The Mirror Neuron System and Empathy: a Meta-Analysis 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 Tuth 11:00 - 12:20 Pm CSB 005

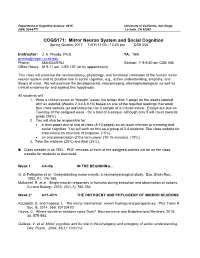

Department of Cognitive Science 0515 University of California, San Diego (858) 534-6771 La Jolla, CA 92093 COGS171: Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 TuTH 11:00 - 12:20 pm CSB 005 Instructor: J. A. Pineda, Ph.D. TA: TBN [email protected] Phone: 858-534-9754 SeCtion: F 9-9:50 am CSB 005 OffiCe Hours: M 9-11 am, CSB 107 (or by appointment) This class will examine the neuroanatomy, physiology, and funCtional Correlates of the human mirror neuron system and its putative role in soCial Cognition, e.g., aCtion understanding, empathy, and theory of mind. We will examine the developmental, neuroimaging, electrophysiologiCal, as well as clinical evidence for and against this hypothesis. All students will: 1. Write a CritiCal review or “thought” essay (no longer than 1 page) on the weeks labeled with an asterisk (Weeks 2,3,4,6,8,10) based on one of the required readings that week. See Class website (or ask instruCtor) for a sample of a CritiCal review. Essays are due on Tuesday of the assigned week - for a total of 6 essays, although only 5 will count towards grade (25%). 2. You will also be responsible for: • a term paper due at end of class (8-10 pages) on an issue relevant to mirroring and social cognition. You will work on this as a group of 3-4 students. See Class website for instruCtions on structure of proposal. (15%) • an oral presentation of the term paper (10-15 minutes). (10%) 3. Take the midterm (25%) and final (25%). -

Biological Motion Perception in Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Meta-Analysis Greta Krasimirova Todorova1* , Rosalind Elizabeth Mcbean Hatton2 and Frank Earl Pollick1

Todorova et al. Molecular Autism (2019) 10:49 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0299-8 RESEARCH Open Access Biological motion perception in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis Greta Krasimirova Todorova1* , Rosalind Elizabeth Mcbean Hatton2 and Frank Earl Pollick1 Abstract Background: Biological motion, namely the movement of others, conveys information that allows the identification of affective states and intentions. This makes it an important avenue of research in autism spectrum disorder where social functioning is one of the main areas of difficulty. We aimed to create a quantitative summary of previous findings and investigate potential factors, which could explain the variable results found in the literature investigating biological motion perception in autism. Methods: A search from five electronic databases yielded 52 papers eligible for a quantitative summarisation, including behavioural, eye-tracking, electroencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Results: Using a three-level random effects meta-analytic approach, we found that individuals with autism generally showed decreased performance in perception and interpretation of biological motion. Results additionally suggest decreased performance when higher order information, such as emotion, is required. Moreover, with the increase of age, the difference between autistic and neurotypical individuals decreases, with children showing the largest effect size overall. Conclusion: We highlight the need for methodological standards and clear distinctions -

The Mirror Neuron System: How Cognitive Functions Emerge from Motor Organization Leonardo Fogassi

The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization Leonardo Fogassi To cite this version: Leonardo Fogassi. The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor or- ganization. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Elsevier, 2010, 77 (1), pp.66. 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009. hal-00921186 HAL Id: hal-00921186 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00921186 Submitted on 20 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Title: The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization Author: Leonardo Fogassi PII: S0167-2681(10)00177-0 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009 Reference: JEBO 2604 To appear in: Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization Received date: 26-7-2009 Revised date: 19-4-2010 Accepted date: 20-4-2010 Please cite this article as: Fogassi, L., The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (2010), doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. -

University of Groningen Empathic Accuracy and Oxytocin After

University of Groningen Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression Hogenelst, Koen; Schoevers, Robert A.; Kema, Ido; Sweep, Fred C G J; aan het Rot, Marije Published in: Psychopharmacology DOI: 10.1007/s00213-015-4093-9 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Hogenelst, K., Schoevers, R. A., Kema, I. P., Sweep, F. C. G. J., & Aan Het Rot, M. (2016). Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression. Psychopharmacology, 233(1), 111-120 . DOI: 10.1007/s00213-015-4093-9 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 11-02-2018 Psychopharmacology (2016) 233:111–120 DOI 10.1007/s00213-015-4093-9 ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression Koen Hogenelst1,2 & Robert A. -

Empathy, Mirror Neurons and SYNC

Mind Soc (2016) 15:1–25 DOI 10.1007/s11299-014-0160-x Empathy, mirror neurons and SYNC Ryszard Praszkier Received: 5 March 2014 / Accepted: 25 November 2014 / Published online: 14 December 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article explains how people synchronize their thoughts through empathetic relationships and points out the elementary neuronal mechanisms orchestrating this process. The many dimensions of empathy are discussed, as is the manner by which empathy affects health and disorders. A case study of teaching children empathy, with positive results, is presented. Mirror neurons, the recently discovered mechanism underlying empathy, are characterized, followed by a theory of brain-to-brain coupling. This neuro-tuning, seen as a kind of synchronization (SYNC) between brains and between individuals, takes various forms, including frequency aspects of language use and the understanding that develops regardless of the difference in spoken tongues. Going beyond individual- to-individual empathy and SYNC, the article explores the phenomenon of syn- chronization in groups and points out how synchronization increases group cooperation and performance. Keywords Empathy Á Mirror neurons Á Synchronization Á Social SYNC Á Embodied simulation Á Neuro-synchronization 1 Introduction We sometimes feel as if we just resonate with something or someone, and this feeling seems far beyond mere intellectual cognition. It happens in various situations, for example while watching a movie or connecting with people or groups. What is the mechanism of this ‘‘resonance’’? Let’s take the example of watching and feeling a film, as movies can affect us deeply, far more than we might realize at the time. -

The Neural Components of Empathy: Predicting Daily Prosocial Behavior

doi:10.1093/scan/nss088 SCAN (2014) 9,39^ 47 The neural components of empathy: Predicting daily prosocial behavior Sylvia A. Morelli, Lian T. Rameson, and Matthew D. Lieberman Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563 Previous neuroimaging studies on empathy have not clearly identified neural systems that support the three components of empathy: affective con- gruence, perspective-taking, and prosocial motivation. These limitations stem from a focus on a single emotion per study, minimal variation in amount of social context provided, and lack of prosocial motivation assessment. In the current investigation, 32 participants completed a functional magnetic resonance imaging session assessing empathic responses to individuals experiencing painful, anxious, and happy events that varied in valence and amount of social context provided. They also completed a 14-day experience sampling survey that assessed real-world helping behaviors. The results demonstrate that empathy for positive and negative emotions selectively activates regions associated with positive and negative affect, respectively. Downloaded from In addition, the mirror system was more active during empathy for context-independent events (pain), whereas the mentalizing system was more active during empathy for context-dependent events (anxiety, happiness). Finally, the septal area, previously linked to prosocial motivation, was the only region that was commonly activated across empathy for pain, anxiety, and happiness. Septal activity during each of these empathic experiences was predictive of daily helping. These findings suggest that empathy has multiple input pathways, produces affect-congruent activations, and results in septally mediated prosocial motivation. http://scan.oxfordjournals.org/ Keywords: empathy; prosocial behavior; septal area INTRODUCTION neuroimaging studies of empathy, 30 focused on empathy for pain Human beings are intensely social creatures who have a need to belong (Fan et al., 2011). -

Mirror Neurons and Their Reflections

Open Access Library Journal Mirror Neurons and Their Reflections Mehmet Tugrul Cabioglu1, Sevgin Ozlem Iseri2 1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Baskent University, Ankara, Turkey 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey Received 23 October 2015; accepted 7 November 2015; published 12 November 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Human mirror neuron system is believed to provide the basic mechanism for social cognition. Mirror neurons were first discovered in 1990s in the premotor area (F5) of macaque monkeys. Besides the premotor area, mirror neuron systems, having different functions depending on their locations, are found in various cortical areas. In addition, the importance of cingulate cortex in mother-infant relationship is clearly emphasized in the literature. Functional magnetic resonance imaging, electroencephalography, transcortical magnetic stimulation are the modalities used to evaluate the, activity of mirror neurons; for instance, mu wave suppression in electroencephalo- graphy recordings is considered as an evidence of mirror neuron activity. Mirror neurons have very important functions such as language processing, comprehension, learning, social interaction and empathy. For example, autistic individuals have less mirror neuron activity; therefore, it is thought that they have less ability of empathy. Responses of mirror neurons to object-directed and non-object directed actions are different and non-object directed action is required for the activa- tion of mirror neurons. Previous researchers find significantly more suppression during the ob- servation of object-directed movements as compared to mimed actions. -

The Neural Bases of Empathic Accuracy

The neural bases of empathic accuracy Jamil Zaki1, Jochen Weber, Niall Bolger, and Kevin Ochsner Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027 Edited by Michael I. Posner, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, and approved May 14, 2009 (received for review March 12, 2009) Theories of empathy suggest that an accurate understanding of remains unknown, because extant methods are unable to address another’s emotions should depend on affective, motor, and/or this question. To explore the neural bases of accurate interper- higher cognitive brain regions, but until recently no experimental sonal understanding, a method would need to indicate that method has been available to directly test these possibilities. Here, activation of a neural system predicts a match between perceiv- we present a functional imaging paradigm that allowed us to ers’ beliefs about targets’ internal states and the states targets address this issue. We found that empathically accurate, as com- report themselves to be experiencing (21). pared with inaccurate, judgments depended on (i) structures Instead, extant studies have probed neural activity while within the human mirror neuron system thought to be involved in perceivers passively view or experience actions and sensory shared sensorimotor representations, and (ii) regions implicated in states or make judgments about fictional targets whose internal mental state attribution, the superior temporal sulcus and medial states are implied in pictures or fictional vignettes. In either case, prefrontal cortex. These data demostrate that activity in these 2 comparisons between perceiver judgments and what targets sets of brain regions tracks with the accuracy of attributions made actually experienced cannot be made. -

Theory of Mind and Empathy As Multidimensional Constructs Neurological Foundations

Top Lang Disorders Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 282–295 Copyright c 2014 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Theory of Mind and Empathy as Multidimensional Constructs Neurological Foundations Jonathan Dvash and Simone G. Shamay-Tsoory Empathy describes an individual’s ability to understand and feel the other. In this article, we review recent theoretical approaches to the study of empathy. Recent evidence supports 2 possible empathy systems: an emotional system and a cognitive system. These processes are served by separate, albeit interacting, brain networks. When a cognitive empathic response is generated, the theory of mind (ToM) network (i.e., medial prefrontal cortex, superior temporal sulcus, temporal poles) and the affective ToM network (mainly involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) are typically involved. In contrast, the emotional empathic response is driven mainly by simulation and involves regions that mediate emotional experiences (i.e., amygdala, insula). A decreased empathic response may be due to deficits in mentalizing (cognitive ToM, affective ToM) or in simulation processing (emotional empathy), with these deficits mediated by different neural systems. It is proposed that a balanced activation of these 2 networks is required for appropriate social behavior. Key words: emotion, empathy, inferior frontal gyrus, mirror neurons, simulation, theory of mind, ventromedial prefrontal cortex NE of the core functions of individu- have provided evidence of the multidimen- O als living within a society is the attribu- sional nature of ToM. In this article, we review tion of mental states to others. This function, main approaches to the study of the neural ba- known as theory of mind (ToM) or “mental- sis of ToM and empathy (including tasks used izing” (Frith, 1999), enables an individual to to elicit them), describe the neurological un- understand or predict another person’s be- derpinnings for the multidimensional nature havior and to react accordingly. -

Social Cognition and the Mirror Neuron System of the Brain

Motivating Questions Social Cognition and the Mirror How do our brains perceive the Neuron System of the Brain mental states of others despite their inaccessibility? How do we understand the actions, emotions and the intentions of others? Rationally? Intuitively? Jaime A. Pineda, Ph.D. Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory How do we understand first- COGS1 class and third-person experiences? Classic Explanation A Different Perspective Theory-Theory (argument from analogy; disembodied Simulation Theory knowledge; visual hypothesis) (Direct-matching hypothesis; embodied knowledge) Map visual information onto Involves striate, extrastriate, motor representations of the inferotemporal lobe and same action superior temporal sulcus, among others Mirroring systems bridges between perception and action that allow for simulation Mirror neurons EEG Mu rhythms A Different Perspective The Mirror Neuron System Simulation Theory (Direct-matching hypothesis; embodied knowledge) Map visual information onto motor representations of the same action Mirroring systems bridges between perception and action that allow for simulation Mirror neurons EEG Mu rhythms Iacoboni and Dapretto, Nature Reviews, 2006,7:942-951 1 Biological Motion Biological Motion Perception: Monkeys Visual system's ability to Gender recover object information Activity engaged in Perret and colleagues from sparse input Emotional state (1989; 1990; 1994) Cells in superior temporal polysensory area (STPa) of the macaque temporal cortex appear sensitive to biological motion Oram & Perrett, J. Cog. Neurosci., 1994, 6(2), 99-116 Biological Motion Perception: Humans Brain Circuit for Social Perception (SP) An area in the superior • SP is processing of temporal sulcus (STS) in information that results in humans responds to the accurate analysis of biological motion the intentions of others • STS involved in the Other areas do as well, processing of a variety of including frontal cortex, social signals SMA, insula, thalamus, amygdala Grossman et al. -

University of London Thesis

2 8 0 9 2 8 8 7 1 4 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree plnib Year 2au^7 Name of Author COPYRIGHT *----------------- This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. -

Ostracism-Induced Physical Pain Sensitization in Real-Life Relationships

Ostracism and Pain Sensitivity 1 Do You Really Want to Hurt Me? Ostracism-Induced Physical Pain Sensitization in Real-Life Relationships Annelise K. Dickinson Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania Ostracism and Pain Sensitivity 2 Abstract In humans, social and physical pain are believed to arise from common neural networks, an evolutionarily advantageous system for motivating prosocial behavior. As such, the hypothesis that social insult can sensitize physical pain perception was investigated in the context of real- life relationships. The social value ascribed to the source of virtual ostracism, the closeness of the relationship, and individual personality characteristics were expected to modulate the impact of social rejection upon physical pain reports. Romantic partners, friends, and strangers were all led to believe that their partners were excluding them from an online ball-tossing game, and pain sensitivity changes from baseline were assessed following this manipulation. Results indicated that ostracism by a relationship partner leads to an increase in cold pain tolerance, that romantic partners report more cold pain unpleasantness than friends following social rejection, and that trait sensitivity to social insult predicts physical pain sensitivity in general. The findings suggest that within the context of real-life relationships, the social rejection as an agent of influence upon pain behavior may not operate as cleanly as previously believed, and that further research in this area is definitely warranted. Results are interpreted with respect to several theories of social and physical pain behaviors, and suggestions for future studies are highlighted. Ostracism and Pain Sensitivity 3 Introduction Pain What is Pain? The mind is responsible for keeping itself and the body safe from harm.