As the Record Spins: Materialising Connections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Re-Incarnation, Adoption and Diffusion of Retro-Technologies

David Sarponga, Email: [email protected] Shi Dongb, Email: [email protected] Gloria Appiahc,, Email: [email protected] Authors Affiliationab: Bristol Business School University of the West of England Bristol, United Kingdom Authors Affiliationc: Roehampton Business School University of Roehampton London, United Kingdom ‘Vinyl never say die’: The re-incarnation, adoption and diffusion of retro-technologies New technologies continue to shape the way music is produced, distributed and consumed. The new turn to digital streaming services like iTunes, Spotify and Pandora, in particular, means that very recent music format technologies such as cassettes and CD's have almost lost their value. Surprisingly, one 'obsolete' music format technology, Vinyl record, is making a rapid comeback. Vinyl sales around the world, in recent times, have increased year on year, and the number of music enthusiast reaching for these long-playing records (LP's) continue unabated. Drawing on the sociology of translation as an interpretive lens, we examine the momentum behind the revival of vinyl record, as a preferred music format choice for a growing number of music enthusiasts. In doing this we unpack the inarticulate and latent network of relationships between human and non-human actors that constitutively give form to the contemplative knowledge (what has become) of the resurgence of vinyl as a format of choice. We conclude by discussing how insights from the vinyl reincarnation story could help open up new possibilities for rethinking the contextual re-emergence of near-obsolete technologies, the mobilization of different actors to aid their re-diffusion and potential exploitation of value from retro-technologies. -

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value in Recorded Music

CARBON Carbon – Desktop Vinyl Lathe Recapturing Value In Recorded Music MFA Advanced Product Design Degree Project Report June 2015 Christopher Wright Canada www.cllw.co TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 - Introduction Introduction 06 The Problem With Streaming 08 The Vinyl Revival 10 The Project 12 Part 2 - Research Record Sales Statistics 16 Music Consumption Trends 18 Vinyl Pros and Cons 20 How Records Are Made 22 Vinyl Pressing Prices 24 Mastering Lathes 26 Historical Review 28 Competitive Analysis 30 Abstract Digital Record Experiments 32 Analogous Research 34 Vinyl records have re-emerged as the preferred format for music fans and artists Part 3 - Field Research alike. The problem is that producing vinyl Research Trip - Toronto 38 records is slow and expensive; this makes it Expert Interviews 40 difcult for up-and-coming artists to release User Interviews 44 their music on vinyl. What if you could Extreme User Interview 48 make your own records at home? Part 4 - Analysis Research Analysis 52 User Insights 54 User Needs Analysis 56 Personas 58 Use Environment 62 Special Thanks To: Technology Analysis 64 Product Analysis 66 Anders Smith Thomas Degn Part 5 - Strategy Warren Schierling Design Opportunity 70 George Graves & Lacquer Channel Goals & Wishes 72 Tyler Macdonald Target Market 74 My APD 2 classmates and the UID crew Inspiration & Design Principles 76 Part 6 - Design Process Initial Sketch Exploration 80 Sacrificial Concepts 82 Concept Development 84 Final Direction 94 Part 7 - Result Final Design 98 Features and Details 100 Carbon Cut App 104 Cutter-Head Details 106 Mechanical Design 108 Conclusions & Reflections 112 References 114 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 4 5 INTRODUCTION Personal Interest I have always been a music lover; I began playing in bands when I was 14, and decided in my later teenage years that I would pursue a career in music. -

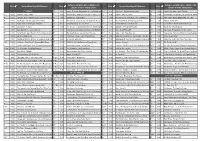

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

Vinyl, Vinyl Everywhere: the Analog Record in the Digital World

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Osborne, Richard ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4111-8980 (2018) Vinyl, Vinyl everywhere: The analog record in the digital world. In: The Routledge Companion to Media Technology and Obsolescence. Wolf, Mark J. P., ed. Routledge, pp. 200-214. ISBN 9781138216266. [Book Section] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/26044/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

La Muerte Y La Resurreción De La Portada De Discos

Received : 2014_01_09 | Accepted: 2014_02_03 37 THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF THE ALBUM COVER MUERTE Y RESURRECCIÓN DE LAS PORTADAS DE DISCOS ISMAEL LÓPEZ MEDEL [email protected] Central Connecticut State University, United States Abstract: The recording industry is facing yet another pivotal moment of rede - finition. Imagery has been one of its key elements, whether through graphic design, album art design, posters, videos and applications for digital devices. Throughout the more than hundred years of existence, music and images have shared a common space, in an ever-changing and evolving relationship. The main goal of the paper is to present how album cover design has expanded its boundaries far beyond its initial rol in the music industry, to trespass now into the textile, decoration and popular culture industries. We also aim to prove the evolution of the álbum cover and its reinterpreattion as objects of popular culture. Therefore, the paper is divided in three acts. We begin explaining the origin, evolution and significance of the discographic design from the outset of the industry. In the following act, we explain the death of the album cover due to the crisis experienced by the industry in the nineties. The final act studies the surprising comeback of the format, yet in another context, possessed with a much more symbolic function. This resurrection is part of the vinyl revival, pushed by elite consumers who are now looking for something else in music, apart from the music itself. As a result, we will witness how record covers have migrated from their original function and are now part of the realm of popular culture. -

RSD List 2020

Artist Title Label Format Format details/ Reason behind release 3 Pieces, The Iwishcan William Rogue Cat Resounds12" Full printed sleeve - black 12" vinyl remastered reissue of this rare cosmic, funked out go-go boogie bomb, full of rapping gold from Washington D.C's The 3 Pieces.Includes remixes from Dan Idjut / The Idjut Boys & LEXX Aashid Himons The Gods And I Music For Dreams /12" Fyraften Musik Aashid Himons classic 1984 Electonic/Reggae/Boogie-Funk track finally gets a well deserved re-issue.Taken from the very rare sought after album 'Kosmik Gypsy.The EP includes the original mix, a lovingly remastered Fyraften 2019 version.Also includes 'In a Figga of Speech' track from Kosmik Gypsy. Ace Of Base The Sign !K7 Records 7" picture disc """The Sign"" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). This exclusive Record Store Day version is pressed on 7"" picture disc." Acid Mothers Temple Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (Title t.b.c.)Space Age RecordingsDouble LP Pink coloured heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP Not previously released on vinyl Al Green Green Is Blues Fat Possum 12" Al Green's first record for Hi Records, celebrating it's 50th anniversary.Tip-on Jacket, 180 gram vinyl, insert with liner notes.Split green & blue vinyl Acid Mothers Temple & the Melting Paraiso U.F.O.are a Japanese psychedelic rock band, the core of which formed in 1995.The band is led by guitarist Kawabata Makoto and early in their career featured many musicians, but by 2004 the line-up had coalesced with only a few core members and frequent guest vocalists. -

RSD19 Releases PRINTABLE 27.02.19

#RSD19 Twitter: @RSDUK / Instagram: @recordstoreday / Facebook: @RSDayUK Artist Title Label Format Want 13th Floor Elevators Psychedelic Sounds Of International Artists LP Picture Disc 808 State Four States of 808 ZTT 4x12" box set A Man Called Adam Farmarama Other Records Ltd. 12" A.R. Kane New Clear Child Hidden Art Recordings Single vinyl LP Ace Frehley Spaceman (Picture Disc) Eone Entertainment 12PD Ace of Base The Sign K7 7' PICTURE DISC Acid Mothers Temple Does The Cosmic Shepherd Space Age Recordings Double LP Dream Of Electric Tapirs? Adam French The Back Foot And Rapture Virgin EMI 7" A-HA Hunting High And Low / The Rhino 1LP, Black Vinyl Early Alternate Mixes Aidan Moffat and RM What The Night Bestows US Rock Action Records LP Hubbert Air Surfing On A Rocket Warner Music France 12" Picture Disc Airto Natural Feelings Real Gone Music 12" LP Al Green The Hi Records Singles Box Fat Possum Records 7" Box Set Set Alarm, The Live '85 Twenty First Century 2LP Recording Company Albert Washington Sad And Lonely Tidal Waves Music LP Alice Clark s/t Wewantsounds Deluxe Gatefold LP ALPHA & OMEGA DUBPLATE SELECTION VOL 1 MANIA DUB LP ALPHA & OMEGA DUBPLATE SELECTION VOL 2 MANIA DUB LP Anderson .Paak Bubblin' Aftermath/12 Tone 7" Music, LLC Andrea True More, More, More Buddah Records 12" Connection Angel Pavement Socialising With Angel Morgan Blue Town LP & 7" Pavement Antoine Dobson ft Bed Intruder & Various Enjoy The Ride 7" Gregory Bros Other YouTube Hits 1 #RSD19 Twitter: @RSDUK / Instagram: @recordstoreday / Facebook: @RSDayUK Apartments, -

Keeping What Real? Vinyl Records and the Future of Independent Culture

Article Convergence: The International Journal of Research into Keeping what real? Vinyl New Media Technologies 1–14 ª The Author(s) 2019 records and the future Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions of independent culture DOI: 10.1177/1354856519835485 journals.sagepub.com/home/con Michael Palm UNC-Chapel Hill, USA Abstract The revived popularity of vinyl records in the United States provides a unique opportunity for ‘rethinking the distinction between new and old media’. With vinyl, the new/old dichotomy informs a more specific opposition between digital and analog. The vinyl record is an iconic analog artifact whose physical creation and circulation cannot be digitized. Making records involves arduous craft labor and old-school manufacturing, and the process remains essentially the same as it was in 1960. Vinyl culture and commerce today, however, abound with digital media: the majority of vinyl sales occur online, the download code is a familiar feature of new vinyl releases, and turntables outfitted with USB ports and Bluetooth are outselling traditional models. This digital disconnect between the contemporary traffic in records and their fabrication makes the vinyl revival an ideal case example for interrogating the limitations of new and old as conceptual horizons for media and for proffering alternative historical formulations and critical frameworks. Toward that end, my analysis of the revitalized vinyl economy in the United States suggests that the familiar (and always porous) distinction between corporate and independent continues to offer media studies a more salient spectrum, conceptually and empirically, than new-old or analog-digital. Drawing on ethnographic research along vinyl’s current supply chain in the United States, I argue that scholars and sup- porters of independent culture should strive to decouple the digital and the analog from the corporate, rather than from one another. -

Jeff Root Tedeschi Trucks Band Contact Karlo Takki

•Our 31st Year Proudly Promoting The Music Scene• FREE July 2016 Contact Jeff Root Karlo Takki Tedeschi Trucks Band Plus: Concert News, The Time Machine, Metronome Madness & more Metro•Scene ATWOOD’S TAVERN BLUE OCEAN MUSIC HALL 7/9- Marty Nestor & the BlackJacks 7/31- Steel Panther Cambridge, MA. Salisbury Beach, MA. 7/14- Bob Marley - Comedy (617) 864-2792 (978) 462-5888 7/15- Mike Zito & the Wheel 7/16- Joe Krown Trio w/ Walter “Wolfman” HOUSE OF BLUES Washington & Russell Batiste 7/1- Tim Gearan Band 7/1- Classic Vinyl Revival Show Tribute Bands: Cold Boston, MA. 7/21- The Devon Allman Band 7/2- Vapors Of Morphine As Ice, Danny Klein’s Full House, Ain’t That America (888) 693-BLUE 7/3- Pat & The Hats 7/3- Mighty Mystic; The Cornerstone 7/22- Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams 7/28- Boogie Stomp! 7/7- Dan Blakeslee & the Calabash Club 7/7- Lotus Land: A Tribute to Rush 7/1- Lulu Santos 7/8- Tim Gearan Band; Hayley Thompson-King 7/8- Mike Girard’s Big Swinging Thing 7/29- A Ton of Blues; The Mike Crandall Band 7/30- Jerry Garcia Birthday Bash w/ A Fine 7/2- Jesus Culture - Let It Echo Tour 7/9- Vapors Of Morphine 7/20- Yacht Rock Revival featuring Ambrosia, 7/6- The Smokers Club Presents: Cam’Ron, The Connection & The Not Fade Away Band 7/10- Laurie Geltman Band Player, Robbie Dupree, Matthew Wilder & The Underachievers, G Herbo & More 7/11- The Clock Burners feat. Eric Royer, Sean Yacht Rock Revue 7/7- Buchholz Benefit Bash featuring Thompson Staples, Jimmy Ryan & Dave Westner 7/14- Steve Augeri (Former Journey singer) Square 7/13- Greyhounds 7/15- The Machine CALVIN THEATER 7/12- K. -

Making Vinyl & the World of Physical Media Conference May 2-3, 2019 | Meistersaal | Berlin

® MAKING VINYL & THE WORLD OF PHYSICAL MEDIA CONFERENCE MAY 2-3, 2019 | MEISTERSAAL | BERLIN www.media-tech.net | www.makingvinyl.com Supported by WELCOME TO BERLIN & ‘THE BIG HALL BY THE WALL’ By Larry Jaffee and Bryan Ekus We’re so fortunate to be holding this event at the majestic Meistersaal, a one-time concert hall but more famously the same physical space that held Hansa Studios, some 200 meters from The Wall, inspiring David Bowie to write and record there in the studio “Heroes.” Bowie moved to Berlin in 1997 because it was the capital of his childhood dreams and home of Expressionist art. There he produced new music that helped further develop him into “an artist of extraordinary brilliance and originality,” writes Heroes: Bowie and Berlin author Tobias Ruther. Write academics Dominick It’s fitting that our first Making Vinyl “There’s been a Detroit-Berlin connection Bartmanski and an Woodward in their conference in Europe takes place in since the early 1990s,” explains Detroit book Vinyl: The Analogue Record in Berlin, following two U.S. events in DJ Juan Atkins in a magazine article. the Digital Age (Bloomsbury, 2015) of Detroit that also celebrated the manu- Detroit’s Cass Corridor 15 years ago Berlin: “The city is often cited as an facturing rebirth of the vinyl record. wouldn’t be a neighborhood that you important ingredient in this cultural brew They’re practically twin cities that had would want to wander around, musician/ thathad vinyl as one of its key totems, fallen in disrepair, but embraced its rich entrepreneur Jack White told the first a benchmark of quality and authentic artistic culture to lift themselves out Making Vinyl audience in November simplicity at the time when the main- of their urban decay. -

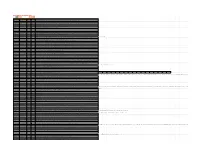

Vinyl Album Sales Exceed 1 Million in 2014

Vinyl revival Vinyl album sales exceed 1 million in 2014 Vinyl album sales in the UK exceeded the one million mark in 2014 for the first time since the 1990s Britpop era as “classic rock” fans snap up physical copies of Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd records. Whilst the music industry is adapting to a largely digital future, the attraction of a heavyweight 12” package, complete with artwork and sleeve-notes, has lured older record-buyers back to stores alongside a new generation of “hipster” collectors. There were three re-released Led Zeppelin albums and two Pink Floyd opuses, including their new release The Endless River, in the 2014 vinyl top ten. Arctic Monkeys and Jack White are the top-sellers, confirming vinyl’s renewed popularity with contemporary music fans. Vinyl is still a niche business, accounting for 2% of the UK recorded music market. Pink Floyd’s The Endless River, released in late 2014, sold just 6,000 copies, even though this was highest tally of any LP released since 1997. Artists see a vinyl release as a “badge of honour” with even One Direction releasing their new Four collection in the format. The primary purchasers are rock fans however and a new crop of bands led by Royal Blood and indie group Temples are joining the heritage acts among the year’s best-sellers. Vinyl sales UK album sales 2013 780,670 CD Digital 60.6m 32.6m 388,770 337,040 219,450 236,470 LP 0.78m Other: 0.07m 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 One vinyl shopper surveyed by the BBC at the Rough Trade East record store in East London, said: “I think it’s sort of a hipster thing. -

Global Music Report 2017 Annual State of the Industry

GLOBAL MUSIC REPORT 2017 ANNUAL STATE OF THE INDUSTRY Global top 10 recording artists of 2016 Never stop playing. GLOBAL MUSIC REPORT 2017: ANNUAL STATE OF THE INDUSTRY 3 WELCOME he IFPI Global Music Report tells a positive story of music being enjoyed by more people in more ways than ever before. At the heart of this story T are incredible artists, supported by the invest- ment and innovation from record companies and other partners that is helping them to share their music with the world. We are now in an exciting era in which streaming is making the depth and richness of every kind of music available to hundreds of millions of people, with artists Plácido Domingo connecting more directly and more quickly with their Chairman, IFPI audiences. Challenges remain, however, and the fair remunera- tion of those that create and invest in music must be a priority in this increasingly digital world. The whole community is uniting in its efforts to ensure that music is properly valued so that artists and their work can thrive. UNLOCK THE GLOBAL POWER OF NIELSEN MUSIC YOUR KEY TO THE BEST DATA-DRIVEN SOLUTIONS IN THE BUSINESS GAIN ACCESS TO MUSIC CONNECT The Industry’s Most Trusted Data & Insights with Over 20 International Charts CUSTOM RESEARCH, ANALYTICS and MORE GET THE INFORMATION YOU NEED TO GROW YOUR BUSINESS IN 2017 Contact [email protected] CONTENTS ANNUAL STATE OF THE INDUSTRY 01. Global music market 2016 figures 6 02. Introduction – Frances Moore 7 03. Global charts 8 UNLOCK 04. Global market overview 10 THE GLOBAL POWER OF 2016 figures by format and region 12 05.