Lord and Vassal Or Tenant. Relations of the King of Connaught with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland

COLONEL- MALCOLM- OF POLTALLOCH CAMPBELL COLLECTION Rioghachca emeaNN. ANNALS OF THE KINGDOM OF IEELAND, BY THE FOUR MASTERS, KKOM THE EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE YEAR 1616. EDITED FROM MSS. IN THE LIBRARY OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY AND OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN, WITH A TRANSLATION, AND COPIOUS NOTES, BY JOHN O'DONOYAN, LLD., M.R.I.A., BARRISTER AT LAW. " Olim Regibus parebaut, nuuc per Principes faction! bus et studiis trahuntur: nee aliud ad versus validiasiuias gentes pro uobis utilius, qnam quod in commune non consulunt. Rarus duabus tribusve civitatibus ad propulsandum eommuu periculom conventus : ita dum singnli pugnant umVersi vincuntur." TACITUS, AQBICOLA, c. 12. SECOND EDITION. VOL. VII. DUBLIN: HODGES, SMITH, AND CO., GRAFTON-STREET, BOOKSELLERS TO THE UNIVERSITY. 1856. DUBLIN : i3tintcc at tije ffinibcrsitn )J\tss, BY M. H. GILL. INDEX LOCORUM. of the is the letters A. M. are no letter is the of Christ N. B. When the year World intended, prefixed ; when prefixed, year in is the Irish form the in is the or is intended. The first name, Roman letters, original ; second, Italics, English, anglicised form. ABHA, 1150. Achadh-bo, burned, 1069, 1116. Abhaill-Chethearnaigh, 1133. plundered, 913. Abhainn-da-loilgheach, 1598. successors of Cainneach of, 969, 1003, Abhainn-Innsi-na-subh, 1158. 1007, 1008, 1011, 1012, 1038, 1050, 1066, Abhainn-na-hEoghanacha, 1502. 1108, 1154. Abhainn-mhor, Owenmore, river in the county Achadh-Chonaire, Aclionry, 1328, 1398, 1409, of Sligo, 1597. 1434. Abhainn-mhor, The Blackwater, river in Mun- Achadh-Cille-moire,.4^az7wre, in East Brefny, ster, 1578, 1595. 1429. Abhainn-mhor, river in Ulster, 1483, 1505, Achadh-cinn, abbot of, 554. -

Adair, the Surname, 97

INDEX Ballybogey, 73, 220 Adair, the surname, 97 Ballydivity, 99, 127, 128, 129, Aelach, 94, 95, 96 274 Agivey, 101 Ballygalley Castle, 254 Aiken, the surname, 97 Ballylinny, 43, 105, 121,134, Aird Snout, 218 223 Alba, 94 Ballylough House, 99 Ballylough, 125, 127, 128, 131, Albert, the Prince Consort, 120 132, 274 Alexander, Admiral JS, 157 Ballymagarry House, 99 Alexander, James, 220, 222, 232 Ballymena Observer, 152 Alexander, Jim and Dorothy, 16 Ballymoney-Ballycastle Railway, Alexander, Mrs of Garvagh, 204 128 Alexander, Rev Sam, 38, 42, 237 Ballytober, 220 Alexander, the surname, 97 Ballywillin, 38, 92 Anderson, Careen (Hopkins), 40, Banagher, 216 41 Bann, 101, 109, 155, 245, 248 Anderson, Colin Boal, 241 Barbarians, 56 Anderson, Gertie (Kane), 16, 18, 27, 42 Baronscourt, 119, 120 Anderson, Hugh, 112, 177 Barony of Cary, 90 Anderson, Nuala (Gordon), 40, 41 barony, 90, 91 Anderson, Sam, 16, 50 Barry‟s, 43 Bartlett, William Henry, 207, 208, Anderson, the surname, 97 214 Anderson, William, 112 Bassett, George Henry, 191 Ardihannon, 25, 35, 90, 91, 104, 105, 109, 115, 135, 170, 213, 236, Battenburg, Prince Louis of, 229 251 Battle of the Boyne, 58 Armoy, 92, 125, 223, 249, 250, Baxter, David, 153 268 Baxter, Jack, 102, 222 Atkinson, John (Lord Atkinson), Baxter, John and Astrid, 73 151, 159 Baxter, John, 102 Atlee, Clement, 54 Baxter, Noreen (Kane), 16, 236, Auld Lammas Fair, 154 271 aurora borealis, 264 Baxter, the surname, 97 baile, 90 Baynes, TM, 190 Bald, William, 110, 257, 258 Bayview Hotel, 272 Balfour, Gerald, Earl of Balfour, Beach Hotel, 272 145 Beamish, Cecil, 56 Ballintoy, 42, 65, 66, 92, 97, 99, Beamish, Charles Eric St John, 106, 110. -

Heineman Royal Ancestors Medieval Europe

HERALDRYand BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE HERALDRY and BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE INTRODUCTION After producing numerous editions and revisions of the Another way in which the royal house of a given country familiy genealogy report and subsequent support may change is when a foreign prince is invited to fill a documents the lineage to numerous royal ancestors of vacant throne or a next-of-kin from a foreign house Europe although evident to me as the author was not clear succeeds. This occurred with the death of childless Queen to the readers. The family journal format used in the Anne of the House of Stuart: she was succeeded by a reports, while comprehensive and the most popular form prince of the House of Hanover who was her nearest for publishing genealogy can be confusing to individuals Protestant relative. wishing to trace a direct ancestral line of descent. Not everyone wants a report encumbered with the names of Unlike all Europeans, most of the world's Royal Families every child born to the most distant of family lines. do not really have family names and those that have adopted them rarely use them. They are referred to A Royal House or Dynasty is a sort of family name used instead by their titles, often related to an area ruled or by royalty. It generally represents the members of a family once ruled by that family. The name of a Royal House is in various senior and junior or cadet branches, who are not a surname; it just a convenient way of dynastic loosely related but not necessarily of the same immediate identification of individuals. -

Piety, Sparkling Wit, and Dauntless Courage of Her People, Have at Last Brought Her Forth Like

A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics by Thomas D'Arcy McGee In Two Volumes Volume I PUBLISHERS' PREFACE. Ireland, lifting herself from the dust, drying her tears, and proudly demanding her legitimate place among the nations of the earth, is a spectacle to cause immense progress in political philosophy. Behold a nation whose fame had spread over all the earth ere the flag of England had come into existence. For 500 years her life has been apparently extinguished. The fiercest whirlwind of oppression that ever in the wrath of God was poured upon the children of disobedience had swept over her. She was an object of scorn and contempt to her subjugator. Only at times were there any signs of life--an occasional meteor flash that told of her olden spirit--of her deathless race. Degraded and apathetic as this nation of Helots was, it is not strange that political philosophy, at all times too Sadducean in its principles, should ask, with a sneer, "Could these dry bones live?" The fulness of time has come, and with one gallant sunward bound the "old land" comes forth into the political day to teach these lessons, that Right must always conquer Might in the end--that by a compensating principle in the nature of things, Repression creates slowly, but certainly, a force for its overthrow. Had it been possible to kill the Irish Nation, it had long since ceased to exist. But the transmitted qualities of her glorious children, who were giants in intellect, virtue, and arms for 1500 years before Alfred the Saxon sent the youth of his country to Ireland in search of knowledge with which to civilize his people,--the legends, songs, and dim traditions of this glorious era, and the irrepressiblewww.genealogyebooks.com piety, sparkling wit, and dauntless courage of her people, have at last brought her forth like. -

On the Celtic Languages of the British Isles: a Statistical Survey

On the CELTICLANGUAGES ilz the BRITISHISLES; n STATISTICAL SURVEY.By E. Q. RAVENSTEIN,EsQ., F.R.G.S., kc.* [Read before the Statistical Society, 15th April, 1879.1 OF all subjects of statistical inquiry, that relating to the nationality of the inhabitants of one and the same State, is one of the most interesting. In some of the great empires of the continent it is of vital importance. Until the beginning of this century, a process of amalgamation and consolidation had been going on in most countries of Europe, the weaker nationalities adopting the languages of their more powerful neighbours. But the spirit of nationality is abroad now. In its name have been carried on some of the most tremendous wars our age has witnessed, and even the smaller national fractions are loudly asserting their existence. The reign of one universal language appears to be more remote than ever before. It appeared to me that an inquiry into the geographical dis- tribution and numerical strength of the non-English speaking inhabitants of the British Isles might prove of interest to the members of the Statistical Society. Hence this paper. Fortunately, a question of language is not likely in these islands to lead to civil discord or dismemberment. No one dreams of ousting English from the place of vantage it holds, and even though the Irish Home Rulers succeeded in setting up a parliament of their own, its pro- ceedings would have to be carried on in English. Yet, in spite of the comparative insignificance of the Celtic tongues which survive amongst us, this question of race and language abounds in interest. -

File Number Roscommon County Council

DATE : 01/05/2007 ROSCOMMON COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 12:58:37 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 23/04/2007 TO 27/04/2007 FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE M.O. M.O. NUMBER AND ADDRESS TYPE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 05/1684 Harding Wood Properties, R 12/12/2005 Permission Granted for an effluent treatment system with 26/04/2007 PL892/07 36 Fizwilliams Square, raised percolation area, for the demolition of existing Dublin 2 domestic garage and full PLANNING PERMISSION for (1) the extension to nursing home known as Meadowmlands Nursing Home, namely 504.33m2 in floor plan comprising of 13 new bed spaces, 1 day room and a sufficient number of bathrooms and service areas, (2) 410 m2 of new sheltered accommodation (10 units) (only) (3) 120.22 m2 of staff living space together with connection to services and ancillary development (Only). (Application made for the development of an effluent treatment system with raised percolation area, for the demolition of existing domestic garage and full planning permission for 1. the extension to nursing home known as Meadowlands Nursing Home, namely 504.33m2 in floor plan comprising of 13 new bed spaces, 1 day room and a sufficient number of bathrooms and service areas, 2. 575.71m2 of new sheltered accommodation (14units) 3. 120.22m2 of staff living space together with connection to services and ancillary development) at Cloonfad East Td., Cloonfad, Co. Roscommon. 06/1093 Tom & Majarie Leahy, P 16/06/2006 To erect fully serviced dwelling, detached domestic 25/04/2007 PL867/07 4 Summerhill Court, garage, entrance, sewerage treatment facilities, connect Carrick-on-Shannon, to public watermain and all ancillary site works at Co. -

Roscommon County Council Time : 09:35:09 Page : 1 P L a N N I N G a P P L I C a T I O N S Planning Applications Received from 27/11/06 to 01/12/06

DATE : 05/12/2006 ROSCOMMON COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:35:09 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 27/11/06 TO 01/12/06 FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER AND ADDRESS TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 06/2229 Brian Kelly C 27/11/2006 on Ref. No. 02/741 to construct a dwelling house and Clonark proprietary treatment unit at Athlone Cloonark Td Athlone 06/2230 Charles & Gordon Murray P 27/11/2006 to construct slatted shed with calf creep and Bohoroe associated concrete apron at lands at Elphin Ballysundrivan Td Co Roscommon Elphin Co Roscommon 06/2231 Mr Brian Fallon P 27/11/2006 for slatted shed and all associated works at Tullyneeny Tullyneeny Td Dysart Dysart Ballinasloe Ballinasloe Co Roscommon Co Roscommon 06/2232 Irwin Commercial P 27/11/2006 for construction of a single storey extension to the Developments, eastern side of existing building, comprising of Unit 4, 1275m2 of warehouse, 6.75m eaves height and 8.5 Lakeland Enterprise Centre, apex height, together with building signage and Ballydangan, modifications of existing car parking spaces and Athlone, Co Roscommon provision of additonal car parking spaces and all associated site works at Loughlachagh Td Ballydangan Athlone Co Roscommon DATE : 05/12/2006 ROSCOMMON COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:35:09 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 27/11/06 TO 01/12/06 FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. -

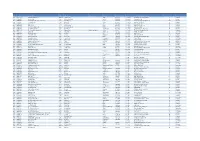

Sector Property Reg Number Account Name Rating Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City/Town Eircode/Postal Code County Owner(S) As It Appears on Register Total No

Sector Property Reg Number Account Name Rating Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City/Town Eircode/Postal code County Owner(s) as it appears on Register Total No. of Bedrooms Proprietor Description Hotel HHS40298 Ballykealey Manor Hotel Approved Rosslare Road Ballon R93 A9K1 Co. Carlow Ballykealey House Events Limited 12 Company Hotel HHS03938 Dinn Ri Hotel 3 Star 22-25 Tullow Street Carlow R93 C8X5 Co. Carlow Flexhaven Limited 10 Company Hotel HHS04319 Mount Wolseley Hotel Spa & Golf Resort 4 Star Mountwolseley Tullow R93 C9H0 Co. Carlow Mount Wolseley Hospitality Limited 143 Company Hotel HHS02987 Seven Oaks Hotel 4 Star Athy Road Carlow R93 V4K5 Co. Carlow Keadeen (Carlow) Ltd 89 Company Hotel HHS04511 Step House 4 Star Main Street Borris R95 V2CR Co. Carlow Sannagate Limited 29 Company Hotel HHS04325 Talbot Carlow 4 Star Portlaoise Road Carlow R93 Y504 Co. Carlow Talbot Hotel Carlow Ltd 84 Company Hotel HHS40376 The Clink Boutique Hotel Approved 38/39 Dublin Street Carlow R93 D7X9 Co. Carlow Slaneygio Limited 18 Company Hotel HHS04124 The Lord Bagenal Inn 4 Star Carlow Road Leighlinbridge R93 E189 Co. Carlow Leighlinbridge Enterprises Limited 39 Company Hotel HHS03495 The Woodford Dolmen Hotel 3 Star Kilkenny Road Mortarstown Upper Carlow R93 N207 Co. Carlow The Woodford Dolmen Hoel Ltd 81 Company Hotel HHS01727 Bailie Hotel 2 Star Main Street Bailieborough A82 T6C6 Co. Cavan Mr Patrick McEnaney 16 Sole Trader Hotel HHS04159 Breffni Arms Hotel 3 Star Main Street Arva H12 CP38 Co. Cavan Gildoran Ltd 12 Company Hotel HHS03438 Cabra Castle Hotel 4 Star Cormey Kingscourt A82 EC64 Co. -

The Galweys & Gallweys of Munster

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/detaiis/galweysgailweysoOObiac The Galweys & Gallweys of Munster by Sir Henry Blackall Updated & Computerised by Andrew Galwey & Tim Gallwey Revised issue 2015 Vinctus sed non Victus Vincit Veritas PUBLIC VERSION N.B. May be put into the public domain. See over. 1 CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE, USE, COPYING & TRANSMISSION Risk of Identity Theft This version is for general usage since only the year of birth, marriage or death is given i.e. no day or month, for people born after 1914, married after 1934 or died after 1984. It is available in some publicly accessible locations such as the library of the Irish Genealogical Research Society, National Archive of Ireland, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, Cork County Library (Reference section). National Library of Ireland, and Clonakilty Library. There is also a FAMILY VERSION which is restricted to family members only, as it has full details of day, month and year of birth, marriage and death, where known, to facilitate identification of individuals when located. Such information is not provided in this version due to the risk of identity theft. Open Source The information contained herein has been collated from many sources. The bulk comes from copies of the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society (JCHAS) which owns the copyright. Other material has been published in The Irish Genealogist and further information has been gleaned from the internet, requests to family members, personal archives, and so on. This is a living document and is distributed subject to the conditions of the copyleft convention (GNU GENERAL PUBLIC LICENSE See http://fsf.org ) whereby there is no charge for copying or distributing. -

Colonial Families and Their Descendants

M= w= VI= Z^r (A in Id v o>i ff (9 VV- I I = IL S o 0 00= a iv a «o = I] S !? v 0. X »*E **E *»= 6» = »*5= COLONIAL FAMILIES AND THEIR DESCENDANTS . BY ONE OF THE OLDEST GRADUATES OF ST. MARY'S HALL/BURLI^G-TiON-K.NlfJ.fl*f.'< " The first female Church-School established In '*>fOn|tSe<|;, rSJatesi-, which has reached its sixty-firstyear, and canj'pwß^vwffit-^'" pride to nearly one thousand graduates. ; founder being the great Bishop "ofBishop's^, ¦* -¦ ; ;% : GEORGE WASHINGTON .DOANE;-D^D];:)a:i-B?':i^| BALTIMORE: * PRESS :OF THE.SUN PRINTING OFFICE, ¦ -:- - -"- '-** - '__. -1900. -_ COLONIAL FAMILIES AND THEIR DESCENDANTS , BY ONE OF THE OLDEST GRADUATES OF - ST. MARY'S HALL, BURLINGTON, N. J. " The first female Church-School established in the United.States, which has reached its sixty-first year, and can point with ; pride to nearly one thousand graduates. Its.noble „* _ founder being the great Bishop ofBishops," GEORGE WASHINGTON DOANE, D.D., LL.D: :l BALTIMORE: PRESS "OF THE SUN PRINTING OFFICE, igOO. Dedication, .*«•« CTHIS BOOK is affectionately and respectfully dedicated to the memory of the Wright family of Maryland and South America, and to their descendants now livingwho inherit the noble virtues of their forefathers, and are a bright example to "all"for the same purity of character "they"possessed. Those noble men and women are now in sweet repose, their example a beacon light to those who "survive" them, guiding them on in the path of "usefulness and honor," " 'Tis mine the withered floweret most to prize, To mourn the -

An Insight Into the Area We Live in Vol

An initiative of Ballinasloe Area Community Development Ltd. To get in touch with Ballinasloe Life online, visit us here: www.ballinasloeenterprisecentre.ie www.facebook.com/BallinasloeLife AN INSIGHT INTO THE AREA WE LIVE IN Vol. 10 Issue 3: Aug' ‘20 - Sep' ‘20 Photo by Robert Riddell NIAMH KELLY ERIC NAUGHTON NEW CEO OF OUR UN DIPLOMAT ROADRUNNER FOR CHARITY CREDIT UNION Ballinasloe - Gateway To The West www.ballinasloe.ie Gullane’s Hotel & CONFERENCE CENTRE We are delighted to announce that we are officially back opEn For BuSinESS Unfortunately, we are opening under new guidelines and restrictions that are put in place due to Covid -19 so some things will have slightly changed. What will not have changed will be the warm friendly welcome and delicious homemade food that is synonymous with Gullane’s. We are really looking forward to welcoming you all back. To book your meal or event contact us on 09096 42220 or email [email protected] Main Street, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway T: 090 96 42220 F: 090 96 44395 E: [email protected] Visit our website gullaneshotel.com REAMHRA Welcome to Volume 10 issue 3 Well it’s been a testing 2 months of truly a strange summer. Huge Autumn and we congratulate and welcome to Pauric O’Halloran thanks again to all our local subscribers who renewed their and Paul Walsh who will be the new principals of our town’s financial commitment to keeping this flame lit. two schools. We managed to profile Paul, but between holiday COVID is going to change a lot. Many firms felt they had a fighting commitments it was not possible in this edition to catch up with chance by hanging on till the street enhancement was finished - Pauric – we will do so in the next and we will also chat and look will find the next part of the uphill struggle just too much. -

Database of Irish Historical Statistics Datasets in the Irish Database

Database of Irish Historical Statistics Datasets in the Irish Database Agricultural Statistics: Agriculture Crops Stock Census Statistics Age Housing Population Language Literacy Occupations Registrar General Statistics Vital Statistics Births Marriages Deaths Emigration Miscellaneous Statistics Famine Relief Board of Works Relief Works Scheme Housing Spatial Areas Barony Electoral Division Poor Law Union Spatial Unit Table Name Barony housing_bar Electoral Divisions housing_eldiv Poor Law Union housing_plu Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Poor Law Union plu_id (spatial code book) Poor Law Union plu_county_id (spatial code book) Housing (Barony) Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Belfast Town/City (Co.