Germaine Krull. Métal. 1928. Plates 36–39. All Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germaine Krull

Germaine Krull Germaine Krull est née le 29 y règne en maître et les photographes Hugo Erfurth et novembre 1897 de parents alle- Heinrich Kühn y sont cités en exemples. Elle est dans la mands à Poznan, une ville polo- classe du professeur Spörl pour qui la personne représen- naise qui fait partie du royaume tée n’est qu’un moyen pour atteindre un but : la représen- de Prusse depuis le Congrès de tation artistique. Elle adore l’école qui est une expérience Vienne, au hasard d’un déplace- absolument nouvelle, les travaux pratiques, son profes- ment professionnel de son père, seur, la découverte de la ville avec pour la première fois un ingénieur qui va ensuite des amies de son âge. rejoindre son poste en Bosnie où elle passera une partie de sa Elle fréquente la bohème munichoise et s’engage en Autoportrait, Paris, 1927 petite enfance. La famille s’ins- politique. Elle a son premier contact avec le bouddhisme talle ensuite dans la campagne romaine puis à Paris où « ... cette philosophie [qui] est la mienne depuis. La réin- sa mère tient une table d’hôtes « ... assez élégante. Il y a carnation ; les fautes que vous faites, vous les expiez ; la des attachés de consulats et quelques hommes de lettres, conscience de la vie qui tourne et qui revient2... ». C’est là des étudiantes en musique1. » Son père refuse qu’elle aille à qu’elle découvre l’art moderne, qu’elle forme son goût sous l’école et engage une préceptrice. Ensuite ce sera la Slové- l’infl uence d’un ami peintre plus âgé qu’elle. -

The Age of Distraction: Photography and Film Quentin Bajac

The Age of Distraction: Photography and Film quentin bajac Cult of Distraction In the immediate post–World War I period, distraction was perceived as one of the fundamental elements of the modern condition.1 These years — described as folles in French, roaring in the United States, and wilden in German2 — were also “distracted” years, in every sense of the term: in the sense of modern man’s new incapacity to focus his attention on the world, as well as a thirst to forget his own condition, to be entertained. In the eyes of then- contemporary observers, the new cinema — with its constant flux of images and then sounds, which seemed in contrast with the old contemplation of the unique and motionless work — offered the best illustration of this in the world of the visual arts (fig. 1). In 1926, in his essay “Kult der Zerstreuung” (Cult of distraction), Siegfried Kracauer made luxurious Berlin movie theaters — sites par excellence of the distraction of the masses — the point of departure and instrument of analysis of German society in the 1920s. In the temples of distraction, he wrote, “the stimulations of the senses suc- ceed each other with such rapidity that there is no room left for even the slightest contemplation to squeeze in between them,”3 a situation he compared to the “increasing amount of illustrations in the daily press and in periodical publications.”4 The following year, in 1927, he would pursue this idea in his article on photography,5 deploring the “bliz- zard” of images in the illustrated press that had come to distract the masses and divert the perception of real facts. -

Abattoirs De La Villette (1929) : Le Point De Vue Du Photographe Eli Lotar Par-Delà La Revue Documents Et La Philosophie De Georges Bataille

1 Université de Montréal La série Aux Abattoirs de la Villette (1929) : Le point de vue du photographe Eli Lotar par-delà la revue Documents et la philosophie de Georges Bataille Par Émilie Lesage Histoire de l’art et études cinématographiques Arts et sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise en Histoire de l’art Septembre 2009 © Émilie Lesage, 2009 2 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures Ce mémoire intitulé : La série Aux Abattoirs de la Villette (1929) : Le point de vue du photographe Eli Lotar par-delà la revue Documents et de la philosophie de Georges Bataille présenté par Émilie Lesage a été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : ……………...…Suzanne Paquet………………… président-rapporteur ………… …..Johanne Lamoureux……………… directrice de recherche ……………….…Serge Cardinal………………… membre du jury iii RÉSUMÉ Ce mémoire étudie la série Aux Abattoirs de la Villette photographiée par Eli Lotar en 1929. Il montre comment elle a été assimilée par l’histoire de l’art au texte « Abattoir » de Georges Bataille, aux côtés duquel ont été reproduites trois photos du corpus sous la rubrique Dictionnaire critique de la revue Documents . Cette emprise théorique sur la série est mise en perspective au regard de la démarche artistique d’Eli Lotar et des autres photomontages dont elle a fait l’objet ensuite. Le premier chapitre insiste sur la formation d’Eli Lotar et introduit son séjour à La Villette en lien avec la thématique de l’abattoir dans l’entre-deux-guerres. Il analyse ensuite la fortune critique d’ Aux Abattoirs de la Villette qui s’appuie sur la philosophie de l’informe chez Georges Bataille. -

La Visió Del Col·Leccionista. Els Millors Fotollibres Segons Martin Parr

1 - La visió del col·leccionista. Els millors fotollibres segons Martin Parr Owen Simmons (fotògraf desconegut) The Book of Bread Maclaren and Sons, Londres, 1903 Vladimir Maiakovski i Aleksandr Ródtxenko Pro eto. Ei i mne Gos. Izd-vo (publicacions de l’Estat), Moscou, 1923 Albert Renger-Patzsch Die Welt ist Schön Kurt Wolff Verlag, Munic, 1928 Germaine Krull Métal Librairie des Arts Décoratifs, París, 1928 August Sander Antlitz der Zeit: 60 Fotos Deutscher Menschen Transmare Verlag i Kurt Wolff Verlag, Munic, 1929 Bill Brandt The English at Home B. T. Batsford Ltd., Londres, 1936 Comissariat de propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya Madrid Indústries Gràfiques Seix i Barral, Barcelona, 1937 Robert Capa Death in the Making Covici Friede Inc., Nova York, 1938 Heinrich Hoffmann (ed.) Winterhilfswerk-Heftchen Bild-Dokumente Heinrich Hoffmann, Munic, de 1938 a c. 1942 KZ: Bildbericht aus fünf Konzentrationslagern Oficina d’informació de guerra nord-americana), 1945 imoni col·locat ho gaudeix] Éditions du Seuil, Album Petite Planete, París, 1956 The Great Hall of the People Editorial de belles arts del poble, Pequín, 1959 Dirk Alvermann Algerien / L’Algérie Rütten & Loening, Berlín, 1960 Dirk Alvermann vitrina Parr Algerien / L’Algérie Rütten & Loening, Berlín, 1960 (facsímil 2011) Kazuo Kenmochi Narcotic Photographic Document Inoue Shoten, Tòquio, 1963 Kazuo Kitai Teikoh Mirai-sha Press, Tòquio, 1965 Ed van der Elsken Sweet Life Harry N. Abrams Inc., Nova York, 1966 Gian Butturini London Editrice SAF, Verona, 1969 Enrique Bostelmann América: -

Dossier De Presse Germaine Krull 2001

Centre Pompidou Germaine Krull 17 novembre 2000 - 5 février 2001, Galerie 3, niveau 6 Dans le cadre du Mois de la photo à Paris, novembre 2000 Le Centre Pompidou présente, dans le cadre du Mois de la photo à paris, une exposition consacrée à la photographe Germaine Krull (1897-1985), auteur de Métal, véritable manifeste de la " modernité photographique ". Cette manifestation, conçue par le Museum Folkwang d'Essen, est la première rétrospective d'importance de l'oeuvre de Germaine Krull depuis l'exposition que lui consacra le musée Reattu à Arles en 1988 . Elle réunit une centaine d'oeuvres de l'artiste provenant des archives conservées par le Museum Folkwang, mais également des collections du Musée national d'art moderne au Centre Pompidou et d'importantes collections privées. Commissariat de l'exposition : Alain Sayag, conservateur de la photographie au Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Pompidou et Ute Eskildsen, directeur du département photographie au Museum Folkwang d'Essen Catalogues disponibles: Avantgarde als abenteuer : Leben und werk der Photographin Germaine Krull Kim Sichel, Museum Folkwang, Essen SchirmerMosel, München, 1999 Germaine Krull, Photographer of Modernity Kim Sichel, Museum Folkwang, Essen The M .I.T. Press Cambridge, Massachussetts, 1999 Informations pratiques : Exposition ouverte au public du 17 novembre 2000 au 5 février 2001, tous les jours sauf le mardi. horaires : de l lh à 21h tarif : 40F / tarif réduit : 30F pour plus d'informations : www .centre pompidou.fr Contact presse : Direction de la communication du Centre Pompidou Anne de Nesle tél. 01 44 78 46 50 / fax 01 44 78 13 40 / mél : anne.deneslegcnac-gp.fr Germaine Krull Née en1897 de parents allemands, dans une région devenue polonaise en 1921 à la suite du traité de Versailles, Germaine Krull passe son enfance dans diverses villes d'Europe avant que sa famille ne s'installe à Munich en 1912 . -

Curriculum Vitae

Boston University College of Arts & Sciences Department of History of Art & Architecture KIM D. SICHEL Department of History of Art & Architecture Boston University 725 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 302, Boston MA 02215 (781)-640-3881, [email protected], bu.edu/ah EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986, M.Phil. 1983, M.A. 1981, Yale University (History of Art) Dissertation: “Photographs of Paris 1928-1934: Brassaï, André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Man Ray” A.B. 1977, Brown University (double major History and History of Art) EMPLOYMENT Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture Associate Professor, History of Art & Architecture, 2000-present Chair, Department of History of Art & Architecture, 2002-2005 Director, Museum Studies, 1990-1992, 1998-1999 Assistant Professor, History of Art & Architecture, 1987-2000 Associate Professor, American & New England Studies Program, 2013-present Director, Undergraduate Studies, AMNESP, 2019-2021 Director, American and New England Studies Program, 2009- 2012 Director, Graduate Studies, American & New England Studies, 2010-11, 2014-15 Director, Boston University Art Gallery 1992-1998 Smith College Visiting Assistant Professor, History of Art, 1986-1987 Yale University Lecturer, Yale University, History of Art, 1985-86 Teaching Fellow, History of Art, 1981-1983 GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS Millard Meiss Publication Fund Award, College Art Association, 2019 (Making Strange) Jeffrey Henderson Senior Research Fellowship, Boston University Center for the Humanities, 2015-16 (Making Strange) Boston University Center for the Humanities Publication Subvention, 2018 (Making Strange) Humanities Research Fund Grant, College of Arts & Sciences, Boston University, 2019, 2020 Senior Research Fellow, Boston University Humanities Foundation, 2005-2006 Finalist, Kraszna-Krausz Foundation Book Award, London, 2000 (Germaine Krull) Golden Light Award, Best Photographic Book 1999, Maine Photographic Workshops (Germaine Krull) Florence J. -

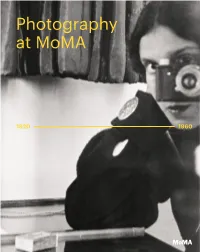

Read a Free Sample

Photography at MoMA Contributors Quentin Bajac is The Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Museum of Modern Art draws upon the exceptional depth of its collection to tell a new history of photography in the three-volume series Photography at MoMA. Douglas Coupland is a Vancouver-based artist, writer, and cultural critic. The works in Photography at MoMA: 1920–1960 chart the explosive development Lucy Gallun is Assistant Curator in the Department of the medium during the height of the modernist period, as photography evolved of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, from a tool of documentation and identification into one of tremendous variety. New York. The result was nothing less than a transformed rapport with the visible world: Roxana Marcoci is Senior Curator in the Department Walker Evans's documentary style and Dora Maar's Surrealist exercises in chance; of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, El Lissitzky's photomontages and August Sander's unflinching objectivity; New York. the iconic news images published in the New York Times and Man Ray's darkroom experiments; Tina Modotti's socioartistic approach and anonymous snapshots Sarah Hermanson Meister is Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum taken by amateur photographers all over the world. In eight chapters arranged of Modern Art, New York. by theme, this book presents more than two hundred artists, including Berenice Abbott, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Geraldo de Barros, Margaret Bourke-White, Kevin Moore is an independent curator, writer, Bill Brandt, Claude Cahun, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, and advisor in New York. -

<I>Arts Et Métiers</I> PHOTO-<I>Graphiques</I>

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Arts et Métiers PHOTO-Graphiques: The Quest for Identity in French Photography between the Two World Wars Yusuke Isotani The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3463 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ARTS ET MÉTIERS PHOTO-GRAPHIQUES: THE QUEST FOR IDENTITY IN FRENCH PHOTOGRAPHY BETWEEN THE TWO WORLD WARS by YUSUKE ISOTANI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 ii © 2019 YUSUKE ISOTANI All Rights Reserved iii Arts et Métiers PHOTO-Graphiques: The Quest for Identity in French Photography between the Two World Wars by Yusuke Isotani This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Romy Golan Chair of Examining Committee Date Rachel Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Maria Antonella Pelizzari Siona Wilson Christian Joschke THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Arts et Métiers PHOTO-graphiques: The Quest for Identity in French Photography between the Two World Wars by Yusuke Isotani Advisers: Professors Romy Golan and Maria Antonella Pelizzari This dissertation examines the evolution of photography in France between the two World Wars by analyzing the seminal graphic art magazine Arts et métiers graphiques (1927- 1939). -

PDF Catalogue

2021 TH 6 1 pril A , ienna V 1 23. OSTLICHT PHOTO AUCTION 23RD OSTLICHTPHOTO AUCTION Freitag, 16. April 2021, 17 Uhr (MESZ) Friday, April 16TH 2021, 5 pm (CEST) VORBESICHTIGUNG/VIEWING ab Dienstag, 6. April nach persönlicher Vereinbarung: [email protected] from Tuesday, April 6th only by appointment: [email protected] Tel.: +43 1 996 20 66 17 UPDATED BUYER’S PREMIUM The total purchase price for all lots consists of the hammer price plus the premium of 26 % (incl. the reduced VAT of 5 % only) for lots remaining in the EU. For lots that are exported to third countries or purchased with a valid VAT number the premium is 20 %. For general enquiries about this auction, email LOT 149 should be addressed to [email protected] 2 FEATURED LOTS 1 HEINRICH KÜHN (1866 – 1944) ‘Nude Study’, Tyrol 1907 Gum pigment print, Vintage 30,4 × 24,7 cm (12 × 9.7 in) Registration marks by the photographer on the reverse LITERATURE Heinrich Kühn (1866 – 1944), Innsbruck 1978, p. 77; Heinrich Kühn, Die vollkommene Fotografie, Albertina Vienna 2010, p. 134. (Nude study Mary Warner). € 18.000 / € 30.000 – 40.000 Die 1907 entstandene Aktstudie zeigt Heinrich Kühns Muse Mary Warner. Die Wiedergabe der zarten Lichtreflexe im langen Haar, sowie der sorgfältig gesetzte Kontrast zwischen der hell schimmernden Haut und dem dunklen Hintergrund bezeugen Kühns künstlerische Meister- schaft. Mary Warner, welche Kühn selbst als das „geduldigste Modell“ bezeichnete, arbeitete ab 1904 als Kindermädchen für die Kühns und posierte oft stundenlang für die minutiös vorbereiteten Arran- gements, die alle darauf zielten „die delikatesten Feinheiten des Lichtspiels mit fast unübertrefflicher Vornehmheit und überzeugender Wahrheit zu schildern“, wie Kühn es beschrieb. -

Catalogue Photo 2006

PHOTOGRAPHIE DENIS OZANNE CHLOE & DENIS OZANNE 18 RUE DE PROVENCE 75009 PARIS (SUR RENDEZ-VOUS) 33 (0)1 48 01 02 37 33 (0)1 48 01 06 29 [email protected] MAQUETTE (ILLUSIONS) • PHOTO DE COUVERTURE SERGE BILOUS • REPRODUCTIONS FRANCOIS DOURY 1. 50 JAHRE MADAUS: EINE AUFGESCHLOSSENE FIRMA Cologne, Dr Madaus & Co, sans date (1969), 295x237mm, 70p.+couverture, dos toilé, étui à décor photographique. L'illustration, entièrement réalisée à partir des photographies de Barbara Schulter, comprend en outre : • une grande double page dépliante et une page double avec un petit accordéon • 11 objets hors texte dont deux double pages faisant apparaître des scènes en relief • un fac-similé d'affiche, un fac-similé d'une 2. ANSEL ADAMS (1902-1984) brochure ancienne de la firme, une carte postale. Yosemite and the Range of Light Conception graphique de Peter Selinka, Boston, New York Graphic Society, 1979, 312x392mm, texte de Siegfried Leuselhardt. 144p., pleine toile rouge et grise de l'éditeur, jaquette Remarquable plagiat du Warhol Index publié photographique. à New York deux ans plus tôt, pour cette firme Illustré de 116 photographies reproduites pleine page de produits pharmaceutiques. en lithographie offset, texte d'introduction de Paul Quelques défauts à la reliure. Brooks, index. Parr & Badger II 196-197. Edition originale et premier tirage, très bel état, prix sur le premier rabat de la jaquette ($75) non coupé. La Yosemite Valley occupe une place centrale dans l'oeuvre et la vie d'Ansel Adams, qui la photographia pour la première fois à l'age de 14 ans avec son Box Brownie et y établit sa vie; la beauté glaciale des paysages, déjà maintes fois louée par ses premiers découvreurs à partir du milieu du XIXe siècle lui inspira des milliers d'images. -

Images of a Capital the Impressionists in Paris Museum Folkwang Images of a Capital the Impressionists in Paris Museum Folkwang

Images of a Capital The Impressionists in Paris Museum Folkwang Images of a Capital The Impressionists in Paris Museum Folkwang Curator: Françoise Cachin, with Monique Nonne Curators of Photography: Françoise Reynaud and Virginie Chardin Project Manager: Sandra Gianfreda The exhibition is under the patronage of Federal Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany Angela Merkel and the President of the French Republic Nicolas Sarkozy. Contents The Modern City: Paris 1850–1900 | Caroline Mathieu 5 Paris – Capital of the Civilized World? | Robert Kopp 12 The Impressionist Cityscape as an Emblem of Modernity | James H. Rubin 20 The City Reflected in the New Picture Ground: Manet | Bruno Haas 29 Paris and Photography between 1839 and 1900 | Virginie Chardin 39 A Journey through the Photographic Collections of Paris | Françoise Reynaud 47 Traffic – The City and its Flowing Elements | Michel Frizot 54 Emile Zola and Paris of the Impressionists | Karlheinz Stierle 61 Paris as Seen by the Painters | Monique Nonne 67 Paris Aglow | Françoise Cachin 76 Short Biographies of the Authors 78 Imprint 79 Editor’s comment: Information given in square brackets pertains to the numbers and page references of the images printed in the German edition of the exhibition catalogue Bilder einer Metropole – Die Impressionisten in Paris, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Göttingen: Edition Folkwang/Steidl, 2010. The Modern City: Paris 1850–1900 Caroline Mathieu “Paris has been destroyed,”1 “Paris disappears and returns,”2 “Paris shines in new splendor,”3 “the new Paris and the Paris of the future”4 – the city has a firm place in publications, be it books or illustrated magazines. -

Germaine Krull Un Destin De Photographe a Photographer’S Journey 02/06 – 27/09/2015

GERMAINE KRULL UN DESTIN DE PHOTOGRAPHE A PHOTOGRAPHER’S JOURNEY 02/06 – 27/09/2015 [ F R / EN ] GERMAINE KRULL (1897-1985) Certaines inclinations caractérisent cette femme UN DESTIN DE PHOTOGRAPHE d’action et d’initiative : l’engouement pour l’automobile et pour le voyage par la route Figure célèbre de l’avant-garde des années (qui donne lieu à des livres) ; l’attention aux 1920-1940, Germaine Krull (Wilda, Pologne, comportements, aux gestes, aux travaux féminins ; 1897-Wetzlar, Allemagne, 1985) est une pionnière la fascination pour les mains ; enfin l’esprit libre du reportage photographique moderne et de la et fantasque auquel elle cède à toute occasion, publication de livres photographiques. Son œuvre comme si l’approche renouvelée du monde relevait novatrice, située essentiellement entre 1928 et 1931, constamment d’un défi photographique. « Germaine ne peut se comprendre sans la prise en compte d’une Krull, note Pierre Mac Orlan, ne crée pas des enfance chaotique, à l’éducation déficiente, et d’une anecdotes faciles, mais elle met en évidence le détail jeunesse activiste, mêlée aux aléas de la révolution secret que les gens n’aperçoivent pas toujours. » spartakiste dans l’Allemagne de 1919. Après Berlin, où elle élabore en 1923 des nus Berlin et Paris, les débuts féminins ambigus, c’est à Paris que se réalise son Après une adolescence aux mœurs très libres, destin de photographe, par la reconnaissance de Germaine Krull étudie la photographie à Munich et ses « fers », architectures métalliques, ponts et grues participe à l’édition d’un portfolio de nus féminins. qui forment le portfolio Métal (1928), représentatif Son engagement dans la révolution spartakiste en de la Nouvelle Vision photographique et de ses 1919 l’amène jusque dans les geôles de Moscou angles de vue inusités.