WHOI-98-16.Pdf (9.941Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Woonsocket, Ri

2018 HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN UPDATE – WOONSOCKET, RI 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update City of Woonsocket, Rhode Island PREPARED FOR City of Woonsocket, RI City Hall 169 Main Street Woonsocket, RI 02895 401-762-6400 PREPARED BY 1 Cedar Street Suite 400 Providence, RI 02908 401.272.8100 JUNE/JULY 2018 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Woonsocket, RI This Page Intentionally Left Blank. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Plan Purpose .................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Hazard Mitigation and Benefits .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Goals.................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Background .................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 History ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Game Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 GAME CHANGER HOW COACH BUDDY TEEVENS ’79 TURNED LOSERS INTO CHAMPIONS—AND TRANSFORMED THE GAME OF FOOTBALL FOREVER FIVE DOLLARS H W’ P B B FINE HANDCRAFTED VERMONT FURNITURE CELEBRATING 4 5 YEARS OF CRAFTSMANSHIP E E L L C C 5 T G, W, VT 802.457.2600 23 S M S, H, NH 603.643.0599 NH @ . . E THETFORD, VT FLAGSHIP SHOWROOM + WORKSHOP • S BURLINGTON, VT • HANOVER, NH • CONCORD, NH NASHUA, NH • BOSTON, MA • NATICK, MA • W HARTFORD, CT • PHILADELPHIA, PA POMPY.COM • 800.841.6671 • We Offer National Delivery S . P . dartmouth_alum_Aug 2018-5.indd 1 7/22/18 10:23 PM Africa’s Wildlife Inland Sea of Japan Imperial Splendors of Russia Journey to Southern Africa Trek to the Summit with Dirk Vandewalle with Steve Ericson with John Kopper with DG Webster of Mt. Kilimanjaro March 17–30, 2019 May 22–June 1, 2019 September 11–20, 2019 October 27–November 11, 2019 with Doug Bolger and Celia Chen ’78 A&S’94 Zimbabwe Family Safari Apulia Ancient Civilizations: Vietnam and Angkor Wat December 7–16, 2019 and Victoria Falls with Ada Cohen Adriatic and Aegean Seas with Mike Mastanduno Faculty TBD June 5–13, 2019 with Ron Lasky November 5–19, 2019 Discover Tasmania March 18–29, 2019 September 15–23, 2019 with John Stomberg Great Journey Tanzania Migration Safari January 8–22, 2020 Caribbean Windward Through Europe Tour du Montblanc with Lisa Adams MED’90 Islands—Le Ponant with John Stomberg with Nancy Marion November 6–17, 2019 Mauritius, Madagascar, with Coach Buddy Teevens ’79 June 7–17, 2019 September 15–26, 2019 -

2.4 Winter Storm

State of Ohio Enhanced Hazard Mitigation Plan Rev. May 2014 2.4 WINTER STORM Canadian and Arctic cold fronts that push cold temperatures, ice, and snow into the State generally cause winter storms, blizzards, and ice storms in Ohio. Severe winter weather in Ohio consists of freezing temperatures and heavy precipitation, usually in the form of snow, freezing rain, or sleet. Severe winter weather affects all parts of the State. Blizzard conditions occur when the following conditions last three hours or longer: · 35 mph or greater wind speeds, · considerable snowfall and blowing snow bringing visibility below ¼ mile, and, · temperatures of 20º F or lower. Severe blizzards have wind speeds exceeding 45 mph, visibility near zero, and temperatures of 10º F or lower. While Ohio residents and governments are accustomed to handling winter storm events, occasional extreme events can make conditions dangerous and disruptive. Heavy snow volume makes snow removal difficult. Trees, cars, roads, and other surfaces develop a coating of ice, making even small accumulations of ice extremely hazardous to motorists and pedestrians. The most prevalent impacts of heavy accumulations of ice are slippery roads and walkways that lead to vehicle and pedestrian accidents; collapsed roofs from fallen trees and limbs from heavy ice and snow loads; and felled trees, telephone poles and lines, electrical wires, and communication towers. As a result of severe ice storms, telecommunications and power can be disrupted for days. The northeastern portion of Ohio near the Great Lakes experiences what is known as “lake-effect snow” (see Figure 2.4.a). As cold air passes over the relatively warm waters of the large lakes, the weather system absorbs moisture and heat, and releases this in the form of snow. -

2017 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Coventry, Ri

2017 HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN UPDATE – COVENTRY, RI 2017 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update Town of Coventry, Rhode Island PREPARED FOR Town of Coventry, RI Town Hall 1670 Flat River Road Coventry, RI 02816 401-821-6400 PREPARED BY 101 Walnut Street PO Box 9151 Watertown, MA 02471 617.924.1770 MAY 2017 2017 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Coventry, RI This Page Intentionally Left Blank. 2017 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Coventry, RI Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Plan Purpose .................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Hazard Mitigation and Benefits .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Goals.................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Background .................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 History ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

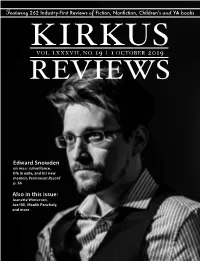

Edward Snowden Also in This Issue

Featuring 262 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVII, NO. 19 | 1 OCTOBER 2019 REVIEWS Edward Snowden on mass surveillance, life in exile, and his new memoir, Permanent Record p. 56 Also in this issue: Jeanette Winterson, Joe Hill, Maulik Pancholy, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Stories for Days HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, recently Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER told her Twitter followers that she has been reading a short story a day and [email protected] Vice President of Marketing that “it has been a deeply satisfying little project.” Lisa’s tweet reminded SARAH KALINA me of a truth I often lose sight of: You’re not required to read a story col- [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor lection cover to cover, all at once, as if it were a novel. As a result, I’ve ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] started hopscotching among stories by old favorites such as Lorrie Moore, Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Deborah Eisenberg, and Alice Munro. I’ve also turned my attention to [email protected] Children’s Editor some collections that are new this fall. Here are three: VICKY SMITH Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale edited by Lauren [email protected] Young Adult Editor Tom Beer Groff (Library of America, Oct. 1). Like so many neglected women writers of LAURA SIMEON [email protected] short fiction from the middle of the 20th century—Maeve Brennan, Edith Templeton, Mary Ladd Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE Gavell—Hale isn’t widely read today and is ripe for rediscovery. -

October 16, 2016 -- 61 Years

Sixty-One YEARS OF COMMUNITY NEWS Sunday, October 16, 2016 • Featured Section 1955 - 2016 2 Sunday, October 16, 2016 SIXTY-ONE YEARS www.tctimes.com Publisher Rick Rockman, Sr. promised January 1997, we left our offices at the that the new paper would provide Fenton Mini-Mall on North Leroy Street, complete, in-depth coverage of all area and moved into a new state-of-the-art news and activities. We believe he had facility on Fenway Drive in Fenton’s not only lived up to that promise, but industrial park and added a print shop exceeded the community’s expectations and mailing house called Allied Media by the many additions and improvements (formerly Allied Mailing & Printing) not only to the Sunday newspaper, but along with Rockman & Sons Publishing. with the addition of TCTimes online In November 2003, we added the (tctimes.com) in 1997, and the addition final phase of our communications of the Wednesday Midweek edition in network by creating a full service ISP, September 1999. Tri-County Wireless. The rapid growth of “This area desperately needs a your hometown newspaper then made it TRI-COUNTY TIMES | FILE PHOTO newspaper with local news,” said necessary for us to build yet another new Due to the success of the Tri-County Times, a second state-of-the-art facility was Rockman in April 1994. “We feel that building, directly next door to our facility opened in 2005. the hometown paper concept has all but on Fenway Drive in 2005. disappeared over the last few years. We’ll Serving you, our valuable readers, and focus on local news and events that are advertisers always has and always will of interest and concern to the citizens of be our top priority, and we thank you for The Tri-County Times this area.” your continued support. -

2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Coventry, Ri

2018 HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN UPDATE – COVENTRY, RI 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update Town of Coventry, Rhode Island PREPARED FOR Town of Coventry, RI Town Hall 1670 Flat River Road Coventry, RI 02816 401-821-6400 PREPARED BY 101 Walnut Street PO Box 9151 Watertown, MA 02471 617.924.1770 ADOPTED FEBRUARY 2018 2018 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – Coventry, RI This Page Intentionally Left Blank. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Plan Purpose .................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Hazard Mitigation and Benefits .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Goals.................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Background .................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 History ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Article a Meteorological and Social Comparison of the New England

Call, D. A., K. E. Grove, and P. J. Kocin, 2015: A meteorological and social comparison of the New England blizzards of 1978 and 2013. J. Operational Meteor., 3 (1), 110, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15191/nwajom.2015.0301. Journal of Operational Meteorology Article A Meteorological and Social Comparison of the New England Blizzards of 1978 and 2013 DAVID A. CALL and KATELYN E. GROVE Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana PAUL J. KOCIN NOAA/NWS/NCEP Weather Prediction Center, Riverdale, Maryland (Manuscript received 7 July 2014; review completed 25 November 2014) ABSTRACT The Northeast United States Blizzard of February 1978 was an intense snowstorm that deposited >30 cm of snow on much of the northeastern United States and disrupted life for millions of residents. The disruption was perhaps greatest in and around Boston, where >60 cm of snow fell on a busy Monday, stranding thousands of commuters. Severe coastal flooding also caused major damage. For many area residents, life did not return to normal until the following week. In 2013, a meteorologically similar blizzard once again affected the northeastern United States. Like before Boston received >60 cm of snow—disrupting business and routine. However, the disruption was much shorter in duration. Few people were stranded on roadways, children only missed a few days of school, and the airport closed for less than one day. The authors of this paper examined meteorological data, newspapers, and other accounts and information about the two storms to determine why the societal impacts were so different. Weather forecasting has improved significantly in the 35 yr separating the storms, and this is one very important factor. -

The Great Blizzards of 1978

The Great Blizzards of 1978 1978-02-04 to 1978-02-08 This blizzard was a Cat 4 for the Northeast Region that packed hurricane force winds, record breaking snowfall and white out conditions. Heavy snow fell from northeastern Maryland into Maine. Record snowfall smothered Long Island, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. A small portion of Rhode Island reported over 50 inches of snow and many schools and businesses across the area were closed for over a week. (Kocin and Uccellini) The Great Blizzard of 1978 (The Cleveland Superbomb) 1978-01-23 to 1978-01-28 This blizzard produced the second lowest atmospheric pressure ever recorded over the contiguous U.S from a non-tropical system. The Upper Midwest Region felt the full extent of the storm as a Cat 5 and the Ohio Valley Region experienced a Cat 3 storm. Indiana, Ohio and Michigan all declared states of emergency and had widespread travel cessation. South Bend, IN picked up 3 feet with many parts of southern Michigan buried in 2 feet. Heavy snow accompanied by 55 mph winds produced 10 to 20 foot drifts across the area causing many cities to completely shut down. January 19-20, 1978 A strong Nor'easter developed off the Southeast Coast. It was the third snow in a week for Virginia. Charlottesville got a foot of snow, with up to 30 inches in the west central mountains of Virginia. East of the mountains saw 4 to 8 inches until you reached Richmond. Richmond received a devastating ice storm causing major power disruptions and tree damage. -

2019 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update – South Kingstown, Ri

2019 HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN UPDATE – SOUTH KINGSTOWN, RI 2019 Hazard Mitigation Plan Update Town of South Kingstown, Rhode Island PREPARED FOR Town of South Kingstown Town Hall 180 High Street Wakefield, RI 02879 401-789-9331 PREPARED BY 1 Cedar Street Suite 400 Providence, RI 02903 401-272-8100 January 2, 2019 This page intentionally left blank. RESOLUTION NO. XXXX-XX A RESOLUTION OF THE TOWN COUNCIL OF THE TOWN OF SOUTH KINGSTOWN AUTHORIZING THE ADOPTION OF THE 2019 SOUTH KINGSTOWN HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN UPDATE WHEREAS, the Town of South Kingstown recognizes exposure to natural hazards that increase the risk to life, property, environment, within our community; and WHEREAS; pro-active mitigation of known hazards before a disaster event can reduce or eliminate long-term risk to life and property; and WHEREAS, The Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (Public Law 106-390) established new requirements for pre and post disaster hazard mitigation programs; and WHEREAS; the 2019 Plan identifies mitigation goals and actions to reduce or eliminate long-term risk to people and property in South Kingstown from impacts of future hazards and disasters; and WHEREAS, adoption by the Town Council demonstrates their commitment to hazard mitigation and achieving goals outlined in the 2018 South Kingstown Hazard Mitigation Plan Update. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED that the Town of South Kingstown 1) Adopts in its entirety, the 2019 South Kingstown Hazard Mitigation Plan Update (the “Plan”) as the jurisdiction’s Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan and resolves to execute the actions identified in the Plan that pertain to this jurisdiction. 2) Will use the adopted and approved portions of the Plan to guide pre- and post-disaster mitigation of the hazards identified. -

Medway in 1713 Included the Land We Presently Know As Millis and Medway

COMMUNITY CHURCH HISTORY The incorporation of Medway in 1713 included the land we presently know as Millis and Medway. The two sections are often re- ferred to as the East Precinct (Millis), and the West Precinct (Medway). The Black Swamp, a massive area of dense forests and swamps, was the geographical center between both precincts. The First Church of Christ in Medway was established in the more populous area east of the Black Swamp. In colonial days, attendance at church services was an obligation. Services were lengthy, involving both morning and afternoon sessions, with a short intermission to eat, warm up if it was cold, and socialize in the adja- cent “noon houses.” Weather was always an issue, but winter was especially difficult due to the cold and lack of heat in the meet- ing house. As the population of Medway grew, settlers began building in the West Precinct. Increasingly, as early as 1731, they began to ex- plore alternatives to attending church services and town meetings at such a distance. The Black Swamp was a major obstacle to these settlers and their families, who travelled by foot, wagon, or horseback to attend services in the east. It was difficult, inconve- nient, and nearly impossible to travel several miles from home, over rutted pathways, across the often flooded swampy area, to -ar rive at the meeting house in time to hear the bell ringing, calling all to worship. Several proposals were made to make it easier for the West Precinct settlers to attend worship services. After failing to find a work- able solution, the settlers petitioned the General Court in 1748 for permission to separate from the East Precinct and to build their own meeting house. -

Weather-Adjusting Economic Data

MICHAEL BOLDIN Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia JONATHAN H. WRIGHT Johns Hopkins University Weather-Adjusting Economic Data ABSTRACT This paper proposes and implements a statistical methodol ogy for adjusting employment data for the effects of deviations in weather from seasonal norms. This is distinct from seasonal adjustment, which controls only for the normal variation in weather across the year. We simultaneously control for both of these effects by integrating a weather adjustment step in the seasonal adjustment process. We use several indicators of weather, includ ing temperature and snowfall. We find that weather effects can be important, shifting the monthly payroll change number by more than 100,000 in either direction. The effects are largest in the winter and early spring months and in the construction sector. A similar methodology is constructed and applied to data in the national income and product accounts (NIPA), although the manner in which NIPA data are reported makes it impossible to integrate weather and seasonal adjustments fully. acroeconomic time series are affected by the weather. In the first Mquarter of 2014, real GDP contracted by 0.9 percent at an annual ized rate. Commentators and Federal Reserve officials attributed part of the decline to an unusually cold winter and large snowstorms that hit the East Coast and the South during the quarter (Macroeconomic Advisers 2014; Yellen 2014).1 Similarly, the slowdown in growth in the first quarter of 2015 was widely ascribed to another exceptionally harsh winter and other transitory factors (Yellen 2015). While the effects of regular variation in 1. In November 2013, the Survey of Professional Forecasters expected a seasonally adjusted increase of 2.5 percent in 2014Ql.