Choice of Law in Contracts: Some Thoughts on the Weintraub Approach Aaron Twerski Brooklyn Law School, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHABBAT, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 - ADAR 4, 5780 PARSHAT TERUMAH (Pg

SHABBAT, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 - ADAR 4, 5780 PARSHAT TERUMAH (Pg. 444) TORAH INSIGHTS FROM RABBI ELI BABICH The Torah states that the walls of the Tabernacle (Mishkan) were made of large planks of acacia wood (Terumah 26:15). Construction of the Tabernacle commenced while the Jewish people were in the desert. As an abundance of wood is not natural in desert conditions, one can ask how the nation procured such large quantities of wood needed to con- struct the Tabernacle. Rashi commented, Our patriarch, Jacob, planted cedars in Egypt, and when he was dying, he commanded his sons to bring them up with them when they left Egypt. He told them that the Holy One, blessed is He, was destined to command them to make a Mishkan of acacia wood in the desert. In anticipation of the ultimate redemption, upon arrival in Egypt, Jacob ordered the planting of trees for the eventual use in the construction of the Tabernacle. Rabbi Yaakov Kaminetsky (1891- 1986) questioned the necessity of Jacob arranging for the planting of trees, as surely there were suitable trees in Egypt. Rabbi Kaminetsky suggested that Jacob planted the trees for psychological reasons. These trees served as a reminder that the enslaved Jewish people would one day be redeemed. Even though the promise of redemp- tion was widely known, the trees served as a tangible reminder, each and every day, of the ultimate salvation of the Jewish people. The nation routinely encountered these trees during their years of slavery, and for the nation, the trees were a physical symbol of hope. -

J. David Bleich, Ph.D., Dr. Iuris Rosh Yeshivah (Professor of Talmud)

J. David Bleich, Ph.D., Dr. Iuris Rosh Yeshivah (Professor of Talmud) and Rosh Kollel, Kollel le-Hora'ah (Director, Postgraduate Institute for Jurisprudence and Family Law), Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary; Professor of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; Tenzer Professor of Jewish Law and Ethics, Yeshiva University; Rabbi, The Yorkville Synagogue, New York City; has taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Hunter College, Rutgers University and Bar Ilan University; ordained, Mesivta Torah Vodaath; Graduate Talmudic Studies, Beth Medrash Elyon, Monsey, N.Y. and Kollel Kodshim of Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim of Radun; Yadin Yadin ordination; Woodrow Wilson Fellow; Post-Doctoral Fellow, Hastings Institute for Ethics, Society and the Life Sciences; Visiting Scholar, Oxford Center for Post-Graduate Hebrew Studies; Editor, Halakhah Department, Tradition; Contributing Editor, Sh'ma; Associate Editor, Cancer Investigation; Past Chairman, Committee on Medical Ethics, Federation of Jewish Philanthropies; Founding Chairman, Section on Jewish Law, Association of American Law Schools; Contributor, Encyclopedia of Bioethics; Fellow, Academy of Jewish Philosophy; Member, New York State Task Force on Life and the Law; Past Chairman, Committee on Law, Rabbinical Alliance of America; Member, Executive Board, COLPA (National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs); Member, Board of Directors, Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America; Member, National Academic Advisory Council of the Academy for Jewish Studies Without Walls; Member, -

BSERVER in This Issue

THE JEWISH BSERVER in this issue "Did You Conduct Your Business With Faith?" Rabbi Avrohom Pam ............................................................................. 3 Bombing Auschwitz - a footnote to Jewish history Lewis Brenner ........................................................................................ 8 A Letter of Guidance for These Troubled Times Rabbi Eliezer Schach ............................................................................12 Reb Reuvain Grozovsky l"!:i,:i7 i'',l.' ,:ii - 20 Years After His Passing, Nisson Wolpin ............................... 15 Teaching The Fourth Son, Helene Ribowsky ......................................... 23 "The Stone Rejected By The Builders", Hanoch Te/ler ....................... 25 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July Books In Review, Aryeh Kaplan and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, The Jews of Rhodes ........................................................................... 31 New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, Second Looks at the Jewish Scene N.Y. Subscription: $7.50 per year; "Holocaust" - At Least They Know ............................................. 33 two years, $13.00; three years, $18.00; outside of the United Jewish History With A Twist ............................................................ 35 States, $8.50 per year. Single copy, Mazel Tov at the Orange Bowl (or "Thank G-d Ifs one dollar. Printed in the U.S.A. Not My Mendel!") ................................................................. -

Download Catalog

INTRODUCTION Ohr Somayach-Monsey was originally established in 1979 as a branch of the Jerusalem-based Ohr Somayach Institutions network. Ohr Somayach-Monsey became an independent Yeshiva catering to Ba’alei Teshuvah in 1983. Ohr Somayach-Monsey endeavors to offer its students a conducive environment for personal and intellectual growth through a carefully designed program of Talmudic, ethical and philosophical studies. An exciting and challenging program is geared to developing the students' skills and a full appreciation of an authentic Jewish approach to living. The basic goal of this vigorous academic program is to develop intellectually sophisticated Talmudic scholars who can make a significant contribution to their communities both as teachers and experts in Jewish law; and as knowledgeable lay citizens. Students are selected on a basis of membership in Jewish faith. Ohr Somayach does not discriminate against applicants and students on the basis of race, color, national or ethnic origin provided that they members of the above mentioned denomination. CAMPUS AND FACILITIES Ohr Somayach is located at 244 Route 306 in Monsey, N.Y., a vibrant suburban community 35 miles northwest of New York City. The spacious wooded grounds include a central academic building with a large lecture hall and classrooms and a central administration building. -1- There are dormitory facilities on campus as well as off campus student housing. Three meals a day are served at the school. A full range of student services is provided including tutoring and personal counseling. Monsey is well known as a well developed Jewish community. World famous Talmudical scholars as well as Rabbinical sages in the community are available for personal consultation and discussion. -

2020 - 202 1577 48Th St

RC BYBZ Brooklyn, NY 11219 NY Brooklyn, 48th1577 St. Rabbinical College Bobover Yeshiva Bnei Zion Yeshiva Bobover Rabbinical College Bnei Zion Yeshiva Bobover College Rabbinical Rabbinical College RC Bobover Yeshiva BYBZ Bnei Zion 1577 48th St. • Brooklyn, NY 11219 phone 718-438-2018 Fax 718-871-9031 2020 - 2021 CATALOG 20 20 - 20 2 1 C ATALOG "What distinguishes man from all other creatures is his ability to think, to know, to comprehend, to reason. To the extent that he develops these qualities and refines his wisdom, he fulfills his purpose, deepens his humanity and enriches society." Rabbi Solomon Halberstam Admor of Bobov 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ....................................................................................................... 11 ACCREDITATION........................................................................................ 11 NOTICE OF NON-DISCRIMINATION ..................................................... 12 DISCLAIMER OF PLACEMENT ................................................................ 12 CORONA - COVID-19 ................................................................................... 12 MISSION AND PURPOSE ........................................................................... 13 STUDENT RIGHT-TO-KNOW DISCLOSURES ........................................ 14 OFFICERS OF THE COLLEGE .................................................................. 16 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS .................................................................. 16 ACADEMIC CALENDAR ............................................................................ -

Rosh Yeshiva Ofyeshiva Beis Yeshiva's Growth -From Erection Ofthe Ner Tihatalmud of Bensonhurst, Rabbi II

o Yes, I want to help build Torah homes and own my 'fj)~{f~ own home In any Torah community. 'if)~ 'ifJtd$ I'm takingadvantageotthespeciaJpreviewprice: 0 I for $125 0 2 for $550 [J 5 fOr $1,000 Decetnber 30, 2005 Ooops, I missed the Nm>ember 24th deadline: 0 I for $360 C'J 2 for $600 rJ 4 for $l,000 Sth Day Of Chftnukah 0 Please mahe my payment payable in 4 installments. Note: pre-pa,vment & credit rants only t#ll~~\iitt;/ 0 ENCWSED IS Ml' CONTRIBUTION OF PAYMENI' [J PLEASfl CHARGE. MY CREDIT CARD 0' MC, 0 VlSA 0 A.MEX CARD#: -----------------------EXP DATll _____~-- S1<'.<NATt.tltll --... ·--"·--· --·--------- - -- -- ----- -------·------ ------------ -----··-----·--·----·---- I THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021-6615 IS PUBLISHED MONTHl.Y EXCEPT Jrn.Y & AUGIJST BY IN THIS ISSUE ... THE AGUOATH IS!lAEL OF AMERICA 42 BROADWAY. NEW YORK, NY 10oo4. PERIODICALS POSTAGE PAID IN NEW YORJ(, NY. SUBSCRIPTION S25.00/YEAR; 6 NOTED IN SORROW 2 YEARS, $46.00; 3 YEARS, S69.oo. 01JTSll)E OF THE lJNITEO STATES (US MINOS DRAWN ON A lJS BANK 7 READERS REACT •.. AUTHORS RESPOND ONLY) $15.00 SURC11ARGE PER YEAR. SINGLE COPY SJ.so: 0UTSIOr-: NY AREA S3.95; FOREIGN $4.50. 16 RABBI ABBA BERMAN ?··'11, an appreciation by POSTMASTER: Binyomin Wolpin SEND AIJDRESS CHANGES TO: THE JEWJSll OBSERVER 42 fil{OADWAY, NY. NY T0004 23 A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH ... TEL 2.Hil-797-9000, t'AX 646-254.-1600 PRINTED IN THE l!SA FOR MECHANCHIM, Rabbi Label Steinhardt RABBI N1sSON WOL!'IN, f:ditor 27 IGNITING A SPARK FOR MEANINGFUL TEFILLA, f-:ditorial /Joan! RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS, Chnlrman a review article by Rabbi Labish Becl<er RABBI ABBA BRUONY JOSEP!i FIUEDENSON 31 NOTES ON BORCHI NAFSHI, Yisrael Rutman R.o\Bl:U YISl~OEI. -

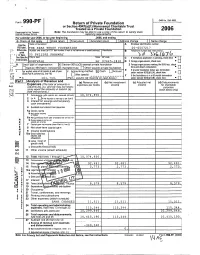

Return of Private Foundation

OMB No 1545 0052 Form 990 -PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2006 Department of the Treasury Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2006 , or tax year be g innin g , 2006 , and endin g G Check all that apply Initial return Final return Amended return Address change Name change Use the Name of foundation A Employer Identification number IRS label , THE EZRA TRUST FOUNDATION 20-6557217 Otherwise, Number and street (or P 0 box number i t ma i l is not del ivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) print t^1 S) v ,i or type . 25 PHILIPS PARKWAY v See Specific City or town State ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions . MONTVALE NJ 07 64 5-1810 D 1 Foreign organizations , check here •H Check type of organization X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation here and attach computation value of all assets at end of year Accounting method Cash Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated Fair market J X under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) Other (specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60- month termination under section 507(b)( 1 )(B), check here c.; $ 101, 743. -

RHETORIC of MODERN JEWISH ETHICS by Jonathan Kadane Crane a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the Requirements for the Degree

RHETORIC OF MODERN JEWISH ETHICS by Jonathan Kadane Crane A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Religion University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan Kadane Crane (2009) Rhetoric of Modern Jewish Ethics Jonathan Kadane Crane Ph.D. Graduate Department of Religion University of Toronto 2009 Abstract Jewish ethicists face a twofold task of persuading audiences that (a) their proposal for an issue of social concern and justice is the right and good thing to do, and (b) their proposal fits within the Judaic tradition writ large. Whereas most scholarship in the field focuses on how Jewish ethicists argue by dividing arguments into halakhic formalist, covenantalist and narrativist categories, these efforts fail both to reflect the diverse ways ethicists actually argue and to explain why they argue in these ways. My project proposes a new methodology to understand how and why Jewish ethicists argue as they do on issues of justice and concern. My project combines philosophical theology and discourse analysis. The first examines an ethicist’s notion of covenant ( brit ) in light of theories found in the Jewish textual tradition. Clarifying an ethicist’s notion of covenant uncovers that person’s assumptions about the scope and binding nature of elements in the Judaic tradition, and that person’s conception of an audience’s responsibilities to the normative argument s/he articulates. Certain themes come to the fore for each ethicist that, when mapped, reveal striking relationships between an ethicist’s notion of covenant and anticipated ethical rhetoric. These maps begin to show why certain ethicists argue as they do. -

UNITED STATES of AMERICA Looted Judaica and Judaica With

224 Country Name: UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Looted Judaica and Judaica with Provenance Gaps in Country Yes. Existing Yes. Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal (NEPIP). Projects Overview Looted Source: Cultural (1) Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal; http://www.nepip.org, last accessed Property on June 2014. Databases (2) Email correspondence with Brooke Leonard, Assistant Manager, Museums & Community Collaborations Abroad, AAM on March 30, 2012. The Nazi-Era Provenance Internet Portal (NEPIP) lists 19 museums (as of March 2014) that note holding Judaica with provenance gaps in their collections. These museums are: Ackland Art Museum, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Chrysler Museum of Art, Cincinnati Art Museum, Hillwood Museum and Gardens, Hood Museum of Art, Indiana University Art Museum, The Jewish Museum, Judaica Museum of the Hebrew Home at Riverdale, Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Mizel Museum, Museum of Art (Rhode Island School of Design), Museum of Fine Arts Houston, North Carolina Museum of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Spencer Museum of Art, Spurlock Museum, Toledo Museum of Art; (Please note that the number of museums that provide information on their Judaica collection has not changed in the last couple of years.) It is, however, not possible to view the individual Judaica items on NEPIP. The museums only provide a general listing of all art objects that have provenance gaps. A Claims Conference review of Judaica objects posted by U.S. museums on NEPIP, conducted in April 2012, revealed that only 128 Judaica objects with provenance gaps are in fact listed on NEPIP. Considering the otherwise large number of total objects posted (as of April 2012, there were 28,733 objects), this accounts for a rather small percentage: 0.4%. -

Rabbi Aaron D. Twerski, Marquette Lawyer and Hofstra Dean Table of Contents Marquette University

MarquetteMarquette LawyerLawyer Fall 2005/Winter 2006 Marquette University Law Alumni Magazine Rabbi Aaron D. Twerski, Marquette Lawyer and Hofstra Dean table of contents Marquette University Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J. Marquette Lawyer President Madeline Wake 3 dean’s column Provost features Gregory J. Kliebhan Senior Vice President 4 marquette lawyer at the helm of hofstra 8 sgt. mick gall—citizen-soldier Marquette University Law School 11 marquette lawyers once removed Joseph D. Kearney Dean and Professor of Law law school news [email protected] (414) 288-1955 15 vita with vada Peter K. Rofes 16 admissions report Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor of Law 18 sba president leads the way Christine Wilczynski-Vogel 19 moot court champions Assistant Dean for External Affairs [email protected] 20 commencement of 2005 graduates Bonnie M. Thomson Associate Dean for Administration alumni news and class notes Paul D. Katzman 25 alumni association Assistant Dean for Career Planning 27 from the dean’s mailbag Sean P. Reilly Assistant Dean for Admissions 28 law school alumni awards Jane Eddy Casper marquette joins the big east Assistant Director of Part-Time Legal 38 Education and Assistant to the Dean for Special Projects 41 alumni notes speeches Marquette Lawyer is published by Marquette Law School. 56 orientation remarks of genyne edwards Please send address changes to: Marquette Law School 60 “make justice your aim (Is. 1:17)”— Office of Alumni Relations law review banquet remarks Sensenbrenner Hall of reverend paul b. r. hartmann P.O. Box 1881 Milwaukee, WI 53201-1881 65 “the american belief in a rule of law in global context”—professor papke’s Phone: (414) 288-7090 remarks at the korea military academy Law School Fax: (414) 288-6403 http://law.marquette.edu 69 dean kearney’s remarks at 24th annual st. -

Form 990-PF 2006

OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(aXl) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2006 Department of the Treasury Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2006, or tax year beginning , 2006, and ending 0 G Check all that apply: Initial return Final return Amended return Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS label . YES BEN DOVID FOUNDATION , INC 13-4120047 Otherwise, Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) print or type. 25 PHILIPS PARKWAY (201) 326-1676 See Specific City or town State ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions. MONTVALE NJ 07645-1810 D 1 Foreign organizations, check here H Check type of organization: Lf Section 501 (c)(3exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q Section 4947(a) (1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method, X Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here q (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) q Other (specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination under section 507(b)(1XB), check here ► $ -28 , 191. -

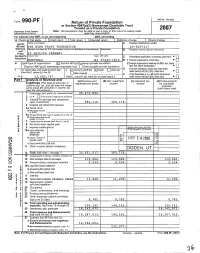

Form 990- P F 2007

,G OMB No 1545 0052 Form 990- P F Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2007 Department of the Treasury Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state Internal Revenue Service reporting requirements For calendar year 2007, or tax year beginnin g , 2007 , and ending G Check all that apply. Initial return Final return Amended return Address change r Name change Use the Name of foundation A Employer identificabon number IRS label. THE EZRA TRUST FOUNDATION 20-6557217 Otherwise, Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see the instructions) print or type. 25 PHILIPS PARKWAY See Specific City or town state ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions . MONTVALE NJ 07645-1810 D 1 Foreign organizations, check here H Check type of organization X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q Section 4947(a)(1 ) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method X Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part II, column (c), fine 16) 11 Other (s pecify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 12 , 665 , 747.