Hinduism to Your Child?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Sri Krishna Kathamrita

Sri Krishna Kathamrita Tav k-QaaMa*Ta& TaáJaqvNaMa( tava kathāmta tapta-jīvanam BinduBindu Fortnightly email mini-magazine from Gopal Jiu Publications Issue No. 20 9 January 2002 Śrī Saphalā Ekādaśī, 10 Nārāyaa, 515 Gaurābda s s • THE WICKED MIND t t RILA HAKTISIDDHANTA ARASWATI HAKUR RABHUPADA h S B S T P h g g i i • YASODA’S BELOVED SON l l RILA HAKTIVEDANTA WAMI RABHUPADA h S A. C. B S P h g g i i • KRISHNA GOES TO HERD THE COWS H H SRILA JIVA GOSWAMI’S ®Rī SA¦KALPA-KALPADRUMA · · · · · · · · THE WICKED MIND habituated to criticize others’ conduct will never prosper.” Let others do whatever they SRILA BHAKTISIDDHANTA SARASWATI like, I have no concern with them. I should THAKUR PRABHUPADA rather find fault with my own damned mind, This wicked mind, which is never and think like the vaiava mahājana [Srila to be trusted, should be broom- Thakur Bhaktivinode] who sings: sticked every morning with āmāra jīvana, sadā pāpe rata, such warning as, “Be not anx- nāhika puyera leśa ious to find fault with others, or para-sukhe dukhī, sadā mithyā-bhāśī, to proclaim thyself as a true, sin- para-dukha sukha-kara cere, bonafide bhakta, which certainly thou art Ever engaged in vicious activity, not.” In this connection, the advice of a vaiava And without the slightest trace of virtue in me, mahājana [Srila Narottam Das Thakur] is: A liar as I am, always sorry at others’ pleasures And merry at others’ sorrows, troubles and cares. karmī-jñānī michā-bhakta, nā habe tāte anurakta, — Śaraāgati 1.4 śuddha-bhajanete kara mana vraja-janera yei mata, tā’he ha’be anugata, We should always remember this song and ei se parama tattva dhana engage our mind ceaselessly in hari-bhajana. -

Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

S International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India Volume: 7 Abstract Disability has been the inescapable part of human society from ancient times. With the thrust of Issue: 1 disability right movements and development in eld of disability studies, the mythical past of dis- ability is worthy to study. Classic Indian Scriptures mention differently able character in prominent positions. There is a faulty opinion about Indian mythology is that they associate disability chie y Month: July with evil characters. Hunch backed Manthara from Ramayana and limping legged Shakuni from Mahabharata are negatively stereotyped characters. This paper tries to analyze that these charac- ters were guided by their motives of revenge, loyalty and acted more as dramatic devices to bring Year: 2019 crucial changes in plot. The deities of lord Jagannath in Puri is worshipped , without limbs, neck and eye lids which ISSN: 2321-788X strengthens the notion that disability is an occasional but all binding phenomena in human civiliza- tion. The social model of disability brings forward the idea that the only disability is a bad attitude for the disabled as well as the society. In spite of his abilities Dhritrashtra did face discrimination Received: 31.05.2019 because of his blindness. The presence of characters like sage Ashtavakra and Vamanavtar of Lord Vishnu indicate that by efforts, bodily limitations can be transcended. Accepted: 25.06.2019 Keywords: Karma, Medical model, Social model, Ability, Gender, Charity, Rights. -

Special Editor's Introduction: Three Tendencies in Indian Philosophy

SPECIAL EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION: THREE TENDENCIES IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY Devendra Nath Tiwari Going through the texts on Indian philosophical systems we find that the chief purpose of them is to find a solution against the conflicting ideas, digging out the problems, removing doubts of the opponents and getting freedom from them. Unless the thoughts are not clear they cannot be the part of our conduct. No problem is problem for itself; all problems are imposed at thought level and that is why they can be liquidated and removed by philosophical reflection. Removal of them provides bliss. The texts deal with cultivation of a wonderful capacity that accommodates conflicting situations for the greater purpose of living the life in harmony and peace. Great thoughts about the ways of life and the views of life dawn in Vedas and the classical texts. Philosophical systems originated as a safeguard for the maintenance and practice of those great ideas useful for the welfare of the universe. The history of great thoughts is at the same time the history of their critical observation, evaluation and refutation. Arguments in opposition and response in favour not only serve as breath of the protection of those thoughts but promoted Indian philosophical thinking to perfection of Indian culture that comprises the seed of almost all the reflective subtleties which serve as the novelty of the later thinking in India. Three types of tendency in Indian philosophical thinking are apparently observed. First to analyze and reflect on all the arguments popular at a time and then to observe that no argument given for proving the subject and object is steady. -

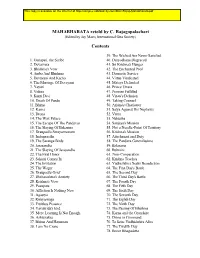

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Editors Seek the Blessings of Mahasaraswathi

OM GAM GANAPATHAYE NAMAH I MAHASARASWATHYAI NAMAH Editors seek the blessings of MahaSaraswathi Kamala Shankar (Editor-in-Chief) Laxmikant Joshi Chitra Padmanabhan Madhu Ramesh Padma Chari Arjun I Shankar Srikali Varanasi Haranath Gnana Varsha Narasimhan II Thanks to the Authors Adarsh Ravikumar Omsri Bharat Akshay Ravikumar Prerana Gundu Ashwin Mohan Priyanka Saha Anand Kanakam Pranav Raja Arvind Chari Pratap Prasad Aravind Rajagopalan Pavan Kumar Jonnalagadda Ashneel K Reddy Rohit Ramachandran Chandrashekhar Suresh Rohan Jonnalagadda Divya Lambah Samika S Kikkeri Divya Santhanam Shreesha Suresha Dr. Dharwar Achar Srinivasan Venkatachari Girish Kowligi Srinivas Pyda Gokul Kowligi Sahana Kribakaran Gopi Krishna Sruti Bharat Guruganesh Kotta Sumedh Goutam Vedanthi Harsha Koneru Srinath Nandakumar Hamsa Ramesha Sanjana Srinivas HCCC Y&E Balajyothi class S Srinivasan Kapil Gururangan Saurabh Karmarkar Karthik Gururangan Sneha Koneru Komal Sharma Sadhika Malladi Katyayini Satya Srivishnu Goutam Vedanthi Kaushik Amancherla Saransh Gupta Medha Raman Varsha Narasimhan Mahadeva Iyer Vaishnavi Jonnalagadda M L Swamy Vyleen Maheshwari Reddy Mahith Amancherla Varun Mahadevan Nikky Cherukuthota Vaishnavi Kashyap Narasimham Garudadri III Contents Forword VI Preface VIII Chairman’s Message X President’s Message XI Significance of Maha Kumbhabhishekam XII Acharya Bharadwaja 1 Acharya Kapil 3 Adi Shankara 6 Aryabhatta 9 Bhadrachala Ramadas 11 Bhaskaracharya 13 Bheeshma 15 Brahmagupta Bhillamalacarya 17 Chanakya 19 Charaka 21 Dhruva 25 Draupadi 27 Gargi -

Pluralism and Unity Religion and Philosophy

PLURALISM AND UNITY RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY Pluralism and Unity SWAMI ATMAPRIYANANDA his is a very interesting topic that number of books being published on this evokes in mind the analogy of the subject, especially the revolutionary Tocean and its waves. The ocean discoveries in physics at the turn of the 19th remains in the background while the waves century, namely the theory of Relativity and constantly rise and fall without disturbing the Quantum theory. The third is the the ocean. The waves find their unity in the psychological dimension which is also ocean. If you are asked what an ocean is you extremely important because man does not have to say—oceans are the waves. Without live on philosophy or science alone, he has a waves there is no ocean—it could be a lake mind which is constantly seeking meaning at the most. So the oceanness of the ocean is of life. Unless you find the meaning of life, given by the waves. life has no meaning at all. So we ask Rabindranath Tagore as you know, the fundamental questions about life like why remarkable poet of this age, had made a we are here? What we are? What is the goal wonderful statement in one of his poems and purpose of life? Where we come from, which has been translated into English. and finally where do we go? So, to seek There is the following dialogue between the meaning is a fundamental characteristic of ocean and the waves: human being. The fourth is the social dimension or the sociological dimension. -

Vedic Values

VEDIC VALUES Dr. Hema K. Kshirsagar Published by Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, Tirupati. 2018 ii FOREWORD VEDIC VALUES Indian culture is one of the richest and most diverse of its kind in the world as it has stimulated the growth and development of several philosophical systems and religious Dr. Hema K. Kshirsagar thoughts. This culture has exercised considerable influence over the spiritual life of the people all over the world. The oldest literature available with us are the Vedas. It T.T.D. Religious Publications Series No. 1288 was in the form of a lump before it's division. Bhagavan ©All Rights Reserved Vedavyasa has divided the lump of knowledge into four parts, i.e., Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva Vedas. The division was made with an intention as to make the Vedas to be understood by the readers and be followed by the readers and common First Edition - 2018 public to make their lives a fruitful one by following the path of Dharma. Vedic values written by Dr. Hema. K. Kshirsagar, is a Copies : 4000 wonderer treatise which carries good information about the values that are found in Vedas. The author has exemplified many values in brief but they are really good to be read by both elderly and children too. Published by Sri Anil Kumar Singhal, I.A.S., Hope this book will reach the coffee tables of all the Executive Officer, readers. Let our Ancient Culture reach the new generation, Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, and make a pathway for their colourful future. Tirupati. D.T.P: In the Service of Lord Venkateswara Publications Division T.T.D, Tirupati. -

Super Power Yajna Is Our Divine Father and Super Energy Gayatri Is Our Divine Mother

SUPER POWER YAJNA IS OUR DIVINE FATHER AND SUPER ENERGY GAYATRI IS OUR DIVINE MOTHER ORIGINALLY WRITTEN IN HINDI BY LATE YUGA RISHI SHRIRAM SHARMA ACHARYA (FOUNDER OF THE ALL WORLD GAYATRI FAMILY, WEBSITE: WWW.AWGP.ORG ) COMPILED AND PUBLISHED ON THE INTERNET BY MR ASHOK N. RAWAL TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY MS/ HEENA A. KAPADIA (M.Sc., M.Phil) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO SUPER POWER YAJNAS INTRODUCING VEDMURTI TAPONISHTHA YUGA RISHI PANDIT SHRIRAM SHARMA ACHARYA CHAPTER 1 WHAT EXACTLY ARE SUPER POWER YAJNAS? CHAPTER 2 WHY ARE SUPER ENERGY YAJNAS EXECUTED BY HUMAN BEINGS ONLY? CHAPTER 3 TRUE SACRED YAJNA SENTIMENTS ARE GOD WORSHIP AND PHILANTHROPHY CHAPTER 4 AUGMENTING AND AMPLYING GREAT DIVINE PRINCIPLES IN A MANIFOLD MANNER CHAPTER 5 MATERIAL BENEFITS ATTAINED VIA SUPER ENERGY SUPER POWER YAJNAS CHAPTER 6 AUGMENTING GOOD HEALTH AND WARDING OFF VARIOUS DISEASES VIA SUPER POWER YAJNAS CHAPTER 7 A DESCRIPTION OF SUPER POWER YAJNAS THAT ARE SPECIAL IN NATURE CHAPTER 8 GODDESS MOTHER GAYATRI WHO IMBUES HER DEVOTEES’ SOUL WITH SUPER DIVINE POWERS CHAPTER 9 TRIPADA OR 3 LEGGED SUPER ENERGY GAYATRI CHAPTER 10 THE PROFOUND MEANING OF SUPER POWER GAYATRI CHAPTER 11 SOLAR BASED SPIRITUAL PRACTICES CALLED SURYA SADHANA CHAPTER 12 REMAINING ALIVE VIA SOLAR ENERGY FOR 411 DAYS WITHOUT FOOD AND WATER CHAPTER 13 SOLAR BASED SPIRITUAL PRACTICES OR SURYA SADHANA-ITS TECHNIQUE AND METHODOLOGY CHAPTER 14 THE BRILLIANT SUN IS OUR VERY LIFE AND OUR PRANA ENERGY CHAPTER 15 THE BRILLIANT SUN BESTOWS ON US OUR VERY LIFE FORCE OR PRANA ENERGY CHAPTER 16 THE SHINING -

Selected Gems from Ashtavakra Gita

INTRODUCTION It is true that the author had written long earlier two other books on ‘Ashtavakra Gita’, a unique practical text on Advaita philosophy - ‘The Quantum Leap into the Absolute’ (a summary of the text) and ‘Instant Self - Realisation’- both of which are available in the website. The author somehow felt that he had not done full justice to that text and his mind was not satisfied. When everyone of the nearly 300 verses of ‘Ashtavakra Gita’ is a gem of “purest ray serene”, selecting a few gems out of them and presenting them with a detailed commentary has not been an easy task. As many people have dubbed him, Ashtavakra was not a revolutionary who blazed a new trail. What all he has told in Ashtavakra Gita are also to be found in Bhagavad Gita as also a number of Upanishads like Annapurnopanishad, Adhyatmopanishad, Varahopanishad, Avadhootopanishad, Sanyasopanishad, Kaivalyopanishad, Atmaprabodopanishad, Sarvasaropanishad, Niralambopanishad, Tejobindoopanishad, Kathopanishad, 2 Selected Gems from Ashtavakra Gita Brahmabindoopanishad, Mahopanishad, Yogasikha Upanishad, Muktikopanishad, Kenopanishad and Adisankara’s Prakarana texts like Viveka Choodamani and Aparokshanubhooti. Ashtavakra puts them all in a telling way, just like a whip-lash. His language is lucid and simple. Some of the slokas are like catch-words in the burden of the song in folk-lore music. For instance his expressions like ^^fo’olk{kh lq[kh Hko** (I-5), ^^u Hk;a rL; dq=fpr~** (IV-6), ^^u â";fr u dqI;fr** (VIII-2), ^^ohrr`".k% lq[kh Hko** (X-3), ^^u^^u^^u fpUrk eqDr;s ee** (XIV-3), ^^fujis{k% lq[ka pj** (XV-4), ^^u rs o`f)uZ ok {kfr%** (XV-11), ^^fu%ladYi% lq[kh Hko** (XV-15), ^^fdeH;L;fr ckyor~**] ^^;nk ukga rnk eks{kks** (VIII-4), ^^ukga nsgks u es nsgks** (XI-6), ^^R;tSo /;kua loZ=** (XV-20) and ^^fpÙka eqDrL; jktrs** (XVII-30) are beautiful and easy to remember. -

Disability and Deafness, in the Context of Religion, Spirituality, Belief And

Miles, M. 2007-07. “Disability and Deafness, in the context of Religion, Spirituality, Belief and Morality, in Middle Eastern, South Asian and East Asian Histories and Cultures: annotated bibliography.” Internet publication URLs: http://www.independentliving.org/docs7/miles200707.html and http://www.independentliving.org/docs7/miles200707.pdf The bibliography introduces and annotates materials pertinent to disability, mental disorders and deafness, in the context of religious belief and practice in the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia. Disability and Deafness, in the context of Religion, Spirituality, Belief and Morality, in Middle Eastern, South Asian and East Asian Histories and Cultures: annotated bibliography. Original version was published in the Journal of Religion, Disability & Health (2002) vol. 6 (2/3) pp. 149-204; with a supplement in the same journal (2007) vol. 11 (2) 53-111, from Haworth Pastoral Press, http://www.HaworthPress.com. The present Version 3.00 is further revised and extended, in July 2007. Compiled and annotated by M. Miles ABSTRACT. The bibliography lists and annotates modern and historical materials in translation, sometimes with commentary, relevant to disability, mental disorders and deafness, in the context of religious belief and practice in the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia, together with secondary literature. KEYWORDS. Bibliography, disabled, deaf, blind, mental, religion, spirituality, history, law, ethics, morality, East Asia, South Asia, Middle East, Muslim, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, Buddhist, Confucian, Daoist (Taoist). CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTORY NOTES 2. MIDDLE EAST & SOUTH ASIA 3. EAST (& SOUTH EAST) ASIA 1. INTRODUCTORY NOTES The bibliography is in two parts (a few items appear in both): MIDDLE EAST & SOUTH ASIA [c. -

C O N T E N T S

03.12.2014 1 C O N T E N T S Sixteenth Series, Vol. V Third Session, 2014/1936 (Saka) No. 8, Wednesday, December 03, 2014/Agrahayana 12, 1936 (Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S OBITUARY REFERENCE 2-3 ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS *Starred Question Nos. 141 to 145 5-49 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos. 146 to 160 50-97 Unstarred Question Nos. 1611 to 1768, 98-611 1770 to 1787 and 1789 to 1840 *The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. 03.12.2014 2 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 612-616 COMMITTEE ON PRIVATE MEMBERS’ BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS 2nd Report 617 STATEMENTS BY MINISTERS (i) Incident in District-Sukma, Chhattisgarh which happened on 01.12.2014 Shri Rajnath Singh 618-621 (ii) Prime Minister's recent visits abroad Shrimati Sushma Swaraj 622-627 STATEMENT CORRECTING REPLY TO UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.622 DATED 26TH NOVEMBER, 2014 REGARDING 'DECONGESTION OF DELHI' 628-629 ELECTIONS TO COMMITTEES 630-631 (i) Advisory Council of the Delhi Development 630 Authority (ii) Council of Indian Institute of Science 630-631 Bangalore (iii) National Board for Micro, Small and 631 Medium Enterprises MOTION RE: SEVENTH REPORT OF BUSINESS 632 ADVISORY COMMITTEE 03.12.2014 3 SUBMISSION BY MEMBERS (i) Re: Issue of alleged destruction of a church in East Delhi due to fire prompting allegation of foul play by church authorities 638 (ii) Re: Alleged Misbehaviour with a woman Member of Parliament by Local District Administration during foundation stone laying ceremony for Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana in Munger, Bihar.