Promotion of Environmental Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

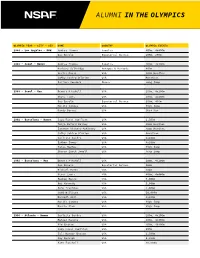

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA MEN's ATHLETICS 1992-93 All-Sports Report

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MEN'S ATHLETICS 1992-93 All-Sports Report :~en's Intercollegiate Athletics turned in 10-meter platform diving national title and Martin another outstanding year in 1992-93 with Eriksson won the NCAA indoor pole vault crown. ' individual student-athletes and athletic teams achieving exceptional success in the classroom and Minnesota athletes also achieved well in the class in the athletic arena. mom. Fourteen Golden Gopher swimmers and divers were named to the 1992-93 Academic All-Big Ten team. Three teams won conference championships. The ten There were 10 in track and field, eight in football, seven nis and baseball (tournament) squads won Big Ten in baseball, four in hockey, four in golf, three in gymnas crowns, while the hockey team captured the WCHA tics, two in cross country and basketball and one in ten Tournament. Gaining seconds were gymna.".ltics and nis. The total of 55 honorees is a new U of M record. In swimming and diving. Golf was third, track and field addition to being honored as the Academic All-American third outdoors and fourth indoors, wrestling fourth and of the Year, Roethlisbergcr was joined by Eriksson on the basketball fifth. Only two Golden Gopher teams, cross GTE Academic All-America Men's At-Large First Team. country and football, failed to finish in the Big Ten's first High jumper Matt Burns was named to the GTE division. Academic All-America At-Large Third Team, and Darren Schwankl was honored on the GTE Academic Winning team championships were Coach Doug All-America Baseball Third Team. -

Comprehensive Framework for Describing Interactive Sound Installations: Highlighting Trends Through a Systematic Review

Multimodal Technologies and Interaction Article Comprehensive Framework for Describing Interactive Sound Installations: Highlighting Trends through a Systematic Review Valérian Fraisse 1,2,* , Marcelo M. Wanderley 1,2 and Catherine Guastavino 1,2,3 1 Schulich School of Music, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 1E3, Canada; [email protected] (M.M.W.); [email protected] (C.G.) 2 Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT), Montreal, QC H3A 1E3, Canada 3 School of Information Studies, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 1X1, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-(0)645500305 Abstract: We report on a conceptual framework for describing interactive sound installations from three complementary perspectives: artistic intention, interaction and system design. Its elaboration was informed by a systematic review of 181 peer-reviewed publications retrieved from the Scopus database, which describe 195 interactive sound installations. The resulting taxonomy is based on the comparison of the different facets of the installations reported in the literature and on existing frameworks, and it was used to characterize all publications. A visualization tool was developed to explore the different facets and identify trends and gaps in the literature. The main findings are presented in terms of bibliometric analysis, and from the three perspectives considered. Various trends were derived from the database, among which we found that interactive sound installations Citation: Fraisse, V.; Wanderley, are of prominent interest in the field of computer science. Furthermore, most installations described M.M.; Guastavino, C. Comprehensive in the corpus consist of prototypes or belong to exhibitions, output two sensory modalities and Framework for Describing Interactive include three or more sound sources. -

Encyclopedia of Metagenomics

Encyclopedia of Metagenomics Karen E. Nelson Editor Encyclopedia of Metagenomics Genes, Genomes and Metagenomes: Basics, Methods, Databases and Tools With 216 Figures and 64 Tables Editor Karen E. Nelson J. Craig Venter Institute Rockville, MD, USA ISBN 978-1-4899-7477-8 ISBN 978-1-4899-7478-5 (eBook) ISBN 978-1-4899-7479-2 (print and electronic bundle) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4899-7478-5 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014954611 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

73Rd Management Board Doc

European Environment Agency 73rd Management Board Doc. EEA/MB/73/02-final 24 June 2015 MINUTES OF THE 72nd MANAGEMENT BOARD MEETING 18 March 2015 Approved by the Chair of the Management Board on 24 June 2015 SIGNED ______________________________ Elisabeth Freytag-Rigler Chair, EEA Management Record of proceedings: The Chair, Elisabeth Freytag-Rigler, opened the meeting by welcoming new Board members and presenting apologies on behalf of those members unable to attend. The tabled documents were acknowledged during the course of the meeting (list included after the agenda in Annex 1). Final agenda: Annex 1 Attendance list: Annex 2 Action list: Annex 3 Decision list: Annex 4 ITEMS A 1-2 FOR DECISION Item A1 Adoption of draft agenda The Board adopted the agenda (Doc. EEA/MB/72/A1rev.1) without changes. Further to that, the Chair proposed to continue with the current agenda structure but keeping the old numerical order, instead of a combination of letters and numbers. Item A2 Adoption of the 71st Management Board minutes, 19 November 2014 The Board adopted the minutes of the 71st Management Board meeting held on 19 November 2014 with a minor change. The final version (Doc. EEA/MB/72/02-final) of the minutes is available on Forum. The members also took note of the tabled MB rolling action list. ITEMS B 1-5 FOR INFORMATION Item B.1 Draft minutes of the 65th Bureau meeting, 3 February 2015 The Board members took note of the draft minutes of the 65th Bureau meeting held on 3 February 2015. Item B.2 Update by the Chair (oral) The Chair mentioned the following points: - Successful completion of 3 MB written procedures since the last MB meeting: o Staff implanting rules on new working time a derogation of SI CA; o 4th amendment to the 2014 Budget (re Copernicus); o MB response to the NFP letter (re Dimesa workshop). -

Etn1992 16 NCAA

(ECar) 45.45; 6. *Duaine Ladejo' (Tx) 45.63; 7. Jason Rouser (Ok) 45.74 ; 8. *Anthuan Maybank (la) 45.87. HEATS (June 3, qualify 3+4): 1-1. Minor e 45.05 =PR (=7, x WJ; 5, x AJ); 2. Ladejo' '------- 45.25 ; 3. Irvin 45.44; 4. Seibert Straughn ' 45.70 ; 5. *Ethridge Green 45.75; 6. **Dustin James (UCI) 47.00. 11-1.Watts 44.77 ; 2. Miller 45.60; 3. Frankie Atwater 45.78; 4. Joel McCray (UTA) 45.82; 5. Alan Turner (In) 46.93. 111-1.Rouser 45.73; 2. Mills 46.13; 3. **Forrest Johnson 46.15; 4. *Anthony Wil son' (NnAz) 46.17; 5. *Wesley Russell ,,,:· #Pfll?Wifti@;~!:i#fu~~:y#.f~tttkk ~ ~W:N:;;:MfufuffilliV~feNj?== (Clem) 46.42. ''·················=··=:=:=:•:=:::.:::::::::=·=•:•···"•■■--■■' ·················•-:,:,•-•,• ::i:f!:ff!/:i:!:\:!:!{tf~l::(:::::::: IV-1. Hannah 45.81; 2. Maybank 45.84; 3. •~a_nny Fredericks (Bay) 46.01; 4. *Corey W1ll1ams(Bay) 46.11; 5. Will Glover (NnAz) 48.58; ... dnf-**Solomon Amegatcher' (Al). SEMIS (June 5, qualify 2+4): 1-1. Minor NCAA Championships • 44.75 (=4, x WJ; 4, x AJ); 2. Rouser 44.92; 3. Maybank 45.27; 4. Green 45.50; 5. Miller Austin, Texas , June 3-6; hot and humid W; =5, =8 C) (MR); 2. Kayode' 10.17; 3. 45.69; 6. Atwater 45.80; 7. Fredericks 46.08· (85°-90°), ~iel~s 10.23; 4. ~enderson 10.32; 5. Akogy 8. McCray 46.10. ' Attendance: 7000 (6/6). Iram 10.34; 6. Hill 10.43; 7. Eregbu' 10.43; 11-1.Watts 44.56; 2. -

And Scientists Immediate Past President 131

LETTER FROM SCIENTISTS TO THE EU PARLIAMENT REGARDING FOREST BIOMASS (updated January 11, 2018) To Members of the European Parliament, As the European Parliament commendably moves to expand the renewable energy directive, we strongly urge members of Parliament to amend the present directive to avoid expansive harm to the world’s forests and the acceleration of climate change. The flaw in the directive lies in provisions that would let countries, power plants and factories claim credit toward renewable energy targets for deliberately cutting down trees to burn them for energy. The solution should be to restrict the forest biomass eligible under the directive to residues and wastes. For decades, European producers of paper and timber products have generated electricity and heat as beneficial by-products using wood wastes and limited forest residues. Since most of these waste materials would decompose and release carbon dioxide within a few years, using them to displace fossil fuels can reduce net carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere in a few years as well. By contrast, cutting down trees for bioenergy releases carbon that would otherwise stay locked up in forests, and diverting wood otherwise used for wood products will cause more cutting elsewhere to replace them. Even if forests are allowed to regrow, using wood deliberately harvested for burning will increase carbon in the atmosphere and warming for decades to centuries – as many studies have shown – even when wood replaces coal, oil or natural gas. The reasons are fundamental and occur regardless of whether forest management is “sustainable.” Burning wood is inefficient and therefore emits far more carbon than burning fossil fuels for each kilowatt hour of electricity produced. -

457712 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..47

Springer Proceedings in Complexity Springer Proceedings in Complexity publishes proceedings from scholarly meetings on all topics relating to the interdisciplinary studies of complex systems science. Springer welcomes book ideas from authors. The series is indexed in Scopus. Proposals must include the following: – name, place and date of the scientific meeting – a link to the committees (local organization, international advisors etc.) – scientific description of the meeting – list of invited/plenary speakers – an estimate of the planned proceedings book parameters (number of pages/ articles, requested number of bulk copies, submission deadline) Submit your proposals to: [email protected] More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11637 Clemens Mensink • Wanmin Gong • Amir Hakami Editors Air Pollution Modeling and its Application XXVI 123 Editors Clemens Mensink Wanmin Gong VITO NV Environment and Climate Change Canada Mol, Belgium Science and Technology Branch Toronto, ON, Canada Amir Hakami Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Carleton University Ottawa, ON, Canada ISSN 2213-8684 ISSN 2213-8692 (electronic) Springer Proceedings in Complexity ISBN 978-3-030-22054-9 ISBN 978-3-030-22055-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22055-6 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Fair and Sustainable Taxation

H2020-EURO-SOCIETY-2014 WWW.FAIR-TAX.EU FAIRTAX FairTax is a cross-disciplinary four year H2020 EU project aiming to CONFERENCE PROGRAMME produce recommendations on how fair and sustainable taxation Fair and Sustainable Taxation and social policy reforms can increase the economic stability of EU member states, promoting Brno, March 9th- 10th, 2017 economic equality and security, enhancing coordination and harmonisation of tax, social inclusion, environmental, special session of the conference legitimacy, and compliance measures, support deepening of Enterprise and Competitive Environment the European Monetary Union, and expanding the EU’s own 2017 organized by Mendel University in Brno resource revenue bases. Under the coordination of Umeå University (Sweden), comparative and international policy fiscal Organizers: experts from eleven universities in Mendel University in Brno (Czech Republic) six EU countries and three non-EU Austrian Institute of Economic Research WIFO Vienna countries (Brazil, Canada and (Austria). Norway) contribute to FairTax Research. The project is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Scientific comitee: research and innovation Giacomo Corneo (FU Berlin), Eva Eberhartinger (University of programme 2014-2018, grant Business and Economics Vienna), Friedrich Heinemann (ZEW Agreement FairTax 649439 Mannheim), Inge Kaul (Global Policy Studies, Hertie School of Governance), Jacques Le Cacheux (OFCE), Mikulas Luptacik (University of Bratislava), Sabine Kirchmayr-Schliesselberger (University of Vienna), Michael -

International Business in an Unsettling Political and Economic Environment

International Business in an Unsettling Political and Economic Environment Copenhagen, Denmark June 24-27, 2019 Program Chair: Maria Tereza Leme Fleury Fundação Getulio Vargas BUSINESS IN SOCIETY CBS is a strong, international institution with a distinctive business university profile. Our main task is to produce knowledge and new thinking to companies and organisations, to the next generation of business leaders and to society at large through research and education. CBS' research profile covers a broad subject area within the social sciences and humanities. The academic breadth reflects a societal need to understand business issues in a broader social, political and cultural context. CBS benefits immensely from a student body that is highly motivated in terms of academic learning and extracurricular activities. CBS’ students are a significant strength of our university, bringing entrepreneurial spirit and great vitality to our activities. Photo: Bjarke MacCarthy Table of Contents AIB President’s Letter . 2 Host School Welcome . 3 Letter from the Program Chair . 4 AIB 2019 Conference Sponsors . 5 AIB 2019 Conference Program Committee . .. 7 AIB 2019 Reviewers . 8 General Conference Information . 18 Get the AIB 2019 Copenhagen Mobile App! . 18 Meeting Venues and Maps . 19 A Visual Insight into AIB 2019 . 22 AIB 2019 in Numbers . 23 AIB 2019 Pre-Conference Overview . 24 AIB 2019 Program Overview . 25 AIB Fellows 2019 International Executive of the Year . 26 AIB Fellows 2019 International Educator of the Year . 27 AIB Fellows 2019 John Fayerweather Eminent Scholar . 28 AIB 2019 Program Awards . 29 AIB 2019 - Meet an AIB Fellow . 33 AIB 2019 - Meet a Journal Editor . 34 AIB 2019 - Teaching Cafés . -

Final Report 1995-2005

Final Report 1995-2005 ASTEC Final Report 1995-2005 This document including cover and appendices as pdf file. Contents Summary Sammanfattning Facts about partners, finances and organisation The Centre Development over 10 years Technical and scientific results Final words Statements form ASTEC industrial partners Appendix 1 ASTEC Publications 1995-2007 Appendix 2 Business ratios 1995-2007 Appendix 3 Projects, their acronyms, names, leaders, goals, time period, volume and publication rate. Appendix 4 Theses made in ASTEC projects and the position and affiliation of the former students in September 2007 Tables and figures Table A. The industrial participation in ASTEC during 1995-2005. Table B. Each partners contribution to ASTEC Table C. Board members during 1995-2005 Table D. Scientific advisory board Summary ASTEC (Advanced Software Technology) was a competence centre, which focused on advanced tools and techniques for software development. Development of software accounts for a significant part of the costs in the construction of a number of important products, such as communication systems, transportation and process control systems, of Swedish industry. ASTEC's vision were that software should be developed using high-level specification and programming languages, supported by powerful automated tools that assist in specification, analysis, validation, simulation, and compilation. ASTEC has conducted pre-competitive and industrially applicable research that contributed to fulfil this vision, built up a concentrated research environment, and been a forum for contacts and exchange of ideas between academia and industry. Four primary examples of ASTEC results are: 1. The High Performance Erlang compiler system: this tools is now widely used in the telecommunication industry, and its importance will grow in the future. -

Swedish Trade and Trade Policies Towards Lebanon 1920-1965

Swedish trade and trade policies towards Lebanon 1920-1965 Ahmad Hussein Department of Economic History ISBN: 978-91-7459-144-6 ISSN: 1653-7475 Occasional Papers in Economic History No. 17/2011 Licentiate Thesis Occasional Papers in Economic History No. 17, 2011 © Ahmad Hussein, 2011 Department of Economic History S-901 87 Umeå University www.umu.se/ekhist 2 Abstract This licentiate thesis examines the development of Swedish–Lebanese trade relations and the changes of significance for Swedish trade towards Lebanon during the period 1920-1965. The aim of the study is to explore how Sweden as representing a small, open Western economy could develop its economic interests in the emerging Middle East market characterised both by promising economic outlooks, and a high degree of political instability during the age of decolonisation, Cold War logic, and intricate commercial and geo-political factors. The study shows that the Swedish trade with Lebanon was very small during the Interwar period. It was neither possible to find any formal Swedish-Lebanese trade agreements before 1945. In the Post- War period, the promotion of Swedish trade and trade policies towards Lebanon witnessed more interests from the both parties. Two categories of explanations were found for the periods of 1946-53 and 1954-65 respectively. In the first period the Swedish-Lebanese trade developed in a traditional direction with manufactured goods being exported from Sweden and agricultural products being exported from Lebanon. Furthermore, there were no trade agreements between the two countries. In the second period, several Lebanese attempts were made to conclude bilateral trade agreement with Sweden in hope to change the traditional trade direction, and to improve the Lebanese balance of trade.