Marry for What? Caste and Selection in Modern India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

700 032 September 7, 2021 a D M I S S I O N B.A

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY KOLKATA – 700 032 September 7, 2021 A D M I S S I O N B.A. (HONOURS) COURSE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE SESSION 2021 - 2022 The Lists are provisional and are subject to: i. fulfilling the eligibility criteria as notified earlier. ii. verification of the equivalence of marks/degrees from other Boards/Councils to those of the West Bengal council of Higher Secondary Education /Other equivalent Board/Council, wherever applicable. iii. correction in the merit position due to error, if any. All admissions are provisional. As per the order of Govt. of West Bengal [order no: 706-Edn(CS)/10M-95/14 dated 13/7/2021], all the original documenmts of applicants will be verified when they report for classes at University campus. Provisional admission of a candidate will stand cancelled if the documents are found not in conformity with the declaration in the forms submitted on-line. If at the time of document verification, it is found by the university authority that a student does not satisfy the eligibility criteria, s/he will not be considered for admission, even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission. a student does not have completed result at +2 level, his/her application shall be cancelled even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission. a candidate has already graduated from a college with a Bachelors degree, her/his application shall be cancelled even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission, since s/he cannot enrol herself/himself for another Bachelors degree course. Those candidates who have -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

BJP Sonarbanglasonkolpopotr

NDA government has been able to complete over 950 km of highways in West Bengal, with over 2250 km highway development in the pipeline. 24 lakh households have been built under PM Awas Yojana, with over 10 lakh households receiving clean drinking water and 89 lakh women having access to clean cooking gas. Our achievements speak for themselves, but we realise that there is still a long way to go. To travel this long way we have reached out to the people of West Bengal and together with them we have created a vision for Sonar Bangla. Our vision for Sonar Bangla is one that seeks to make West Bengal the righul inheritor of its past glory and make sure its fruits reach everyone in the state in a fair and just manner. We want a Sonar Bangla which is recognized the world over for its culture and glorious history. A Sonar Bangla which treats all its citizens equally and where government’s schemes reach them without any discrimination or favour. A Sonar Bangla which ensures that people don't have to live under the fear of political violence, maa raj, and gundaraj. A Sonar Bangla which is a leader in all aspects of economic and social development. A Sonar Bangla which enables its youth to achieve their full potential A Sonar Bangla which empowers its women to be leaders of development A Sonar Bangla which takes care of all its people by providing accessible and quality healthcare and education A Sonar Bangla which has the infrastructure that rivals the best amongst the world A Sonar Bangla which is home to people of all walks of life who live in harmony with each other and enable each other and the whole state to prosper and progress together A Sonar Bangla which is a place where in Gurudev’s words “Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high” We believe that it is Sonar Bangla’s Purboday that will catalyse India’s Bhagyoday. -

The Mahishyas : the Wrangle Over Caste-Indentity

Karatoya: NBU J. Hist. Vol. 5 :72-75(2012) ISSN : 2229-4880 The Mahishyas : The Wrangle over Caste-indentity Sankar Kumar Das The history of Midnapur particularly of its south and south-west regions is in one sense the history of one movement in many respects. It is mostly the history of the movement of the Mahishyas, a caste community, for establishing their caste-position and for cultural assertion and also for political resurgence. The Mahishya claimed that they were a 'pure caste' from time immemorial. They were all along a land-holding and land occupying cultivating people divided mostly in three classes viz landlords, tenants and agricultural labourers. During the Turko-Afghan and the Mughal rules the socio-economic set-up of the community, in spite of little communal troubles and administrative transformations, was quiet and placid, and it was in no way detrimental to their material and religious interests. With the establishment of the British rule in Bengal and the introduction of the Permanent Settlement the agrarian economy of the region was changed to a very great extent. It was then there began the rise and growth ofnew land-holders like zamindars andjotedars in the Contai and Tamluk subdivisions. Some of them again securing pattanis and pattas in the Sundarbans in the neighbouring 24 Parganas became latdars and chakdars. Some of the advanced Mahishyas took business as their profession and started business relations with the East India Company in respect of salt, mulberry and silk trades. Others again took services in the Company's merchant offices. 1 As a result a certain section of the Mahishya community of Midnapur particularly the Calcutta-based lawyers and trders thrived plausibly. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

Chief Engineer (HQ.), Public Works Directorate Government of West

Chief Engineer (HQ.), Io NABANNA.8th Floor. Public Works Directorate 325, Sarat Chatterjee Road, Shibpur, Government of West Bengal Howrah -711102 Tel No: 033-2214-3619, Fax No: 033-2214-3343 emailld:[email protected] No. 1227/CE(HQ)/PWD Date: 02.09.2020 ORDER The following noted Junior Engineers (Civil) under the P.W.D.• as tabulated below are hereby transferred from their present place of posting and on such transfer they are posted at the office as indicated against their names. with immediate effect and until further order. T.AID.A. is admissible as per rule. SI. Name Present Place of Posting. Posting on Tranfer. No. Estimator under the office of the Barrackpore Sub-Division- II, under I Shri Sanjoy Basu. Superintendent, Governor's Esate, Barrackpore Division, P.W.Dte. W.B. Kolkata Raj Bhavan Sub-Division Barrackpore Sub-Division- II, Shri Tarun Kumar 2 under Superintendent, Governor's under Barrackpore Division, Sharma Sarkar. Esate, W.B. P.W.Dte. Bidhannagar West Sub-Division-1Il Shri Ashim Estimator,Birbhum Division, 3 under Bidhannagar West Sub- Bhowmik. P.W.Dte. Division. P.W.Dte. Durgapur Sub Division under Shri Basudev Western Circle, Social Sector, 4 Asansol Division, Social Chandra. P.W.Dte. Sector,P. W.Dte. Bidhannagar West Sub-Division-1Il Shri Manab Estimator, Asansol Division, Social 5 under Bidhannagar West Sub- Mondal. Sector, P.W.Dte. Division. P.W.Dte. Shri Swapan Kumar Estimator, Murshidabad Division, Office of the Chief Engineer, 6 Bera. Social Sector, P.W.Dte. Planning, P.W.Dte. Shri Dilip Office of the Chief Engineer, Estimator, Murshidabad Division, 7 Karmakar. -

Preliminary Pages.Qxd

State Formation and Radical Democracy in India State Formation and Radical Democracy in India analyses one of the most important cases of developmental change in the twentieth century, namely, Kerala in southern India, and asks whether insurgency among the marginalized poor can use formal representative democracy to create better life chances. Going back to pre-independence, colonial India, Manali Desai takes a long historical view of Kerala and compares it with the state of West Bengal, which like Kerala has been ruled by leftists but has not experienced the same degree of success in raising equal access to welfare, literacy and basic subsistence. This comparison brings historical state legacies, as well as the role of left party formation and its mode of insertion in civil society to the fore, raising the question of what kinds of parties can effect the most substantive anti-poverty reforms within a vibrant democracy. This book offers a new, historically based explanation for Kerala’s post- independence political and economic direction, drawing on several comparative cases to formulate a substantive theory as to why Kerala has succeeded in spite of the widespread assumption that the Indian state has largely failed. Drawing conclusions that offer a divergence from the prevalent wisdoms in the field, this book will appeal to a wide audience of historians and political scientists, as well as non-governmental activists, policy-makers, and those interested in Asian politics and history. Manali Desai is Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Kent, UK. Asia’s Transformations Edited by Mark Selden Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The books in this series explore the political, social, economic and cultural consequences of Asia’s transformations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg

Cultural Models Affecting Indian-English 'Matrimonials' and British-English Contact Advertisements with a View to Marriage: A Corpus-based Analysis Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Neuphilologischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von Sandra Frey 1 Dedicated to my husband and to my parents 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 13 1.1 Aims and Scope ................................................................................................ 14 1.2 Methods and Sources ........................................................................................ 15 1.3 Chapter Outline ................................................................................................ 17 1.4 Previous Scholarship ........................................................................................ 18 2 Matrimonials as a Text Type ................................................................................ 21 2.1 Definition and Classification ............................................................................ 21 2.2 Function ............................................................................................................ 22 2.3 Structure ........................................................................................................... 25 3 The Data -

Download the File As PDF Format

WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES VOLUME – I (Containing 1 st , 2 nd & 3 rd Reports) FIRST REPORT : Name of the Class INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. KAPALI ….. 2. BAISHYA KAPALI ….. 3. KURMI ….. 4. SUTRADHAR ….. 5. KARMAKAR ….. 6. KUMBHAKAR ….. 7. SWARNAKAR ….. 8. TELI ….. 9. NAPIT 10. YOGI-NATH ….. 11. GOALA GOPE ….. 12. MOIRA-MODAK (HALWAI) ….. 13. BARUJIBI ….. 14. SATCHASI ….. SECOND REPORT : Name of the Class INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. MALAKAR ….. 2. TANTI ….. 3. KANSARI ….. 4. SHANKHAKAR ….. 5. KOERI / KOIRI ….. 6. RAJU ….. 7. TAMBOLI / TAMALI ….. 8. NAGAR ….. 9. KARANI ….. 10. DHANUK ….. 11. SARAK ….. 12. JOLAH (ANSARI-MOMIN) ….. THIRD REPORT : INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. RONIWAR ….. 2. KOSTA / KOSTHA ….. 3. CHRISTIANS CONVERTED FROM SCHEDULED CASTES ….. WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES REPORT – I Representations have reached the West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes from various classes of citizens for inclusion in the lists of Backward Classes of the State. The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes has been set up by the Act of the State Legislature – “West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act, 1993 (West Bengal Act I of 1993)”. The Act provides “it is expedient to constitute a State Commission for Backward Classes other than the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and to provide matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”; and accordingly, the Act called “The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act” (hereinafter referred to as the Act) came to be enacted. In terms of the provisions contained in Section 3 of the Act the State Government has constituted this body to be known as “The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes“ (which will hereinafter be referred to as the Commission) to exercise the powers conferred on and to perform the functions assigned to the commission under the Act. -

“Temple of My Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal's

“Temple of my Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshi Community Aditya N. Bhattacharjee School of Religious Studies McGill University Montréal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2017 © 2017 Aditya Bhattacharjee Bhattacharjee 2 Abstract In this thesis, I offer new insight into the Hindu Bangladeshi community of Montreal, Quebec, and its relationship to community religious space. The thesis centers on the role of the Montreal Sanatan Dharma Temple (MSDT), formally inaugurated in 2014, as a community locus for Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshis. I contend that owning temple space is deeply tied to the community’s mission to preserve what its leaders term “cultural authenticity” while at the same time allowing this emerging community to emplace itself in innovative ways in Canada. I document how the acquisition of community space in Montreal has emerged as a central strategy to emplace and renew Hindu Bangladeshi culture in Canada. Paradoxically, the creation of a distinct Hindu Bangladeshi temple and the ‘traditional’ rites enacted there promote the integration and belonging of Bangladeshi Hindus in Canada. The relationship of Hindu- Bangladeshi migrants to community religious space offers useful insight on a contemporary vision of Hindu authenticity in a transnational context. Bhattacharjee 3 Résumé Dans cette thèse, je présente un aperçu de la communauté hindoue bangladaise de Montréal, au Québec, et surtout sa relation avec l'espace religieux communautaire. La thèse s'appuie sur le rôle du temple Sanatan Dharma de Montréal (MSDT), inauguré officiellement en 2014, en tant que point focal communautaire pour les Bangladeshis hindous de Montréal. -

Gradation List of WBPS Officers 2019.Xlsx

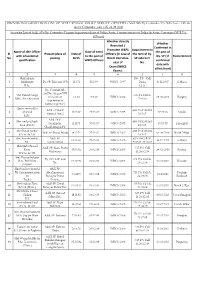

PROVISIONAL GRADATION LIST OF WEST BENGAL POLICE SERVICE OFFICERS (Addl. SPs/Dy.Commdts./ Dy. S.Ps/Asstt. CPs & Asstt. Commdts. ) AS ON 01-05-2019 Seniority List of Addl. SPs/Dy. Commdts./Deputy Superintendents of Police/Asstt. Commissioners of Police & Asstt. Commdts.(W.B.P.S. Officers) Whether directly Whether Recruited / Confirmed in Promotee WBPS Appointment in Name of tlhe Officer Date of entry the post of Sl. Present place of Date of Officers (In case of the rank of Dy. with educational to the post of Dy. SP ( If Home District No. posting Birth Direct Recruitee SP vide G.O. qualification WBPS Officers confirmed year of No. date with Exam.(WBCS effect from) Exam.) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shri Jayanta 138 - P.S. - Cell 1 Mukherjee Dy. SP, Telecom, WB 3.12.72 15.2.99 WBCS - 1997 Dated 14.12.2007 Kolkata B.Sc. 3.2.99. Dy. Commdt. IR. 2nd Bn., Siliguri WB Shri Rakesh Singh 956-P.S.Cell dt. 2 (to work on 5.5.72 8.8.06 WBCS-2004 08.08.2008 Hooghly MSC, Bio Chemistry 29.6.06 deputation to Kalimpong Dist.) Quazi Samsuddin Addl. SP.Rural 488-P.S.Cell dtd. 3 Ahamed 11.03.77 27.03.07 WBCS-2005 27.03.09 Malda Howrah Rural 20.3.07. M.Sc. Addl. DCP. Shri Amlan Ghosh 488-P.S.Cell dtd. 4 Serampore, 11.11.73 30.03.07 WBCS-2005 30.03.09 Jalpaiguri M.A.(Part I) 20.3.07. Chandannagar PC Shri Dipak Sarkar 488-P.S.Cell dtd. -

The West Bengal Backward Classes (Other Than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) (Reservation of Vacancies in Services and Posts) Act, 2012

Registered No. WB/SC-247 No. WB(Part-DI)/2013/SAR-7 Rottutta (IWO %%J AI "IQ Extraordinary Published by Authority CAITRA 4] MONDAY, MARCH 25, 2013 [SAKA 1935 PART EI—Acts of the West Bengal Legislature. GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOTIFICATION No. 533-L.-25th March, 2013.—The following Act of the West Bengal Legislature, having been assented to by the Governor, is hereby published for general information:— West Bengal Act XXXIX of 2012 THE WEST BENGAL BACKWARD CLASSES (OTHER THAN SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES) (RESERVATION OF VACANCIES IN SERVICES AND POSTS) ACT, 2012. [Passed by \ tiieWest Bengal Legislature.] [Assent of the Governor was first published in the Kolkata Gazette, Extraordinary, of the 25th March, 2013.] An Act to provide for the reservation of vacancies in services and posts for the Backward Classes of citizens other than the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. WHEREAS clause (4) of article 15 of the Constitution enables the State to make any special provisions for the advancement of any socially and educationally Backward Classes of citizens; AND WHEREAS clause (4) of article 16 of the Constitution enables the State to make any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any Backward Classes of citizens which in the opinion of the State is not adequately represented in the services under the State; 2 THE KOLKATA GAZE1TE., EXTRAORDINARY, MARCH 25, 2013 WART III • The West Bengal Backward Classes (Other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) (Reservation of