Stitchery5 – Applique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

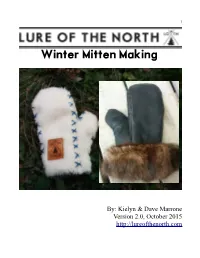

Winter Mitten Making

1 Winter Mitten Making By: Kielyn & Dave Marrone Version 2.0, October 2015 http://lureofthenorth.com 2 Note 1- This booklet is part of a series of DIY booklets published by Lure of the North. For all other publications in this series, please see our website at lureofthenorth.com. Published instructional booklets can be found under "Info Hub" in the main navigation menu. Note 2 – Lure Mitten Making Kits: These instructions are intended to be accompanied by our Mitten Making Kit, which is available through the “Store” section of our website at: http://lureofthenorth.com/shop. Of course, you can also gather all materials yourself and simply use these instructions as a guide, modifying to suit your requirements. Note 3 - Distribution: Feel free to distribute these instructions to anyone you please, with the requirement that this package be distributed in its entirety with no modifications whatsoever. These instructions are also not to be used for any commercial purpose. Thank you! Note 4 – Feedback and Further Help: Feedback is welcomed to improve clarity in future editions. For even more assistance you might consider taking a mitten making workshop with us. These workshops are run throughout Ontario, and include hands-on instructions and all materials. Go to lureofthenorth.com/calendar for an up to date schedule. Our Philosophy: This booklet describes our understanding of a traditional craft – these skills and this knowledge has traditionally been handed down from person to person and now we are attempting to do the same. We are happy to have the opportunity to share this knowledge with you, however, if you use these instructions and find them helpful, please give credit where it is due. -

Jan's Bonus Embellishment Tips

Jan's Bonus Embellishment Tips BONUS! Add a sliver of color to your quilting! This technique is simple and effective for adding a touch of color and style to any quilt project. You'll see this technique on many of Jan's quilts. We are going to make a sample that you'll keep in your notebook for reference. Adding a sliver of color – Determine the width for the accent color. For our sample, we will make a 1/4" sliver of color between two strips of fabric. You can see this effect by examining Jan's Spiral Lone Star quilt (look at the outer diamond units nearest the binding). a – Two fabrics, joined by a single seam. b – Determine the desired width of the accent strip. Add 1/4" seam allowance. Multiply X 2 for accent strip width. c – The same two fabrics plus a contrasting accent strip, attached to the left fabric. For your samples – Cut: 1 – 2" strip of fabric, selvage to selvage. sub-cut into into two pieces. Cut : 1 – 1" x 12" strip of accent color – choose cotton or lamé fabric. Follow the steps below. Attach the samples to the pages and keep in your notebook. 1 – Two 2" strips of fabric one 1" strip of accent color (white strip in illustrations) 2 – Set the sewing machine to stitch at 1/2" by positioning a ruler beneath the presser foot. Lower the needle to touch the 1/2" 2 – Option: add blue tape to follow mark. Lower the presser foot to hold the ruler in place. -

23. Embroidery As an Embellishment in Fabric Decoration

EMBROIDERY AS AN EMBELLISHMENT IN FABRIC DECORATION By OLOWOOKERE PETER OLADIPO Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Federal College of Education, Osiele, Abeokuta. Abstract Nigeria is endowed with abundant human, natural and material resources, which could be used in different vocational practices. Practitioners have consistently practiced their art with attention to uniqueness and high quality forms, styles and content. Embroidery as a decorative process in Art has played principal roles in entrepreneurship development. Hence, this paper made a critical analysis of the forms, content and significant of embroidery in art, the thread colours, fabric motifs and pattern suitable for a successful embroidery design would also be considered. The general conclusion is that if embroidery is properly done, it would increase the embroiderers sense of creativity in our societal growth and the interested individual should be encourage to learn the craft so that the tradition will remain forever. Embroidery is an interesting stitching technique by which coloured threads, generally of silk or wool are used with a special needle to make a variety of stitches, and it is used to make an attractive design on garment, wall hanging or upholstery pieces. In Nigeria today, embroidery clothing are used far and wide and its unique feature and elegance remain the ability to trill and appeal to the people’s fervent love for it whereby the artisan considered different textile materials such as guinea brocade, damask and bringing out the significance of thread with which it is worked. Ojo (2000) defined, embroidery as an art of making pattern on textiles, leather, using threads of wool, linen, silk and needle. -

Expression2038 - 2048

expression2038 - 2048 Owner’s manual This household sewing machine is designed to comply with IEC/EN 60335-2-28 and UL1594 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS When using an electrical appliance, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: Read all instructions before using this household sewing machine. DANGER - To reduce the risk of electric shock: • A sewing machine should never be left unattended when plugged in. Always unplug this sewing machine from the electric outlet immediately after using and before cleaning. • Always unplug before relamping. Replace bulb with same type rated 5 Watt. WARNING - To reduce the risk of burns, fi re, electric shock, or injury to persons: • Do not allow to be used as a toy. Close attention is necessary when this sewing machine is used by or near children or infi rm person. • Use this sewing machine only for its intended use as described in this manual. Use only attachments recommended by the manufacturer as contained in this manual. • Never operate this sewing machine if it has a damaged cord or plug, if it is not working properly, if it has been dropped or damaged, or dropped into water. Return the sewing machine to the nearest authorised dealer or service center for examination, repair, electrical or mechanical adjustment. • Never operate the sewing machine with any air openings blocked. Keep ventilation openings of the Sewing machine and foot controller free from the accumulation of lint, dust, and loose cloth. • Keep fi ngers away from all moving parts. Special care is required around the Sewing machine needle. • Always use the proper needle plate. -

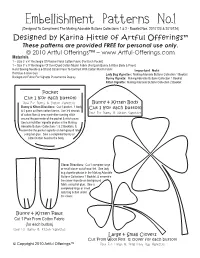

Embellishment Patterns No.1 (Designed to Compliment the Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 & 2 - Booklet Nos

Embellishment Patterns No.1 (Designed To Compliment The Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 & 2 - Booklet Nos. 2010123 & 2010124) Designed by Karina Hittle of Artful Offerings™ These patterns are provided FREE for personal use only. © 2010 Artful Offerings™ ~ www.Artful-Offerings.com Materials 1 ~ Size 3” x 4” Rectangle Of Plaid or Floral Cotton Fabric {For Each Pocket} 1 ~ Size 3” x 5” Rectangles Of Over-Dyed Cotton Muslin Fabric {For Each Bunny & Kitten Body & Paws} Hand Sewing Needle & 6-Strand Cotton Floss To Contrast With Cotton Muslin Fabric Important Note Hot Glue & Glue Gun Lady Bug Vignettes: Making Adorable Buttons Collection 1 Booklet Background Fabric For Vignette Placement & Display Bunny Vignette: Making Adorable Buttons Collection 1 Booklet Kitten Vignette: Making Adorable Buttons Collection 2 Booklet Pocket Cut 1 (for each button) Used For Bunny & Kitten Vignettes Bunny & Kitten Body Bunny & Kitten Directions: Cut 1 pocket , 1 body Cut 1 (for each button) & 2 paws out from cotton fabrics. Use 3-6 strands Used For Bunny & Kitten Vignettes of cotton floss & sew a primitive running stitch around the perimeter of the pocket & stitch paws. See bunny/kitten vignette photos in the Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 & 2 Booklets, & assemble the pocket vignette on background fabric using hot glue. Sew a completed bunny or kitten button head to the body. Clover Directions: Cut 1 complete large or small clover out of wool felt. See lady bug vignette photos in the Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 Booklet, & assemble the clover vignette on background fabric using hot glue. Sew a completed large or small lady bug button under the clover. -

Bobbinwork Basics by Jill Danklefsen

SPECIAL CLASSROOM EDITION BOBBINWORK BASICS BY JILL DANKLEFSEN obbinwork is a technique that places heavy decorative 4. The type of stitch chosen as well as the type of “bobbin yarn” Bthreads on the surface of the fabric, sewn as machine-fed selected will dictate how loose the tension needs to be adjusted decorative stitches or as freemotion stitches. Typically, these on the bobbin case. threads, yarns, and cords are too large to fit through the eye of the sewing machine needle. So, in order to achieve a “stitched 5. Remember the rule of tension adjustment --“Righty, Tighty -- look”, you sew with the heavy decorative thread wound onto a Lefty, Loosey” bobbin and placed in the bobbin case of the machine. 6. Use a “construction quality” thread on the “topside” of your machine, as the needle tension will usually be increased. Think of the top thread as literally pulling the “bobbin yarn” into place to form the stitch pattern. 7. Bobbins can be wound by hand or by machine. Whenever possible, wind the bobbin using the bobbin winder mechanism on the machine. This will properly tension the “bobbin yarn” for a better stitch quality. 8. Bobbinwork can be sewn with the Feed dogs up or down. If stitching freemotion, a layer of additional stabilizer or the use of a machine embroidery hoop may be necessary. 9. Select the proper presser foot for the particular bobbinwork YARNS AND THREADS SUITABLE FOR BOBBINWORK technique being sewn. When working with the heavier “bobbin yarns”, the stitches produced will be thicker. Consider selecting • Yarns (thinner types, often a foot with a large indentation underneath it, such as Foot used for knitting machines) #20/#20C.This foot will ride over the stitching much better. -

MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES 7640 INTRODUCTION Welcome

INSTRUCTION MANUAL MANUEL D’INSTRUCTION MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES 7640 INTRODUCTION Welcome Welcome to the SINGER® family and CONGRATULATIONS on purchasing a brand new SINGER® sewing machine! The SINGER® brand has stood for quality in sewing for over 160 years. We design our machines for sewists of all skill levels so that the joy of sewing, creating, do-it-yourself, crafting and more can be enjoyed by all. It is important to us that you have the easiest and most successful sewing experience. We have provided an instruction manual with easy-to-understand graphics and step-by-step instructions. Additional assistance, by region, may be found on the web at www.singer.com. We’re ready to help and hope that you enjoy your SINGER® sewing machine. Happy Sewing! 2 INTRODUCTION Important Safety Instructions This household sewing machine is designed to comply with IEC/EN 60335-2-28 and UL1594. IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS When using an electrical appliance, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: Read all instructions before using this household sewing machine. Keep the instructions in a suitable place close to the machine. Make sure to hand them over if the machine is given to a third party. DANGER - To reduce the risk of electric shock : - A sewing machine should never be left unattended when plugged in. Always unplug this sewing machine from the electric outlet immediately after using and before cleaning, removing covers, lubricating or when making any other user servicing adjustments mentioned in the instruction manual. WARNING - To reduce the risk of burns, fire, electric shock, or injury to person : - Do not allow to be used as a toy. -

Stitches and Seam Techniques

Stitches and Seam Techniques Seen on Dark Age / Medieval Garments in Various Museum Collections The following notes have been gathered while attempting to learn stitches and construction techniques in use during the Dark Ages / Medieval period. The following is in no way a complete report, but only an indication of some techniques observed on extant Dark Ages / Medieval garments. Hopefully, others who are researching “actual” garments of the period in question will also report on their findings, so that comparisons can be made and a better total understanding achieved. Jennifer Baker –New Varangian Guard – Hodegon Branch – 2009 Contents VIKING AND SAXON STITCHES 1. RUNNING STITCH 2. OVERSEWING 3. HERRINGBONE 4. BLANKET STITCH SEAMS 1. SEAMS 2. BUTTED SEAMS 3. STAND-UP SEAM 4. SEAMS SPREAD OPEN AFTER JOIN IS MADE 5. “LAPPED” FELL SEAM 6. FELL SEAM WORKED ON WRONG SIDE OF GARMENT FINISHES ON RAW EDGES OF SEAMS SEWING ON TABLET WOVEN BRAID HEMS OTHER STITCHES FOUND IN ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDS REFERENCES 1 Stitches and Seam Techniques VIKING AND SAXON STITCHES There are only four basic stitches to master: 1. RUNNING STITCH , 2. OVERSEWING, ALSO KNOWN AS OVERCAST STITCH OR WHIP STITCH 3. HERRINGBONE , ALSO KNOWN AS CATCH STITCH 4. AND BLANKET STITCH. ALSO KNOWN AS BUTTONHOLE STITCH Running stitch is probably the easiest to start with followed by oversewing. With these two stitches you can make clothing. The other two are for decorative edging. These directions are for a right handed person, if you are left handed remember to reverse all directions. 2 Stitches and Seam Techniques RUNNING STITCH A running stitch is done through one or more layers of fabric (but normally two or more), with the needle going down and up, down and up, in an essentially straight line. -

Design Iterations Through Fusion of Additive and Subtractive Design

DESIGN ITERATIONS THROUGH FUSION OF ADDITIVE AND SUBTRACTIVE DESIGN A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Gordon Stumpo May 2016 i Thesis written by Gordon Stumpo B.A., Washington State University, 2014 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Vince Quevedo, Thesis Supervisor Brian Peters, Committee Member Margarita Benitez, Committee Member Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ……………………………………………………………………………………….……….…….….vi LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………………...……….………..xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………………………………...………..………..xii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………..………….13 Concept……………………………………………………………………………………...................................13 Design Framework…………………………………………………………………………………………..…13 Surface and Structure Frameworks…………………………………………………………….….……14 Additive Design…………………………………………………………………………………………..…..….18 Subtractive Design……………………………………………………….……………………………....….…18 Tension…………….……………………………………………………………………………….…………..…..18 Price Point…………….…………………………….………………………………………………………...…..19 Personal Skills & Background…………….……………………………………………………….…..…..19 Problem Statement & -

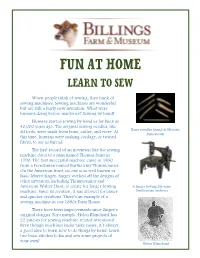

Learn to Sew!

Fun at Home Learn to Sew When people think of sewing, they think of sewing machines. Sewing machines are wonderful but are still a fairly new invention. What were humans doing before machines? Sewing by hand! Humans started sewing by hand as far back as 40,000 years ago. The original sewing needles, like all tools, were made from bone, antler, and ivory. At Bone needles found at Historic Jamestown this time, humans were making cordage, or twined fibers, to use as thread. The first record of an invention like the sewing machine dates to a man named Thomas Saint in 1790. The first successful machine came in 1830 from a Frenchman named Barthelemy Thimmonnier. On the American front, no one is as well known as Isaac Merrit Singer. Singer worked off the designs of other inventors, including Thimmonnier and American Walter Hunt, to create his Singer Sewing A Singer Sewing Machine, machine. Since its creation, it has allowed for easier Smithsonian Archives and quicker creations. There’s an example of a sewing machine in our 1890s Farm House. There have been improvements since Singer’s original designs. For example, Helen Blanchard has 22 patents for sewing machine related inventions! Even though machines make tasks easier, it’s always a good idea to learn how to do things by hand. Learn two basic stitches to fix and sew some projects of your own! Helen Blanchard Craft: Stitches Here is an outline for two basic stitches. All you need is a needle, thread, and some scrap pieces of fabric. Once you get the hang of these, search for more to master! The Running Stitch 1. -

THE SLOW HANDS LAB the Slow Hands’ Lab

THE SLOW HANDS LAB The Slow Hands’ Lab A Thesis Project by Jiayi Dong Class of 2019 MFA, Design for Social Innovation School of Visual Arts Thesis Advisor Archie Lee Coates IV TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 3 DESIGN PROCESS 9 INTERVENTION 31 LEARNINGS 45 LOOKING FORWARD 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 49 INTRODUCTION Suzhou embroidery (Su embroidery for short) was originated in Suzhou, China and later on spread to the neighboring areas such as Nantong and Wuxi in Jiangsu province. These areas, locat- THE HISTORY ed in the lower reach of Youngest River, have been famous for their high quality silk produc- OF SU EMBROIDERY ART tions for centuries. The fertile soil, mild tempera- ture, and booming production of silk fabric and thread naturally nourished the burgeoning and flourishing of Suzhou embroidery. According to "Shuo Yuan", written by Liu Xiang during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 24 AD), the country of Wu (current Suzhou area) has started to use embroidery to decorate garments over 2,000 years ago. As described in the book of "Secret Treasures of Qing," the Suzhou embroi- ders in Song Dynasty (960-1279) used "needles that could be as thin as the hair. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Suzhou has become a thriving center for silk industries and handicrafts. Artists in Wu area, represented by Tang Yin (Bohu) and Shen Zhou, helped the further development of Suzhou embroidery. Embroiders reproduced their paintings using needles. These works were so vivid and elegant as to be called "paintings by needle" or "unmatch- able even by the nature." Since then, Suzhou embroidery evolved a style of its own in needle- work, color plan and pattern. -

COLORFUL TRIANGLE THROW | Crochetpage 1 of 2 AAAAA BBBBBB

Throw measures 32 x 50” (81 x 127 cm) EDGING With right side facing, join E with a slip st SPECIAL STITCH anywhere along edge of Throw. sc2tog = [draw up a loop in next st] twice, Round 1: Ch 1, sc in same st as yarn join, yarn over and draw through all 3 loops on sc in each sc around, working 2 sc in each hook. corner, join with slip st in first sc. Round 2: Ch 1 sc in each sc around, working CROCHET TRIANGLE MOTIFS 3 sc in each corner, join with slip st in first sc. SKILL LEVEL Make 20 with each A and C, and 24 with Round 3: Ch 1, sc in each sc around, join EASY each B and D. with slip st in first sc. Ch 16. Round 4: Ch 1, reverse sc around, join with Designed by Marianne Forrestal Row 1 (wrong side): Sc in 2nd ch from slip st in first sc. hook and each ch to end, turn – 15 sc. Fasten off. Rows 2 and 3 (decrease rows): Ch 1, sc2tog What you will need: over first 2 sts, sc in each st to end, turn. – FINISHING 13 sc. Weave in ends. RED HEART® Soft®: 2 balls each Row 4: Ch 1, sc in each st to end, turn. 9251 Coral A; 9010 Charcoal B, 4420 Guacamole C, and 9520 Rows 5-8 (decrease rows): Repeat Row ABBREVIATIONS Seafoam D; 3 balls 4601 Off 2 – 9 sc. ch = chain; sc = single crochet; st(s) = White E Repeat the last 5 rows twice more – 1 st.