IRR March 2020 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Atomic Energy

DEPARTMENT OF ATOMIC ENERGY The vision of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) is to empower India through application of nuclear science and technology, and to provide better quality of life to its citizens. During the period from May, 2014 till December 31, 2014, the programmes of the Department achieved impressive growth in various segments and domains. These are described below. In Nuclear Power generation,Unit 1 of the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Project-1 (KKNPP-1) of 1000 MWe commenced commercial operation on December 31, 2014. With this, the total number of operating power reactors is 20 with an installed capacity of 5680MWe. The second Unit, KKNPP – 2 is also in advanced stage of commissioning. During the calendar year 2014 the highest ever generation of 37146 MUs was recorded which is 10% higher than last year's generation. The Rajasthan Atomic Power Station (RAPS)-5 recorded a continuous run of 765 days which is the best in Asia and the second best in the world. Consent of the Haryana State Pollution Control Board (HSPCB) was obtained in October 2014 to establish the Gorakhpur AnuVidyutPariyojanaHarayana (GHAVP) Units-1&2 (2x700 MWe PHWRs). In the area of uranium exploration, over 16,535 tonnes of additional Uranium Oxide (U3O8) reserves have been established in Andhra Pradesh, Meghalaya and Jharkhand during the year thus taking the country's uranium resources to over 2, 14,158 tonnes of U3O8. The Tummalapalle uranium project is readying for commissioning in 2015-16. The mine has achieved the desired ore production capacity and adequate ore has been stockpiled. -

Gandhi Heritage Portal

Case Study ® Gandhi Heritage Portal Client: Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Client Vertical: Govt./PSU Memorial Trust Project Type: Heritage Portal Technology Used: Drupal, MySQL Client Overview By considering the advantages of Drupal, Silver Touch has proposed developing custom modules About Client: The Ashram serves as a source for all functionalities such as photo gallery, video, of inspiration and guidance, and stands as a chronology, searching, and family tree. User monument to Gandhiji’s life mission and a testimony Management and Role Management come as an to others who have fought a similar struggle. It integral process of the application. Silver Touch also became home to the ideology that set India free. It proposed following 3rd party products / application … aided countless other nations and people in their 1. jPlayer extension for audio gallery own battles against oppressive forces. 2. Book Reader extension for displaying books and The Ashram is presently involved in a number volumes related to Gandhiji’s life on the web portal of activities that serves to both preserve the 3. Google Map integration that displays the places history of Gandhi and the freedom struggle and visited by Gandhiji around world also to promote and educate people in the great 4. Google Analytics integrates for displaying reports philosophies, values and teachings of Gandhi. on backend. The Ashram Trust funds activities that include education for the visitor, the community and routine Requirement Overview: maintenance of the museum and its surrounding Client wanted to develop a web portal in the memory grounds. of Mahatma Gandhi and to present his Heritage on web. -

Mahatma Gandhi, an Inspiration to Successive Generations- Arun Jaitley Minister Launches Electronic Version of the Collected Wo

Mahatma Gandhi, an inspiration to Successive Generations- Arun Jaitley Minister launches Electronic version of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi The Hindi version of CWMG (Sampoorna Gandhi Vangmaya) to be digitized soon Shri Arun Jaitley, Minister for Finance, Corporate Affairs & Information and Broadcasting today launched the electronic version of “The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi”, a monumental document of Gandhiji’s words as he spoke and wrote, day after day beginning from 1884 till 30 th January 1948 at Gandhi Peace Foundation. The Minister also uplinked the e-version on the Gandhi Heritage Portal, a comprehensive repository of authentic Gandhiana. The portal hosts e-CWMG in a searchable pdf format to ensure easy and free accessibility of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi for people across the world. On the occasion, Shri Jaitley also announced that the Hindi version of the monumental work CWMG (Sampoorna Gandhi Vangmaya) would be digitized soon. Minister of State (I&B), Col. Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore, Secretary (I&B), Shri Sunil Arora and Members of the Expert Committee were present on the occasion. Speaking on the occasion, Shri Jaitley said the intrinsic and heritage value of the e-CWMG Project had the collaboration and partnership of institutions that have been founded and nurtured by Gandhiji himself. Shri Jaitley said that this digitized version of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi would be instrumental in preserving the valuable national heritage and disseminating it for all humankind. Shri Jaitley also mentioned that the Mahatma was a true visionary, whose thought process had touched various facets of human life. -

E-Version of Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi Launched

VOL. XL NO. 25 PAGES 32 NEW DELHI 19 - 25 SEPTEMBER 2015 ` 8.00 STRESS MANAGEMENT FOR YOUTH Dr. Jitendra Nagpal tress is a non-specific response of the body to a lack of mobility/transport for high risk patients at the S demand. Researchers define stress as physical, health facility, poor communication with co-workers, lack mental or emotional response to events that cause bod- of support from supervisor, no forum to express work ily or mental tension. Stress arises when individuals per- concerns and issues and lack of resources to support ceive that they can adequately cope with the demands the provision of care. being made on them or with threats made to their well Physiological stressors are situations and circum- being. For instance, for a teacher, stress is "the experi- stances that affect our body. Examples of physiological ence by teacher of unpleasant, negative emotions, such stressors include rapid growth of adolescence, as anger, anxiety, tension, frustration or depression, menopause, illness, aging, giving birth, accidents, lack resulting from some aspect of their work as a teacher". It of exercise, poor nutrition, and sleep disturbances. is important to understand that while stress is necessary Thoughts: Our brain interprets and perceives situations and positive, it can also be negative and harmful. as stressful, difficult, painful, or pleasant. Some situa- Whether positive or negative, physical or mental, the tions in life are stress provoking, but it is our thoughts body's reaction to stress can be described by three that determine whether they are a problem for us or not. -

Gandhi: a Player of Infinite Games

TIF - Gandhi: A Player of Infinite Games VINAY LAL October 4, 2019 Photos courtesy: Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust and Gandhi Heritage Portal Even radical dissenters have experimented within some boundaries. Gandhi played with boundaries themselves in nearly every domain of life — politics, sexuality, culture, knowledge. He was uniquely a player of infinite games with a vision of life as play. The African American activist, Bayard Rustin, is acknowledged by scholars as one of the principal figures in the Civil Rights Movement of the United States and the chief architect of the famous March on Washington in 1963 where Martin Luther King, Jr. mesmerised the large gathering with his “I Have a Dream” speech, an oracular demonstration of his rhetorical gifts. Lesser known, at least to the general public, is the fact that Rustin was a lifelong student of the life and work of Gandhi who had a large hand in shaping King’s understanding of satyagraha and bringing nearly the entire arsenal of Gandhian ideas of mass nonviolent resistance to the fore in the struggle for civil and political rights. His most prominent biographer, John D’Emilio, says unhesitatingly that “more than anyone else, Rustin brought the message and methods of Gandhi to the United States.” Rustin’s eyes were turned upon the anti-colonial struggle in India and he was firmly of the view that “no situation in America has created so much interest among negroes as the Gandhian proposals for India’s freedom.” King was but a schoolboy when Rustin had already established a reputation as a “one-man nonviolent army” working on behalf of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), an international religious organisation that advocated radical pacifism and that in the US sought a distinctive and revolutionary approach to the race problem. -

Ministry of Culture 1. 100 Adarsh Monuments Adarsh Monuments

Ministry of Culture 1. 100 Adarsh Monuments ● Adarsh Monuments were identified in State of Assam, Bihar, Delhi, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, J&K, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal. The scheme was launched on 26th December, 2014 for providing improved visitor amenities, especially for the physically challenged, besides cleanliness, drinking water, and interpretation centres, cafeteria, souvenir shop, wi-fi, garbage disposal etc. The civic amenities are being augmented at these sites. ● 25 ASI sites were launched as “Adarsh Smarak” on 26th December, 2014.(List of 25 Adarsh Monuments at Annexure 1). ● 75 more Adarsh Monuments protected by ASI have been identified and included in the list of “Adarsh Smarak” and the same are also being included in ‘Swachh Paryatan Mobile App’ launched by the Ministry of Tourism. With this a total of 100 Monuments protected by ASI are being developed and maintained as Adarsh Monuments. (List of 75 Adarsh Monuments at Annexure 2). 2. ‘Swachh Bharat- Swachh Smarak’ ● The ASI has ranked top 25 Adarsh Monuments on the basis of Cleanliness parameters such as amenities like toilets, green lawns, Polythene Free Zone, signage for awareness, disabilities access, drinking water and provision for garbage bins etc. ● “Rani ki Vav (Gujarat)” a World Heritage Site has been awarded as the cleanest iconic place in the country. ● The Ministry also observed a Swachhta Pakhwada from 16th to 30th September, 2016 to spread awareness about the need and importance of cleanliness in all the domains. M/o of Culture and its various organizations have made all possible efforts for an efficient observance of the Swachhta Pakhwada. -

© 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust

5/15/2018 Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 1/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 2/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 3/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 4/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 5/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 6/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 7/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Vol II 8/22 5/15/2018 © 2018 Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust Gandhi Heritage Portal Key Texts of Mahatma Gandhi: -

Sonam Wangchuk

1 Resolution Published in 2019 by New Acropolis Cultural Organization. Mumbai, India. http://www.empoweringrealchange.com/ www.acropolis.org.in [email protected] Copyright © New Acropolis Cultural Organization 2019. All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing by the publisher. Printed in India. Resolution New Acropolis Cultural Organization is an independent We have always tried to understand the expression of all member of an International non-profit association (IONA), cultures, past and present, to discover the roots of their represented in over 60 countries across the world. works of art, scientific advances, religious experiences and social and human projects through Philosophy, Culture and IONA promotes an ideal of timeless values to contribute to Volunteering. With inspiration from the timeless principles individual and collective evolution. Its associative structure of the Indian tradition, New Acropolis India, works with a guarantees respect for the diversity, autonomy and initiative specific focus to rediscover India’s rich artistic, scientific of each of its member associations. Its operational structure and human heritage and offer it as a vital contribution to enables it to act independently of all political, religious or collective human progress relevant to our times today. financial interests. Philosophy, when it is practical, is educational. It helps us to know ourselves and to improve ourselves. To be a philosopher is a way of life committed to the best aspirations of humanity. -

Engaging with the Mahatma: Multiple Perspectives

Engaging with the Mahatma: Multiple Perspectives The Gandhian Studies Centre Dr. Bhanuben Mahendra Nanavati College of Home Science Engaging with the Mahatma: Multiple Perspectives Edited By Dr. (Prof.) Mala Pandurang Mrs. Vidya Subramanian Ms. Huda Sayyed Ms. Jinal Baxi Cover Designed By D‘dsign Graphics Printed By Mahavir Printers, Mumbai 400075 Published By Seva Mandal Education Society‘s Dr. Bhanuben Mahendra Nanavati College of Home Science NAAC Reaccredited Grade ‗A+‘ with CGPA 3.69/4 UGC Status: College with Potential for Excellence (CPE) Maharishi Dhondo Keshav Karve Best College Awardee Smt Parameshwari Devi Gordhandas Garodia Educational Complex, 338, R.A Kidwai Road. Matunga, Mumbai 2020 ISBN 978-93-5258-741-3 CONTENTS About the Centre ………………………………………. i Introduction …………………………………………… iv 1. Sabhi Log Apne Jan 1 Dr. Ramdas Bhatkal ……………………………. 2. Gandhi in Central and Eastern Europe 3 Dr. Roxana-Elisabeta Marinescu ………… ……. 3. Gandhi - of the Earth, Earthy 16 Dr. Betty Govinden .……………………………… 4. Gandhi: A Making of a Mahatma 35 Dr. Preeti Shirodkar ………..…………………… 5. Relevance and Significance of Gandhian 50 Thoughts for Women in the Contemporary World Dr. Vibhuti Patel ………………………………... 6. Why now? Hey Ram! (Gandhi 2019 and the New 62 Graffiti on an already bleeding tombstone) Dr. Sridhar Rajeswaran ………………………… 7. Close to the Mahatma 73 Mr. Pheroze Nowrojee …………………………. 8. Gandhi‘s Earth and Other Poems 78 Dr. Betty Govinden ……………………………... Collected Annotations ………………………………. 82 List of Books at the Gandhian Studies Center……… 96 The Gandhian Studies Centre The University Grants Commission recognized Gandhian Studies Centre was established in 2013 at Dr. BMN College of Home Science. The primary objective of the centre is to create an understanding and appreciation of Gandhian philosophy among the youth of today. -

Notes of Guha on Gandhi Annotated

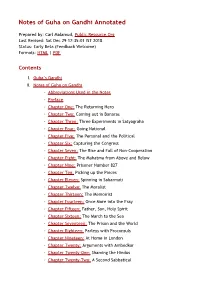

Notes of Guha on Gandhi Annotated Prepared by: Carl Malamud, Public.Resource.Org Last Revised: Sat Dec 29 17:35:01 IST 2018 Status: Early Beta (Feedback Welcome) Formats: HTML | PDF Contents I. Guha’s Gandhi II. Notes of Guha on Gandhi ◦ Abbreviations Used in the Notes ◦ Preface ◦ Chapter One: The Returning Hero ◦ Chapter Two: Coming out in Banaras ◦ Chapter Three: Three Experiments in Satyagraha ◦ Chapter Four: Going National ◦ Chapter Five: The Personal and the Political ◦ Chapter Six: Capturing the Congress ◦ Chapter Seven: The Rise and Fall of Non-Cooperation ◦ Chapter Eight: The Mahatma from Above and Below ◦ Chapter Nine: Prisoner Number 827 ◦ Chapter Ten: Picking up the Pieces ◦ Chapter Eleven: Spinning in Sabarmati ◦ Chapter Twelve: The Moralist ◦ Chapter Thirteen: The Memoirist ◦ Chapter Fourteen: Once More into the Fray ◦ Chapter Fifteen: Father, Son, Holy Spirit ◦ Chapter Sixteen: The March to the Sea ◦ Chapter Seventeen: The Prison and the World ◦ Chapter Eighteen: Parleys with Proconsuls ◦ Chapter Nineteen: At Home in London ◦ Chapter Twenty: Arguments with Ambedkar ◦ Chapter Twenty-One: Shaming the Hindus ◦ Chapter Twenty-Two: A Second Sabbatical Notes of Guha on Gandhi Annotated ◦ Chapter Twenty-Three: From Rebels to Rulers ◦ Chapter Twenty-Four: The World Within, and Without ◦ Chapter Twenty-Five: (Re)capturing the Congress ◦ Chapter Twenty-Six: One Nation, or Two? ◦ Chapter Twenty-Seven: Pilgrimages to Gandhi ◦ Chapter Twenty-Eight: Somewhere between Conflict and Cooperation ◦ Chapter Twenty-Nine: Towards ‛Quit India’ ◦ Chapter Thirty: A Bereavement and a Fast ◦ Chapter Thirty-One: The Death of Kasturba ◦ Chapter Thirty-Two: Picking up the Pieces (Again) ◦ Chapter Thirty-Three: Prelude to Partition ◦ Chapter Thirty-Four: Marching for Peace ◦ Chapter Thirty-Five: The Strangest Experiment ◦ Chapter Thirty-Six: Independence and Division ◦ Chapter Thirty-Seven: The Greatest Fasts ◦ Chapter Thirty-Eight: Martyrdom ◦ Epilogue: Gandhi in Our Time III. -

An Aesthetic Cartography of Fast : Gandhi and The

Universität Potsdam Kunst und Medien Vergleichende Literatur- und Kunstwissenschaft Masterarbeit Prof. Johannes Ungelenk & Prof. Dirk Wiemann SoSe 2019 An Aesthetic Cartography of Fast: Gandhi and the Hunger Artists Brigard Torres, Juan Camilo MA Vergleichende Literatur- und Kunstwissenschaft This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License: Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International. This does not apply to quoted content from other authors. To view a copy of this license visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Published online in the Institutional Repository of the University of Potsdam: https://doi.org/10.25932/publishup-46933 https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-469333 1 Index Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 1. An aesthetic cartography of active hunger 4 2. Fasting in Gandhi's philosophy and history 11 2.1. Self-control, duty, brahmacharya, diet, satyagraha, ahimsa and fasting 11 2.2. A brief history and teleology of Gandhi’s political fasts 20 3. An aesthetic cartography of the performative of Gandhi’s fasts 25 3. 1. Mediality: holding fast to the weapon of publicity 25 3.1.1. Press 26 3.1.2. Photography 31 3.1.3. Newsreels 33 3.1.4. Film documentary 35 3.2. The materiality of Gandhi’s fasts 37 3.2.1. Corporeality 37 3.2.1.1. Dressed with ideas 37 3.2.1.2. Embodying ideas 39 3.2.1.3. A speech in whispers 43 3.2.2. Space and time 45 3.2.2.1. Temporality: Assisting the loved one in need or the endurance test 45 3.2.2.2. -

Sanitation: a Purification Process

Sanitation: A Purification Process Sudarshun Iyengar i i our years earlier, paying towards SwachhHindus tan. tribute to the Father of the Nation Mahatma Gandhiji's ldea of Swachh Gandhi, the fifteenth Hindustan Prime Minister of India There is considerably more to in his first Independence Gandhiji's idea of a Sw achh Hindus tan Day speech on August 15, 2074, said than building toilets and making it free the following from the ramparts of from open defecation free, although ffi*ffGELSB*JTTF{S the Red Forl. ?Hg ltjtl{AY!'ljt it is the first and very important step. Brothers and sisters, it will be Gandhiji wanted to see Hindustan 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Swachh- clean and cleansed, body Gandhi tn 2019... Mahatma Gandhi and soul. He was distressed about had cleanliness and sanitation closest the way we lived and maintained our to his heart. I, therefore, have to inhabitations. Gandhiji felt deeply hurt #*m #fa dgd sre sp'gpdscre{d launch a 'clean India'campaign from the way we all treated communities gi#s.sssf#J fepgr*ar, 2nd October this year and carry it who were condemned to handle filth forward in 4 years. I want to make a and human excreta. Gandhiji also vdff*xgr sred fsp{;s6 beginning today itself and that is - all realised that Indians had, over time, schools in the country should have developed a very unscientific attitude scas*s$sdd#ss {$-q' toilets with separate toilets for girls. towards sanitation and hygiene. It was # r{}Fr,}trr'wttive Only then our daughters will not be this attitude that was responsible for compelled to leave schools midway.l creating a class of people who were pF"#grglg$p3€9.