Effective Pre-School, Primary and Secondary Education 3-14 Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Adult and Continuing Education

History of Adult and Continuing Education The Adult and Continuing Education function has been central to the mission of the college since its founding in 1966. Originally it was one of three major college focal points along with vocational-technical education and student services. The department’s mission is consistent with several of the directives in SF550, the law that created the community college system in Iowa in 1966: Programs for in-service training and retraining of workers; Developmental education for persons academically or personally underprepared to succeed in their program of study; Programs for training, retraining, and preparation for productive employment of all citizens; and Programs for high school completion for students of post-high school age. The 1968 North Central Association Self Study prepared constructive notes as a first step toward regional accreditation on these major functions of the department: Adult and Continuing Education provided educational programs in four areas: adult basic education, adult high school diploma programs, high school equivalency programs, and general adult education. Adult basic education programs developed throughout the area provided instruction to adults with less than an eighth grade education. Adult high school diploma programs provided instruction to adults with a 10th grade education but less than a high school education. Students enrolled in these programs were working toward the completion of a high school program and the receipt of a diploma from an established secondary school within the area. High school equivalency programs provided instruction to students who had completed at least eighth grade, and by completing additional course work, could be granted a high school equivalency certificate by the Iowa State Department of Public Instruction. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

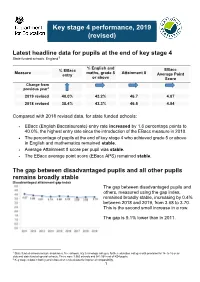

Key Stage 4 Performance, 2019 (Revised)

Key stage 4 performance, 2019 (revised) Latest headline data for pupils at the end of key stage 4 State funded schools, England1 % English and % EBacc EBacc Measure maths, grade 5 Attainment 8 entry Average Point or above Score Change from 2 previous year 2019 revised 40.0% 43.2% 46.7 4.07 2018 revised 38.4% 43.3% 46.5 4.04 Compared with 2018 revised data, for state funded schools: • EBacc (English Baccalaureate) entry rate increased by 1.6 percentage points to 40.0%, the highest entry rate since the introduction of the EBacc measure in 2010. • The percentage of pupils at the end of key stage 4 who achieved grade 5 or above in English and mathematics remained stable. • Average Attainment 8 score per pupil was stable. • The EBacc average point score (EBacc APS) remained stable. The gap between disadvantaged pupils and all other pupils remains broadly stable Disadvantaged attainment gap index The gap between disadvantaged pupils and others, measured using the gap index, remained broadly stable, increasing by 0.4% between 2018 and 2019, from 3.68 to 3.70. This is the second small increase in a row. The gap is 9.1% lower than in 2011. 1 State funded schools include academies, free schools, city technology colleges, further education colleges with provision for 14- to 16-year- olds and state-funded special schools. There were 3,965 schools and 542,568 end of KS4 pupils. 2 Key stage 4 data in both years is based on revised data for improved comparability. 1 About this release This release summarises exam entry and achievements of pupils at the end of key stage 43 (KS4) in 2019. -

(PDF) Understanding the Foundation Stage

Contents Introduction 1 The Rationale of the Foundation Stage • The Characteristics of the Foundation Stage 2 • The Aims of the Foundation Stage 3 • The Principles Underpinning the Foundation Stage 4 • The Curriculum in the Foundation Stage 5 Creating an Effective Learning Environment • The Approach to Learning and Teaching in the Foundation Stage 6 • Adults’ Role in Promoting Learning 7 • Learning Partnerships 7 • The Physical Environment 8 Learning, Teaching and Assessment • The Learning, Teaching and Assessment Cycle in the Foundation Stage 9 • Planning in the Foundation Stage 11 • Assessment for Learning in the Foundation Stage 13 • Observation and Assessment in the Foundation Stage 13 • The Pupil Profile in the Foundation Stage 15 Acknowledgements This material has been developed in collaboration with the Early Years Interboard Group. Understanding the Foundation Stage Introduction The Foundation Stage Years 1 & 2 in the primary school The purpose of this guidance is to provide information related to good practice in the Foundation Stage. It outlines the approach to learning, teaching and assessment and should be used to support the review, development and improvement of existing provision and practice. Young children come to school from a variety of different backgrounds, having had a range of diverse learning experiences at home and for most, some form of pre-school education. The Foundation Stage aims to build on these learning experiences by providing children with an appropriate learning programme to develop their dispositions to learn and to provide them with the skills and competencies they will need to succeed in school and future life. The Foundation Stage also endorses good early years practice where teachers have more flexibility in terms of what they teach. -

RE: Statutory Requirements, Compliance and OFSTED

RE: Statutory requirements, compliance and OFSTED Statutory requirements and curriculum information The national curriculum states the legal requirement that: 'Every state-funded school must offer a curriculum which is balanced and broadly based, and which: • promotes the spiritual, moral, cultural, mental and physical development of pupils; and • prepares pupils at the school for the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of later life. All state schools ... must teach religious education ... All schools must publish their curriculum by subject and academic year online'. (National Curriculum in England: Framework Document, DfE, September 2013, p.4) Although there is not a National Curriculum for RE, all maintained schools must follow the National Curriculum requirements to teach a broad and balanced curriculum, which includes RE. All maintained schools therefore have a statutory duty to teach RE. Academies and free schools are contractually required through the terms of their funding agreement to make provision for the teaching of RE. Further information concerning RE in academies and free schools is given below. The RE curriculum is determined by the local Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education (SACRE), which is responsible for producing the locally agreed syllabus for RE. Agreed Syllabuses used in schools (maintained or academy), which are not designated with a religious character must ‘reflect the fact that the religious traditions in Great Britain are in the main Christian, while taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in Great Britain’. Schools with a religious designation may prioritise one religion in their RE curriculum, but all schools must recognise diverse religions and systems of belief in the UK both locally and nationally. -

Secondary School Course Classification System: School Codes for the Exchange of Data (SCED) (NCES 2007-341)

Secondary School Course Classification U.S. Department of Education NCES 2007-341 System: School Codes for the Exchange of Data (SCED) Secondary School Course Classification System: School U.S. Department of Education Codes for the NCES 2007-341 Exchange of Data (SCED) June 2007 Denise Bradby Rosio Pedroso MPR Associates, Inc. Andy Rogers Consultant Quality Information Partners Lee Hoffman Project Officer National Center for Education Statistics U.S. Department of Education Margaret Spellings Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Grover J. Whitehurst Director National Center for Education Statistics Mark Schneider Commissioner The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing, and reporting data related to education in the United States and other nations. It fulfills a congressional mandate to collect, collate, analyze, and report full and complete statistics on the condition of education in the United States; conduct and publish reports and specialized analyses of the meaning and significance of such statistics; assist state and local education agencies in improving their statistical systems; and review and report on education activities in foreign countries. NCES activities are designed to address high-priority education data needs; provide consistent, reliable, complete, and accurate indicators of education status and trends; and report timely, useful, and high-quality data to the U.S. Department of Education, the Congress, the states, other education policymakers, practitioners, data users, and the general public. Unless specifically noted, all information contained herein is in the public domain. We strive to make our products available in a variety of formats and in language that is appropriate to a variety of audiences. -

An Evaulation of Key Stage 3 2007

An Evaluation of Key Stage 3 2007 S13/2007 November 2007 FAMILY AND CHILDREN’S SERVICES POLICY AND PERFORMANCE KEY STAGE 3, 2007 Research Report S13/2007 This research report presents an analysis of Key Stage 3 results in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in 2007. Results are compared with statistical neighbours and the national averages, and with previous years. Results are presented by school and are contextualised by gender, entitlement to receive a free school meal, SEN, ethnicity, time in school, term of birth, IDACI and pupils’ attendance. The Royal Borough’s results are compared with the 2007 national average and with previous years. The results of a ‘value-added’ assessment of pupil achievement at Key Stage 3 (2007) are presented, using pupils’ previous achievement at Key Stage 2 (2004) as the baseline measure. Further Sam Utting or Diana Hall information available from: Telephone: 0207 361 3096 or 0207 598 4815 Policy and Performance welcomes your comments on this and other reports, and any suggestions for future research. KEY STAGE 3 2007 CONTENTS Paragraph numbers: 1 Introduction 2 The requirements of Key Stage 3 Statutory Assessment in 2007. 3 The structure of Key Stage 3 Assessment in 2007. 4 Evaluation of Key Stage 3 Targets in 2007. 5 Summary of results 6 Borough level results 7 Holland Park 8 St Thomas More 9 Sion Manning 10 Cardinal Vaughan 11 Factors affecting performance (borough level) 12 Ethnicity 13 Attendance 14 Key Stage 2 (2004) to Key Stage 3 (2007) 15 Looked After Children 16 Conclusion 17 Recommendations -

The Sciences at Key Stage 4: Time for a Re-Think? Why Key Stage 4 Is So Important, and Why Changes Are Needed

The sciences at key stage 4: time for a re-think? Why key stage 4 is so important, and why changes are needed Key stage 4 is a pivotal period of time in a student’s chemistry and biology are currently the preserve of school life; it is the point at which they make subject a minority. There is evidence that the existence of choices that define their future study, as well as their multiple routes through key stage 4 disadvantages a last experience of those subjects that they do not large number of students in both their experiences and choose to take further. The sciences are core subjects the choices that are taken away from them. For this to 16, yet multiple qualifications exist for students reason, the SCORE organisations are proposing that of this age. As this discussion paper documents, there should be a single route in the sciences for all evidence suggests that rich opportunities in physics, students up to the age of 16. SCORE’sSCORE’s proposal: proposal: a asingle single route route in in the the sciences sciences SCORE’sSCORE’s vision vision is thatis that opportunities opportunities for forhigh-quality high-quality studyexciting of the sciences and inspiring are available experience to all, of onthe an sciences, studyequitable of the sciencesbasis, and are we available believe thatto all, this on can an only be achievedproviding by the them creation with ofthe a skillssingle and route knowledge at key to equitablestage 4. basis, This singleand we route believe would that remove this can the only need for decisionssucceed to be in madetheir future at 14 endeavours,that could limit whether students’ or not be futureachieved choices, by the and creation give all of students a single routean authentic, at key excitingthey and decideinspiring to experience pursue the ofsciences the sciences, beyond 16. -

Terms for School Levels This Table Features Education Terms Used in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and Other Countries

Terms for School Levels This table features education terms used in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and other countries. This includes reference to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) maintained by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This table provides a general sense of school terminology and age ranges, as there are differences within each country or sovereign country. In those respects, Quebec differs slightly from British Columbia, Scotland differs slightly from England, etc. This table is one of the eResources from the book Sharing Your Education Expertise with the World: Make Research Resonate and Widen Your Impact by Jenny Grant Rankin, Ph.D. See the book for terminology explanations and more. Age Canadian Terms US Terms UK Terms UNESCO ISCED Terms early junior kindergarten, early preschool, nursery school Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)ante-pre-school, early childhood early childhood ≤ 4 childhood pre-kinder., preschool education primary nursery childminders, education, educational education kindergarten, primary stage infant, key stage 1 children's Level 0 development, pre- 5 K-12 primary elementary school centre, nursery Level 1 primary education classes/school, elementary grades 1-8 (in (kindergarten school (starts with grade TK or 6 pre-school, education Quebec, grade through K and ends after 6th primary school, school and the first grade 12) or grade around age 11 if or reception 7 half of high school) TK-12 student goes on to (transitional middle school; -

Social Selectivity of State Schools and the Impact of Grammars

_____________________________________________________________________________ Social selectivity of state schools and the impact of grammars A summary and discussion of findings from ‘Evidence on the effects of selective educational systems’ by the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University The Sutton Trust, October 2008 Contents Executive summary 3 Introduction and background 5 Findings -- selectivity 7 Findings – pupil intakes 10 Findings – attainment 12 Discussion 13 Proposed ways forward 16 Appendix 18 2 Executive summary Overview This study shows that the vast majority of England's most socially selective state secondary schools are non-grammar schools. However, England's remaining grammar schools are enrolling half as many academically able children from disadvantaged backgrounds as they could do. The research also concludes that the impact on the academic results of non-grammar state schools due to the ‘creaming off’ of pupils to grammar schools is negligible. Grammars have a widespread, low-level, impact on pupil enrolments across the sector. A relatively small number of non-selective schools do see a significant proportion of pupils ‘lost’ to nearby grammars, but this does not lead to lower academic achievement. The Trust proposes that a further study be undertaken to review ‘eleven plus’ selection tests to see whether they deter bright pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds applying to grammar schools, and urges more grammars to develop outreach schemes to raise the aspirations and achievement of children during primary school. It also backs calls for religious schools to consider straightforward 'binary' criteria to decide which pupils should be admitted on faith grounds, and other ways – including the use of banding and ballots – to help make admissions to all secondary state schools operate more equitably. -

Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project

Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project August 2005 Prepared by Keith Fuller (Senior Consultant) Frank Thomas (Associate Consultant) Colin Horswell Mouchel Parkman Strelley Hall Nottingham NG8 6PE T +44 (0)115 9061 313 F +44 (0)115 9061 302 Prepared for KS2-3 Transition Design Collaborative Steering Group Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the staff and pupils of the following for their co-operation and support in the compilation of this report. Seven Kings High School (Redbridge); Valentines High School (Redbridge); Archbishop Tenison’s C of E High School (Croydon); Norbury Manor High School for Girls (Croydon); Jo Richardson Community School (Barking and Dagenham); Haydon School (Hillingdon); Rutlish School (Merton); Preston Manor High School (Brent); Battersea Technology College (Wandsworth); Lady Margaret School (Hammersmith and Fulham); Stockwell Park School (Lambeth); Highbury Fields School (Islington); Stanley Park High School (Sutton); Park View Academy (Haringey); Tolworth Girls’ School (Kingston-upon-Thames); The Ravensbourne School (Bromley); Little Ilford School (Newham). Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 Transition Project Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................1 2 Methodology ...............................................................................................3 2.1 The questionnaire and interviews in schools.................................................3 2.2 Good practice -

Opening a Studio School a Guide for Studio School Proposer Groups on the Pre-Opening Stage

Opening a studio school A guide for studio school proposer groups on the pre-opening stage August 2014 Contents Introduction 3 Section 1 - Who does what - roles and responsibilities? 5 Section 2 - Managing your project 10 Section 3 – Governance 12 Section 4 - Pupil recruitment and admissions 21 Section 5 - Statutory consultation 33 Section 6 - Staffing and education plans 36 Section 7 - Site and buildings 42 Section 8 – Finance 56 Section 9 - Procurement and additional support 63 Section 10 - Funding Agreement 67 Section 11 - The equality duty 71 Section 12 - Preparing to open 73 Section 13 - Once your school is open 80 Annex A - RSC regions and Local authorities 82 2 Introduction Congratulations! All your planning and preparation has paid off, and the Secretary of State for Education has agreed that your application to open a studio school should move to the next stage of the process – known as the ‘pre-opening’ stage. This is the stage between the approval of your application and the opening of the school. The setting up of a studio school is a challenging but ultimately very rewarding task and it will require significant commitment and time from sponsors and partners. Your original application set out your plans for establishing the studio school, from the education vision and the admission of pupils to the recruitment of staff and the curriculum. Now your application has been approved, you must begin work to implement these plans. The letter of approval you received from the Department for Education (DfE) sets out important conditions of approval. It is vital that you consider these conditions carefully in planning your priorities and what you need to focus on next.