot exist any sublinear bound on the growth of the boxicity of powers of a general graph with respect to strong and direct products. Keywords: intersection graphs, boxicity, cubicity, graph products, boolean lattice. 1 Introduction Throughout this discussion, a k-box is the Cartesian product of k closed intervals on the real line R, and a k-cube is the Cartesian product of k closed unit length intervals k arXiv:1305.5233v1 [math.CO] 22 May 2013 on R. -

Boxicity, Cubicity and Vertex Cover

Boxicity, Cubicity and Vertex Cover A Thesis Submitted For the Degree of Master of Science (Engineering) in the Faculty of Engineering by Chintan D. Shah Computer Science and Automation Indian Institute of Science BANGALORE – 560 012 August 2008 Acknowledgements I want to thank my research advisor Dr. L. Sunil Chandran for his guidance, perseverance and for the faith he has shown in me. It was in no way possible for me to write this thesis without his encouragement and support. All the work for this thesis was done under his guidance. It is an honour to mention that my parents and my brother made it possible, in every sense of the word, for me to be what I am today. Megha has also been very supportive. I would also like to thank Dr. Anita Das for her encouragement, for all the discussions we had and for bearing with all my thoughts throughout all the work done for this thesis. Manu helped in proofreading the thesis. I would like to thank the faculty and staff of CSA department for all the support and especially Dr. Dilip P. Patil, Dr. Sathish Govindarajan, Dr. T. Kavitha, Dr. Ramesh Hariharan and the Chairman (Dr. M. Narasimha Murty) for sharing their knowledge with me and for advising me. I would also like to thank all my friends, especially Nayan, Subramanya, Rashmin, Rajdeep, Amrish, Arvind, Naveen, Vinoj, Tushar, Rajan(Deepak), Manu, Jayakumar, Raveendra, Hitesh, Arun Rangasamy, Arun Chandra, Ved Prakash Arya, Sanjay, Mayur, Vishal, Urvang, Keyur, Prachee, Tarun, Ramasya(Deepak), Rogers, Mathew Francis, Meghana, Abhijin, Tejas, Prashanth, Ranganath, Ramanjit, Dinesh, Shobhit and Sub- hajit for making my stay at IISc memorable and for all the fun we had together. -

On the Boxicity and Cubicity of Hypercubes

On the boxicity and cubicity of hypercubes L. Sunil Chandran ⋆ and Naveen Sivadasan ⋆⋆ Abstract. For a graph G, its cubicity cub(G) is the minimum dimension k such that G is representable as the intersection graph of (axis–parallel) cubes in k–dimensional space. Chandran et al. [2] showed that for a d– d−1 Hd Hd d dimensional hypercube , log d ≤ cub( ) ≤ 2 . In this paper, we show d Hd Θ that cub( ) = log d . The parameter boxicity generalizes cubicity: the boxicity box(G) of a graph G is defined as the minimum dimension k such that G is representable as the intersection graph of axis parallel boxes in k dimensional space. Since box(G) ≤ cub(G) for any graph G, d Hd O our result implies that box( )= log d . The problem of determining a non-trivial lower bound for box(Hd) is left open. 1 Introduction Let = S U : x V be a family of subsets of a universe U, F { x ⊆ ∈ } where V is an index set. The intersection graph Ω( ) of has V as F F vertex set, and two distinct vertices x and y are adjacent if and only if S S = . Representations of graphs as the intersection graphs of x ∩ y 6 ∅ various geometrical objects is a well studied topic in graph theory. Two well-known concepts in this area of graph theory are the cubicity and the boxicity. These concepts were introduced by F. S. Roberts in 1969 [12] and they find applications in niche overlap in ecology and to problems of fleet maintenance in operations research. -

Complexity Results on Graphs with Few Cliques Bill Rosgen, Lorna Stewart

Complexity results on graphs with few cliques Bill Rosgen, Lorna Stewart To cite this version: Bill Rosgen, Lorna Stewart. Complexity results on graphs with few cliques. Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science, DMTCS, 2007, 9 (1), pp.127–135. hal-00966509 HAL Id: hal-00966509 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00966509 Submitted on 26 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science DMTCS vol. 9, 2007, 127–136 Complexity Results on Graphs with Few Cliques Bill Rosgen1 and Lorna Stewart2 1 Institute for Quantum Computing and School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2 Department of Computing Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada received Oct 21, 2005, revised June 25, 2007, accepted July 4, 2007. A graph class has few cliques if there is a polynomial bound on the number of maximal cliques contained in any member of the class. This restriction is equivalent to the requirement that any graph in the class has a polynomial sized intersection representation that satisfies the Helly property. On any such class of graphs some problems that are NP-complete on general graphs, such as the maximum clique problem and the maximum weighted clique problem, admit polynomial time algorithms. -

Structural Parameterizations for Boxicity

Structural parameterizations for boxicity Henning Bruhn, Morgan Chopin, Felix Joos and Oliver Schaudt Abstract The boxicity of a graph G is the least integer d such that G has an intersection model of axis-aligned d-dimensional boxes. Boxicity, the problem of deciding whether a given graph G has boxicity at most d, is NP-complete for every fixed d ≥ 2. We show that Boxicity is fixed- parameter tractable when parameterized by the cluster vertex deletion number of the input graph. This generalizes the result of Adiga et al., that Boxicity is fixed-parameter tractable in the vertex cover number. Moreover, we show that Boxicity admits an additive 1-approximation when parameterized by the pathwidth of the input graph. Finally, we provide evidence in favor of a conjecture of Adiga et al. that Boxicity remains NP-complete when parameterized by the treewidth. 1 Introduction Every graph G can be represented as an intersection graph of axis-aligned boxes in Rd, provided d is large enough. The boxicity of G, introduced by Roberts [18], is the smallest dimension d for which this is possible. We denote the correspond- ing decision problem by Boxicity: given G and d 2 N, determine whether G has boxicity at most d. Boxicity has received a fair amount of attention. This is partially due to the wider context of graph representations, but also because graphs of low boxicity are interesting from an algorithmic point of view. While many hard problems remain so for graphs of bounded boxicity, some become solvable in polynomial time, notably max-weighted clique (as observed by Spinrad [20, p.