Dylan Gottlieb on Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENIDO Por AUTOR

ÍNDICE de CONTENIDO por AUTOR Arquitectos de México Autor Artículo No Pg A Abud, Antonio Casa habitación 04/5 44 Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y una breve descripción. Abud, Antonio Casa habitación (2) 04/05 48 Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y una breve descripción. Abud, Antonio Edificio de apartamentos 04/05 52 Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y una breve descripción. Abud Nacif, Edificio de productos en la 11 56 Antonio Ciudad de México Explica el problema y la solución, ilustrado con plantas arquitectónicas y una fotografía. Almeida, Héctor F. Residencia en el Pedregal de 11 24 San Ángel Plantas arquitectónicas y fotografías con una breve explicación. Alvarado, Carlos, Conjunto habitacional en 04/05 54 Simón Bali, Jardín Balbuena Ramón Dodero y Planos arquitectónicos, fotos y Germán Herrasti. descripción. Álvarez, Augusto H. Edificio de oficinas en Paseo de 24 52 la Reforma Explica el problema y la solución ilustrado con planos y fotografías. Arai, Alberto T. Edificio de la Asociación México 08 30 – japonesa Explica el problema y el proyecto, ilustrado con planos arquitectónicos y fotografías. Arnal, José María Cripta. 07 38 y Carlos Diener Describen los objetivos del proyecto ilustrado con planta arquitectónica y una fotografía. 11 Autor Artículo No Pg Arrigheti, Arrigo Barrio San Ambrogio, Milán 26 18 Describe el problema y el proyecto, ilustrado con planos y fotografías. Artigas Francisco Residencia en Los Angeles, 12 34 Calif. Explica el proyecto ilustrado con plantas arquitectónicas y fotografías. Artigas, Francisco Mausoleo a Jorge Negrete 09/10 17 Una foto con un pensamiento de Carlos Pellicer. Artigas, Francisco 13 casas habitación 09/10 18 Risco 240, Agua 350, Prior 32 (Casa del arquitecto Artigas), Carmen 70, Agua 868, Paseo del Pedregal 511, Agua 833, Paseo del Pedregal 421, Reforma 2355, Cerrada del Risco 151, Picacho 420, Nubes 309 y Tepic 82 Todas en la Ciudad de México ilustradas con planta arquitectónica y fotografías. -

Chicken Wire and Telephone Calls: on Robert Caro

30 The Nation. December 10, 2012 LBJ PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY/YOICHI OKAMOTO LBJ PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY/YOICHI President Lyndon B. Johnson, October 22, 1968 Chicken Wire and Telephone Calls by THOMAS MEANEY obert Caro has been tracking his great The Years of Lyndon Johnson simply to be always the greediest, most ambi- white whale for thirty years now. As The Passage of Power. tious and ruthless man in the room. with any undertaking of this scale, an By Robert A. Caro. This is a serious criticism, but like the Knopf. 712 pp. $35. aura of legend attaches to the labor. journalistic halo over Caro, it confuses First there is the Ahab-like devotion to post-1960 scholarship. All of this fact- the trappings of his achievement for its Rwith which he has pursued the life of Lyndon hunting and what you might call Method core. Caro has always been more valuable Baines Johnson. In 1977, not long after pub- research has made Caro—who started his as a guide to how power works in postwar lishing his epic biography of Robert Moses, career as a reporter for Newsday—something America in particular than how it works New York City’s master builder, Caro de- of a hero for American journalists: he is the in some general abstract sense. Biography camped to Texas Hill Country for three years guildsman who made good and raised their would not initially seem to be the form best to take in the air of LBJ’s childhood. He spent craft to a level that academics can only envy. -

Designing Cities, Planning for People

Designing cities, planning for people The guide books of Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon Minna Chudoba Tampere University of Technology School of Architecture [email protected] Abstract Urban theorists and critics write with an individual knowledge of the good urban life. Recently, writing about such life has boldly called for smart cities or even happy cities, stressing the importance of social connections and nearness to nature, or social and environmental capital. Although modernist planning has often been blamed for many current urban problems, the social and the environmental dimensions were not completely absent from earlier 20th century approaches to urban planning. Links can be found between the urban utopia of today and the mid-20th century ideas about good urban life. Changes in the ideas of what constitutes good urban life are investigated in this paper through two texts by two different 20th century planners: Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon. Both were taught by the Finnish planner Eliel Saarinen, and according to their teacher’s example, also wrote about their planning ideas. Meurman’s guide book for planners was published in 1947, and was a major influence on Finnish post-war planning. In Meurman’s case, the book answered a pedagogical need, as planners were trained to meet the demands of the structural changes of society and the needs of rapidly growing Finnish cities. Bacon, in a different context, stressed the importance of an urban design attitude even when planning the movement systems of a modern metropolis. Bacon’s book from 1967 was meant for both designers and city dwellers, exploring the dynamic nature of modern urbanity. -

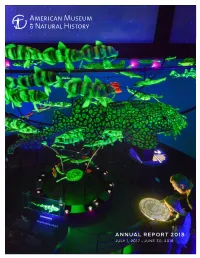

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 JULY 1, 2017 – JUNE 30, 2018 be out-of-date or reflect the bias and expeditionary initiative, which traveled to SCIENCE stereotypes of past eras, the Museum is Transylvania under Macaulay Curator in endeavoring to address these. Thus, new the Division of Paleontology Mark Norell to 4 interpretation was developed for the “Old study dinosaurs and pterosaurs. The Richard New York” diorama. Similarly, at the request Gilder Graduate School conferred Ph.D. and EDUCATION of Mayor de Blasio’s Commission on Statues Masters of Arts in Teaching degrees, as well 10 and Monuments, the Museum is currently as honorary doctorates on exobiologist developing new interpretive content for the Andrew Knoll and philanthropists David S. EXHIBITION City-owned Theodore Roosevelt statue on and Ruth L. Gottesman. Visitors continued to 12 the Central Park West plaza. flock to the Museum to enjoy the Mummies, Our Senses, and Unseen Oceans exhibitions. Our second big event in fall 2017 was the REPORT OF THE The Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth received CHIEF FINANCIAL announcement of the complete renovation important updates, including a magnificent OFFICER of the long-beloved Gems and Minerals new Climate Change interactive wall. And 14 Halls. The newly named Allison and Roberto farther afield, in Columbus, Ohio, COSI Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals will opened the new AMNH Dinosaur Gallery, the FINANCIAL showcase the Museum’s dazzling collections first Museum gallery outside of New York STATEMENTS and present the science of our Earth in new City, in an important new partnership. 16 and exciting ways. The Halls will also provide an important physical link to the Gilder All of this is testament to the public’s hunger BOARD OF Center for Science, Education, and Innovation for the kind of science and education the TRUSTEES when that new facility is completed, vastly Museum does, and the critical importance of 18 improving circulation and creating a more the Museum’s role as a trusted guide to the coherent and enjoyable experience, both science-based issues of our time. -

2020 Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Awards

2020 Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Awards Student Design Competition Brief $25 | per entry at the time of submission $5,000 | First Prize Award Sign up now for more information www.PhiladelphiaCFA.org IMPORTANT DATES August 1, 2019: Full Competition Packet released + Competition opens November 22, 2019: Final date to submit entries February 2020 (date TBD): Awards Ceremony in Philadelphia EDMUND N. BACON URBAN DESIGN AWARDS Founded in 2006 in memory of Philadelphia’s iconic 20th century city planner, Edmund N. Bacon [1910-2005], this annual program honors both professionals and students whose work epitomize excellence in urban design. Each year, a professional who has made significant contributions to the field of urban planning is selected to receive our Edmund N. Bacon Award. In addition, the winners of an international student urban design competition, envisioning a better Philadelphia, are honored with our Edmund N. Bacon Student Awards. The combined awards ceremony is hosted in Philadelphia each February. 2020 STUDENT AWARDS COMPETITION TOPIC THE BIG PICTURE: REVEALING GERMANTOWN’S ASSETS Chelten Avenue is the heart of the Germantown business district in northwest Philadelphia. The most economically diverse neighborhood in the city, Germantown is an African American community which bridges the economically disadvantaged neighborhoods of North Philadelphia to the east with the wealthier Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods to the west. The Chelten Avenue shopping district benefits from two regional rail stations (along different train lines) and one of the busiest bus stops in the city, located midway between the stations. In addition, the southern end of the shopping district is just steps from the expansive Wissahickon Valley Park, one of the most wild places in Philadelphia, visited by over 1 million people each year. -

CONTENIDO Por REVISTA

ÍNDICE de CONTENIDO por REVISTA Arquitectos de México No. 1 Julio de 1956 Autor Artículo No Pg Editores Arquitectos colaboradores 01 11 Lista con más de 600 arquitectos. Editores Sumario 01 12 Editores Dedicatoria 01 13 Breve escrito para dedicar la revista a quienes hacen arquitectura. Rosen, Manuel Casa en el Pedregal de San 01 14 Ángel y casa en Parque Vía Reforma 1990 Planta arquitectónica y fotos exteriores de ambos proyectos, con una breve descripción valorativa. Greenham, Casa en el Pedregal de San 01 21 Santiago Ángel Planta arquitectónica y dos fotos exteriores con una breve descripción. Reygadas, Carlos Casa en Palmas 1105, Lomas 01 22 Planta arquitectónica y fotos exteriores con una breve descripción. De Robina, Ricardo Residencia en el Pedregal y 01 26 y Jaime Ortiz Edificio comercial Monasterio Planta arquitectónica y fotos de la residencia con una breve descripción y fotos del edificio comercial con un comentario de Matías Goeritz acerca del mural: “Mano Codiciosa” en el que describe su significado y proceso creador. Torres, Ramón y Edificio 01 34 Héctor Velázquez Plantas arquitectónicas y fotos del exterior. Velásquez, Héctor, 2 Residencias 01 38 Ramón Torres y Plantas arquitectónicas, fotos y una Víctor de la Lama breve descripción. 11 Autor Artículo No Pg González Rul, Casa en la calle de Damas 139 y 01 42 Manuel casa en Palacio de Versalles 115 La primera con dos fotos exteriores y una breve descripción; la segunda con plantas arquitectónicas, fotos exteriores y una breve descripción. Hernández, Residencia 01 48 Lamberto y Tres fotos. Agustín Hernández Velazco, Luis M. -

Improving Urban Planning in Africa

Improving Urban Planning in Africa By: ERIC JAFFE | NOV 22, 2011 http://www.theatlanticcities.com/design/2011/11/improving-urban-planning-africa/549/ Urbanization is growing at an incredible pace in the global south, but urban planning isn't keeping up. Many planning schools in Africa still promote ideas transferred from the global north. (The master plan of Lusaka, in Zambia, for instance, was based on the concept of the garden city.) As a result, these programs often fail to prepare planners for the problems they will encounter in African cities, such as rapid growth, poverty, and informality — that is, people who pursue livelihoods outside formal employment opportunities. In 2008 the Association of African Planning Schools, a network of 43 institutions that train urban planners, began a three-year effort to reform planning education on the continent. Nancy Odendaal, project coordinator for A.A.P.S. and a planning professor at the University of Cape Town, in South Africa, offers a progress report on this effort in an upcoming issue of the journal Cities. "In order to confront the urbanisation pressures on the continent in all its unique dimensions," she writes, "fundamental shifts are needed in the materials covered in urban training programs and in the methods used to prepare practitioners." Odendaal recently answered some questions about what these shifts entail, and what they might mean for the future of Africa's cities. The aim of A.A.P.S. is to help urban planners in Africa respond to the "special circumstances" of African urbanization, according to your paper. Broadly speaking, what would those be? African urbanization does not follow the "conventional" patterns of industrialization and concomitant job creation in the North, where rapid urban growth was first experienced. -

Naming Power?: Urban Development and Contestation in the Callowhill Neighborhood of Philadelphia

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2020 Naming Power?: Urban Development and Contestation in the Callowhill Neighborhood of Philadelphia Rachel E. Marcus Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the American Studies Commons Repository Citation Marcus, Rachel E., "Naming Power?: Urban Development and Contestation in the Callowhill Neighborhood of Philadelphia" (2020). Honors Papers. 703. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/703 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAMING POWER? Urban Development and Contestation in the Callowhill Neighborhood of Philadelphia ________________________________________________ Rachel Marcus Honors Thesis Department of Comparative American Studies Oberlin College April 2020 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Introduction Naming Power? 4 Methodology 7 Literature Review 11 What Lies Ahead… 15 Chapter One: 1960 Comprehensive Plan to 2035 Citywide Vision The 1960 Comprehensive Plan 17 2035 Citywide Vision 27 Chapter Two: The Rail Park Constructing the Rail Park 34 High Line as Precedent to the Rail Park 40 Negotiating the Rail Park 43 Identifying with the Rail Park 46 Conclusion 51 Chapter Three: The Trestle Inn Marketing and Gentrification 55 Creative Class and Authenticity 57 The Trestle Inn and Authenticity 62 Incentivizing Gentrification 66 Marketing Authenticity 68 Chapter Four: Eastern Tower Introduction 72 Chinatown History 75 Revalorization and Chinatown 83 Racial Triangulation and Chinatown 85 Secondary Source Bibliography 93 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Working on a project like this is so collaborative that this piece of scholarship is as much mine as it is all the people who have helped me along the way. -

Urban Africa – Urban Africans Picture: Sandra Staudacher New Encounters of the Urban and the Rural

7th European Conference on African Studies ECAS 29 June to 1 July 2017 — University of Basel, Switzerland Urban Africa – Urban Africans Picture: Sandra Staudacher New encounters of the urban and the rural www.ecas2017.ch Convening institutions Institutional partners Funding partners ECAS7 Index 3 Welcome 4 Word from the organisers 5 Organisers 6 A* Magazine 7 Programme overview 10 Keynote speakers 12 Hesseling Prize 14 Round Tables 15 Film Sessions 20 Meetings 24 Presentations and Receptions 25 Book launches 26 Panels details (by number) 28 Detailed programme (by date) 96 List of participants 115 Publisher exhibition 130 Practical information 142 Impressum Cover picture: Street scene in Mwanza, Tanzania Picture by Sandra Staudacher. Graphic design: Strichpunkt GmbH, www.strichpunkt.ch. ___ECAS7_CofrenceBook_.indb 3 12.06.17 17:22 4 Welcome ECAS7 ia, India, South Korea, Japan, and Brazil. Currently it has 29 members, 5 associate members and 4 af- filiate members worldwide. Besides the European Conference on African Studies, by far its major ac- tivity, AEGIS promotes various activities to sup- port African Studies, such as specific training events, summer schools, and thematic conferen- ces. Another initiative, the Collaborative Research Groups (CRGs) is creating links between scholars from AEGIS and non-AEGIS centres that engage in collaborative research in new fields. AEGIS also supports the European Librarians in African Stud- ies (ELIAS). A new initiative, relating scholars in Af- rican Studies with social and economic entrepre- neurship is expressed in initiatives such as Africa Works! (African Studies Centre, Leiden) or the I have the great pleasure of welcoming to the 7th Business and Development Forum held just be- European Conference on African Studies ECAS fore ECAS. -

Kenneth Frampton — Megaform As Urban Landscape

/ . ~ - . ' -- r • • 1 ·' \ I ' 1999 Raoul Wallenberg Lecture . __ . Meg~fQrm as Urban .Landscape ~ · ~ · _ · - Kenneth Framrton . l • r ..... .. ' ' '. ' '. ,·, ·, J ' , .. .• -~----------- .:.. Published to commemorate the Raoul Wallenberg Memorial Lecture given by Kenneth Frampton at the College on February 12, 1999. Editor: Brian Carter Design: Carla Swickerath Typeset in AkzidenzGrotesk and Baskerville Printed and bound in the United States ISBN: 1-89"97-oS-8 © Copyright 1999 The University of Michigan A. Alfred T aubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning and Kenneth Frampton, New York. The University of Michigan A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning 2000 Bonisteel Boulevard Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-2069 USA 734 764 1300 tel 734 763 2322 fax www.caup.umich.edu Kenneth Frampton Megaform as Urban Landscape The University of Michigan A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning 7 Foreword Raoul Wallenberg was born in Sweden in 1912 and came to the University of Michigan to study architecture. He graduated with honors in 1935, when he also received the American Institute of Architects Silver Medal. He returned to Europe at a time of great discord and, in 1939, saw the outbreak of a war which was to engulf the world in unprecedented terror and destruction. By 1944 many people, including thousands ofjews in Europe, were dead and in March of that year Hitler ordered Adolph Eichman to prepare for the annihilation ofthejewish population in Hungary. In two months 450,000 Jews were deported to Germany, and most of those died. In the summer of that same year Raoul Wallenberg, who was 32 years old, went to Budapest as the first Secretary of the Swedish Delegation in Hungary. -

Gottlieb on Heller, 'Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia'

H-Urban Gottlieb on Heller, 'Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia' Review published on Thursday, September 19, 2013 Gregory L. Heller. Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. 320 pp. $39.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8122-4490-8. Reviewed by Dylan Gottlieb (Princeton University)Published on H-Urban (September, 2013) Commissioned by Robert C. Chidester In the summer of 2002, Wesleyan University junior Gregory Heller sent Edmund Bacon-- Philadelphia's foremost postwar planner--a letter. Soon, he was sharing lunch with the aging architect, considering an offer to become Bacon's personal archivist. Before the check arrived, Heller had decided to take a year off from college to help Bacon write his memoirs. Heller was twenty. Bacon was ninety-two. Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia is the product of that collaboration. Equal parts history, biography, and urban planning case study, the book's timing is ideal: It is among the first full-length treatments of Bacon, and one of only a handful of monographs on Philadelphia's postwar period. This is surprising, since the city was the locus of some of the era's most imaginative and complex urban design initiatives. As Heller writes, Philadelphia "secur[ed] the second-most federal urban renewal funds, after New York City. In the mid-1960s, no city ... eclipse[d] Philadelphia's national renown for its planning and redevelopment" (p. 2). Indeed, in the following decades, Philadelphia transformed itself from a deindustrializing backwater into a vibrant magnet for creative-class types. -

Overcoming Financial and Institutional Barriers to TOD: Lindbergh Station Case Study

Overcoming Financial and Insitutional Barriers to TOD Overcoming Financial and Institutional Barriers to TOD: Lindbergh Station Case Study Eric Dumbaugh Abstract While transit-oriented development has been embraced as a strategy to address a wide range of planning objectives, from minimizing automobile dependence to im- proving quality of life, there has been almost no examination into the practices that have resulted in the actual development of one. This study examines Atlanta’s Lindbergh Station TOD to understand how a real-world development was able to overcome the substantial development barriers that face these developments. It finds that transit agencies have a largely underappreciated ability to overcome the land assembly and project financing barriers that have heretofore prevented the develop- ment of these projects. Further, because they provide a means from converting capi- tal investment into positive operating returns, this study finds that development projects provide transit agencies with a unique means of overcoming the capital bias in funding apportionment mechanisms. This latter factor will undoubtedly play a key role in increasing the popularity of transit-agency sponsored TOD projects in the future. 43 Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2004 Introduction Transit-oriented development (TOD), which seeks to encourage transit and walk- ing as a travel mode by clustering mixed-use, higher density development around transit stations (Calthorpe 1993), has become popularly embraced as a strategy for mitigating a host of social ills, such as sprawl, automobile dependence, travel congestion, air pollution, and physical health, among others (Belzer and Autler 2002; Cervero et al. 2002; Frank et al.