Dermochelys Blainville, 1816 DERMO Dermo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

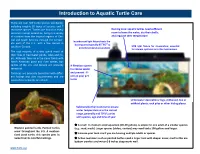

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

N.C. Turtles Checklist

Checklist of Turtles Historically Encountered In Coastal North Carolina by John Hairr, Keith Rittmaster and Ben Wunderly North Carolina Maritime Museums Compiled June 1, 2016 Suborder Family Common Name Scientific Name Conservation Status Testudines Cheloniidae loggerhead Caretta caretta Threatened green turtle Chelonia mydas Threatened hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata Endangered Kemp’s ridley Lepidochelys kempii Endangered Dermochelyidae leatherback Dermochelys coriacea Endangered Chelydridae common snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina Emydidae eastern painted turtle Chrysemys picta spotted turtle Clemmys guttata eastern chicken turtle Deirochelys reticularia diamondback terrapin Malaclemys terrapin Special concern river cooter Pseudemys concinna redbelly turtle Pseudemys rubriventris eastern box turtle Terrapene carolina yellowbelly slider Trachemys scripta Kinosternidae striped mud turtle Kinosternon baurii eastern mud turtle Kinosternon subrubrum common musk turtle Sternotherus odoratus Trionychidae spiny softshell Apalone spinifera Special concern NOTE: This checklist was compiled and updated from several sources, both in the scientific and popular literature. For scientific names, we have relied on: Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [van Dijk, P.P., Iverson, J.B., Rhodin, A.G.J., Shaffer, H.B., and Bour, R.]. 2014. Turtles of the world, 7th edition: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution with maps, and conservation status. In: Rhodin, A.G.J., Pritchard, P.C.H., van Dijk, P.P., Saumure, R.A., Buhlmann, K.A., Iverson, J.B., and Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.). Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs 5(7):000.329–479, doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v7.2014; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. -

A Phylogenomic Analysis of Turtles ⇑ Nicholas G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83 (2015) 250–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A phylogenomic analysis of turtles ⇑ Nicholas G. Crawford a,b,1, James F. Parham c, ,1, Anna B. Sellas a, Brant C. Faircloth d, Travis C. Glenn e, Theodore J. Papenfuss f, James B. Henderson a, Madison H. Hansen a,g, W. Brian Simison a a Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Department of Environmental Health Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA f Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA g Mathematical and Computational Biology Department, Harvey Mudd College, 301 Platt Boulevard, Claremont, CA 9171, USA article info abstract Article history: Molecular analyses of turtle relationships have overturned prevailing morphological hypotheses and Received 11 July 2014 prompted the development of a new taxonomy. Here we provide the first genome-scale analysis of turtle Revised 16 October 2014 phylogeny. We sequenced 2381 ultraconserved element (UCE) loci representing a total of 1,718,154 bp of Accepted 28 October 2014 aligned sequence. Our sampling includes 32 turtle taxa representing all 14 recognized turtle families and Available online 4 November 2014 an additional six outgroups. Maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and species tree methods produce a single resolved phylogeny. -

A Case of Inversion and Duplication Involving Constitutive Heterochromatin

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 36, 3, 353-356 (2013) Copyright © 2013, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil www.sbg.org.br Short Communication Cytogenetic comparison of Podocnemis expansa and Podocnemis unifilis: A case of inversion and duplication involving constitutive heterochromatin Ricardo José Gunski1, Isabel Souza Cunha2, Tiago Marafiga Degrandi1, Mario Ledesma3 and Analía Del Valle Garnero1 1Universidade Federal do Pampa, Campus São Gabriel, São Gabriel, RS, Brazil. 2Secretaria Municipal de Meio Ambiente e Turismo, São Desidério, BA, Brazil. 3Parque Ecológico “El Puma”, Candelaria, Argentina. Abstract Podocnemis expansa and P. unifilis present 2n = 28 chromosomes, a diploid number similar to those observed in other species of the genus. The aim of this study was to characterize these two species using conventional staining and differential CBG-, GTG and Ag-NOR banding. We analyzed specimens of P. expansa and P. unifilis from the state of Tocantins (Brazil), in which we found a 2n = 28 and karyotypes differing in the morphology of the 13th pair, which was submetacentric in P. expansa and telocentric in P. unifilis. The CBG-banding patterns revealed a heterochromatic block in the short arm of pair 13 of P. expansa and an interstitial one in pair 13 of P. unifilis, suggest- ing a pericentric inversion. Pair 14 of P. unifilis showed an insterstitial band in the long arm that was absent in P. expansa, suggesting a duplication in this region. Ag-NORs were observed in the first chromosome pair of both spe- cies and was associated to a secondary constriction and heterochromatic blocks. Keywords: chromosome banding, Ag-NORs, karyotype, chelonids. -

Turtles, All Marine Turtles, Have Been Documented Within the State’S Borders

Turtle Only four species of turtles, all marine turtles, have been documented within the state’s borders. Terrestrial and freshwater aquatic species of turtles do not occur in Alaska. Marine turtles are occasional visitors to Alaska’s Gulf Coast waters and are considered a natural part of the state’s marine ecosystem. Between 1960 and 2007 there were 19 reports of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the world’s largest turtle. There have been 15 reports of Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). The other two are extremely rare, there have been three reports of Olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) and two reports of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Currently, all four species are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Prior to 1993, Alaska marine turtle sightings were mostly of live leatherback sea turtles; since then most observations have been of green sea turtle carcasses. At present, it is not possible to determine if this change is related to changes in oceanographic conditions, perhaps as the result of global warming, or to changes in the overall population size and distribution of these species. General description: Marine turtles are large, tropical/subtropical, thoroughly aquatic reptiles whose forelimbs or flippers are specially modified for swimming and are considerably larger than their hind limbs. Movements on land are awkward. Except for occasional basking by both sexes and egg-laying by females, turtles rarely come ashore. Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Although their age is often exaggerated, they probably live 50 to 100 years. Of the five recognized species of marine turtles, four (including the green sea turtle) belong to the family Cheloniidae. -

Harvested Testudines

Testudines HARVESTED – Is the species collected by humans? Species Common Name Harvested Cheloniidae sea turtles Caretta c. caretta Atlantic loggerhead Unk Chelonia m. mydas Atlantic green turtle YF Economically Chelonia mydas is the most important reptile in the world. Its flesh and its eggs serve as an important source of protein in many third-world nations where protein is scarce (Ernst et al. 1994) Eretmochelys i. imbricata Atlantic hawksbill YF hawksbill flesh and eggs are eaten in many parts of its range (Ernst et al. 1994); YC throughout its range it is hunted for the plates of its shells (Ernst et al. 1994) Lepidochelys kempii Kemp’s ridley or Atlantic ridley YF egg poaching caused the initial decline [in population size] (Delikat 1981; Hall et al. 1983; Lutz and Lutcavage 1989; Ross et al. 1989; Thompson 1989; National Research Council 1990; Caillouet et al. 1991) Dermochelyidae leatherback sea turtles Dermochelys c. coriacea Atlantic leatherback YF gathering the eggs for both commerce and personal consumption (Ernst et al. 1994) Chelydridae snapping turtles Chelydra s. serpentina eastern snapping turtle YF the flesh of the snapping turtle is tasty and eaten throughout the range…fresh eggs are edible if fried (Ernst et al. 1994) Emydidae pond turtles Chrysemys p. picta eastern painted turtle Unk Chrysemys p. marginata midland painted turtle Unk Clemmys guttata spotted turtle YP (Lovich and Jaworski 1988; Lovich 1989; J. Harding, pers. comm.) Clemmys insculpta wood turtle YP (Ernst et al. 1994) Clemmys muhlenbergii bog turtle YP (D.E. Collins 1990); YF eaten by people (Ernst et al. 1994) Deirochelys r. -

Reproductive Physiology of Nesting Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys Coriacea) at Las Baulas National Park, Costa Rica

Chelolliall COllserwuioll (lnd Biology, 1996,2(2):230- 236 © 1996 by Chelonian Research Foundation Reproductive Physiology of Nesting Leatherback Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) at Las Baulas National Park, Costa Rica i 2 3 4 DAVID C. ROSTAL , FRANK V. PALADIN0 , RHONDA M. PATTERSON , AND JAMES R. SPOTILA I Department of Biology, Georgia Southern Uni versity, Statesboro, Georgia 30460 USA [Fax: 912-681-0845; E-mail: [email protected]}; 2Department of Biology, Indiana-Purdue University, Fort Wayne, Indiana 46805 USA ; 3Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843 USA ; 4Department o{Bioscience and Biotechnology, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 USA ABSTRACT. - The reproductive physiology of nesting leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) was studied at Playa Grande, Costa Rica, from 1992 to 1994 during November, December, and January. Ultrasonography indicated that 82 % of nesting females had mature preovulatory ovaries in November, 40 % in December, and 23 % in January. Mean follicular diameter was 3.33 ±0.02 cm and did not vary significantly through the nesting season. Plasma testosterone and estradiol levels measured by radioimmunoassay correlated strongly with reproductive condition. No correlation, however, was observed between reproductive condition and plasma progesterone levels. Testoster one declined from 2245 ± 280 pglml at the beginning of the nesting cycle to 318 ± 89 pglml at the end of the nesting cycle. Estradiol declined in a similar manner. Plasma calcium levels were constant throughout the nesting cycle. Vitellogenesis appeared complete prior to the arrival of the female at the nesting beach. Dermochelys coriacea is a seasonal nester displaying unique variations (e.g., 9 to 10 day internesting interval, yolkless eggs) on the basic chelonian pattern. -

The Latest Record of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys Coriacea

16 Coll. and Res. (2003) 16: 13-16 Coll. and Res. (2003) 16: 17-26 17 claw ending as knob; empodium divided, 5 rayed. without a short line on each side, admedian lines The Latest Record of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys with a semicircular line extending to lateral sides, Opisthosoma : dorsum with median ridge shorter and the 5-rayed empodium. coriacea) from Eastern Taiwan than submedian ridges, dorsally with about 51 rings, ventrally with about 53 microtuberculate Chun-Hsiang Chang1,2*, Chern-Mei Jang3, and Yen-Nien Cheng2 REFERENCES rings; 1st 3 dorsal annuli 9 long; lateral setae (c2) 10 long, Lt-Lt 44 apart, Lt\Vt1 38, Lt-Vt1 25; 1st 1Department of Biology, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK Keifer, H.H. 1977. Eriophyid studies C-13. ARS- ventral setae (d) 17 long, Vt1-Vt1 19 apart, 2Department of Geology, National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan 404 R.O.C. USDA, Washington, DC. 24pp. Vt1\Vt2 28, Vt1-Vt2 25; 2nd ventral setae (e) 17 3 Keifer, H.H. 1978. Eriophyid studies C-15. ARS- Department of Collection Management, National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung Taiwan 404 long, Vt2-Vt2 10 apart, Vt2\Vt3 40, Vt2-Vt3 38; USDA, Washington, DC. 24pp. R.O.C. 3rd ventral setae (f) 14 long, Vt3-Vt3 16 apart; Huang, K.W. 1999. The species and geographic accessory setae (h1) present. variation of eriophyoid mites on Yushania Coverflap: 19 wide, 12 long, with about 9 niitakayamensis of Taiwan. Proc. Symp. In (Received June 30, 2003; Accepted September 16, 2003) longitudinal ridges, genital setae (3a) 6 long, Gt- Insect Systematics and Evolution. -

Sea Turtles : the Importance of Sea Turtles to Marine Ecosystems

PHOTO TIM CALVER WHY HEALTHY OCEANS NEED SEA TURTLES : THE IMPORTANCE OF SEA TURTLES TO MARINE ECOSYSTEMS Wilson, E.G., Miller, K.L., Allison, D. and Magliocca, M. oceana.org/seaturtles S E L T R U T Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Karen Bjorndal for her review of this report. We would also like to thank The Streisand Foundation for their support of Oceana’s work to save sea turtles. PHOTO MICHAEL STUBBLEFIELD OCEANA | Protecting the World’s Oceans TABLE OF CONTENTS WHY HEALTHY OCEANS NEED SEA TURTLES 3 Executive Summary 4 U.S. Sea Turtles 5 Importance of Sea Turtles to Healthy Oceans 6 Maintaining Habitat Importance of Green Sea Turtles on Seagrass Beds Impact of Hawksbill Sea Turtles on Coral Reefs Benefit of Sea Turtles to Beach Dunes 9 Maintaining a Balanced Food Web Sea Turtles and Jellyfish Sea Turtles Provide Food for Fish 11 Nutrient Cycling Loggerheads Benefit Ocean Floor Ecosystems Sea Turtles Improve Nesting Beaches 12 Providing Habitat 14 The Risk of Ecological Extinction 15 Conclusions oceana.org/seaturtles 1 S E L T R U T PHOTO TIM CALVER 2 OCEANA | Protecting the World’s Oceans EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sea turtles have played vital roles in maintaining the health of the world’s oceans for more than 100 million years. These roles range from maintaining productive coral reef ecosystems to transporting essential nutrients from the oceans to beaches and coastal dunes. Major changes have occurred in the oceans because sea turtles have been virtually eliminated from many areas of the globe. Commercial fishing, loss of nesting habitat and climate change are among the human-caused threats pushing sea turtles towards extinction. -

Ecol 483/583 – Herpetology Lab 11: Reptile Diversity 3: Testudines and Crocodylia Spring 2010

Ecol 483/583 – Herpetology Lab 11: Reptile Diversity 3: Testudines and Crocodylia Spring 2010 P.J. Bergmann & S. Foldi Lab objectives The objectives of today’s lab are to: 1. Familiarize yourselves with extant diversity of the Testudines and Crocodylia. 2. Learn to identify species of Testundines that live in Arizona. Today's lab is the final lab on "reptile" diversity, and will introduce you to the Testudines, or turtles and tortoises, Crocodylia. Although there are no crocodylians in Arizona and the Testudine diversity is lower than that of the lizards or snakes, there is still a fair amount of material to learn, so use your time wisely. Tips for learning the material At this point in the course, your skills for learning herp diversity should be well honed, so continue with the strategies you have already learned during the semester. Learn how to differentiate the three major clades of Crocodylians, and the more numerous Testudine clades. There is another keying exercise in this lab, focusing on the Testudines. 1 Ecol 483/583 – Lab 11: Testudines & Crocs 2010 Exercise 1: Testudines (Modified from Bonine & Foldi 2008; Bonine, Dee & Hall 2006; Edwards 2002; Prival 2000) General information Turtles are probably the most instantly recognizable groups of all reptiles because of their shell and the ability to withdraw their heads and limbs into this protective structure. Turtles are a monophyletic group comprising the order Testudines also called Chelonia . Testudines is the term used to denote all members of the order (extant and extinct) whereas Chelonia is often used to denote extant turtles. -

A Field Guide to South Dakota Turtles

A Field Guide to SOUTH DAKOTA TURTLES EC919 South Dakota State University | Cooperative Extension Service | USDA U.S. Geological Survey | South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks This publication may be cited as: Bandas, Sarah J., and Kenneth F. Higgins. 2004. Field Guide to South Dakota Turtles. SDCES EC 919. Brookings: South Dakota State University. Copies may be obtained from: Dept. of Wildlife & Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University Box 2140B, NPBL Brookings SD 57007-1696 South Dakota Dept of Game, Fish & Parks 523 E. Capitol, Foss Bldg Pierre SD 57501 SDSU Bulletin Room ACC Box 2231 Brookings, SD 57007 (605) 688–4187 A Field Guide to SOUTH DAKOTA TURTLES EC919 South Dakota State University | Cooperative Extension Service | USDA U.S. Geological Survey | South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota Department of Game, Fish & Parks Sarah J. Bandas Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University NPB Box 2140B Brookings, SD 57007 Kenneth F. Higgins U.S. Geological Survey South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit South Dakota State University NPB Box 2140B Brookings, SD 57007 Contents 2 Introduction . .3 Status of South Dakota turtles . .3 Fossil record and evolution . .4 General turtle information . .4 Taxonomy of South Dakota turtles . .9 Capturing techniques . .10 Turtle handling . .10 Turtle habitats . .13 Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii) . .15 Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) . .17 Spiny Softshell Turtle (Apalone spinifera) . .19 Smooth Softshell Turtle (Apalone mutica) . .23 False Map Turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) . .25 Western Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata ornata) .