On True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divine Mercy Holy Hour

Divine Mercy Holy Hour Sunday of the Twenty-ninth Week in Ordinary Time Holy Hour to the Divine Mercy Entrance Hymn: Come Holy Ghost Come Holy Ghost, Creator blest, And in our hearts take up thy rest; Come with Thy grace and heav’nly aid To fill the hearts which Thou hast made, To fill the hearts which Thou hast made. O Comfort blest, to thee we cry, Thou heav’nly Gift of God most High; Thou Font of life, and Fire of love, And sweet Anointing from above, And sweet Anointing from above. Praise be to Thee, Father and Son, And Holy Spirit, Three in One; And may the Son on us bestow The gifts that from the Spirit flow, The gifts that from the Spirit flow. 2 Exposition: (please kneel as the Celebrant approaches the tabernacle) O Salutaris Hostia O salutaris Hostia, quæ cæli pandis ostium: Bella premunt hostilia, da robur, fer auxilium. Uni trinoque Domino sit sempiterna gloria, Qui vitam sine termino nobis donet in patria. Amen. Adoration:(a few minutes of silent reflection) Scripture Reading: (please stand) (1Thessalonians 1:5-8)) For our gospel did not come to you in word alone but also in power and in the holy Spirit and with much conviction. You know what sort of people we were among you for your sake. And you became imitators of us and of the Lord, receiving the word in great affliction, with joy from the holy Spirit, so that you became a model for all believers in Macedonia and in Achaia. For from you the word of the Lord has sounded forth not only in Macedonia and Achaia, but in every place your faith in God has gone forth, so that we have no need to say anything. -

Opening of the Year of the Eucharist – June 22-23, 2019

Opening of the Year of the Eucharist – June 22-23, 2019 This Novena prayed nine days before the June 23rd start would be a great way to make immediate preparation for the Year of the Eucharist. The novena would begin on June 14. The link is here: http://www.ewtn.com/Devotionals/novena/Corpus_Christi.htm In the Masses you celebrate on June 22-23, we would suggest the following rituals to open the Year of Eucharist. 1. Gather the faithful outside the main door of the church, weather permitting. * a. Give a brief explanation of the Year of the Eucharist. Share with the faithful that this moment of processing is a symbolic way of entering the Year of the Eucharist. (sample of an explanation is attached) b. Read the decree (attached) c. Process in with a Eucharistic Hymn of your choosing from the resources you have available. d. Carry in the Year of the Eucharist banner. After the processional, have the banner carrier hang the banner on the main door of the parish church. Hooks are provided with the banner and should be attached to the door ahead of time. Additional banners can be ordered. Contact Dionne Eastmo in the Faith Formation Office. 2. Have the parishioners pray the sequence for the Feast of Corpus Christi. You could also sing it although there is no familiar melody available. (The text of the sequence is attached.) 3. Preach about the Year of the Eucharist focusing on the bishop’s desire to deepen and strengthen the faithful’s encounter with the Lord in the celebration of the Mass. -

Pope Paul VI and Ignacio Maria Calabuig: the Virgin Mary in the Liturgy and the Life of the Church Thomas A

Marian Studies Volume 65 Forty Years after ‘Marialis Cultus’: Article 8 Retrieval or Renewal? 5-23-2014 Pope Paul VI and Ignacio Maria Calabuig: The Virgin Mary in the Liturgy and the Life of the Church Thomas A. Thompson University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Thomas A. (2014) "Pope Paul VI and Ignacio Maria Calabuig: The irV gin Mary in the Liturgy and the Life of the Church," Marian Studies: Vol. 65, Article 8, Pages 179-212. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol65/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Thompson: Paul VI and Ignacio Maria Calabuig POPE PAUL VI AND IGNACIO MARIA CALABUIG: THE VIRGIN MARY IN THE LITURGY AND THE LIFE OF THE CHURCH Fr. Thomas A. Thompson, SM On this fortieth anniversary of Marialis Cultus, we wish to commemorate Paul VI and Ignacio Calabuig, both of whom made singular contributions to implementing Vatican II’s directives for the reform and strengthening of Marian devotion in the liturgy, or, as expressed at Vatican II, who collaborated “that devotion to the Virgin Mary, especially in 1 the liturgy, be generously fostered” (LG 67). Here a brief 1 Abbreviations: SC—Sacrosantum Concilium: Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy LG—Lumen Gentium: Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World MC—Marialis Cultus: Apostolic Exhortation of Paul VI Collection—Collection of Masses of the Blessed Virgin Mary CM-M (no. -

Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament & the Divine Mercy Chaplet

Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament & the Divine Mercy Chaplet Song for Exposition – O Salutaris Hostia: O saving Victim, open wide O salutaris Hostia The gate of heaven to us below, Quae caeli pandis ostium, Our foes press on from every side; Bella premunt hostilia, Your aid supply, Your strength bestow. Da robur, fer auxilium. To Your great name be endless praise, Uni trinoque Domino Immortal Godhead, One in Three; Sit sempiterna Gloria, O grant us endless length of days Qui vitam sine termino In our true native land with Thee. Nobis donet in patria. Amen. Amen. Opening Prayer (prayed together): You expired, Jesus, but the source of life gushed forth for souls, and the ocean of mercy opened up for the whole world. O Fount of Life, unfathomable Divine Mercy, envelop the whole world and empty Yourself out upon us. O Blood and Water, which gushed forth from the Heart of Jesus as a fountain of Mercy for us, I trust in You! O Blood and Water, which gushed forth from the Heart of Jesus as a fountain of Mercy for us, I trust in You! O Blood and Water, which gushed forth from the Heart of Jesus as a fountain of Mercy for us, I trust in You! The Our Father (prayed together): Our Father, Who art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy name; Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. -

The Cross of Christ Son of God Son of Man His Life Poured out for All See

The Cross Of Christ Son of God son of man His life poured out for all See His hands see His scars His love can't be denied Our God is high and lifted up Chorus It is the cross my only plea The blood He shed delivers me Our Savior's arms are open wide A love so great the cross of Christ Ev'ry debt all we owe He bears it as His own Brought to life we are free to live In Christ alone Our God is high and lifted up See the Lamb of God see the Father's love All to Jesus we owe He paid it all See the Lamb of God see the Father's love All to Jesus we owe He paid it all All to Jesus we owe He paid it all Kyrie Eleison Lord have mercy Christ have mercy Hear our cry and heal our land Let kindness lead us to repentance Bring us back again Chorus 1 For Your name is great and Your heart is grace Kyrie Eleison Over all You reign You alone can save Kyrie Eleison Lord have mercy Christ have mercy on us now Who is this God who pardons all our sin So ready to forgive You delight to show Your mercy Chorus 2 For Your name is great and Your heart is grace Kyrie Eleison Over all You reign You alone can save Kyrie Eleison Lord have mercy Christ have mercy Lord have mercy Christ have mercy on us now Lead Me To The Cross Saviour I come quiet my soul Remember redemption's hill Where Your blood was spilled For my ransom Pre-Chorus Ev’rything I once held dear I count it all as loss Chorus Lead me to the cross Where Your love poured out Bring me to my knees Lord I lay me down Rid me of myself I belong to You Oh lead me lead me to the cross You were as I tempted and -

Mass for Divine Mercy Sunday

THE SECOND SUNDAY OF EASTER 2021 OCTAVE DAY OF THE RESURRECTION OF THE LORD MASS FOR DIVINE MERCY SUNDAY Saint John XXIII Roman Catholic Church Winnipeg, Manitoba Saturday, April 10, 2021 4:00 p.m. Livestream PREPARATION FOR THE CELEBRATION Misericordes sicut Pater! Merciful like the Father THE INTRODUCTORY RITES ENTRANCE CHANT That Easter Day with Joy Was Bright CBW 392 1. That Easter day with joy was bright, The sun shone out with fairer light, Alleluia, alleluia! When to their longing eyes restored, The glad apostles saw their Lord. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! 2 2. His risen flesh with radiance glowed; His wounded hands and feet he showed; Alleluia, alleluia! Those scars their solemn witness gave That Christ was risen from the grave. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! 3. O Jesus, in your gentleness, With constant love our hearts possess; Alleluia, alleluia! To you our lips will ever raise The tribute of our grateful praise. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! 4. O Lord of all, with us abide In this our joyful Eastertide; Alleluia, alleluia! From ev'ry weapon death can wield Your own redeemed for ever shield. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! 5. All praise to you, O risen Lord, Now by both heav’n and earth adored; Alleluia, alleluia! To God the Father equal praise, And Spirit blest our songs we raise. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! Text: Claro paschali gaudio, Latin 5th C., tr. by John Mason Neale, 1818-1866; alt. Tune: LASST UNS ERFREUEN, LM with alleluias, Geistliche Kirchengesange, 1623 SIGN OF THE CROSS GREETING The people reply: And with your spirit. -

Marian Studies Volume 65 Forty Years After ‘Marialis Cultus’: Article 4 Retrieval Or Renewal?

Marian Studies Volume 65 Forty Years after ‘Marialis Cultus’: Article 4 Retrieval or Renewal? 5-23-2014 Marian 'Spiritual Attitude' and Marian Piety Patricia A. Sullivan St. Anselm College Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Patricia A. (2014) "Marian 'Spiritual Attitude' and Marian Piety," Marian Studies: Vol. 65, Article 4, Pages 43-78. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol65/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Sullivan: 'Spiritual Attitude' MARIAN ‘SPIRITUAL ATTITUDE’ AND MARIAN PIETY Patricia A. Sullivan, PhD As Marialis Cultus 1 would seem to assert, ideally Marian spirituality and Marian devotion are united, yet they are distinct. Pope Paul VI wrote of a Marian “spiritual attitude”2 that Mary is “a most excellent exemplar of the Church in the order of faith, charity and perfect union with Christ, that is, of that interior disposition with which the Church, the beloved spouse, closely associated with her Lord, invokes Christ and through Him worships the eternal 1 Paul VI, Pope, Marialis Cultus (MC) (2 February 1974), available from the Vatican, at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_p- vi_exh_19740202_marialis-cultus_en.html (accessed 20 October 2013). 2 MC, 16. 43 Published by eCommons, 2014 1 Marian Studies, Vol. -

May 2021 Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament

MAY MARIAN DEVOTION MAY 2021 EXPOSITION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT HYMN O SALUTARIS HOSTIA O salutaris Hostia, O saving Victim, opening wide Quæ cæli pandis ostium: The gate of Heaven to us below; Bella premunt hostilia, Our foes press hard on every side; Da robur, fer auxilium. Thine aid supply; thy strength bestow. Uni trinoque Domino To thy great name be endless praise, Sit sempiterna gloria, Immortal Godhead, One in Three. Qui vitam sine termino Oh, grant us endless length of days, Nobis donet in patria. In our true native land with thee. Amen. Amen. OPENING PRAYER SILENT ADORATION RECITATION OF THE ROSARY Apostles Creed - I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting. Amen. Our Father - Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. -

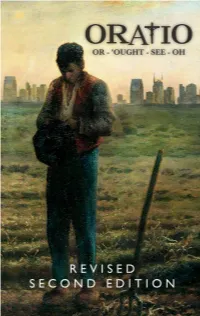

Oratio-Sample.Pdf

REVISED SECOND EDITION RHYTHMS OF PRAYER FROM THE HEART OF THE CHURCH DILLON E. BARKER JIMMY MITCHELL EDITORS ORATIO (REVISED SECOND EDITION) © 2017 Dillon E. Barker & Jimmy Mitchell. First edition © 2011. Second edition © 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-692-89224-4 Published by Mysterium LLC Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.A. LoveGoodCulture.com NIHIL OBSTAT: Rev. Jayd D. Neely Censor Librorum IMPRIMATUR: Most Rev. David R. Choby Bishop of Nashville May 9, 2017 For bulk orders or group rates, email [email protected]. Special thanks to Jacob Green and David Lee for their contributions to this edition. Excerpts taken from Handbook of Prayers (6th American edition) Edited by the Rev. James Socias © 2007, the Rev. James Socias Psalms reprinted from The Psalms: A New Translation © 1963, The Grail, England, GIA Publications, Inc., exclusive North American agent, www.giamusic.com. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the Revised Standard Version Bible, Second Catholic Edition © 2000 & 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 2010, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Rites of the Catholic Church © 1990, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Book of Blessings © 1988, 1990, USCCB & ICEL. All rights reserved. All ritual texts of the Catholic Church not already mentioned are © USCCB & ICEL. Cover art & design by Adam Lindenau adapted from “The Angelus” by Jean-François Millet, 1857 The Tradition of the Church proposes to the faithful certain rhythms of praying intended to nourish continual prayer. Some are daily, such as morning and evening prayer, grace before and after meals, the Liturgy of the Hours. -

Well-Known Catholic Prayers — Page 2 HAIL, HOLY “Whoever Has God Wants for Nothing

Wel l-Known Catholic Pr ayer s For your songs and proverbs and parables, and for your interpretations, the countries marveled at you. ~ Sirach 47:17 SIGN OF THE CROSS In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. OUR FATHER Our Father, who art in Heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy Kingdom come; DAVID CHARLES PHOTOGRAPHY thy will be done on earth as it is in Heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen. HAIL MARY A rosary from Ireland Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. GLORIA Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Glory to God in the highest, Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, and peace to his people on earth. now and at the hour of our death. Amen. Lord God, Heavenly King, Almighty God and Father, CONFITEOR we worship you, we give you thanks, I confess to almighty God, we praise you for your glory. and to you, my brothers and sisters, Lord Jesus Christ, only Son of the Father, that I have sinned through my own fault, Lord God, Lamb of God, you take away the sins They strike their breast: of the world, have mercy on us. in my thoughts and in my words, You are seated at the right hand of the Father, in what I have done receive our prayer. -

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Walsingham

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Walsingham The Personal Ordinariate of The Chair of Saint Peter Under Protection of Our Lady of Walsingham Bishop Steven J. Lopes Father Charles A. Hough IV – Rector & Pastor Deacon Justin Fletcher – Transitional Deacon Deacon James Barnett, Deacon Mark Baker, Deacon Mark Stockstill – Pastoral Assistants + Solemnity of Christ the King + 25 November AD 2018 + The Cathedral of Our Lady of Walsingham 7809 Shadyvilla Lane + Houston Texas 77055 713-683-9407 + Fax: 713-683-1518 + olwcatholic.org Parish Secretary: Catherine Heath [email protected] Business Manager/Director of Facilities: Deacon Mark Stockstill Director of Sacramental Life: Deacon James Barnett Director of Education: Sr. Thomas Aquinas, OP Director of CCD / Holy House Academy: Catalina Brand Director of Office of Liturgy/Co-Director of Altar Guild: Carolyn Barnett Associate Director of Office of Liturgy/Director of Development: Rebecca Hill Director of Music/Organist: Edmund Murray Associate Director of Music: Chalon Murray Director of Events/Co-Director of Altar Guild: Ana Newton Director of RCIA: Deacon Mark Baker Director of Youth Ministry: Joshua Korf Director of Family Life Ministries: Mary Halbleib Safe Environment Coordinator: Chalon Murray Call the Parish Office if you wish to. + become a Registered Member of Our Lady of Walsingham + explore the possibility of becoming Roman Catholic + schedule a Wedding or a Baptism + talk about the Annulment process + schedule a Confession by appointment November Prayer Intentions of the Holy Father, Pope Francis That consecrated religious men and women may bestir themselves, and be present among the poor, the marginalized, and those who have no voice. Welcome to Our Visitors Thank you for sharing in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass with us today. -

Holy Thursday from Home - Page 2 Extract from Roman Catholic Daily Missal

D I O C E S E O F M A D I S O N Holy Week at Home An aid for families seeking to celebrate holy week fruitfully at home CONTENTS How to pray the TV Mass Holy Thursday from home - page 2 Extract from Roman Catholic Daily Missal Lenten penance - page 3 The Mass today specially commemorates the Institution of the Blessed Eucharist at the Last Supper, and the Ordination of the Apostles, and is, therefore, a Mass Family prayers - page 3 of joy and thanksgiving. Hence the Church lays aside for the moment the penitential violet, and assumes festive white vestments; the altar is decorated; the Gloria is said. During the Gloria the bells are rung, and from that time until Hymns - page 4 the Easter Vigil they remain silent. Meditation - page 5 After the evening Mass the Altar is stripped in order to show that the holy Sacrifice is interrupted and will not be offered again until Holy Saturday is Bible study - page 6 ending. Family activities - page 6 Unite yourself spiritually to the mass by standing, kneeling, sitting, and responding as if you were actually present. List of Online and Televised Masses Viewable in the Diocese of Madison Act of Spiritual Communion My Jesus, I believe that You are present in the Most Holy Sacrament. I love You above all things, and I desire to receive You into my soul. Since I cannot at this moment receive You sacramentally, come at least spiritually into my heart. I embrace You as if You were already there and unite myself wholly to You.