Venice and the Adriatic the Header

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans ᇺᇺᇺ

when ethnicity did not matter in the balkans when ethnicity did not matter in the balkans ᇺᇺᇺ A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods john v. a. fine, jr. the university of michigan press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2006 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2009 2008 2007 2006 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fine, John V. A. (John Van Antwerp), 1939– When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans : a study of identity in pre-nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the medieval and early-modern periods / John V.A. Fine. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-472-11414-6 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-472-11414-x (cloth : alk. paper) 1. National characteristics, Croatian. 2. Ethnicity—Croatia. 3. Croatia—History—To 1102. 4. Croatia—History—1102–1527. 5. Croatia—History—1527–1918. I. Title. dr1523.5.f56 2005 305.8'0094972–dc22 2005050557 For their love and support for all my endeavors, including this book in your hands, this book is dedicated to my wonderful family: to my wife, Gena, and my two sons, Alexander (Sasha) and Paul. -

Istria & Dalmatia

SPECIAL OFFER - SAVE £200 PER PERSON ISTRIA & DALMATIA A summer voyage discovering the beauty of Istria & Kvarner Bay aboard the Princess Eleganza 28th May to 6th June, 6th to 15th June*, 15th to 24th June, 24th June to 3rd July* 2022 Mali Losinj Brijuni Islands National Park Vineyard in the Momjan region oin us for a nine night exploration of the beautiful Istrian coast combined with a visit to the region’s bucolic interior and some charming islands. Croatia’s Istrian coast and Momjan J Opatija Kvarner Bay offers some of the world’s most beautiful coastal scenery, picturesque islands Porec Motovun Rovinj and a wonderfully tranquil and peaceful atmosphere. The 36-passenger Princess Eleganza CROATIA is the perfect vessel for our journey allowing us to moor centrally in towns and call into Pula secluded bays, enabling us to fully discover all the region has to offer visiting some Brijuni Rab Islands marvellous places which do not cater for the big ships along the way. Each night we will Mali Losinj remain moored in the picturesque harbours affording the opportunity to dine ashore on some evenings and to enjoy the floodlit splendour and lively café society which is so atmospheric. Zadar Our island calls will include Rab with its picturesque Old Town, Losinj Island with its striking bays Dugi Otok which is often to referred to as Croatia’s best-kept secret, Dugi Otok where we visit a traditional fishing village and the islands of the Brijuni which comprise one of Croatia’s National Parks. Whilst in Pula, we will visit one of the best preserved Roman amphitheatres in the world and we will also spend a day travelling into the Istrian interior to explore this area of disarming beauty and visit the village of Motovun, in the middle of truffle territory, where we will sample the local gastronomy and enjoy the best views of the Istrian interior from the ramparts. -

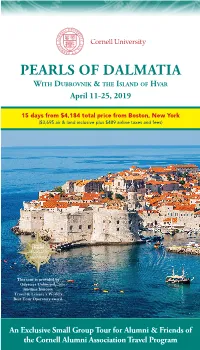

Pearls of Dalmatia with Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar

PEARLS OF DALMATIA WITH DUBROVNIK & THE ISLAND OF HVAR April 11-25, 2019 15 days from $4,184 total price from Boston, New York ($3,695 air & land inclusive plus $489 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumni & Friends of the Cornell Alumni Association Travel Program Dear Alumni, Parents, and Friends, We invite you to be among the thousands of Cornell alumni, parents and friends who view the Cornell Alumni Association (CAA) Travel Program as their first choice for memorable travel adventures. If you’ve traveled with CAA before, you know to expect excellent travel experiences in some of the world’s most interesting places. If our travel offerings are new to you, you’ll want to take a closer look at our upcoming tours. Working closely with some of the world’s most highly-respected travel companies, CAA trips are not only well organized, safe, and a great value, they are filled with remarkable people. This year, as we have for more than forty years, are offering itineraries in the United States and around the globe. Whether you’re ascending a sand dune by camel, strolling the cobbled streets of a ‘medieval town’, hiking a trail on a remote mountain pass, or lounging poolside on one of our luxury cruises, we guarantee ‘an extraordinary journey in great company.’ And that’s the reason so many Cornellians return, year after year, to travel with the Cornell Alumni Association. -

Discovering Dalmatia

PROGRAmme AND BOOK OF AbstRActs DISCOVERING DALMATIA The week of events in research and scholarship Student workshop | Public lecture | Colloquy | International Conference 18th-23rd May 2015 Ethnographic Museum, Severova 1, Split Guide to the DISCOVERING week of events in research and DALMATIA scholarship Student (Un)Mapping Diocletian’s Palace. workshop Research methods in the understanding of the experience and meaning of place Public Painting in Ancona in the 15th century with several lecture parallels with Dalmatian painting Colloquy Zadar: Space, time, architecture. Four new views International DISCOVERING DALMATIA Conference Dalmatia in 18th and 19th century travelogues, pictures and photographs Organized by Institute of Art History – Centre Cvito Fisković Split with the University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy and the Ethnographic Museum in Split 18th-23rd May 2015 Ethnographic Museum, Severova 1, Split (Un)Mapping Diocletian’s Palace. Workshop of students from the University of Split, Faculty Research methods in the of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy - University understanding of the experience study of Architecture and Faculty of Humanities and Social and meaning of place Sciences - Department of Sociology Organisation and Hrvoje Bartulović (Faculty of Civil Engineering, mentoring team Architecture and Geodesy = FGAG), Saša Begović (3LHD, FGAG), Ivo Čović (Politecnico di Milano), Damir Gamulin, di.di., Ivan Jurić (FGAG), Anči Leburić, (Department of Sociology), Iva Raič Stojanović -

The Formation of Croatian National Identity

bellamy [22.5].jkt 21/8/03 4:43 pm Page 1 Europeinchange E K T C The formation of Croatian national identity ✭ This volume assesses the formation of Croatian national identity in the 1990s. It develops a novel framework that calls both primordialist and modernist approaches to nationalism and national identity into question before applying that framework to Croatia. In doing so it not only provides a new way of thinking about how national identity is formed and why it is so important but also closely examines 1990s Croatia in a unique way. An explanation of how Croatian national identity was formed in an abstract way by a historical narrative that traces centuries of yearning for a national state is given. The book goes on to show how the government, opposition parties, dissident intellectuals and diaspora change change groups offered alternative accounts of this narrative in order to The formation legitimise contemporary political programmes based on different visions of national identity. It then looks at how these debates were in manifested in social activities as diverse as football and religion, in of Croatian economics and language. ✭ This volume marks an important contribution to both the way we national identity bellamy study nationalism and national identity and our understanding of post-Yugoslav politics and society. A centuries-old dream ✭ ✭ Alex J. Bellamy is lecturer in Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Queensland alex j. bellamy Europe Europe THE FORMATION OF CROATIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY MUP_Bellamy_00_Prelims 1 9/3/03, 9:16 EUROPE IN CHANGE : T C E K already published Committee governance in the European Union ⁽⁾ Theory and reform in the European Union, 2nd edition . -

The Role of the High Clergy of Croatia, Dalmatia And

Mišo Petrović POPES, PRELATES, PRETENDERS: THE ROLE OF THE HIGH CLERGY OF CROATIA, DALMATIA AND SLAVONIA IN THE FIGHT FOR THE HUNGARIAN THRONE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2015 POPES, PRELATES, PRETENDERS: THE ROLE OF THE HIGH CLERGY OF CROATIA, DALMATIA AND SLAVONIA IN THE FIGHT FOR THE HUNGARIAN THRONE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY by Mišo Petrović (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2015 POPES, PRELATES, PRETENDERS: THE ROLE OF THE HIGH CLERGY OF CROATIA, DALMATIA AND SLAVONIA IN THE FIGHT FOR THE HUNGARIAN THRONE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY by Mišo Petrović (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2015 POPES, PRELATES, PRETENDERS: THE ROLE OF THE HIGH CLERGY OF CROATIA, DALMATIA AND SLAVONIA IN THE FIGHT FOR THE HUNGARIAN THRONE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY by Mišo Petrović (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. -

Illyrianism and the Croatian Quest for Statehood Author(S): Marcus Tanner Source: Daedalus, Vol

Illyrianism and the Croatian Quest for Statehood Author(s): Marcus Tanner Source: Daedalus, Vol. 126, No. 3, A New Europe for the Old? (Summer, 1997), pp. 47-62 Published by: The MIT Press on behalf of American Academy of Arts & Sciences Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027441 Accessed: 19-04-2015 08:03 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press and American Academy of Arts & Sciences are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Daedalus. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Sun, 19 Apr 2015 08:03:08 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Marcus Tanner Illyrianism and the Croatian Quest for Statehood THE FULFILLMENTOF A THOUSAND-YEAR DREAMwas how Franjo Tudjman, leader of Croatia's independence struggle, de scribed his country's recognition by the international com munity in 1992. The phrase was scarcely off his lips that year. It strikes a discordant note in most Western ears?too grandiloquent and vaguely reminiscent of a thousand-year Reich. But it sounded sweet to most Croats, who, like many small, subjugated peoples, are much more obsessed with their own history than those nations that have generally had an easier ride. -

Croatia: a Curriculum Guide for Secondary School Teachers

Croatia: A Curriculum Guide for Secondary School Teachers Created by the Center for Russian and East European Studies University Center for International Studies University of Pittsburgh April 2006 Cover Photo: Jeanette A. Hahn, Dubrovnik, 2004 Curriculum Guide Contributors: Jeanette A. Hahn, School of Law, University of Pittsburgh (primary researcher and author) Gina Peirce, Center for Russian and East European Studies, University of Pittsburgh (editor) ii Introduction Croatia: A Curriculum Guide for Secondary School Teachers was created to provide information on the historical and contemporary development of the Croatian nation, and in so doing, to assist teachers in meeting some of the criteria indicated in the Pennsylvania Department of Education‘s Academic Standard Guidelines (http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/state_board_of_education/8830 /state_academic_standards/529102). To fulfill the fundamental themes for many of the disciplines prescribed by the state guidelines, this curriculum guide provides the following information: A description of the unique traits of Croatian culture. A description of the effects of political, economic and cultural changes and how these changes shaped the present Croatia. Identification and explanation of the contributions of key historical individuals and groups in politics, science, the arts, and religion in Croatia. Examination of the changing economic and political system of Croatia, and how these changes have affected Croatian society. These and other areas of Croatian society and culture are explored in an attempt to assist the secondary school teacher in fulfilling the Academic Standard Guidelines. As the unique transitions in Croatia provide a laboratory for studying political, economic and cultural change, this guide may be additionally useful as a means for comparison with our own country‘s development. -

CO-364 FRENCH TOPOGRAPHIC and HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEYS of DALMATIA in the NAPOLEONIC PERIOD ALTIC M. Institute of Social Sciences

CO-364 FRENCH TOPOGRAPHIC AND HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEYS OF DALMATIA IN THE NAPOLEONIC PERIOD ALTIC M. Institute of Social Sciences, ZAGREB, CROATIA The Treaty of Pressburg signed between Austria and France in December 1805 incorporated the entire Croatian coast into Napoleon's French Empire. Though only seven years under the French rule, Croatia owes France a debt of gratitude for the first systematic topographic survey of Dalmatia, conducted between 1806 and 1811, as well as for the first hydrographic survey of the Adriatic, conducted between 1806 and 1809. This paper analyzes all the above stated maps and charts that were created during the French topographic and hydrographic surveys of the Croatian coast, presenting the results of new research and displaying some of the hitherto unpublished maps and charts from the period of the French administration of Dalmatia. At the same time, the paper assesses the overall contribution of French cartography to the mapping of the Croatian Adriatic coast, discussing the impact of the above stated surveys on the French- Croatian cultural and scientific connections during the Napoleonic period. I – THE FIRST HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEY OF THE EASTERN ADRIATIC COAST (1806-1809) The interest of the French in mapping the Croatian littoral was due to the geostrategic position of Dalmatia in the Napoleonic Wars. From 1806, when the French gained control of Dalmatia, through 1813, when the entire Dalmatian coast was re-incorporated into Austria, the Croatian side of the Adriatic was playing an important role in the war between France, Russia and England. Because of numerous naval operations of the French against the English in the Adriatic, as early as 1806, Napoleon ordered a hydrographic reconnaissance of the entire Croatian Adriatic coast. -

"Zagora" and Its Reference to Areas in the Dalmatian Hinterland in The

GEOGRAPHIC NAME ZAGORA AND ITS REFERENCE TO AREAS IN THE DALMATIAN HINTERLAND IN THE SELECTED NEWSPAPER MEDIUM GEOGRAFSKO IME ZAGORA I NJEGOVA POJAVNOST NA PODRUČJIMA DALMATINSKOGA ZALEĐA U ODABRANOM NOVINSKOM MEDIJU BRANIMIR VUKOSAV1 1Odjel za geografiju, Sveučilište u Zadru / Department of Geography, University of Zadar UDK: 911.5:811.163.42’373.21:050](497.5)=1 Primljeno / Received: 2011-10-17 Izvorni znanstveni članak Original scientific paper In the Croatian language, the word "zagora" or "zagorje" refers to an area "on the other side of a mountain or a hill". Throughout history, this term has been widely used to describe places physically detached from some other, economically or politically more prominent areas; and has thus been adopted as a geographic name (toponym) for places which were "in contrast" to such areas and separated from them by an element of terrain. The term zagora is therefore a geographic name which denotes an area observed from an outside point of view, and which is later on accepted by the domicile population, becoming an endonym. In the context of the Croatian national territory, the most prominent usage of this toponym has been present in specific traditional regions in northern and southern Croatia; namely, Hrvatsko zagorje in northern Croatia, and a rather undefined area in the Dalmatian hinterland in southern Croatia. The extent and the degree of identification of the areas in southern Croatia bearing that particular geographic name have not been precisely defined, although there are many obvious indications of the existence of such a region in many contemporary sources. The aim of this paper is to research the perceptual character of an area in the Dalmatian hinterland in relation to geographic names Zagora and Dalmatinska zagora by means of content analysis. -

The Influence of Lime Production on the Landscape of the Northern Dalmatian Islands

geosciences Article Human Footprints in the Karst Landscape: The Influence of Lime Production on the Landscape of the Northern Dalmatian Islands (Croatia) Josip Fariˇci´c 1,* and Kristijan Juran 2 1 Department of Geography, University of Zadar, 23000 Zadar, Croatia 2 Department of History, University of Zadar, 23000 Zadar, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Throughout history, the production of lime on the Croatian islands, which are mostly made of limestone and dolomite, has been an important economic activity. In the northern Dalmatian islands, which are centrally positioned on the northeastern Adriatic coast, lime was produced for local needs, but also for the purposes of construction in the nearby cities of Zadar and Šibenik. On the basis of research into various written and cartographic archival sources relating to spatial data, in addition to the results of field research, various traces of lime production have been found in the landscape of the northern Dalmatian islands. Indications of this activity in the insular karst are visible in anthropogenic forms of insular relief (lime kilns, small quarries, stone deposits) and in degraded forms of Mediterranean vegetation. This activity has also left its mark on the linguistic landscape in the form of toponyms, indicating that lime kilns were an important part of the cultural landscape. Keywords: lime kiln; karst; insular landscape; environmental changes; northern Dalmatia; Croatia Citation: Fariˇci´c,J.; Juran, K. Human Footprints in the Karst Landscape: The Influence of Lime Production on the Landscape of the Northern 1. Introduction Dalmatian Islands (Croatia). The object of the research that preceded this article is the impact of lime production on Geosciences 2021, 11, 303. -

PEARLS of DALMATIA with Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar May 21-June 4, 2015

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts presents PEARLS OF DALMATIA With Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar May 21-June 4, 2015 15 days for $5,484 total price from Washington, DC ($4,795 air & land inclusive plus $689 airline taxes and departure fees) An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Members of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts PEARLS OF DALMATIA With Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar 15 days for $5,484 total price from Washington, DC ($4,795 air & land inclusive plus $689 airline taxes and departure fees) ndependent, democratic Croatia welcomes visitors eager to absorb its remarkable I history and culture – and its beautiful and unspoiled Dalmatian coastline. As our small group travels from historic Zagreb and beautiful Lake Bled to the Habsburg resort of Opatija, the island of Hvar, and beloved Dubrovnik, we see why this cherished region lays such a claim on the hearts of all who visit. Day 1: Depart U.S. for Zagreb, Croatia SLOVENIA Ljubljana Zagreb Day 2: Arrive Zagreb After a connecting flight CROATIA in Europe, we arrive in Zagreb and transfer to our Opatija hotel. Tonight we meet our fellow travelers and learn about the journey ahead as we gather for a briefing and welcome dinner. D Adriatic Sea Trogir Day 3: Zagreb This morning’s tour of the Croatian capital by coach and on foot reveals a gra- Destination Hvar Motorcoach Dubrovnik cious city of culture and hospitality. We visit Mirogoj Ferry Park Cemetery, known for its arcades and sculpture; Entry/Departure then continue through Old Town with a visit to St.