Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Career of Fernand Faniard

Carrière artistique du Ténor FERNAND FANIARD (9.12.1894 Saint-Josse-ten-Noode - 3.08.1955 Paris) ********** 1. THÉÂTRE BELGIQUE & GRAND DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG BRUXELLES : OPÉRA ROYAL DE LA MONNAIE [1921-1925 : Baryton, sous son nom véritable : SMEETS] Manon [première apparition affichée dans un rôle] 1er & 5 août 1920 Louise (Le Peintre) 2 août 1920 Faust (Valentin) 7 août 1920 Carmen (Morales) 7 août 1920. La fille de Madame Angot (Buteux) 13 avril 1921, avec Mmes. Emma Luart (Clairette), Terka-Lyon (Melle. Lange), Daryse (Amarante), Mercky (Javotte, Hersille), Prick (Thérèse, Mme. Herbelin), Deschesne (Babet), Maréchal (Cydalèse), Blondeau. MM. Razavet (Ange Pitou), Arnaud (Pomponnet), Boyer (Larivaudière), Raidich (Louchard), Dognies (Trénitz), Dalman (Cadet, un officier), Coutelier (Guillaume), Deckers (un cabaretier), Prevers (un incroyable). La fille de Roland (Hardré) 7 octobre 1921 Boris Godounov (création) (Tcherniakovsky), 12 décembre 1921 Antar (création) (un berger) 10 novembre 1922 La victoire (création) (L'envoi) 28 mars 1923 Les contes d'Hoffmann (Andreas & Cochenille) La vida breve (création) (un chanteur) 12 avril 1923 Francesca da Rimini (création) (un archer) 9 novembre 1923 Thomas d'Agnelet (création) (Red Beard, le Lieutenant du Roy) 14 février 1924 Il barbiere di Siviglia (Fiorillo) Der Freischütz (Kilian) La Habanera (Le troisième ami) Les huguenots (Retz) Le joli Gilles (Gilles) La Juive (Ruggiero) Les maîtres chanteurs (Vogelsang) Pénélope (Ctessipe) Cendrillon (Le superintendant) [1925-1926 : Ténor] Gianni Schicchi (Simone) Monna Vanna (Torello) Le roi d'Ys (Jahel) [20.04.1940] GRANDE MATINÉE DE GALA (au profit de la Caisse de secours et d'entr'aide du personnel du Théâtre Royal). Samson et Dalila (2ème acte) (Samson) avec : Mina BOLOTINE (Dalila), Mr. -

Bizet Carmen Mp3, Flac, Wma Related Music Albums To

Bizet Carmen mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Carmen Country: UK Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1148 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1903 mb WMA version RAR size: 1773 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 451 Other Formats: WAV TTA AHX MMF MP3 VOX ADX Label: Decca – LXT 2615 Type: 3 x Vinyl, LP, Mono Country: UK Date of released: Category: Classical Style: Opera Related Music albums to Carmen by Bizet Bizet | Janine Micheau, Nicolai Gedda, Ernest Blanc, Jacques Mars | Chorus And Orchestra Of The Théâtre National De L'Opéra-Comique Conducted By Pierre Dervaux - The Pearl Fishers The Orchestra Of The Paris Opera - Carmen (Highlights) The Rome Symphony Orchestra Under The Direction Of Domenico Savino, Bizet - Carmen Charles Gounod, Georges Bizet, Orchestra Of The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Alexander Gibson - Faust Ballet Music / Carmen Suite Albert Wolff / The Paris Conservatoire Orchestra - Berlioz Overtures Glazunov : L'Orchestre De La Société Des Concerts Du Conservatoire De Paris Conducted By Albert Wolff - The Seasons, Op.67 - Ballet Georges Bizet / Marilyn Horne / James McCracken / Leonard Bernstein / The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra And Chorus - Carmen Bizet | Soloists, Chorus & Orchestra Of The Opéra-Comique, Paris | Albert Wolff - "Carmen" - Highlights Georges Bizet, Maria Callas, Nicolai Gedda, Robert Massard, Andréa Guiot - CARMEN Bizet, Chorus & Orch. Of The Metropolitan Opera Association - Carmen - Excerpts Georges Bizet, Rafael Frühbeck De Burgos, Grace Bumbry, Mirella Freni, Jon Vickers, Kostas Paskalis - Carmen (Highlights) Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Leopold Stokowski, Bizet - Carmen Suite. -

The Contest Works for Trumpet and Cornet of the Paris Conservatoire, 1835-2000

The Contest Works for Trumpet and Cornet of the Paris Conservatoire, 1835-2000: A Performative and Analytical Study, with a Catalogue Raisonné of the Extant Works Analytical Study: The Contest Works for Trumpet and Cornet of the Paris Conservatoire, 1835-2000: A Study of Instrumental Techniques, Forms and Genres, with a Catalogue Raisonné of the Extant Corpus By Brandon Philip Jones ORCHID ID# 0000-0001-9083-9907 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2018 Faculty of Fine Arts and Music The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT The Conservatoire de Paris concours were a consistent source of new literature for the trumpet and cornet from 1835 to 2000. Over this time, professors and composers added over 172 works to the repertoire. Students and professionals have performed many of these pieces, granting long-term popularity to a select group. However, the majority of these works are not well-known. The aim of this study is to provide students, teachers, and performers with a greater ability to access these works. This aim is supported in three ways: performances of under-recorded literature; an analysis of the instrumental techniques, forms and genres used in the corpus; and a catalogue raisonné of all extant contest works. The performative aspect of this project is contained in two compact discs of recordings, as well as a digital video of a live recital. Twenty-six works were recorded; seven are popular works in the genre, and the other nineteen are works that are previously unrecorded. The analytical aspect is in the written thesis; it uses the information obtained in the creation of the catalogue raisonné to provide an overview of the corpus in two vectors. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering By Anya B. Holland-Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 08/24/2012 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan C. Cook, Professor, Music Charles Dill, Professor, Music Lawrence Earp, Professor, Music Nan Enstad, Professor, History Pamela Potter, Professor, Music i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my best creations—my son, Owen Frederick and my unborn daughter, Clara Grace. I hope this dissertation and my musicological career inspires them to always pursue their education and maintain a love for music. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation grew out of a seminar I took with Susan C. Cook during my first semester at the University of Wisconsin. Her enthusiasm for music written during the First World War and her passion for research on gender and music were contagious and inspired me to continue in a similar direction. I thank my dissertation advisor, Susan C. Cook, for her endless inspiration, encouragement, editing, patience, and humor throughout my graduate career and the dissertation process. In addition, I thank my dissertation committee—Charles Dill, Lawrence Earp, Nan Enstad, and Pamela Potter—for their guidance, editing, and conversations that also helped produce this dissertation over the years. My undergraduate advisor, Susan Pickett, originally inspired me to pursue research on women composers and if it were not for her, I would not have continued on to my PhD in musicology. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Sccopland on The

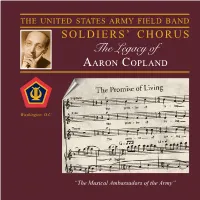

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND SOLDIERS’ CHORUS The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Soldiers’ Chorus, founded in 1957, is the vocal complement of the T United States Army Field Band of Washington, DC. The 29-member mixed choral ensemble travels throughout the nation and abroad, performing as a separate component and in joint concerts with the Concert Band of the “Musical Ambassadors of the Army.” The chorus has performed in all fifty states, Canada, Mexico, India, the Far East, and throughout Europe, entertaining audiences of all ages. The musical backgrounds of Soldiers’ Chorus personnel range from opera and musical theatre to music education and vocal coaching; this diversity provides unique programming flexibility. In addition to pre- senting selections from the vast choral repertoire, Soldiers’ Chorus performances often include the music of Broadway, opera, barbershop quartet, and Americana. This versatility has earned the Soldiers’ Chorus an international reputation for presenting musical excellence and inspiring patriotism. Critics have acclaimed recent appearances with the Boston Pops, the Cincinnati Pops, and the Detroit, Dallas, and National symphony orchestras. Other no- table performances include four world fairs, American Choral Directors Association confer- ences, music educator conven- tions, Kennedy Center Honors Programs, the 750th anniversary of Berlin, and the rededication of the Statue of Liberty. The Legacy of AARON COPLAND About this Recording The Soldiers’ Chorus of the United States Army Field Band proudly presents the second in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contributions to the choral reper- toire and to music education. -

Music of New Orleans a Concert in Honor of Vivian Perlis

Music of New Orleans A Concert in Honor of Vivian Perlis Society for American Music 45th Annual Conference New Orleans, Louisiana 22 March 2019 George and Joyce Wein Jazz & Heritage Center 7:00 p.m. Sarah Jane McMahon, soprano Peter Collins, piano The Society for American Music is delighted to welcome you to the fourth Vivian Perlis Concert, a series of performances of music by contemporary American composers at the society’s annual conferences. We are grateful to the Virgil Thomson Foundation, the Aaron Copland Fund, and to members of the Society for their generous support. This concert series honors Vivian Perlis, whose publications, scholarly activities, and direction of the Oral History of American Music (OHAM) project at Yale University have made immeasurable contributions to our understanding of American composers and music cultures. In 2007 the Society for American Music awarded her the Lifetime Achievement Award for her remarkable achievements. The George and Joyce Wein Jazz & Heritage Center is an education and cultural center of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, the nonprofit that owns the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. It is a 12,000-square foot building that boasts seven music instruction classrooms for the Heritage School of Music, a recording studio, and a 200-seat auditorium. Additionally, a large collection of Louisiana art graces the walls of the center, creating an engaging environment for the educational and cultural activities in the building. The auditorium was designed by Oxford Acoustics. It can be adapted to multiple uses from concerts to theatrical productions to community forums and workshops. The room’s acoustics are diffusive and intimate, and it is equipped with high-definition projection, theatrical lighting and a full complement of backline equipment. -

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906)

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906) Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man, of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, and as a perfectionist he abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His best known work is the orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'apprenti sorcier), the fame of which became a matter of irritation to Dukas. In 2011, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians observed, "The popularity of L'apprenti sorcier and the exhilarating film version of it in Disney's Fantasia possibly hindered a fuller understanding of Dukas, as that single work is far better known than its composer." Among his other surviving works are the opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariadne and Bluebeard, 1897, later championed by Toscanini and Beecham), a symphony (1896), two substantial works for solo piano (Sonata, 1901, and Variations, 1902) and a sumptuous oriental ballet La Péri (1912). Described by the composer as a "poème dansé" it depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, coming across its guardian, the Péri (fairy). Because of the very quiet opening pages of the ballet score, the composer added a brief "Fanfare pour précéder La Peri" which gave the typically noisy audiences of the day time to settle in their seats before the work proper began. Today the prelude is a favorite among orchestral brass sections. At a time when French musicians were divided into conservative and progressive factions, Dukas adhered to neither but retained the admiration of both. -

From the Instructor

FROM THE INSTRUCTOR As any American schoolchild knows, Abraham Lincoln rose from his humble birth in a log cabin to lead the country through its violent Civil War and proclaim the emancipation of slaves. Most of us are less familiar, though, with America’s musical heritage. By exploring the overlapping terrain of these two seemingly unrelated fields, Lucas Lavoie’s final essay for WR 100 “Lincoln and His Legacy” comments simultaneously on Lincoln, America’s twentieth-century musical heritage, and what it means to be an American. In an exemplary synthesis of different disciplines—history, music, biography, political rhetoric—Lucas shows us how different genres can speak to one another and, if we listen carefully, to us, too. Moving beyond the facts of Lincoln’s remarkable life and times—subjects of the earlier writing in the course—this assignment asks students to trace the ways that later generations have used Lincoln’s legacy. Lucas’s discoveries in Mugar Library of several musical scores from the twentieth century initiated a deeper examination of the historical issues that prompted these compositions and their relevance to Lincoln’s speeches and writings. By analyzing and comparing works of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Vincent Persichetti, Lucas’s essay argues that these composers at critical moments in history used Lincoln in musical forms to demonstrate a shared ideal of American democracy. One important virtue to recognize in this essay is its deft command of the language for analyzing music. Even for those who may not be music scholars, Lucas’s clear explanations of musical examples allow readers to follow his points of comparison. -

~ the Bass Library Grand Opening

Architects'rendering of the study lounge and cafe space (Hammond, Beeby. Rupert, Ainge, Inc.,June 2005). ~ The Bass Library Grand Opening inal preparations are underway for the re-opening and new shelves in the Bass Library. All construction activity is expected renaming of the Cross Campus Library, scheduled for October to be completely fin ished for its official rededication on November Fof 2007. Installation of the oak millwork and the e1evarors, 30[h, 2007. among other final construction details, are now being completed. The renovation will feature several architectural highlights. A New furniture is being moved into open study areas as well as in the new stone pavilion entrance into the Bass Library is located on the group and individualized study rooms. To recognize the generous Cross Campus lawn between Woolsey Hall and Berkeley College support provided by Anne T. and Robert M. Bass '7[, the Library Nonh. The former interior space of the underground library will will open on October [9, 2007, as the BASS LIBRARY. Students be completely transformed, with vaulted ceilings, elegant steel and others in the Yale community will be able to use the beautifully mullions that define several glass windows and panitions, and redesigned spaces in the Bass Library after a midnight kick-off event a custom designed tile frieze echoing the woodwork, stone, and (see www.library.yale.edufordetails). New electronic classrooms will windows found in SML. A new occagonal stairwell, made from be available for instruC[ional sessions, and the library will stan hosting limestone and sandstone, with decorative carvings that complement a new service that emphasizes the use of technology and information the stonework that James Gamble Rogers originally used, has been resources for teaching and learning. -

Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years

BRANDING BRUSSELS MUSICALLY: COSMOPOLITANISM AND NATIONALISM IN THE INTERWAR YEARS Catherine A. Hughes A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Annegret Fauser Mark Evan Bonds Valérie Dufour John L. Nádas Chérie Rivers Ndaliko © 2015 Catherine A. Hughes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Catherine A. Hughes: Branding Brussels Musically: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in the Interwar Years (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) In Belgium, constructions of musical life in Brussels between the World Wars varied widely: some viewed the city as a major musical center, and others framed the city as a peripheral space to its larger neighbors. Both views, however, based the city’s identity on an intense interest in new foreign music, with works by Belgian composers taking a secondary importance. This modern and cosmopolitan concept of cultural achievement offered an alternative to the more traditional model of national identity as being built solely on creations by native artists sharing local traditions. Such a model eluded a country with competing ethnic groups: the Francophone Walloons in the south and the Flemish in the north. Openness to a wide variety of music became a hallmark of the capital’s cultural identity. As a result, the forces of Belgian cultural identity, patriotism, internationalism, interest in foreign culture, and conflicting views of modern music complicated the construction of Belgian cultural identity through music. By focusing on the work of the four central people in the network of organizers, patrons, and performers that sustained the art music culture in the Belgian capital, this dissertation challenges assumptions about construction of musical culture.