50 Minute-By-Minute Football Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P18 3 Layout 1

THURSDAY, JANUARY 8, 2015 SPORTS Former FIFA ref slams Premier League officials LONDON: The standards of some Cup final as well as matches in the who himself was on the receiving end “I was with a group of FIFA referees Hackett said of the referees. “At the Premier League referees were “bor- European Championship and Olympic of a reckless challenge,” he said. from Nigeria who watched with moment, these guys are performing dering on appalling” during matches Games in 1988, said on his blog “You “It is unbelievable that a so-called amazement. Do you think I took joy in well below the level.” over the busy holiday period, accord- Are The Ref” he counted “over 20 top referee should make such a mis- that?” Marriner is one of the five refer- However, PGMOL countered that ing to former FIFA referee Keith major errors” during the Christmas take. “I see standards falling. Over the ees identified by Hackett who should the accuracy of decision-making by Hackett, who has named five referees period. Christmas period, it reached stan- no longer officiate Premier League referees in the Premier League was he claims should be dropped. He cited the “stupid” red card dards that were bordering on matches after the end of this season. currently at an all-time high. Their fig- The organisation that controls the shown to Swansea City’s Wayne appalling.” He continued: “There was a As well as Marriner he named Mike ures say accuracy on major decisions referees, Professional Game Match Routledge at Queens Park Rangers by pretty poor performance from Andre Jones, Lee Mason, Chris Foy and Lee was up to 95 percent from 94.1 per- Officials Limited (PGMOL) has reject- Anthony Taylor on New Year’s Day and Marriner in the Manchester City v Probert, who refereed last season’s FA cent, accuracy on decisions in the ed Hackett’s claims, saying standards which has since been overturned, as Everton game (on Dec. -

ENGLAND - SWEDEN MATCH PRESS KIT Gamla Ullevi, Gothenburg Friday 26 June 2009 - 18.00CET (18.00 Local Time) Matchday 4 - Semi-Finals

ENGLAND - SWEDEN MATCH PRESS KIT Gamla Ullevi, Gothenburg Friday 26 June 2009 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Matchday 4 - Semi-finals Contents 1 - Match background 6 - Head coach 2 - Team facts 7 - Competition facts 3 - Squad list 8 - Competition information 4 - Group statistics 9 - Tournament schedule 5 - Match officials 10 - Legend Match background Both England and Sweden will be attempting to end a long wait for international success when they meet in Gothenburg in the first semi-final of the 2009 UEFA European Under-21 Championship. • England claimed the last of their two U21 titles 25 years ago, defeating Spain 3-0 on aggregate over two legs in the 1984 final. The years since have largely been barren, with no title at any since a side including Paul Scholes, Gary Neville, Sol Campbell and Robbie Fowler triumphed on home soil in the European U18 Championship in 1993. This time round hopes are high following wins against Finland (2-1) and Spain (2-0), coupled with a 1-1 draw against Germany, taking Stuart Pearce's side through as Group B winners to face Sweden. They will hope to fare better than two years ago when they went out to the Dutch hosts after a 32-penalty shoot-out. • Sweden, meanwhile, have never won a UEFA men's competition, losing to Italy 2-1 on aggregate over two legs off the 1992 U21 final. The Scandinavian side last reached this stage five years ago, losing on penalties to Serbia and Montenegro in Oberhausen after a 1-1 draw. A measure of revenge was exacted on Matchday 3 of this competition, a 3-1 win against Serbia in Malmo taking the hosts into the last four as Group A runners-up following a 5-1 win against Belarus and 2-1 defeat by Italy. -

Gulf Times Sport

RUGBY | Page 10 CRICKET | Page 5 England stay Zimbabwe To Advertise here Call: 444 11 300, 444 66 621 on course for ousted by Six Nations Afghanistan Grand Slam in World T20 Sunday, March 13, 2016 FOOTBALL Jumada II 4, 1437 AH Messi masterclass GULF TIMES as Barcelona hit Getafe for six SPORT Page 3 SPOTLIGHT BASKETBALL FOOTBALL/FA CUP Schumi manager Rembert Lukaku on avoids target twice giving detailed shines as as Everton updates Khor bounce sink Chelsea back for win El Jaish hold nerve to edge Al Arabi 81-77 Michael Schumacher suff ered a serious skiing accident in 2013 and is undergoing treatment in Switzerland. AFP Berlin ichael Schumacher’s manager Sabine Kehm admits purposefully avoiding giving out Mexact details about the health of Germany’s Formula One legend to prevent speculation or misinter- pretation in the media. “At the moment, I see no alter- native,” she told yesterday’s edi- tion of the Munich-based news- paper the Sueddeutsche Zeitung. “Every sentence is a catalyst for new inquiries, every word is a beacon for further information. It never dies down.” Former seven-time world champion Schumacher suff ered head injuries in a skiing accident Everton’s Romelu Lukaku celebrates scoring their second goal against in the French Alps in December Chelsea in their FA cup quarter-final yesterday. 2013 and spent six months in an induced coma before returning to AFP million, 258 million euros) to buy his home in Switzerland to con- Liverpool 49.9 percent of the club, having tinue his rehabilitation. made a pre-match address to sup- Any updates by Kehm on Schu- porters in the media. -

Steven Fletcher Fixar Ny Seger Till Sheffield Wednesday M En Tredjedel Återstår Av Premier League Och Liverpool Har Enorma Spetskvaliteter

8 TIPS LÖRDAG 26 JANUARI 2019 STRYKTIPSETMEDESKILHELLBERG •STRYKTIPSETOCHEUROPATIPSET Steven Fletcher fixar ny seger till Sheffield Wednesday m En tredjedel återstår av Premier League och Liverpool har enorma spetskvaliteter. spelare och comebackande Steven Fletcher och bottenlagen har inte råd att tappa m Jackpot höjer intresset och det borde bli avgjorde mot Charlton. Skyttekungen kan bli många poäng under spurten. Men trots att bra utdelning eftersom flera av matcherna matchhjälte även mot ett sargat Derby. Watford behöver poängen bättre spikas är öppna och svårtippade. ESKIL HELLBERG Spelexpert. Flerfaldig vinnare av de Liverpool. Det skiljer 55 poäng mellan lagen m Sheffield Wednesday har fått tillbaka prestigefyllda ligorna för Stryktips, Europatips och Måltips. PREMIER LEAGUE Senaste mötet: 1–0 THE CHAMPIONSHIP Senaste mötet: 1–1 1.BOURNEMOUTH CHELSEA 8.SHEFFIELDW. DERBY FEM SENASTE: Aston Villa h ..... 2–1 FEM SENASTE: Man. United h .. 0–2 FEM SENASTE: Reading h ......... 0–3 FEM SENASTE: Huddersfield h . 1–1 Brighton h ........ 3–1 Sheffield U b .... 1–2 Hull City b ......... 2–1 Tottenham h ..... 2–1 Barnsley b ........ 1–1 Birmingham b .. 3–3 Swansea City b 3–2 Fulham h ........... 1–1 Arsenal h .......... 1–2 Burnley b .......... 0–3 2 Leicester City b 2–2 B. München h ... 0–3 Luton Town b ... 0–1 Charlton h ......... 1–0 1 Bristol City b .... 2–3 Queens Park b .. 1–2 Rejäl käftsmäll Chelsea förlorade klart mot Bayern och chansen att gå vidare i CL är Steven Fletcher avgjorde. Sheffield Wednesdays skyttekung Steven Fletcher hoppade in och minimal. Ruben Loftus-Cheek och Tammy Abraham var tillgängliga för spel mot Spurs och avgjorde mot Charlton. -

GERMANY - ENGLAND MATCH PRESS KIT Örjans Vall, Halmstad Monday 22 June 2009 - 20.45CET (20.45 Local Time) Group B - Matchday 3

GERMANY - ENGLAND MATCH PRESS KIT Örjans vall, Halmstad Monday 22 June 2009 - 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Group B - Matchday 3 Contents 1 - Match background 6 - Head coach 2 - Team facts 7 - Competition facts 3 - Squad list 8 - Competition information 4 - Group statistics 9 - Tournament schedule 5 - Match officials 10 - Legend Match background Their place in the semi-finals assured, England take on Germany in their closing Group B fixture needing a point to win the section while Horst Hrubecsh's side can guarantee their presence in the last four by avoiding defeat in Halmstad. • England beat Spain 2-0 on Thursday to move on to six points following their 2-1 defeat of Finland. Having been held 0-0 by the Iberians in their opener, Germany's 2-0 success against Finland means they would advance with a defeat at Örjans vall providing Spain fail to beat the Finns and overturn a four-goal differential. • Should Germany and Spain finish level on points, goal difference and goals scored, then coefficient ranking will come into play. Based on points obtained divided by the number of matches played in qualifying for the 2007 and 2009 finals (group stage only), Spain's coefficient is superior, 3.400 to Germany's 2.700. • England have enjoyed the better of the countries' competitive meetings down the years, notably with victories over the Germans in the 1982 UEFA European Championship final and also in the qualifying play-off for the 2007 finals in the Netherlands. • England have four wins and just one defeat from the previous eight encounters. -

Page Number: 1/22 May 22, 2017 at 01:45 PM

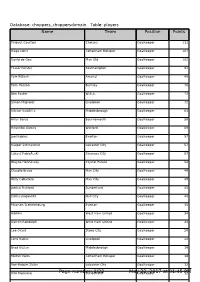

Database: choppers_choppersdomain, Table: players Name Name Team Team PositionPosition PointsPoints Thibaut Courtois Chelsea Goalkeeper 111 Hugo Lloris Tottenham Hotspur Goalkeeper 107 David de Gea Man Utd Goalkeeper 102 Fraser Forster Southampton Goalkeeper 91 Petr ÄŒech Arsenal Goalkeeper 88 Tom Heaton Burnley Goalkeeper 76 Ben Foster W.B.A. Goalkeeper 73 Simon Mignolet Liverpool Goalkeeper 72 VÃctor Valdés Middlesbrough Goalkeeper 63 Artur Boruc Bournemouth Goalkeeper 58 Heurelho Gomes Watford Goalkeeper 58 Joel Robles Everton Goalkeeper 57 Kasper Schmeichel Leicester City Goalkeeper 57 Lukasz FabiaÅ„ski Swansea City Goalkeeper 57 Wayne Hennessey Crystal Palace Goalkeeper 54 Claudio Bravo Man City Goalkeeper 49 Willy Caballero Man City Goalkeeper 49 Jordan Pickford Sunderland Goalkeeper 45 Eldin Jakupović Hull City Goalkeeper 40 Maarten Stekelenburg Everton Goalkeeper 35 Adrián West Ham United Goalkeeper 34 Darren Randolph West Ham United Goalkeeper 34 Lee Grant Stoke City Goalkeeper 28 Loris Karius Liverpool Goalkeeper 24 Brad Guzan Middlesbrough Goalkeeper 19 Michel Vorm Tottenham Hotspur Goalkeeper 16 Ron-Robert Zieler Leicester City Goalkeeper 12 Vito Mannone Page number:Sunderland 1/22 MayGoalkeeper 22, 2017 at 01:45 PM12 Database: choppers_choppersdomain, Table: players Name Name Team Team PositionPosition PointsPoints Jack Butland Stoke City Goalkeeper 11 Sergio Romero Man Utd Goalkeeper 10 Steve Mandanda Crystal Palace Goalkeeper 10 Adam Federici Bournemouth Goalkeeper 4 David Marshall Hull City Goalkeeper 3 Paul Robinson Burnley Goalkeeper 2 Kristoffer Nordfeldt Swansea City Goalkeeper 2 David Ospina Arsenal Goalkeeper 1 Asmir Begovic Chelsea Goalkeeper 1 Wojciech SzczÄ™sny Arsenal Goalkeeper 0 Alex McCarthy Southampton Goalkeeper 0 Allan McGregor Hull City Goalkeeper 0 Danny Ward Liverpool Goalkeeper 0 Joe Hart Man City Goalkeeper 0 Dimitrios Konstantopoulos Middlesbrough Goalkeeper 0 Paulo Gazzaniga Southampton Goalkeeper 0 Jakob Haugaard Stoke City Goalkeeper 0 Boaz Myhill W.B.A. -

3086 Ref Mag 6 V1

FA Learning The Referees’ Association The Football Association 1 Westhill Road 25 Soho Square Coundon London Coventry REFEREEING W1D 4FA CV6 2AD Telephone: Telephone: +44 (0)20 7745 4545 +44 (0)2476 601 701 Joint Publication of The FA and The RA Facsimile: Facsimile: +44 (0)20 7745 4546 +44 (0)2476 601 556 Centenary edition FA Learning Hotline: Email: 0870 8500424 [email protected] Email: Visit: [email protected] www.footballreferee.org Visit: www.TheFA.com/FALearning Why I enjoy refereeing CHRIS FOY Dealing with Mass Confrontation HOWARD WEBB England do have a team at Euro 2008 DAVID ELLERAY From Sheffield to Wembley KEITH HACKETT 3086/08 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTORS 06 David Barber MASS CONFRONTATION Neale Barry Ian Blanchard David Elleray Chris Foy Janie Frampton Keith Hackett Len Randall Dave Raval Steve Swallow Howard Webb Steve & Adam Williams 24 32 FOOTBALL ENGLAND DO FOR ALL HAVE A TEAM AT EURO 2008 POOR QUALITY – NEED EPS VECTOR FILE IF POSS. An exciting summer ahead! David Elleray 04 Dealing with Mass Confrontation – Part 2 Howard Webb 06 Laws of the Game Neale Barry 10 The Rest is History David Barber 12 Preparing for the New Season Steve Swallow 16 Why I enjoy refereeing so much Chris Foy 20 Football for All Dave Raval 24 Father & Son! Steve and Andrew Williams 26 Referee Development Officers Ian Blanchard 30 England do have a team at Euro 2008 David Elleray 32 From Sheffield to Wembley Keith Hackett 34 England’s first Futsal FIFA referee Ian Blanchard 36 FA Recruitment and Retention Task Force David Elleray 37 Wendy Toms – The end of an era! Janie Frampton 38 RA Centenary Conference Len Randall 40 Take your refereeing to the next level! 41 REFEREEING VOLUME 06 3 David Elleray FOREWORD AN EXCITING Summer 2008 looks set to be an The Referees’ Association itself was formed in interesting and exciting one for those in May 1908 and the Centenary is being celebrated England interested in refereeing as well in a variety of ways: Every member who joins as for the referees themselves. -

Manchester United V Wigan Athletic FA Community Shield Sponsored by Mcdonald’S

Manchester United v Wigan Athletic FA Community Shield sponsored by McDonald’s Wembley Stadium Sunday 11 August 2013 Kick-off 2pm FA Community Shield Contents Introduction by David Barber, FA Historian 1 Background 2 Shield results 3-5 Shield appearances 5 Head-to-head 7 Manager profiles 8 Premier League 2012/13 League table 10 Team statistic review 11 Manchester United player stats 12 Wigan player stats 13 Goals breakdown 14 Results 2012-13 15-16 FA Cup 2012/13 Results 17 Officials 18 Referee statistics & Discipline record 19 Rules & Regulations 20-21 Manchester United v Wigan Athletic, Wembley Stadium, Sunday 11 August 2013, Kick-off 2pm FA Community Shield Introduction by David Barber, FA Historian Manchester United, Premier League champions for the 13th time, meet Wigan Athletic, FA Cup-winners for the first time, in the traditional season curtain-raiser at Wembley Stadium. The match will be the 91st time the Shield has been contested. The only match ever to go to a replay was the very first - in 1908. No club has a Shield pedigree like Manchester United. They were its first winners and have now clocked up a record 15 successes. They have shared the Shield an additional four times and have featured in a total of 28 contests. Wigan Athletic, by contrast, were a non-League club until 1978 and are playing the first Shield match in their 81-year history. The FA Charity Shield, its name until 2002, evolved from the Sheriff of London Shield - an annual fixture between the leading professional and amateur clubs of the time. -

22 March 2014 Opposition: Cardiff City Competition

22 March2014 22 Date: 22 March 2014 Western Mail Sunday Times Sun Telegraph Telegraph Opposition: Cardiff City BBC Observer Times Mirror Echo Sun Independent Guardian Mail Competition: League Rodgers sees the power but still demands more Johnson says Liverpool are the people's choice for title Cardiff City Mutch 9, 88, Campbell 25 3 There was a time when the majority of football fans were sick to death of the Liverpool Suarez 16, 60, 90+6, Skrtel 41, 54, Sturridge 75 6 sight of Liverpool parading league titles and dominating the domestic scene but it Referee N Swarbrick Attendance 28,018 is a measure of how much the landscape has changed over the last couple of Total football. Brendan Rodgers did not use the phrase, but as he reviewed the decades that Glen Johnson may well have captured the public mood when he said tactical and technical background to the latest demonstration of Liverpool's brutal Brendan Rodgers' team would be the people's choice to finish top this year. attacking power, the explanation he offered for what had just transpired was While Manchester United and Everton supporters will shake their head at those wholly in keeping with the Dutch philosophy of interchangeable positions and sentiments, within football there is no shortage of admiration for the structural fluidity. way Liverpool are playing right now. It is hard not to warm to a team that gives "There was a great moment whenever Steven Gerrard filled in at right back and the impression there is little point worrying about keeping clean sheets when Glen Johnson played in midfield for a little period," the Liverpool manager said. -

Under-21 Championship

UNDER-21 CHAMPIONSHIP - 2013/15 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Ander Stadium - Olomouc Sunday 21 June 2015 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Sweden Group B - Matchday 2 England Last updated 14/06/2019 12:21CET UEFA UNDER 21 OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Squad list 5 Match officials 7 Competition facts 8 Match-by-match lineups 11 Team facts 15 Legend 17 1 Sweden - England Sunday 21 June 2015 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Ander Stadium, Olomouc Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA European Under-21 Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Cranie 1, Onuoha 27, 3-3 Bjärsmyr 38 (og); 26/06/2009 SF England - Sweden Gothenburg (aet, 5-4pens) Berg 68, 81, Toivonen 75 UEFA European Under-21 Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Cort 29, 79, Cresswell 04/06/1999 QR (GS) England - Sweden 3-0 Huddersfield 44 Carragher 9, Lampard 04/09/1998 QR (GS) Sweden - England 0-2 Sundsvall 87 (P) UEFA European Under-21 Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 05/09/1989 QR (GS) Sweden - England 1-0 Uppsala Eklund 31 White 29; Ingesson 18/10/1988 QR (GS) England - Sweden 1-1 Coventry 67 Final Qualifying Total tournament Home Away Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA Total Sweden 2 1 0 1 2 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 5 1 2 2 5 9 England 2 1 1 0 2 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 5 2 2 1 9 5 2 Sweden - England Sunday 21 June 2015 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Ander Stadium, Olomouc Match background Memories will be stirred of an epic semi-final when Sweden and England meet in the second round of matches in UEFA European Under-21 Championship Group B. -

Manchester United Plc 2012 Annual Report on Form

MERRILL CORPORATION NLUCCA//17-OCT-12 11:01 DISK130:[12ZCV1.12ZCV42501]BA42501A.;31 mrll_1111.fmt Free: 645DM/0D Foot: 0D/ 0D VJ JC1:1Seq: 1 Clr: 0 DISK024:[PAGER.PSTYLES]UNIVERSAL.BST;102 9 C Cs: 3043 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) អ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ፤ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2012 OR អ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR អ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 001-35627 MANCHESTER UNITED PLC (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Cayman Islands (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Sir Matt Busby Way, Old Trafford, Manchester, England, M16 0RA (Address of principal executive offices) Edward Woodward Executive Vice Chairman Sir Matt Busby Way, Old Trafford, Manchester, England, M16 0RA Telephone No. 011 44 (0) 161 868 8000 E-mail: [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A ordinary shares, par value $0.0005 per share New York Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. -

Referee's Newsletter

Capital Football Federation 5 Referee’s Newsletter 2012 | Issue 1 From the Editor Making his international debut! Hello All and welcome back for another season. Things have been busy in the off season for a number of our members and of course for those of us who were lucky enough to be selected for the various National Leagues over the summer months. Some of us have also been busy with the usual pre- season Hilton Petone Tournament and the two different venues that are being used. Ryan Palmer, right Thanks must go to those people This photo was of the officials for a was viewed by the man organising the who have been kind enough to 2nd grade under 13 girls game held referees. He watched the 1st half and supply various photos and stories to in the USA in January 2012. It was gave him some advice on refereeing with make my life easier! And a special a hopeless game that didn’t need a A/Rs, not realising that Ryan had never thanks to Murray Stevenson who has referee. However, they still paid Ryan for done a game at home with A/Rs. This offered his design skills to make this completing his AR duties. chap was more than happy with Ryan’s newsletter look even better. performance and left him to it for the 2nd The next game was in the middle for a half. Anyway, on with the show. 1st grade under 14 boys game – a game Yours in Football. with a lot more “bite”. He considered Both Keith and Ryan were not impressed the standard was somewhat better than with the standard of refereeing over Gibbo NZ.