Community Representation Report: Boards and Commissions in the San Diego Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOARD of DIRECTORS AGENDA Friday, January 23, 2004

Board Members Ron Morrison, Chairman Councilmember, National City Mickey Cafagna, Vice Chairman Mayor, Poway Ramona Finnila Mayor Pro Tem, Carlsbad Steve Padilla Mayor, Chula Vista BOARD OF DIRECTORS Phil Monroe Mayor Pro Tem, Coronado AGENDA Crystal Crawford Councilmember, Del Mar Mark Lewis Mayor, El Cajon Christy Guerin Councilmember, Encinitas Friday, January 23, 2004 Lori Holt Pfeiler 9 a.m. Mayor, Escondido SANDAG Patricia McCoy th Mayor Pro Tem, Imperial Beach 401 B Street, 7 Floor Barry Jantz Downtown San Diego Councilmember, La Mesa Mary Sessom Mayor, Lemon Grove Jack Feller Councilmember, Oceanside Dick Murphy Mayor, San Diego AGENDA HIGHLIGHTS Jim Madaffer Councilmember, San Diego Corky Smith • PROGRESS ON CONSOLIDATION UNDER SB 1703 Mayor, San Marcos Hal Ryan • FY 2005 TRANSIT CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT Councilmember, Santee PROGRAM Joe Kellejian Mayor, Solana Beach • IMPACTS OF GOVERNOR’S BUDGET PROPOSAL Morris Vance Mayor, Vista Dianne Jacob Chairman, County of San Diego Advisory Members Victor Carrillo, Supervisor Imperial County PLEASE TURN OFF CELL PHONES DURING THE MEETING Pedro Orso-Delgado, District Director California Department of Transportation YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE SANDAG BOARD MEETING BY Leon Williams, Chairman Metropolitan Transit VISITING OUR WEB SITE AT WWW.SANDAG.ORG Development Board Judy Ritter, Chair North San Diego County Transit Development Board CAPT Christopher Schanze, USN MISSION STATEMENT U.S. Department of Defense The 18 cities and county government are SANDAG serving as the forum for regional decision-making. Jess Van Deventer, Commissioner SANDAG builds consensus, makes strategic plans, obtains and allocates resources, and provides San Diego Unified Port District information on a broad range of topics pertinent to the region’s quality of life. -

The Housing Affordability Crisis

Addressing The Housing Affordability Crisis San Diego Housing Production Objectives 2018-2028 We’re About People “Increase the number of housing opportunities that serve low-income and homeless individuals and families in the City of San Diego” Strategic Plan Goal San Diego Housing Commission September 9, 2016 Message from the President & CEO September 21, 2017 Identifying solutions to the housing affordability crisis in the City of San Diego requires innovation, collaboration, and the will to take action. I commend and thank our City, County, State and Federal elected officials, as well as the San Diego Housing Commission (SDHC) Board of Commissioners, for demonstrating their commitment to all three. When SDHC released our landmark report, “Addressing the Housing Affordability Crisis: An Action Plan for San Diego,” on November 25, 2015, we identified 11 recommended actions at the Local, State and Federal levels to reduce housing development costs and to increase production. To date, action has been taken on nine of these 11 recommendations, including the first—to set annual goals for housing production. To facilitate the creation of these goals for the City of San Diego, SDHC, in collaboration with San Diego City Councilmembers Scott Sherman and David Alvarez, the Chair and Vice Chair, respectively, of the City Council’s Smart Growth and Land Use Committee, studied the City’s overall housing production needs, its current supply, as well as its capacity for additional homes. Although the City of San Diego’s housing needs are even higher than previously estimated, the good news is that the City has enough capacity to create sufficient housing to meet our 10-year needs, as identified in this report. -

Hotel Churchill Grand Reopening September 19, 2016 Message from SDHC President & CEO Richard C

We’re About People Hotel Churchill Grand Reopening September 19, 2016 Message from SDHC President & CEO Richard C. Gentry September 19, 2016 Dear Friends and Colleagues, The preservation of affordable housing at the historical Hotel Churchill is a testament to the collaborative efforts of the San Diego Housing Commission (SDHC) and our partners to find innovative solutions to address homelessness. I thank those who made this grand reopening possible, including our congressional delegation – U. S. Representatives Scott Peters, Juan Vargas, and Susan Davis, and our partners at the State and County, respectively Assemblymember Toni Atkins and Board of Supervisors Chairman Ron Roberts. In addition, I commend Mayor Kevin L. Faulconer, City Councilmember Todd Gloria, whose district includes Hotel Churchill, and the full San Diego City Council for their support. With this renovation, we have created 72 affordable rental housing studios that will remain affordable for 65 years. The renovation of Hotel Churchill is also a key component of HOUSING FIRST – SAN DIEGO, SDHC’s landmark three-year Homelessness Action Plan (2014-2107), which was announced on November 12, 2014, at the Hotel Churchill. I am proud of the staff at SDHC and Housing Development Partners (HDP), SDHC’s nonprofit affiliate, for their dedication to provide housing opportunities for homeless San Diegans. HDP served as the developer for this project, working closely with the construction team. The Hotel Churchill is a shining example of ingenuity, foresight, and innovation to address homelessness. Sincerely, Richard C. Gentry President & CEO 2 San Diego Housing Commission 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS U.S. Senate City of San Diego U.S. -

ELECTION DAY Results 1911-2018

ELECTION DAY Results 1911-2018 Compiled by the Office of the City Clerk Kerry Bigelow, MMC, City Clerk SPECIAL MUNICIPAL ELECTION November 6, 2018 Registered Voters: 140,099 Number of precincts: 122 Vote-by-mail ballots cast: 53,137 Polling place ballots cast: 27,393 Total ballots cast 80,530 Voter Turnout: 57.5% Election Cost: $153,047 (Mayor - $28,205; City Attorney – $28,205; District 1 – $8,200; District 2 – $7,014; Measure Q – $81,423) Nominees for Mayor Votes Percent Result (4-year term) Mary Casillas Salas 54,062 71.86% Won Hector Gastelum 21,175 28.14% Lost Nominees for Council, District 1 Votes Percent Result (4-year term) John McCann 11,945 51.66% Won Mark Bartlett 11,178 48.34% Lost Nominees for Council, District 2 Votes Percent Result (4-year term) Jill M. Galvez 8,871 52.50% Won Steve Stenberg 8,027 47.50% Lost Nominees for City Attorney Votes Percent Result (4-year term) Glen Googins 43,333 60.32% Won Andrew Deddeh 28,501 39.68% Lost Ballot Measure Yes No Result Measure Q - Shall the measure to impose a business 48,607 26,965 Passed license tax of at least 5%, and up to 15%, of gross (64.32%) (35.68%) receipts on cannabis (marijuana) businesses, and at least $5, and up to $25, per square foot on space dedicated to cannabis cultivation, to raise an estimated $6,000,000 per year, until voters change or repeal it, to fund general City services, including enforcement efforts against cannabis businesses that are operating illegally, be adopted? 120 GENERAL MUNICIPAL ELECTION June 5, 2018 Registered Voters: 133,776 Number of precincts: 117 Vote-by-mail ballots cast: 28,615 Polling place ballots cast: 11,581 Total ballots cast 40,196 Voter Turnout: 30.05% Election Cost: $188,819 (Mayor - $51,968; District 2 – $14,779; Measure A – $123,532) Nominees for Mayor Votes Percent Result (4-year term) Mary Casillas Salas 24,572 62.48% Run-off Hector Raul Gastelum 6,676 16.98% Run-off Daniel Schreck 4,408 11.21% Lost Arthur Kende 3,547 9.02% Lost Nominees for Council, District 2 Votes Percent Result (4-year term) Steve Stenberg 2,521 25.80% Run-off Jill M. -

Joint Hearing with the Special Committee on Pandemic Emergency Response

JOINT HEARING WITH THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON PANDEMIC EMERGENCY RESPONSE “The Impact of COVID-19 in California’s Border Region” California State Capitol Senate Chambers 10am Liliana Ferrer Is the Consul General of Mexico in Sacramento, California; has been a career member of the Mexican Foreign Service since 1992. From October 2013 to May 2017, she was Deputy Chief of Mission at the Embassy of Mexico in Paris. Prior to assuming this role, she was Section Chief of Political and Border Affairs at the Mexican Embassy in Washington D.C. from 2011 to 2014, where she also served as a Congressional Affairs Officer (liaison to the House of Representatives) from 2007 to 2011 and Deputy Chief of Mission from 2005 to 2007. Prior to this position at the Embassy in DC, she spent a year at Harvard University as a member of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs doing research on lobbying in the United States. In Mexico City, she has served as: Spokesman of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Special Adviser to the Assistant Secretary for Economic Affairs and International Cooperation; and as Director of Bilateral Relations of the United States. She has also been commissioned at the Consulates of Mexico in San Diego and Los Angeles as Consul for Economic, Political and Community Affairs, and in Guatemala City as Deputy Consul General of Mexico. She holds a BA in International Relations from the University of California, Davis, and a Masters in International Affairs from the Pacific from the University of California, San Diego, where she received a pre-doctorate scholarship at the Center for US / Mexican Studies. -

6/27/2017 Honorable Mayor Kevin Faulconer and Councilmembers City of San Diego 202 C St. San Diego, CA 92101 RE: Support For

6/27/2017 Honorable Mayor Kevin Faulconer and Councilmembers City of San Diego 202 C St. San Diego, CA 92101 RE: Support for Community Choice Energy (CCE) Dear Mayor Faulconer and Council, Thank you for taking a leading role in addressing climate change and moving our city toward a 100% clean energy future. Our business supports the City's decision to move forward with Community Choice Energy. Community choice energy is essential for achieving our Climate Action Plan goals. Community choice gives San Diego businesses local control over our energy future, helps stabilize or reduce our rates, and provides us with the freedom to choose the source of our electricity. We are particularly interested in the opportunity for a local community choice program to buy increasing amounts of power from local sources, supporting local jobs and local economic development. We believe the city should join 3.3 million Californians in the movement for clean energy, clean jobs, and local choice through Community Choice Energy. Thank you for supporting the freedom of energy choice for San Diego. We look forward to partnering with you on creating a stronger, more resilient clean energy future. Sincerely, Jacob McKean Founder/CEO Modem Times Beer CC: Kevin Faulconer, Mayor Myrtle Cole, Council President Mark Kersey, Council President Pro Tern Barbara Bry, Councilmember Lorie Zapf, Councilmember Christopher Ward, Councilmember Chris Cate, Councilmember Scott Sherman, Councilmember David Alvarez, Councilmember Georgette Gomez, Councilmember MODERN TIMES BEER 3725 GREENWOOD ST WWW.MODERNTIMESBEER . COM 619-546-9694SAN DIEGO, CA 92110 . -

Council District 2 Candidate Statements CITY of SAN DIEGO CANDIDATE’S STATEMENT of QUALIFICATIONS

Council District 2 Candidate Statements CITY OF SAN DIEGO CANDIDATE’S STATEMENT OF QUALIFICATIONS City Name: CITY OF SAN DIEGO (ALL CAPS) Office Title: San Diego City Council District 2 (Upper & Lower) Candidate Name: JENNIFER CAMPBELL (ALL CAPS) (Use “Block Paragraphs/Justified, Single Space” format. Type within the box using a pitched font such as courier. Word count starts here:) Jennifer Campbell, MD Medical Doctor/Professor The doctor on call to FIX city hall! ENDORSED BY Congressman Scott Peters State Senator Toni Atkins Assemblyman Todd Gloria Councilmember Barbara Bry Planned Parenthood Action Fund Sierra Club Dr. Jen Campbell strengthens our community and has the experience to succeed. ● Respected family physician and educator. ● Volunteer dedicated to equal rights, treating homeless vets, and community representation. ● Past Executive Board Member of the Clairemont Town Council and the San Diego Human Dignity Foundation. Dr. Jen is running because San Diego needs accountability and action instead of indifference and delay. ● Downtown interests push through costly pet projects while ignoring our neighborhoods. ● Our city was unprepared for the Hepatitis A outbreak and a deadly flu season. ● Housing affordability and skyrocketing rents are driving away our next generation. Dr. Jen will fight for the residents of District 2. ● Ensure vacation rental regulation is fully enforced. ● Tackle our crumbling infrastructure and getting our fair share of city services. ● Implement nationally proven programs to reduce homelessness. ● Protect the beauty of our beaches and bays and safeguard their accessibility. “I’m here to provide the greatest care for our communities. District 2 needs responsible, intelligent leadership to secure our future.” -Dr. -

AGENDA Vacant (Representing Imperial County)

Members Vacant (Representing South County) Greg Cox, Vice Chair Supervisor, County of San Diego Vacant (Representing North County Coastal) Vacant BORDERS (Representing North County Inland) John Minto COMMITTEE Councilmember, City of Santee (Representing East County) AGENDA Vacant (Representing Imperial County) David Alvarez Councilmember, City of San Diego Friday, January 28, 2011 Alternates 12:30 to 2:30 p.m. Rudy Ramirez Councilmember, City of Chula Vista SANDAG Board Room (Representing South County) 401 B Street, 7th Floor Pam Slater-Price Chairwoman, County of San Diego San Diego Jim Wood Mayor, City of Oceanside (Representing North County Coastal) Vacant AGENDA HIGHLIGHTS (Representing North County Inland) David Allan Vice Mayor, City of La Mesa • DRAFT 2050 RTP: TRIBAL, BINATIONAL, AND (Representing East County) INTERREGIONAL COMPONENTS John Moreno Mayor, City of Calexico (Representing Imperial County) • SAN YSIDRO COMMUNITY PLAN UPDATE Sherri Lightner Councilmember, City of San Diego • UPDATE ON THE SAN DIEGO-TIJUANA AIRPORT Advisory Members CROSSBORDER FACILITY Thomas Buckley Councilmember, City of Lake Elsinore (Representing Riverside County) Jim Dahl Mayor Pro Tem, City of San Clemente (Representing Orange County) Remedios Gómez-Arnau PLEASE TURN OFF CELL PHONES DURING THE MEETING Consul General, Consulate General of Mexico Howard Williams/Elsa Saxod San Diego County Water Authority YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE BORDERS COMMITTEE Laurie Berman MEETING BY VISITING OUR WEB SITE AT WWW.SANDAG.ORG District 11 Director, Caltrans Vacant Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association MISSION STATEMENT Richard Macias Director of Planning, Southern California Association The Borders Committee provides oversight for planning activities that impact the borders of the of Governments San Diego region (Orange, Riverside and Imperial Counties, and the Republic of Mexico) as well as government-to-government relations with tribal nations in San Diego County. -

Housing Authority of the City of San Diego Regular Meeting Minutes Tuesday, November 13, 2018 City Council Chambers – 12Th Floor

HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO REGULAR MEETING MINUTES TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2018 CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – 12TH FLOOR The Regular Meeting of the Housing Authority of the City of San Diego was called to order at 3:42 p.m. ATTENDANCE Present: Council President Myrtle Cole, District 4 Council President Pro Tem Barbara Bry, District 1 Councilmember Lorie Zapf, District 2 Councilmember Chris Ward, District 3 Councilmember Mark Kersey, District 5 Councilmember Chris Cate, District 6 Councilmember Scott Sherman, District 7 Councilmember David Alvarez, District 8 Councilmember Georgette Gómez, District 9 Non-Agenda Public Comment: Martha Welch spoke about affordable housing. Kathryn Rhodes spoke about affordable housing. Approval of Housing Authority Minutes: The minutes of the Regular Housing Authority Meeting of September 18, 2018, were approved on a motion by Council President Cole, seconded by Councilmember Sherman, and passed by a vote of 9-0. DISCUSSION AGENDA: ITEM 1: HAR18-021 Approval of the Contract between the San Diego Housing Commission and Family Health Centers to operate the City of San Diego’s Housing Navigation Center at 1401 Imperial Avenue, San Diego, California 92113; Approval of an MOU with the City of San Diego regarding the Housing Navigation Center; and Taking Related Actions Keely Halsey, Chief of Homelessness Strategies, City of San Diego, and Lisa Jones, Senior Vice President, Homeless Housing Innovations, San Diego Housing Commission, presented the request for approval. Motion by Council President Cole to approve the staff-recommended actions, as amended to include the Independent Budget Analyst’s recommendations regarding the contract, which are as follows: • The Housing Authority is notified when partner agency commitments are secured, schedules reflecting when they will be on-site, and services they will be providing at the Housing Navigation Center. -

2019 Methamphetamine Use by San Diego County Arrestees 2

2019 Methamphetamine Use by San Diego County Arrestees Data from the SANDAG Substance Abuse Monitoring program in brief Research findings from the Criminal Justice Clearinghouse Cj 401 B STREET, SUITE 800 | SAN DIEGO, CA 92101-4231 | T (619) 699-1900 | F (619) 699-6905 | SANDAG.ORG/CJ Board of Directors The 18 cities and county government are SANDAG serving as the forum for regional decision-making. SANDAG builds consensus; plans, engineers, and builds public transit; makes strategic plans; obtains and allocates resources; and provides information on a broad range of topics pertinent to the region’s quality of life. Chair Vice Chair Executive Director Hon. Steve Vaus Hon. Catherine Blakespear Hasan Ikhrata City of Carlsbad City of Santee Hon. Cori Schumacher, Councilmember Hon. John Minto, Mayor (A) Keith Blackburn, Mayor Pro Tem (A) Hon. Ronn Hall, Councilmember (A) Hon. Priya Bhat-Patel, Councilmember (A) Hon. Rob McNelis, Councilmember City of Chula Vista City of Solana Beach Hon. Mary Salas, Mayor Hon. David A. Zito, Councilmember (A) Hon. Steve Padilla, Councilmember (A) Hon. Jewel Edson, Mayor (A) Hon. John McCann, Councilmember (A) Hon. Kristi Becker, Councilmember City of Coronado City of Vista Hon. Richard Bailey, Mayor Hon. Judy Ritter, Mayor (A) Hon. Bill Sandke, Councilmember (A) Hon. Amanda Rigby, Deputy Mayor (A) Hon. Mike Donovan, Councilmember (A) Hon. Joe Green, Councilmember City of Del Mar County of San Diego Hon. Ellie Haviland, Mayor Hon. Jim Desmond, Vice Chair (A) Hon. Dwight Worden, Councilmember (A) Hon. Dianne Jacob, Supervisor (A) Hon. Dave Druker, Councilmember Hon. Kristin Gaspar, Supervisor City of El Cajon (A) Hon. -

Annual List of Federally Obligated Projects FFY 2020

Annual list of Federally Obligated Projects FFY 2020 (October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2020) Richard Radcliffe Financial Analyst II December 2020 Board of Directors The 18 cities and county government are SANDAG serving as the forum for regional decision-making. SANDAG builds consensus; plans, engineers, and builds public transit; makes strategic plans; obtains and allocates resources; and provides information on a broad range of topics pertinent to the region’s quality of life. CHAIR VICE CHAIR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Hon. Steve Vaus Hon. Catherine Blakespear Hasan Ikhrata CITY OF CARLSBAD CITY OF SANTEE Hon. Cori Schumacher, Councilmember Hon. John Minto, Mayor (A) Hon. Keith Blackburn, Mayor Pro Tem (A) Hon. Ronn Hall, Councilmember (A) Hon. Priya Bhat-Patel, Councilmember (A) Hon. Rob McNelis, Councilmember CITY OF CHULA VISTA CITY OF SOLANA BEACH Hon. Mary Salas, Mayor Hon. David A. Zito, Councilmember (A) Hon. Steve Padilla, Councilmember (A) Hon. Jewel Edson, Mayor (A) Hon. John McCann, Councilmember (A) Hon. Kristi Becker, Councilmember CITY OF CORONADO CITY OF VISTA Hon. Richard Bailey, Mayor Hon. Judy Ritter, Mayor (A) Hon. Bill Sandke, Councilmember (A) Hon. Amanda Rigby, Deputy Mayor (A) Hon. Mike Donovan, Councilmember (A) Hon. Joe Green, Councilmember CITY OF DEL MAR COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO Hon. Ellie Haviland, Mayor Hon. Jim Desmond, Vice Chair (A) Hon. Dwight Worden, Councilmember (A) Hon. Dianne Jacob, Chair (A) Hon. Dave Druker, Councilmember Hon. Kristin Gaspar, Supervisor (A) Hon. Greg Cox, Chair CITY OF EL CAJON (A) Hon. Nathan Fletcher, Supervisor Hon. Bill Wells, Mayor (A) Hon. Steve Goble, Deputy Mayor ADVISORY MEMBERS CITY OF ENCINITAS Hon. -

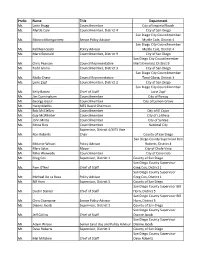

Prefix Name Title Department Ms. Lorie Bragg Councilmember City of Imperial Beach Ms

Prefix Name Title Department Ms. Lorie Bragg Councilmember City of Imperial Beach Ms. Myrtle Cole Councilmember, District 4 City of San Diego San Diego City Councilmember Ms. Monica Montgomery Senior Policy Advisor Myrtle Cole, District 4 San Diego City Councilmember Ms. Kathleen Sadd Policy Advisor Myrtle Cole, District 4 Ms. Marti Emerald Councilmember, District 9 City of San Diego San Diego City Councilmember Mr. Chris Pearson Council Representative Marti Emerald, District 9 Mr. Todd Gloria Councilmember, District 3 City of San Diego San Diego City Councilmember Ms. Molly Chase Council Representative Tood Gloria, District 3 Ms. Lorie Zapf Councilmember, District 2 City of San Diego San Diego City Councilmember Ms. Kelly Batten Chief of Staff Lorie Zapf Mr. Jim Cunningham Councilmember City of Poway Mr. George Gastil Councilmember City of Lemon Grove Mr. Harry Mathis MTS Board Chairman Mr. Bob McClellan Councilmember City of El Cajon Mr. Guy McWhirter Councilmember City of La Mesa Mr. John Minto Councilmember City of Santee Ms. Mona Rios Councilmember National City Supervisor, District 4/MTS Vice Mr. Ron Roberts Chair County of San Diego San Diego County Supervisor Ron Ms. Melanie Wilson Policy Advisor Roberts, District 4 Ms. Mary Salas Mayor City of Chula Vista Mr. Mike Woiwode Councilmember City of Coronado Mr. Greg Cox Supervisor, District 1 County of San Diego San Diego County Supervisor Ms. Pam O'Neil Chief of Staff Greg Cox, District 1 San Diego County Supervisor Mr. Michael De La Rosa Policy Advisor Greg Cox, District 1 Mr. Bill Horn Supervisor, District 5 County of San Diego San Diego County Supervisor Bill Mr.