AILA Issue Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Documentary Photography

RETHINKING DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY: DOCUMENTARY AND POLITICS IN TIMES OF RIOTS AND UPRISINGS —————————————————— A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University —————————————————— In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Art History —————————————————— by Jack Opal May 2013 Introduction I would like to think about documentary photography. In particular, I would like to rethink the limits of documentary photography for the contemporary. Documentary, traditionally, concerns itself with the (re)presentation of factual information, constitutes a record.1 For decades, documentary – and especially social documentary – has been under siege; its ability to capture and convey and adequately represent “truth” thrown into question, victim to the aestheticization of the objects, fading trust in their authors, and technological development. So much so that the past three decades have prompted photographer, documentarian, and art historian Martha Rosler to question first its utility, then its role, and finally its future in society. All of this has opened up the possibility and perhaps the need to reconsider the conditions and purpose of documentary practice, and to consider the ways in which it has been impacted by recent technological and historical developments. The invention of the internet and the refinement of the (video) camera into ever more portable devices and finally into the smartphone, and the rise to ubiquity within society of these inventions, signifies a major shift in documentary. So, too, have certain events of the past two decades – namely, the beating of Rodney King (and the circulation of the video of that event) and the development and adoption of the occupation as a major tactic within the political left. -

Human Rights Zone: Building an Antiracist City in Tucson, Arizona

Human Rights Zone: Building an antiracist city in Tucson, Arizona Jenna M. Loyd 1 [email protected] Abstract: Tucson, Arizona is on the front lines of border militarization and the criminalization of migration. Residents there are crafting creative responses to the state and federal government’s increasingly punitive treatment of migration. This critical intervention piece focuses on the We Reject Racism campaign as an effort to build an antiracist city in conditions of steady police and military presence. It situates this campaign in a historical lineage of building open and sanctuary cities, and suggests that demilitarization and decriminalization should be recognized as central aspects of antiracist Right to the City organizing. I arrived in Tucson, Arizona on the afternoon of July 28, 2010. Immediately, I spotted signs that read “We Reject Racism: Human Rights Respected Here” dotting modest front yards and lining storefronts of businesses near downtown. Soon these same signs, and many others, would fill the city’s streets. The immediate issue was Senate Bill 1070, a state law that would require police officers engaged in a legal stop to question people about their migration status and to arrest them if they could not produce paperwork verifying the legality of their presence. The bill received national and international criticism for enshrining a ‘Papers, please’ policy, and promising a future of racial profiling and civil rights abuses. The stated goal of SB 1070 is “attrition through enforcement,” and includes provisions for policing daily mobility and work that would make everyday life for undocumented migrants so difficult, legally and economically, that they would 1 Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Building an antiracist city in Tucson, Arizona 134 have no choice but to leave the state (or ‘self-deport’). -

Copwatching Jocelyn Simonson Brooklyn Law School, [email protected]

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 4-2016 Copwatching Jocelyn Simonson Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation 104 Cal. L. Rev. 391 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. Copwatching Jocelyn Simonson* This Article explores the phenomenon of organized copwatching-groups of local residents who wear uniforms, carry visible recording devices, patrol neighborhoods, and film police- citizen interactions in an effort to hold police departments accountable to the populations they police. The Article argues that the practice of copwatching illustrates both the promise of adversarialism as a form of civic engagement and the potential of traditionally powerless populations to contribute to constitutional norms governing police conduct. Organized copwatching serves a unique function in the world of police accountability by giving these populations a vehicle through which to have direct, real-time input into policing decisions that affect their neighborhoods. Many scholars recognize that a lack ofpublic participationis a barrier to true police accountability. When searchingfor solutions these same scholars often focus on studying and perfecting consensus-based methods of participation such as community policing, and neglect the study of more adversarial, confrontational forms of localparticipation in policing. By analyzing copwatching as a form of public participation,this Article challenges the scholarly focus on consensus-based strategies of police accountability. The Article urges scholars and reformers to take adversarial,bottom-up mechanisms of police accountability seriously-not just as protest, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38SK27 Copyright © 2016 California Law Review, Inc. -

Ppr47i Final?

issue #47 may www. portlandcopwatch. org 2009 Auditor Blackmer to resign May 18 —see p. 2 Chief Sizer Finally Releases (Good Secret List Allowed to Continue, Beginning of) Racial Profiling Plan With Reservations, In Judge’s Ruling ...on the Same Day the Police Review Board he controversial plan which Portland Mercury, January 15 Publishes Its “Bias Based Policing” Report forces repeat arrestees to enter SUCCESSOR TO RACIAL PROFILING COMMITTEE IGNORES Ttreatment or face felony charges for EXPLICIT POLICE BIGOTRY IN GANG CRACKDOWN misdemeanor crimes—Project 57/ oughly two years after the deadline given her by aka the Neighborhood Livability community groups, Portland Police Chief Rosie Sizer Enforcement Program (NLECP)— Rreleased her plan to reduce racial profiling on Feb. 18. went on trial in early 2009. The That morning, the Citizen Review Committee (CRC) program depends on a secret list of published its own interim report on “Disparate Treatment some 400 people who are targeted Complaints” examined as chronic offenders (PPR #46). On by its Bias Based Policing April 8, Multnomah Circuit Court Work Group. At the Judge Dale Koch ruled that the City March 18 meeting of the could not use the list to stiffen people’s charges. However, he “Community/Police also said they could present suspects’ repeat convictions (not just Relations Committee” of arrests) to the District Attorney on a case by case basis for review. the new Human Rights As a result, two of five defendants in the case will be charged This image found on the KALB-TV Commission (HRC), with felonies based on their previous records. -

Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest

Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest Exhibit Catalog Reformatted for use on the Chicano/Latino Archive Web site at The Evergreen State College www.evergreen.edu/library/ chicanolatino 2 | Chicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest A touring exhibition and catalog, with interpretive historical and cultural materials, featuring recent work of nine contemporary artists and essays by five humanist scholars. This project was produced at The Evergreen State College with primary funding support from the Washington Commission for the Humanities and the Washington State Arts Commission Preliminary research for this arts and humanities project was carried out in 1982 with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Exhibiting Artists Cecilia Alvarez Alfredo Arreguín Arturo Artorez Paul Berger Eduardo Calderón José E. Orantes José Reynoso José Luís Rodríguez Rubén Trejo Contributing Authors Lauro Flores Erasmo Gamboa Pat Matheny-White Sid White Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Contents ©1984 | 3 Introduction and Acknowledgements TheChicano and Latino Artists in the Pacific Northwest During the first phase of this project, funded by the project is the first effort to develop a major touring National Endowment for the Humanities in 1982, primary exhibition presenting works by Pacific Northwest Chicano field research was completed to identify artists’ public and and Latino artists. This project also features a catalog and personal work, and to gather information on social, cultural other interpretive materials which describe the society and and demographic patterns in Washington, Oregon and culture of Chicano/Latino people who have lived in this Idaho. Materials developed in the NEH project included region for generations, and the popular and public art that a demographic study by Gamboa, an unpublished social has expressed the heritage, struggles and aspirations of this history of artists by Ybarra-Frausto, and a survey of public community. -

Movimiento Art Chicano Public Art in the 1970’S

Movimiento Art Chicano Public Art in the 1970’s Frank Hinojsa. Chicanismo, mural executed with student assistants, acrylic, auditorium, Northwest Rural Opportunities, Pasco, WA., 1975, 8 x 15 ft. Photographed by Bob Haft. A visual dictionary of Chicano art, this mural presents a survey of Movimiento iconography through the inclusion of Chicano racial, political and cultural symbols. Produced with local high school students assisting the artist, it is an important public work rich in cultural content. The largest proportion of Chicano murals in the Northwest are located in social services agencies which include Northwest Rural Opportunities, El Centro de la Raza and educational institutions. Major mural and poster production centers were El Centro de la Raza, and the University of Washington, in Seattle, and Colegio César Chávez, Mt. Angel, Oregon. All Chicano murals in the Pacific Northwest except three are indoors. The art of the Movimiento has yet to Pedro Rodríguez, El Saber Es La Libertad, (detail), become a recognized and visible part of mural, lobby, Northwest Rural Opportunities, Granger, Wa., 1976, 8 x 11 ft. Commissioned by the Pacific Northwest art history. Addressed to Washington State Arts Commission and the Office the needs of a struggling minority communi- of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction. ty, rather than to the mainstream art world, Photographed by Bob Haft. Northwest Chicano art was shaped by goals and approaches that transcended regional Rodríquez’s mural presents a symbol that appears boundaries. Ideas and stimulation came, frequently in movimiento art: the three-faced directly or indirectly, from many sources: mestizo image symbolizes the fusion of the Spaniard pre-Columbian art; vernacular art forms; and the Indian into the central figure of the Chicano. -

Keeping Citizenship Rights White: Arizona's Racial Profiling Practices in Immigration Law Enforcement

K E EPIN G C I T I Z E NSH IP RI G H TS W H I T E : A RI Z O N A’S R A C I A L PR O F I L IN G PR A C T I C ES IN I M M I G R A T I O N L A W E N F O R C E M E N T Mary Romero1 IN T R O DU C T I O N This article analyzes policing practices that result in the mistreatment of citizens and immigrants of color in Arizona and argues that discriminatory and discretionary policing, by both formal and informal means, connects citizenship rights to race. The article begins with an overview of racial profiling and by reviewing the conceptual frameworks primarily applied to the Black experience in the U.S. and demonstrate the usefulness of those frameworks in analyzing the experience of Latinos in the U.S. Next, the article identifies law enforcement racial profiling practices and examines the relationship between those practices and other discretionary powers used by law enforcement to deny Latinos the same treatment as white citizens or white immigrants. Then, drawing on newspaper accounts, law enforcement reports, human and civil rights reports, and lawsuits filed against Maricopa County, the article discusses the risk that citizens and immigrants of color face as a result of racial profiling in immigration law enforcement. This section focuses on narratives from Melendres v. Arpaio and a similar care involving Velia Meraz and her brother Manuel Nieto. -

Annual Report 2019

EL CENTRO de la RAZA | 2019 ANNUAL REPORT BUILDING THE BELOVED COMMUNITY NOW ON THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES SUCCESS STORIES building unity CONTENTS LETTER from the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND BOARD PRESIDENT PARENTCHILD+ PROGRAM Success Stories Emily Estimad@s Amig@s, ParentChild+ Program 1 2019 marked the end of an amazing decade, thanks to you. Whether you are a long-time Emily used to be quiet and timid, but her Letter from the Executive Director supporter or had recently heard of us, you inspire the “Beloved Community” with your self-confidence skyrocketed after her and Board President 2 commitment, generosity, and selflessness. When we reflect on the past year, we recognize that enrollment at José Martí Child Development you have helped improve our communities in significant ways by: Our Services | Our Outcomes 3 Center. JMCDC teachers helped Emily make • Earning a place in North American history after our main building was announced on the this transition by establishing a routine, National Register of Historic Places because El Centro de la Raza is rife with cultural, social, Our Mission 4 befriending her classmates, and reading and political significance. books about feelings and emotions. By the Success Stories • Expanding our culturally responsive programs and services to South King County, where time Emily graduated from pre-school, Financial Empowerment Program 5 56% of King County’s Latino community lives. her social/emotional development and • Extending aging services, support, outreach, connection, and social engagement all day Success Stories academic performance were outstanding. for isolated seniors known as the El Centro de la Raza Senior Hub. -

Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2006 The struggle for dignity: Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000 James Michael Slone University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Slone, James Michael, "The struggle for dignity: Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000" (2006). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2086. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/4kwz-x12w This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STRUGGLE FOR DIGNITY: MEXICAN-AMERICANS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, 1900-2000 By James Michael Slone Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in History Department of History College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1443497 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

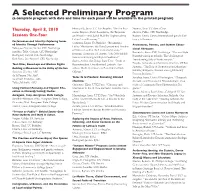

A Selected Preliminary Program (A Complete Program with Date and Time for Each Panel Will Be Available in the Printed Program)

(Devon G. Peña, Ph.D.) continued from page 16 The NACCS Executive Board, officers, We expect this work will strengthen “Fighting Pollution from the Ground and conference organizers are proud to our community-based struggles for a Up.” This session will feature grassroots present such a wide range of perspec- world yearning to break through the youth activists from Communities for tives on environmental and food justice. greed and destructiveness of the neo- a Better Environment (CBE) and Youth We anticipate that this year our confer- liberal age that we seek to end through EJ/CBE/Southwest Network for Envi- ence activities will extend outward to this celebration and empowerment of ronmental and Economic Justice. the farms, gardens, workplaces, and brown-green activism and social change homes that share our hunger and thirst scholarship. n for environmental and food justice. A Selected Preliminary Program (a complete program with date and time for each panel will be available in the printed program) Thursday, April 8, 2010 Hermosillo, Jesus. UC Los Angeles. “On the Eco- Zepeda, Susy. UC Santa Cruz. nomic Impact of LA’s Loncheras, the Taquerias Alvarez, Pablo. CSU Northridge. Sessions One-Four on Wheels---and Social Mobility Engines of the Roman, Estela. Centro Internacional para la Cul- Latino Local Economy.” tura y la Enseñza. Performance and Identity: Exploring Issues Gutierrez, Livier. UC Berkeley. “Becoming a of Identity Through Performance Promotoras, Parents, and Student Educa- Latino Minuteman: the Development and Practice Velazquez Vargas, Yarma. CSU Northridge. tional Advocates of Nativism within the Latino Community.” Sanchez-Tello, George. CSU Northridge. Furumoto, Rosa. -

This Is the Cover

Mcnair scholars journal ____________________________________________________________________________________________ The McNair Scholars Journal of the University of Washington Volume VII Spring 2008 ii THE MCNAIR SCHOLARS JOURNAL UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON McNair Program Office of Minority Affairs University of Washington 375 Schmitz Hall Box 355845 Seattle, WA 98195-5845 [email protected] http://depts.washington.edu/uwmcnair The Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program operates as a part of TRIO Programs, which are funded by the U.S. Department of Education. i Mcnair scholars journal ____________________________________________________________________________________________ University of Washington McNair Program Staff Program Director Gabriel Gallardo, Ph.D. Associate Director Gene Kim, Ph.D. Program Coordinator Rosa Ramirez Graduate Student Advisors Zakiya Adair Eric Hilton Rocio Mendoza McNair Scholars’ Research Mentors Dr. Richard Anderson, Computer Science and Engineering Dr. Gad Barzilai, International Studies Dr. Pamela Conrad, Astrobiology (NASA Jet Propulsion Lab) Dr. Oren Etzioni, Computer Science and Engineering Dr. Mark Forehand, Marketing Dr. James Gregory, History Dr. Gregory Jensen, Aquatic and Fishery Science Dr. Peter Pecora, Social Work Dr. Nikhil Singh,History Dr. Alys Weinbaum, English Dr. Joseph Weis, Sociology Volume VII Copyright 2008 ii From the Dean of the Graduate School It is with real pleasure that I write to introduce this seventh volume of The McNair Scholars Journal. The papers contained in this volume represent a remarkable breadth of scholarship. They also represent a depth of scholarship that encompasses the best of what the University of Washington has to offer. The Scholars, their faculty mentors, the staff of the McNair Program, and all of us at this institution are justifiably proud of this work. -

Citizen Review of Police : Approaches and Implementation

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Issues and Practices U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij Citizen Review of Police: Approaches and Implementation by Peter Finn March 2001 NCJ 184430 National Institute of Justice Vincent Talucci Program Monitor Advisory Panel* K. Felicia Davis, J.D. Douglas Perez, Ph.D. Samuel Walker, Ph.D. Legal Consultant and Director Assistant Professor Kiewit Professor at Large Department of Sociology Department of Criminal Justice National Association for Civilian Plattsburgh State University University of Nebraska Oversight of Law Enforcement 45 Olcott Lane at Omaha Rensselaer, NY 12144 60th and Dodge Streets Administrator Omaha, NE 68182 Citizen Review Board Jerry Sanders 234 Delray Avenue President and Chief Lt. Steve Young Syracuse, NY 13224 Executive Officer Vice President United Way of San Diego Grand Lodge Mark Gissiner County Fraternal Order of Police Senior Human Resources Analyst P.O. Box 23543 222 East Town Street City of Cincinnati San Diego, CA 92193 Columbus, OH 43215 Immediate Past President, 1995–99 Former Chief International Association for San Diego Police Department Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement 2665 Wayward Winds Drive Cincinnati, OH 45230 *Among other criteria, advisory panel members were selected for their diverse views regarding citizen oversight of police. As a result, readers should not infer that panel members necessarily support citizen review in general or any particular type of citizen review.