Money and Modernization in Early Modern England Nuno Palma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European and Chinese Coinage Before the Age of Steam*

《中國文化研究所學報》 Journal of Chinese Studies No. 55 - July 2012 The Great Money Divergence: European and Chinese Coinage before the Age of Steam* Niv Horesh University of Western Sydney 1. Introduction Economic historians have of late been preoccupied with mapping out and dating the “Great Divergence” between north-western Europe and China. However, relatively few studies have examined the path dependencies of either region insofar as the dynamics monetiza- tion, the spread of fiduciary currency or their implications for financial factor prices and domestic-market integration before the discovery of the New World. This article is de- signed to highlight the need for such a comprehensive scholarly undertaking by tracing the varying modes of coin production and circulation across Eurasia before steam-engines came on stream, and by examining what the implications of this currency divergence might be for our understanding of the early modern English and Chinese economies. “California School” historians often challenge the entrenched notion that European technological or economic superiority over China had become evident long before the * Emeritus Professor Mark Elvin in Oxfordshire, Professor Hans Ulrich Vogel at the University of Tübingen, Professor Michael Schiltz and Professor Akinobu Kuroda 黑田明伸 at Tokyo University have all graciously facilitated the research agenda in comparative monetary his- tory, which informs this study. The author also wishes to thank the five anonymous referees. Ms Dipin Ouyang 歐陽迪頻 and Ms Mayumi Shinozaki 篠崎まゆみ of the National Library of Australia, Ms Bick-har Yeung 楊 碧 霞 of the University of Melbourne, and Mr Darrell Dorrington of the Australian National University have all extended invaluable assistance in obtaining the materials which made my foray into this field of enquiry smoother. -

Control of the Value of Black Goldminers' Labour-Power in South

Farouk Stemmet Control of the Value of Black Goldminers’ Labour-Power in South Africa in the Early Industrial Period as a Consequence of the Disjuncture between the Rising Value of Gold and its ‘Fixed Price’ Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Glasgow October, 1993. © Farouk Stemmet, MCMXCIII ProQuest Number: 13818401 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818401 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVFRSIT7 LIBRARY Abstract The title of this thesis,Control of the Value of Black Goldminers' Labour- Power in South Africa in the Early Industrial Period as a Consequence of the Disjuncture between the Rising Value of Gold and'Fixed its Price', presents, in reverse, the sequence of arguments that make up this dissertation. The revolution which took place in the value of gold, the measure of value, in the second half of the nineteenth century, coincided with the need of international trade to hold fast the value-ratio at which the world's various paper currencies represented a definite weight of gold. -

Monetization of Fiscal Deficits and COVID-19: a Primer

The Journal of Financial Crises Volume 2 Issue 4 2020 Monetization of Fiscal Deficits and COVID-19: A Primer Aidan Lawson Financial Stability Institute, Bank for International Settlements Greg Feldberg Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal-of-financial-crises Part of the Economic Policy Commons, Finance Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Other Economics Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Aidan and Feldberg, Greg (2020) "Monetization of Fiscal Deficits and COVID-19: A Primer," The Journal of Financial Crises: Vol. 2 : Iss. 4, 1-35. Available at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal-of-financial-crises/vol2/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journal of Financial Crises and EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monetization of Fiscal Deficits and COVID-19: A Primer Aidan Lawson† Greg Feldberg‡ ABSTRACT Monetization—also known as “money-financed fiscal programs” or “money-printing”— occurs when a government finances itself by issuing currency or other non-interest-bearing liabilities, such as bank reserves. It poses real risks—potentially excessive inflation and encroachment on central-bank independence—and some paint it as a relic of a bygone era. The onset of the COVID-19 crisis, however, forced governments to spend heavily to combat the considerable economic and public health impacts. As government deficits climbed, monetization re-entered the conversation as a way to avoid the massive debt burdens that some nations may face. This paper describes how monetization works, provides key historical examples, and examines recent central-bank measures. -

1 ENTER the GHOST Cashless Payments in the Early Modern Low

ENTER THE GHOST Cashless payments in the Early Modern Low Countries, 1500-18001 Oscar Gelderbloma and Joost Jonkera, b Abstract We analyze the evolution of payments in the Low Countries during the period 1500-1800 to argue for the historical importance of money of account or ghost money. Aided by the adoption of new bookkeeping practices such as ledgers with current accounts, this convention spread throughout the entire area from the 14th century onwards. Ghost money eliminated most of the problems associated with paying cash by enabling people to settle transactions in a fictional currency accepted by everyone. As a result two functions of money, standard of value and means of settlement, penetrated easily, leaving the third one, store of wealth, to whatever gold and silver coins available. When merchants used ghost money to record credit granted to counterparts, they in effect created a form of money which in modern terms might count as M1. Since this happened on a very large scale, we should reconsider our notions about the volume of money in circulation during the Early Modern Era. 1 a Utrecht University, b University of Amsterdam. The research for this paper was made possible by generous fellowships at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies (NIAS) in Wassenaar. The Meertens Institute and Hester Dibbits kindly allowed us to use their probate inventory database, which Heidi Deneweth’s incomparable efforts reorganized so we could analyze the data. We thank participants at seminars in Utrecht and at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, and at the Silver in World History conference, VU Amsterdam, December 2014, for their valuable suggestions. -

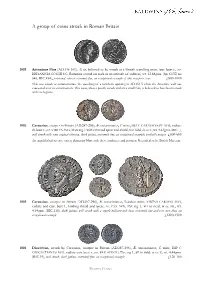

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

Is Monetary Financing Inflationary? a Case Study of the Canadian Economy, 1935–75

Working Paper No. 848 Is Monetary Financing Inflationary? A Case Study of the Canadian Economy, 1935–75 by Josh Ryan-Collins* Associate Director Economy and Finance Program The New Economics Foundation October 2015 * Visiting Fellow, University of Southampton, Centre for Banking, Finance and Sustainable Development, Southampton Business School, Building 2, Southampton SO17 1TR, [email protected]; Associate Director, Economy and Finance Programme, The New Economics Foundation (NEF), 10 Salamanca Place, London SE1 7HB, [email protected]. The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2015 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT Historically high levels of private and public debt coupled with already very low short-term interest rates appear to limit the options for stimulative monetary policy in many advanced economies today. One option that has not yet been considered is monetary financing by central banks to boost demand and/or relieve debt burdens. We find little empirical evidence to support the standard objection to such policies: that they will lead to uncontrollable inflation. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

DEBASEMENTS in EUROPE and THEIR CAUSES, 1500-1800 Ceyhun Elgin, Kivanç Karaman and Şevket Pamuk Bogaziçi University, Istanbu

June 2015 DEBASEMENTS IN EUROPE AND THEIR CAUSES, 1500-1800 Ceyhun Elgin, Kivanç Karaman and Şevket Pamuk Bogaziçi University, Istanbul [email protected] Abstract: The large literature on prices and inflation in early modern Europe has not sufficiently distinguished between price increases measured in grams of silver and price increases due to debasements. This has made it more difficult to understand the underlying causes of the variation across Europe in price stability and more generally macroeconomic stability. This paper first provides a continent-wide perspective on the proximate causes of inflation in early modern Europe. We establish that in northwestern Europe debasements were limited and price increases measured in grams of silver were the leading cause of inflation. Elsewhere, especially in eastern Europe, debasements were more freequent and were the leading proximate cause of price increases. The existing literature on debasements based mostly on the experience of western Europe emphasizes both fiscal and monetary causes. We then investigate the fiscal causes of debasements by making use of a new dataset covering 11 countries from western, southern and eastern parts of the continent for the period 1500 to 1800. Our probit regressions suggest that fiscal demands of warfare, low fiscal capacity as measured by tax revenues, and lack of constaints on the executive power were all associated with higher likelihood of debasements for early modern Europe as a whole. Our empirical analysis also points to significant differences between the west and the east of the continent in terms of the causes of debasements. Warfare and low fiscal capacity appear as the leading causes of debasements in eastern Europe (Austria, Poland, Russia and the Ottoman empire). -

By “Fancy Or Agreement”: Locke's Theory of Money and the Justice of the Global Monetary System

Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, Volume 6, Issue 1, Spring 2013, pp. 49-81. http://ejpe.org/pdf/6-1-art-3.pdf By “fancy or agreement”: Locke’s theory of money and the justice of the global monetary system LUCA J. UBERTI American University in Kosovo Rochester Institute of Technology Abstract: Locke argues that the consent of market participants to the introduction of money justifies the economic inequalities resulting from monetarization. This paper shows that Locke’s argument fails to justify such inequalities. My critique proceeds in two parts. Regarding the consequences of the consent to money, neo-Lockeans wrongly take consent to justify inequalities in the original appropriation of land. In contrast, I defend the view that consent can only justify inequalities resulting directly from monetized commercial exchange. Secondly, regarding the nature of consent, neo-Lockeans uncritically accept Locke’s account of money as a natural institution. In contrast, I argue that money is an irreducibly political institution and that monetary economies cannot develop in the state of nature. My political account of money has far-reaching implications for the normative analysis of the global monetary system and the justification of the economic inequalities consequent upon it. Keywords: Locke, metallism, chartalism, consent, equality, global monetary system JEL Classification: B11, E42, Z10 The extent to which Locke’s principles of justice (or ‘Law of Nature’) justifies permissible material inequalities is a long-standing terrain of contention in the neo-Lockean tradition. While some critics (e.g., left- libertarians) have argued that the way Locke’s law regulates original resource appropriation contains extensive egalitarian provisions (Vallentyne, et al. -

Commodity Market Integration, 1500–2000

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Globalization in Historical Perspective Volume Author/Editor: Michael D. Bordo, Alan M. Taylor and Jeffrey G. Williamson, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-06598-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bord03-1 Conference Date: May 3-6, 2001 Publication Date: January 2003 Title: Commodity Market Integration, 1500–2000 Author: Ronald Findlay, Kevin H. O'Rourke URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c9585 1 Commodity Market Integration, 1500–2000 Ronald Findlay and Kevin H. O’Rourke 1.1 Introduction This paper provides an introduction to what is known about trends in in- ternational commodity market integration during the second half of the second millennium. Throughout, our focus is on intercontinental trade, since it is the emergence of large-scale trade between the continents that has especially distinguished the centuries following the voyages of da Gama and Columbus. This is by no means to imply that intra-European or intra- Asian trade was in any sense less significant; it is simply a consequence of the limitations of space. How should we measure integration? Traditional historians and modern trade economists tend to focus on the volume of trade, documenting the growth of trade along particular routes or in particular commodities, or trends in total trade, or the ratio of trade to output. While such data are in- formative, and while we cite such data in this paper, ideally we would like to have data on the prices of identical commodities in separate markets. -

Unconventional Monetary Policies and Central Bank Profits: Seigniorage As Fiscal Revenue in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis

Working Paper No. 916 Unconventional Monetary Policies and Central Bank Profits: Seigniorage as Fiscal Revenue in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis by Jörg Bibow* Levy Economics Institute of Bard College and Skidmore College October 2018 * The author gratefully acknowledges comments on an earlier draft from: Forrest Capie, Charles Goodhart, Perry Mehrling, Bernard Shull, Andrea Terzi, Walker Todd, and Andy Watt, as well as research assistance by Julia Budsey and Naira Abdula. The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2018 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT This study investigates the evolution of central bank profits as fiscal revenue (or: seigniorage) before and in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008–9, focusing on a select group of central banks—namely the Bank of England, the United States Federal Reserve System, the Bank of Japan, the Swiss National Bank, the European Central Bank, and the Eurosystem (specifically Deutsche Bundesbank, Banca d’Italia, and Banco de España)—and the impact of experimental monetary policies on central bank profits, profit distributions, and financial buffers, and the outlook for these measures going forward as monetary policies are seeing their gradual “normalization.” Seigniorage exposes the connections between currency issuance and public finances, and between monetary and fiscal policies.