CHAPTER-I! FORMATION of DEVASWOM DEPARTMENT The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8445/the-legend-marthanda-varma-1-c-parthiban-sarathi-1-ii-m-a-history-scott-christian-college-autonomous-nagercoil-488445.webp)

The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 2, Issue 12, December 2017 The legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil. Abstract:-- Marthanda Varma the founder of modern Travancore. He was born in 1705. Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma rule of Travancore in 1929. Marthanda Varma headquarters in Kalkulam. Marthanda Varma very important policy in Blood and Iron policy. Marthanda Varma reorganised the financial department the palace of Padmanabhapuram was improved and several new buildings. There was improvement of communication following the opening of new Roads and canals. Irrigation works like the ponmana and puthen dams. Marthanda Varma rulling period very important war in Battle of Colachel. The As the Dutch military team captain Eustachius De Lannoy and our soldiers surrendered in Travancore king. Marthanda Varma asked Dutch captain Delannoy to work for the Travancore army Delannoy accepted to take service under the maharaja Delannoy trained with European style of military drill and tactics. Commander in chief of the Travancore military, locally called as valia kapitaan. This king period Padmanabhaswamy temple in Ottakkal mandapam built in Marthanda Varma. The king decided to donate his recalm to Sri Padmanabha and thereafter rule as the deity's vice regent the dedication took place on January 3, 1750 and thereafter he was referred to as Padmanabhadasa Thrippadidanam. The legend king Marthanda Varma 7 July 1758 is dead. Keywords:-- Marthanda Varma, Battle of Colachel, Dutch military captain Delannoy INTRODUCTION English and the Dutch and would have completely quelled the rebels but for the timidity and weakness of his uncle the Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma was a ruler of the king who completed him to desist. -

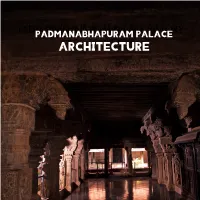

Padmanabhapuram Architecture

PADMANABHAPURAMPADMANABHAPURAM PALACE PALACE HISTORY ARCHITECTURE Padmanabhapuram Palace Architecture 1 Padmanabhapuram Palace Architecture Padmanabhapuram Palace, a veritable architectural marvel, is a harmonious blend of imposing edifices, intricate woodwork and impeccable craftsmanship. Over 400 years old, it spans an area of 6.5 acres and encompasses more than 15 distinctive structures. Hailed as the largest wooden palace in all of Asia, Padmanabhapuram Palace is a testament to the might of the erstwhile Travancore dynasty as well as the unparalleled skill of the artisans of yore. Padmanabhapuram Palace Architecture 2 Contents Mukhya Vathil and Forecourt 01 Poomukhamalika 02 Mani Meda 03 Thai Kottaram 04 Plamuttu Kottaram 05 Valiya Oottupura and Homappura 06 Uppirikka Malika 07 Ayudhappura 08 Ambari Mukhappu 09 Navarathri Mandapam 10 Padmanabhapuram Palace Architecture 3 Mukhya Vathil and Forecourt ukhya Vathil or gateway is the main entrance of the palace, through which Mone can catch a glimpse of the splendours that await inside. Massive doors mounted with metal spikes and the impressively large walls offered protection against enemies. The doorway opens into the forecourt, which used to be the hub of activity in the ancient days, with the king conducting wrestling matches or armed combat for entertainment. An elegant museum block has been seamlessly integrated into the southern part of the forecourt. Padmanabhapuram Palace Architecture 1 Poomukhamalika y crossing the elaborate gateway, flanked on both sides by carved stone pillars, is called the padippura. It has a natamalika or upper storey that connects the various sections of Bthe palace complex. Its crowning glory is an ostentatious overhead bay window through which one gets a panoramic view of the quadrangle, as well as the courtyard ahead of the poomukhamalika (entrance hall). -

Historicity Research Journal

ISSN: 2393-8900 Impact Factor : 1.9152(UIF) VolUme - 4 | ISSUe - 9 | may - 2018 HIStorIcIty reSearcH JoUrNal ________________________________________________________________________________________ HISTORICAL ENQUIRY OF COLACHEL Dr. Praveen O. K. Assistant Professor, Department Of History, Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur, Kerala, India. ABSTRACT Travancore was the princely state existed in South India. It was called by different name in different period, it is popular being Venad, Vanchidesam and Tiruadidesam. Venad is originally known as Vanavanad which Merans the abode of the Dedvas. This was later simplified into Venad. Vanchi Desam means either the land of treasure or the land Baboons. In Malayalam the name of Travancore was interpreted by ‘Thiruvithamkure’ and in Sankrit ‘Srivardhanapuri’. KEY WORDS: Colachel, Battle of Colachel, Marthanda Varma, The Dutch, De Lannoy, Trade relations, The Dutch East India Company. INTRODUCTION Marthanda Varma inherited the throne of Travancore formerly known as Venad,from King Ramavarma, his uncle. During the period of Marthanda Varma the war held in Colachel is significance than the others. This war raises the war power of the king. In 1740, the Dutch Governor says to Marthanda Varma,that he was going to capture Travancore to his control. It internal idea is that Dutch are thinking to make colony in Travancore. In the beginning,and the war came to end of August 7,1741. The war was the important turning point of Marthanda Varma and Travancore State. NEED FOR THE PRESENT STUDY Colachal is sea port town from the ancient past, served as an important commercial centre for the Cheras, Pandyas and even the Dutch. It is surrounded by small villege lioke Kottilpadu, on the south, Puthutheru on the east, Velliyakulam on the North and Kalimar on the West. -

University of Iowa Eco-Sensitive Low-Cost Housing: the Kerala Experience

University of Iowa Eco-sensitive Low-cost Housing: The Kerala experience India Winterim program 2011-12: December 27, 2011-January 15, 2012 Instructor: Jerry Anthony ([email protected]) Winterim India Program Coordinator: R. Rajagopal ([email protected]) Course description Good quality housing is a basic human need. However, it is not always available or if available is not priced at reasonable levels. This forces millions of families all over the world to live in bad quality or unaffordable housing, causing significant socio-economic, physical and financial problems. The scope and scale of the housing shortage is markedly greater in developing countries: one, because of the sheer number of people that need such housing, and two, because of the lack of public and private resources to address this crisis. These constraints have forced governments and non-profits in developing countries such as India to devise innovative lower-cost housing construction technologies that feature a high labor component, use many renewable resources, and have low impacts on the environment. This course will provide an extraordinary opportunity to advanced undergraduate and graduate students and interested persons from Iowa, to travel to India, interact with highly acclaimed housing professionals, learn about many innovative eco-sensitive housing techniques, and conduct independent research on a housing topic of one’s choice. All course participants will develop a clearer understanding of the conflicting challenges of economic development and environmental protection, and of culture, politics and the uneven geography of opportunity in a developing country. The course will be located in the city of Trivandrum (also called Thiruvananthapuram), the capital city of the state of Kerala. -

Kodaiyar River Basin

Kodaiyar River Basin Introduction One of the oldest systems in Tamil Nadu is the “Kodaiyar system” providing irrigation facilities for two paddy crop seasons in Kanyakumari district. The Kodaiyar system comprises the integrated operation of commands of two major rivers namely Pazhayar and Paralayar along with Tambaraparani or Kuzhithuraiyur in which Kodaiyar is a major tributary. The whole system is called as Kodaiyar system. Planning, development and management of natural resources in this basin require time-effective and authentic data.The water demand for domestic, irrigation, industries, livestock, power generation and public purpose is governed by socio – economic and cultural factors such as present and future population size, income level, urbanization, markets, prices, cropping patterns etc. Water Resources Planning is people oriented and resources based. Data relating to geology, geomorphology, hydrogeology, hydrology, climatology, water quality, environment, socio – economic, agricultural, population, livestock, industries, etc. are collected for analysis. For the sake of consistency, other types of data should be treated in the same way. Socio – economic, agricultural and livestock statistics are collected and presented on the basis of administrative units located within this basin area. Location and extent of Kodaiyar Basin The Kodaiyar river basin forms the southernmost end of Indian peninsula. The basin covers an area of 1646.964 sq km. The flanks of the entire basin falls within the TamilnaduState boundary. Tamiraparani basin lies on the north and Kodaiyar basin on the east and Neyyar basin of Kerala State lies on the west. This is the only river basin which has its coastal border adjoining the Arabian sea, the Indian Ocean in the south and the Gulf of Mannar in the east. -

Early Irrigation Systems in Kanyakumari District

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 January 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 EARLY IRRIGATION SYSTEMS IN KANYAKUMARI DISTRICT Dr.H.Santhosha kumarai Assistant professor Department of History and Research Centre Scott Christian college (Autonomous), Nagercoil ABSTRACT: The study has been under taken to analyse the early irrigation systems in kanyakumari district. Ay kings who ruled between 4th century BC and 9th century A.D showed interests in developing the irrigation systems. The ancient Tamils found a good system of distribution management of Water.The Rivers are the back bones of irrigation in kanyakumari district. During early period tanks were created with a clear idea to meet the needs of the people The earlier irrigation systems were well planned aiming at the welfare and benefit of the people . The irrigation system that was developed during the early period in kanyakumari district is still continuing and helping the people. Key words - irrigation system, rivers, tanks, welfare and benefit. 1. INTRODUCTION Kanyakumari district differs from the rest of Tamil Nadu with regard to its physical features and all other aspects, such as people and culture. The normal rainfall is more than forty inches a year. Kanyakuamri District presents a striking contrast to the neighbouring Tirunelveli and Kerala state in point of physical features and agricultural conditions. The North eastern part of the district is filled with hills and mountains. The Aralvaimozhi hills and the Aralvaimozhi pass are historically important( Gopalakrishnan, 1995,).The fort at the top of the hill was built by the ancient kings to defend the Ay kingdom. Marunthuvalmalai or the medicinal hill is referred in the epic of Ramayana. -

Kanyakumari District, Tamil Nadu

For official use Technical Report Series DISTRICT GROUNDWATER BROCHURE KANYAKUMARI DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU A. Balachandran Scientist - D Government of India Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board South Eastern Coastal Region Chennai September 2008 0 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE (KANYAKUMARI) S. No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical area (Sq. km) 1671.84 ii. Administrative Divisions (As on 31-3-2007) Number of Taluks 4 Number of Blocks 9 Number of Villages 81 iii. Population (As on 2001 Censes) Total Population 1676034 Male 832269 Female 843765 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1448.6 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY i. Major physiographic Units (i). Western Ghats (ii). Coastal Plain. ii. Major Drainages Pazhayar, Valliyar & Tamirabarani. 3. LAND USE (Sq. km) (2005-06) i. Forest area 541.55 ii. Net area sown 793.23 iii. Barren & Uncultivable waste 31.49 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES 1. Red soil 2. Lateritic soil 3. Clayey soil, 4. River Alluvium & 5. Coastal Alluvium. 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (Ha.) 1. Paddy -21709 (56%) (2005-2006) 1. Coconut – 9388 (24%) 2. Banana – 5509 (14.2%) 4. Pulses – 166 (< 1 %) 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (2005-06) Number Area irrigated (Ha.) i. Dug wells 3349 1535 ii. Tube wells 1303 913 iii. Tanks 2623 13657 iv. Canals 53 22542 vi. Net irrigated area 27694 Ha. vii. Gross irrigated area 38885 Ha. 1 7. NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (As on 31.03.2007) i. Dug wells 14 ii. Piezometers 8 8. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Recent Alluvium, & Warkalai FORMATIONS Sandstones, Peninsular Gneisses Charnockites, Khondalites, Granites and Pegmatites 9. -

Padmanabhapuram Palace 1 Padmanabhapuram | India Several Architects

Padmanabhapuram Palace 1 Padmanabhapuram | India several architects 1 2 3 4 5 7 6 7 8 9 11 10 2 13 12 14 15 Aspects geography | Topography | Vegetation The city of Padmanabhapuram has warm climate with temperatures around 30°C all year and a high amount of humidity. There is a rainy season from april to december. The temple is located at 15 meters above sea level and surrounded by forest, fields and the town of Padmanbhapuram. Building volume | Zoning The palace complex is composed of many buildings from different periods that are connected by covered corridors and overhead walkways. The mother’s palace or the ‘Thai Kottaram’ is the oldest building and core of complex. Other buildings like the „Mantrashala“ (used for the kings meetings) or the „Veppinmuttu Kot- taram“ (used as residence) were added later and shape the complex structure. Usually the upper floors were used as the main living area. There are many external and internal courtyards on the complex that improve the lighting and ventilation in the interiors as well as two ponds. Material | Construction The Palace is constructed of wood, limeplaster and different bricks and stones. Timber was used for the construction of the walls, the roof frame, beams and pillars. Some building‘s walls are made of laterite, granite or bricks or a combination of them and the main walls are coated with lime plaster and sea-shell lime. The Palace is secured by a stone fortification and the floor of some buildings consists of lime mixed with herbs that was polished. Building shell | Shadow | Ventilation The upper areas of some buildings are ventilated at the roof ridge by wooden screens called „jaalis“, that filter the light inside and allow air to flow through. -

Lions Clubs International

Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 324B4 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 26466 ARUPPUKOTTAI President 26466 ARUPPUKOTTAI Secretary 26466 ARUPPUKOTTAI Treasurer 26487 KULASEKHARAM President 26487 KULASEKHARAM Secretary 26487 KULASEKHARAM Treasurer 26492 NAGERCOIL President 26492 NAGERCOIL Secretary 26492 NAGERCOIL Treasurer 26507 TIRUNELVELI President 26507 TIRUNELVELI Secretary 26507 TIRUNELVELI Treasurer 30844 SRIVILLIPUTHUR President 30844 SRIVILLIPUTHUR Secretary 30844 SRIVILLIPUTHUR Treasurer 40829 WATRAP President 40829 WATRAP Secretary 40829 WATRAP Treasurer 43432 SATHUR President 43432 SATHUR Secretary 43432 SATHUR Treasurer 43948 ALANGULAM President 43948 ALANGULAM Secretary 43948 ALANGULAM Treasurer 49095 TUTICORIN CHIDAMBARANAR President 49095 TUTICORIN CHIDAMBARANAR Secretary 49095 TUTICORIN CHIDAMBARANAR Treasurer 49425 NEYYOOR MONDAY MARKET President 49425 NEYYOOR MONDAY MARKET Secretary 49425 NEYYOOR MONDAY MARKET Treasurer 49550 RAMANATHAPURAM SETHUPATHY President 49550 RAMANATHAPURAM SETHUPATHY Secretary 49550 RAMANATHAPURAM SETHUPATHY Treasurer OFF0021 Run Date: 7/8/2010 11:44:30AM Page 1 of 5 Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 324B4 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 50048 KARINGAL President 50048 KARINGAL Secretary 50048 KARINGAL Treasurer 50051 TUTICORIN BHARATHY President 50051 TUTICORIN BHARATHY Secretary 50051 TUTICORIN -

District AC No. Name of the Assembly Constituency Male Female Third

AC wise Electorate as on 20/01/2016 (Final publication of Electoral Rolls) Name of the Assembly Third District AC No. Male Female Total Constituency Gender 1 Gummidipoondi 1,27,756 1,31,407 31 2,59,194 2 Ponneri 1,22,602 1,24,768 60 2,47,430 3 Tiruttani 1,35,217 1,38,638 32 2,73,887 4 Thiruvallur 1,25,393 1,28,944 22 2,54,359 5 Poonamallee 1,54,104 1,54,937 42 3,09,083 1. Thiruvallur 6 Avadi 1,95,387 1,91,799 75 3,87,261 7 Maduravoyal 1,99,463 1,92,121 109 3,91,693 8 Ambattur 1,79,372 1,74,045 101 3,53,518 9 Madavaram 1,99,588 1,97,596 81 3,97,265 10 Thiruvottiyur 1,43,737 1,43,069 66 2,86,872 Total 15,82,619 15,77,324 619 31,60,562 11 Dr.Radhakrishnan Nagar 1,25,881 1,29,229 88 2,55,198 12 Perambur 1,43,844 1,45,019 38 2,88,901 13 Kolathur 1,29,587 1,32,273 53 2,61,913 14 Villivakkam 1,24,897 1,27,337 58 2,52,292 15 Thiru-Vi-Ka-Nagar 1,05,514 1,09,575 31 2,15,120 16 Egmore 94,933 95,983 33 1,90,949 17 Royapuram 91,952 94,394 40 1,86,386 18 Harbour 96,017 86,751 52 1,82,820 2. Chennai 19 Chepauk-Thiruvallikeni 1,11,748 1,14,152 20 2,25,920 20 Thousand Lights 1,19,944 1,23,364 78 2,43,386 21 Anna Nagar 1,41,481 1,43,634 50 2,85,165 22 Virugampakkam 1,44,327 1,41,652 67 2,86,046 23 Saidapet 1,38,982 1,40,160 65 2,79,207 24 Thiyagarayanagar 1,19,860 1,20,447 45 2,40,352 25 Mylapore 1,25,305 1,31,697 30 2,57,032 26 Velachery 1,48,142 1,48,099 88 2,96,329 Total 19,62,414 19,83,766 836 39,47,016 Name of the Assembly Third District AC No. -

To Whom Does Temple Wealth Belong? a Historical Essay on Landed Property in Travancore K

RESEARCH ARTICLE To Whom Does Temple Wealth Belong? A Historical Essay on Landed Property in Travancore K. N. Ganesh* Abstract: The enormous wealth stored in the Sree Padmanabha Swamy temple of Thiruvananthapuram, the component items of which were classified and enumerated under the direction of the Supreme Court of India in June 2011, sparked off a major debate on the nature of temple wealth, and on the rights of the temple, the royal family that controlled the temple, and the people as a whole. The issues that have figured in the current controversy can be addressed only by means of study of the history of the growth of temples and their wealth. The Padmanabha temple, where the present hoard has been discovered, is a case in point. In the medieval context, the transformation of landed social wealth into temple wealth impelled the emergence of the temple as a source of social power, one that even kings were forced to recognise. Ultimately, whether described as divine wealth or social wealth, this wealth belongs to the people as the proceeds of their labour. The millions hoarded in the Padmanabha temple are the historical legacy of the millions who have tilled the soil and laboured on the earth for at least a millennium, and shall go back to them and their inheritors. Keywords: Sree Padmanabha Swamy temple, history of Travancore, agrarian history of Kerala, Venad kingdom, temple hoard. The enormous wealth stored in the Sree Padmanabha Swamy temple of Thiruvananthapuram,1 the component items of which were classified and enumerated under the direction of the Supreme Court of India in June 2011, sparked off a major debate on the nature of temple wealth and on the rights of the temple, the royal family that controls the temple, and the people as a whole. -

Kanyakumari District

KANYAKUMARI DISTRICT 1 KANYAKUMARI DISTRICT 1. Introduction i) Geographical location of the district Kanyakumari is the Southern most West it is bound by Kerala. With an area of district of Tamil Nadu. The district lies 1672 sq.km it occupies 1.29% of the total between 77 o 15 ' and 77 o 36 ' of the Eastern area of Tamil Nadu. It ranks first in literacy Longitudes and 8 o 03 ' and 8 o 35 ' of the among the districts in Tamil Nadu. Northern Latitudes. The district is bound by Tirunelveli district on the North and the East. ii) Administrative profile The South eastern boundary is the Gulf of The administrative profile of Mannar. On the South and the South West, Kanyakumari district is given in the table the boundaries are the Indian Ocean and the below Arabian sea. On the west and North Name of the No. of revenue Sl. No. Name of taluk No. of firka division villages 1 Agastheeswaram 4 43 1 Nagercoil 2 Thovalai 3 24 3 Kalkulam 6 66 2 Padmanabhapuram 4 Vilavancode 5 55 Total 18 188 ii) 2 Meteorological information and alluvial soils are found at Based on the agro-climatic and Agastheeswaram and Thovalai blocks. topographic conditions, the district can be divided into three regions, namely: the ii) Agriculture and horticulture uplands, the middle and the low lands, which are suitable for growing a number of crops. Based on the agro-climatic and The proximity of equator, its topography and topographic conditions, the district can be other climate factors favour the growth of divided into three regions, namely:- various crops.