Howdy Modi”: a Diplomatic Tour De Force Superimposed on US-India Bilateral Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 November 2019: PIB Summary & Analysis HADR Exercise TIGER TRIUMPH 6Th World Congress on Rural and Agricultural Finance

12 November 2019: PIB Summary & Analysis HADR Exercise TIGER TRIUMPH Context: The maiden India - US joint tri-services Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Exercise named ‘TIGER TRIUMPH’ is scheduled to be held in November 2019 for 9 days. About HADR Exercise TIGER TRIUMPH: TIGER TRIUMPH is the first joint Indo-US Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) exercise. It is aimed at developing interoperability for conducting HADR operations. Participating teams from India: o Indian Naval ships Jalashwa, Airavat and Sandhayak o Indian Army troops from 19 Madras and 7 Guards o Indian Air Force MI-17 helicopters and Rapid Action Medical Team (RAMT) Participating teams from the USA: o US Navy Ship Germantown o Troops from US Third Marine Division It is an exercise carried out on the Eastern coast of India starting with the Harbour Phase at Visakhapatnam. Personnel from both navies would participate in training visits, subject matter expert exchanges, sports events and social interactions. After this phase, the ships, with troops embarked, would sail for the Sea Phase and undertake maritime, amphibious and HADR operations. On reaching the HADR area at Kakinada, the landing of Relief Forces would be undertaken to the Exercise scenario. At the HADR Exercise Area, a Joint Command and Control Centre would be established jointly by the Indian Army and US Marines. The IAFRAMT and the US Navy Medical Team would establish a Medical Facility Camp for providing medical aid to victims, who would have been previously evacuated by road and air to the Camp. 6th World Congress on Rural and Agricultural Finance Context: The 6th World Congress on Rural and Agricultural Finance was inaugurated in New Delhi. -

Exercise Tiger Triumph''

www.gradeup.co 25th September 2019 1. India-US Tri-Services ''Exercise Tiger Triumph'' • India and the United States are set to hold their first tri-services exercise code-named "Tiger Triumph" at Visakhapatnam and Kakinada in November this year. • India-US tri-services ''Exercise Tiger Triumph'' is being organised under the aegis of the headquarters of the Integrated Defence Staff. • Final Planning Conference (FPC) for India-US Tri-Services Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief (HADR) concluded at Headquarters Eastern Naval Command on September 20. • For the first time, the US and India will be holding the tri-service military exercise. India earlier conducted such tri-service exercise with Russia. Topic- GS-3- Defence Source- NDTV 2. Gandhi Solar Park • Prime Minister Narendra Modi along with other world leaders inaugurated the Gandhi Solar Park at the United Nations (UN) headquarters on the occasion of Gandhi's 150th birth anniversary. • It is 50 kWh roof-top solar park has 193 solar panels—each representing a member of the multilateral body. Related Information • Recently Prime Minister Narendra Modi was conferred the "Global Goalkeeper" award by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. Topic- GS Paper 2 –Governance Source- AIR 3. Krishi Kisan App • Union Minister for Agriculture and Farmers Welfare has launched Krishi Kisan App for Geo Tagging’ in New Delhi. About App • It will provide farmers with the information of the best demonstration of high-yielding crops and seeds in their nearby area. • This application helps to demonstrate best practices of cultivation to other farmers so that this will help other farmers also to adopt these methods. -

Joint Military Exercises Itary Exercises

YEARLY CURRENT AFFAIRS 2019 JOINT MILITARY EXERCISES - ARMY, NAVY & AIR FORCE IMBEX 2019 - India-Myanmar bilateral army exercise held at Chandimandir, Chandigarh in January 2019. IAFTX - India Africa Field Training Exercise held in Pune, Maharasthra from 18th - 27th March 2019. Exercise Rahat - Joint Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief Exercise (Indian Army) held in Jaipur, Rajasthan in February 2019. Exercise Topchi - Indian army demonstrated its artillery firepower, aviation and surveillance capacity, held in Nashik,Maharashtra in February 2019. Exercise Vayu Shakti - Indian Air Force conducted mega exercise. Advanced Light Helicopter (ALP) and the Akash surface-to-air missile were deployed in military exercise for the first time at Pokhran, Rajasthan Mainamati Maitree Exercise 2019 - India’s BSF and Bangladesh’s Border Guards Bangladesh, held in Agartala, Tripura in March 2019. Sampriti-2019 - India and Bangladesh military exercise held at Tangail, Bangladesh in March 2019. Red Flag 2019 - Air forces from United States, the United Arab Emirates, Belgium, the Netherlands, Singapore and Saudi Arabia, held in United States. Exercise Al Nagah III - India and Oman military exercise held at Jabel Al Akhdar Mountains in Oman in March 2019. AFINDEX-19 - Indian Army and 16 African nations military exercise held in Pune, Maharashtra in March 2019. MITRASHAKTI – VI - Indian and Sri Lanka Army exercise held in Diyatalawa in Sri Lanka in March 2019. AUSINDEX 19 - India and Australia military exercise held in Vishakhapatnam, Andhra pradesh in April 2019. African Lion 2019 - Morocco and US military exercise held in Marcco in April 2019. Bold Kurukshetra 2019 - India and Singapore military exercise held at Jhansi’s Babina Cantonment, Uttar Pradesh in April 2019. -

Testbook Live Course Capsules

Useful Links Joint Military Ex- ercises 1 Useful Links In a Joint Military Exercise, a country displays its Military strength be it through weapons or through the showcase of soldiers training it is an important point of International Rela- tions where the country engages in Military Diplomacy in a show of strength. India over the years has participated in a number of Joint Military Exercises with countries across the globe and our neighbours. The Joint Military Exercises are held in different places and in- volve different parts of the military and include the Army, Navy, and Air Force. Often shown as a sign of strength and solidarity, it also allows the military personnel of the countries in- volved in the Military Exercises to gain valuable information on the field and also learn new tactics that are suitable for various situations if it comes in reality. This is an important top- ic that might be asked in the General Awareness section of competitive exams like SSC, SSC CGL, IBPS PO, and others. It can also be asked in Defence Exams like NDA. What is Joint Military Exercise Joint Military Exercise can be seen as a form of engagement of the various organs of the Military in an Exercise with different countries. It can be one country or multiple countries. It is also a showcase of the military strength of the country and tries to send out a message to other countries. It is also a form of Diplomacy, often given the term of Military Diploma- cy. They can be divided into two types, namely: i) Bilateral Exercise: Bilateral Exercise as the name suggests, is the military exercise that takes place between two countries. -

India-U.S. Relations

India-U.S. Relations July 19, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46845 SUMMARY R46845 India-U.S. Relations July 19, 2021 India is expected to become the world’s most populous country, home to about one of every six people. Many factors combine to infuse India’s government and people with “great power” K. Alan Kronstadt, aspirations: its rich civilization and history; expanding strategic horizons; energetic global and Coordinator international engagement; critical geography (with more than 9,000 miles of land borders, many Specialist in South Asian of them disputed) astride vital sea and energy lanes; major economy (at times the world’s fastest Affairs growing) with a rising middle class and an attendant boost in defense and power projection capabilities (replete with a nuclear weapons arsenal and triad of delivery systems); and vigorous Shayerah I. Akhtar science and technology sectors, among others. Specialist in International Trade and Finance In recognition of India’s increasingly central role and ability to influence world affairs—and with a widely held assumption that a stronger and more prosperous democratic India is good for the United States—the U.S. Congress and three successive U.S. Administrations have acted both to William A. Kandel broaden and deepen America’s engagement with New Delhi. Such engagement follows decades Analyst in Immigration of Cold War-era estrangement. Washington and New Delhi launched a “strategic partnership” in Policy 2005, along with a framework for long-term defense cooperation that now includes large-scale joint military exercises and significant defense trade. In concert with Japan and Australia, the Liana W. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks with Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India at A

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks With Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India at a "Howdy, Modi: Shared Dreams, Bright Futures" Rally in Houston, Texas September 22, 2019 Prime Minister Modi. Good morning, Houston. Good morning, Texas. Good morning, America. Greetings to my fellow Indians in India and around the world. Friends, this morning we have a very special person with us. He needs no introduction. His name is familiar to every person on the planet. His name comes up in almost every conversation in the world on global politics. His every word is followed by tens of millions. He was a household name and very popular even before he went on to occupy the highest office in this great country. From CEO to Commander in Chief, from boardrooms to the Oval Office, from studios to global stage, from politics to the economy and to security, he has left a deep and lasting impact everywhere. Today he is here with us. It is my honor and privilege to welcome here, in this magnificent stadium and magnificent gathering—and I can say I had a chance to meet him often, and every time, I found the friendliness, warmth, energy—the President of the United States of America, Mr. Donald Trump. This is extraordinary. This is unprecedented. Friends, as I told you, we have met a few times. And every time, he has been the same warm, friendly, accessible, energetic, and full of wit. I admire him for something more: his sense of leadership, a passion for America, a concern for every American, a belief in American future, and a strong resolve to make America great again. -

U.S. DEPARTMENT of STATE Office of the Spokesperson for Immediate Release

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Spokesperson For Immediate Release FACT SHEET October 25, 2020 SECRETARY POMPEO TRAVELS TO INDIA TO ADVANCE U.S.-INDIA COMPREHENSIVE GLOBAL STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP “Let's seize this moment to deepen cooperation between two of the world’s greatest democracies.” – U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, July 22, 2020 Secretary Michael R. Pompeo will travel to New Delhi, India, October 26-27, 2020, where he and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will meet with External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar and Defense Minister Rajnath Singh for the U.S.-India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue. Secretary Pompeo will also meet with Prime Minister Modi and hold discussions with other government and business leaders on ways to advance the U.S.-India Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership. THE U.S.-INDIA RELATIONSHIP: ROOTED IN DEMOCRATIC TRADITIONS AND GROWING IN NEW STRATEGIC DIMENSIONS The United States and India have a strong and growing bilateral relationship built on shared values and a commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific. As the world’s oldest and largest democracies, the United States and India enjoy deeply rooted democratic traditions. The growth in the partnership reflects a deepening strategic convergence on a range of issues. Our cooperation is expanding in important areas including health, infrastructure development, energy, aviation, science, and space. Holding the third U.S.-India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue in just over two years demonstrates high-level commitment to our shared diplomatic and security objectives. President Trump made a historic visit to India earlier this year, speaking in Ahmedabad before over 100,000 people. -

India's Military Bilateral & Multilateral Exercises in 2019

A Compendium Vivekananda International Foundation India’s Military Bilateral & Multilateral Exercises in 2019 A Compendium © Vivekananda International Foundation 2020 Published in 2020 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org ISBN: 978-81-943795-8-4 Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Contents Foreword .............................................................................. 7 BILATERAL EXERCISES .................................................. 9 Australia ............................................................................................ 9 AUSINDEX, Vishakhapatnam, India ......................................................................... 9 Bangladesh ...................................................................................... 10 SAMPRITI VIII, Tangail, Bangladesh ..................................................................... 10 China .............................................................................................. 12 HAND IN HAND 2019, Foreign Training Node, Umroi, Meghalaya, India ........... 12 GARUDA VI, Mont de Marsan, France .................................................................. -

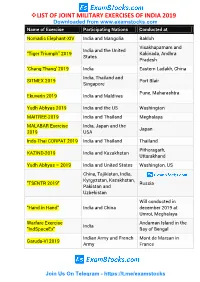

List of Joint Military Exercises of India 2019

LIST OF JOINT MILITARY EXERCISES OF INDIA 2019 Downloaded from www.examstocks.com Name of Exercise Participating Nations Conducted at Nomadic Elephant-XIV India and Mangolia Bakloh Visakhapatnam and India and the United “Tiger Triumph” 2019 Kakinada, Andhra States Pradesh ‘Chang Thang’ 2019 India Eastern Ladakh, China India, Thailand and SITMEX 2019 Port Blair Singapore Pune, Maharashtra Ekuverin 2019 India and Maldives Yudh Abhyas 2019 India and the US Washington MAITREE-2019 India and Thailand Meghalaya MALABAR Exercise India, Japan and the Japan 2019 USA Indo-Thai CORPAT 2019 India and Thailand Thailand Pithoragarh, KAZIND-2019 India and Kazakhstan Uttarakhand Yudh Abhyas – 2019 India and United States Washington, US China, Tajikistan, India, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, "TSENTR 2019" Russia Pakistan and Uzbekistan Will conducted in "Hand in Hand" India and China december 2019 at Umroi, Meghalaya Warfare Exercise Andaman Island in the India "IndSpaceEx" Bay of Bengal Indian Army and French Mont de Marsan in Garuda-VI 2019 Army France Join Us On Telegram - https://t.me/examstocks LIST OF JOINT MILITARY EXERCISES OF INDIA 2019 Downloaded from www.examstocks.com Indian Army and Royal Jabel AI Akhdar training AL NAGAH III 2019 Oman Army camp, Oman Indo-Bangladesh SAMPRITI - 2019 Tangail, Bangladesh Military Exercise INDIA AFRICA FIELD Aundh Military Station India and Africa Military TRAINING EXERCISE and College of Military Exercise (IAFTX)- 2019 Engineering, Pune Babina Military Station India and Singapore Bold Kurukshetra 2019 in Jhansi -

Managing China: Competitive Engagement, with Indian Characteristics Tanvi Madan

MANAGING CHINA: COMPETITIVE ENGAGEMENT, WITH INDIAN CHARACTERISTICS TANVI MADAN FEBRUARY 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY major powers — including Australia, France, Japan, Russia, and the United States — that can help balance This paper explores India’s ties with China, outlining China, and build India’s and the region’s capabilities. how they have evolved over the course of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s years in office. It lays out the In this context, India has largely approved of the Trump elements of cooperation, competition, and potentially administration’s more competitive view of China, even conflict in the Sino-Indian relationship, as well as the as it does not have similar concerns about China as an leverage the two countries potentially hold over each ideological challenge and despite Delhi’s discomfort other. The paper also examines the approach that with certain elements of Washington’s approach Delhi has developed to manage its China relationship toward Beijing. Their broad strategic convergence on — one that can be characterized as “competitive China has laid the basis for U.S.-India cooperation engagement with Indian characteristics.” The paper across a range of sectors, particularly in the diplomatic, details how and why India is simultaneously engaging defense, and security spheres, as well as incentivized with Beijing, where that is feasible, and competing the two sides to manage or downplay their differences. with China, alone and in partnership with others. Finally, the paper considers what could cause India to This convergence could unravel if there is a major reevaluate its approach to China either toward greater Indian reorientation on China, but the paper argues accommodation or greater competition. -

Banking Current Affairs - 8-Nov-19 TABLE of CONTENTS A

BrainBuzz Academy Banking Current Affairs - 8-Nov-19 TABLE OF CONTENTS A.. IInternatiionall Rellatiions 1.. Fiirst ever IIndiia--U..S.. trii--serviices exerciise from November 13 B.. Economy 1.. PM Modii iinaugurates two--day Glloball iinvestors’’ meet iin Dharamshalla Internatiionall Rellatiions First ever India-U.S. tri-services exercise from November 13 ��Indian and American defence forces will hold their first tri-services amphibious exercise off the Andhra coast from November 13 to 21. ��US Marine Corps and a Special Forces reconnaissance team, Indian Navy’s P8i long-range maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare aircraft, among others, will participate in the exercise called Tiger Triumph. ��The ‘harbour phase’ will be in Visakhapatnam from November 13 to 16 and the second phase in Kakinada from November 17 to 21. ��Around 400 troops, including Army’s signal, medical and communication arms will participate in the exercise. ��Tiger TRIUMPH will include events and field training that simulate moving a humanitarian assistance and disaster relief force from ship to shore, a press release from the US. ��The exercise helps build the capacity of both the Indian and US participants, while improving their ability to operate together. ��About 1,200 Indian soldiers, sailors and airmen and 500 US marines, sailors and airmen will participate in the nine-day exercise. ��Tiger TRIUMPH gives US and Indian forces the opportunity to exchange knowledge and learn from each other as well as establish personal and professional relationships. ��During the exercise, the two forces will get familiar with one anothers aviation support capabilities. ��The Indian Air Force will conduct a cross-deck landing on the USS Germantowns flight deck and execute a simulated casualty evacuation from the shore to the acting hospital ship. -

Joint Military Exercise of India 2020

JOINT MILITARY EXERCISE OF INDIA 2020 NAME OF PARTICIPATING CONDUCTED EXERCISE NATIONS AT Dep Expo 2020 -- Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh AJEYA WARRIOR India and the United The United Kingdom 2020 Kingdom ‘Sahyog-Kaijin India and japan Chennai EX Indradhanush- V Indian Air Force (IAF) Air Force Station 2020 and Royal Air Force Hindon, Ghaziabad, Uttar (RAF) Pradesh BIMATEC disaster India Bangladesh, Nepal, Puri (Odisha) management exercise- Sri Lanka & Myanmar 2020 SAMPRITI-IX India and Bangladesh UMROI, Meghalaya India MILAN 2020 -- Visakhapatnam WWW.NAUKRIASPIANT.COM BY NAUKRI ASPIRANT JOINT MILITARY EXERCISES OF INDIA 2019 NAME OF PARTICIPATING CONDUCTED EXERCISE NATIONS AT ‘Exercise-SINDU Indian Army Pokharan, Rajasthan SUDARSHAN-VII’ SITMEX 2019 India, and Thailand Meghalaya Disaster Control Exercise India and Japan Yokohama in Japan SIMBEX 2019 Naval India, Singapore Naval The South China Sea Exercise Exercise AL NAGAH III 2019 Indian Army and Royal Jabel Al Akhdar training Oman Army Camp, Oman AUSINDEX 2019 India and Australia Vishakhapatnam SAMPRITI – 2019 Indo-Bangladesh Military Tangail, Bangladesh Exercise KAZIND-2019 India and Kazakhstan Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand Nomadic Elephant-XIV India and Mongolia Bakloh Hand-In-Hand-2019 VII India and China Umroi, Meghalaya NAVARMS-19 -- NEW Delhi WWW.NAUKRIASPIANT.COM BY NAUKRI ASPIRANT Mitra Shakti VI India- Sri Lanka Sri Lanka “TSENTER 2019” China, Tajikistan, India, Russia Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan and Uzbekistan Ekuverin 2019 India and Maldives Pune, Maharashtra MALABAR Exercise