Chapter 13 Individual Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A-4E Finds New Home Tasked with Transferring the Craft

7!1 7 Vol. 24, No. 6 Serving Marine Forces Pacific, MCB Hawaii, Ill Marine Expeditionary Forces, Hawaii and 1st Radio Battalion February 15, 1996 A-4E finds new home tasked with transferring the craft. It LC,p1. Steven Williams is the only unit in Hawaii with heavy-lift capability. The other mili- The Aviation Support Element and tary installations on the island don't Combat Service Support Group-3 have the aircraft to lift the jet, aboard MCB Hawaii teamed up according to Maj. Jesse E. Wrice, Monday to transfer a 7,000-pound ASE operations officer. Douglas A-4E Skyhawk from Naval The six leaders in the transfer pro- Air Station Barbers Point to ject surveyed the jet Jan. 22. to Dillingham Air Field. ensure the aircraft was safe to move. The aircraft was donated to the "We did all of our homework in Find what's got the dolphins Hawaiian Historical Aviation January so it would run smoothly in jumping. See B-1 for story. Foundation, a non-profit organiza- February," said Wrice. tion, Sept. 19 by the Navy's Fleet Before it was transferred, the jet's Composite Squadron 1. The nose gear door was removed and the Great Aloha Run squadron decommissioned in tail hook was dropped. Dropping the September 1993 leaving most of its tail hook allowed the belly bands to transportation aircraft to the National Naval sit flesh on the aircraft's stomach. Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Fla. The team also added 400 to 600 The 12th annual Great Aloha Following the down-size, HHAF put pounds of weight to the nose of the Run will be held Monday at 7 a.m. -

Very Vintage for Golf Minded Women

PAST CHAMPIONS Year Champion Year Champion 1952 Jean Perry 1982 Lynn Chapman 1953 Joanne Gunderson 1983 Lil Schmide 1954 Joanne Gunderson 1984 Sue Otani 1955 Jean Thorpen 1985 Sue Otani 1956 Jenny Horne 1986 Cathy Daley 1957 Becky Brady 1987 Ann Carr 1958 Mary Horton 1988 Brenda Cagle 1959 Joyce Roberts. 1989 Michelle Campbell 2012 GSWPGA City 1960 Mildred Barter 1990 Linda Rudolph 1961 Joyce Roberts 1991 Gerene Lombardini 1962 Pat Reeves 1992 Rachel Strauss Championship 1963 Pat Reeves 1993 Janet Best 1964 Joyce Roberts 1994 Rachel Strauss August 6, 7, & 8 1965 Mary Ann George 1995 Deb Dols 1966 Olive Corey 1996 Jennifer Ederer Hosted by Auburn Ladies Club 1967 Borgie Bryan 1997 Jennifer Ederer 1968 Fran Welke 1998 Sharon Drummey 1969 Fran Welke 1999 Rachel Strauss at Auburn Golf Course 1970 Carole Holland 2000 Rachel Strauss 1971 Edee Layson 2001 Marian Read 1972 Anita Cocklin 2002 Rachel Strauss 1973 Terri Thoreson 2003 Rachel Strauss Very Vintage 1974 Carole Holland 2004 Mimi Sato 1975 Carole Holland 2005 Rachel Strauss 1976 Carole Holland 2006 Rachel Strauss 1977 Chris Aoki 2007 Janet Dobrowolski 2008 Rachel Strauss For Golf Minded 1978 Jani Japar 1979 Carole Holland 2009 Rachel Strauss 1980 Lisa Porambo 2010 Cathy Kay 1981 Karen Hansen 2011 Mariko Angeles Women In honor of the Legends Tour participants in the July 29, 2012 event at Inglewood Golf and CC and past women contributors to the game of golf, we are naming the tee boxes for this tournament: Hole #1: JoAnne Carner Hole #10: Nancy Lopez Hole #2: Patty Sheehan Hole #11: Jan Stephenson Hole #3: Lori West Hole #12: Dawn Coe-Jones Hole #4: Elaine Crosby Hole #13: Patti Rizzo To view more GSWPGA History, visit: Hole #5: Shelley Hamlin Hole #14: Elaine Figg-Currier http://www.gswpga.com/museum.htm Hole #6: Jane Blalock Hole #15: Val Skinner For information about the Legends Tour event at Inglewood Golf and CC Hole #7: Sandra Palmer Hole #16: Rosie Jones July 29th, 2012, visit: thelegendstour.com/tournaments_2012_SwingforCure_Seattle Hole #8: Sherri Turner Hole #17: Amy Alcott on the web. -

FOR SHORE the LPGA Tournament Now Known As the ANA Inspiration Has a Rich History Rooted in Celebrity, Major Golf Milestones, and One Special Leap

DRIVING AMBITION In the inaugural tournament bearing her name, Dinah Shore was reportedly more concerned about her “golfing look” than her golfing score. Opposite: In 1986, the City of Rancho Mirage honored the entertainer by naming a street after her. Dinah’s Place, FOR SHORE The LPGA tournament now known as the ANA Inspiration has a rich history rooted in celebrity, major golf milestones, and one special leap. by ROBERT KAUFMAN photography from the PALM SPRINGS LIFE ARCHIVES NE OF THE MOST SERENDIPITOUS Palmolive. Already a mastermind at selling toothpaste and soaps, Foster moments in the history of women’s professional recognized women’s golf as a platform ripe for promoting sponsors — but if golf stems from the day Frances Rose “Dinah” the calculating businessman were to roll the dice, the strategy must provide Shore entered the world. In a twist of fate just a handsome return on the investment. over a half century following leap day, Feb. 29, During this era, famous entertainers, including Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, 1916, the future singer, actress, and television Andy Williams, and Danny Thomas, to name a few, were already marquee personality would emerge as a major force names on PGA Tour events. Without any Hollywood influence on the LPGA behind the women’s sport, leaping into a Tour, Foster enlisted his A-list celebrity, Dinah Shore, whose daytime talk higher stratosphere with the birth of the Colgate-Dinah Shore Winner’s show “Dinah’s Place” was sponsored by Colgate-Palmolive, Circle Oin 1972. to be his hostess. The top-charting female vocalist While it may have taken 13 tenacious female golfers — the likes of Babe of the 1940s agreed. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE For Release: Monday, August 16, 2004 Ticket Info: www.saschampionship.com or 1-800-531-7PGA (7742) Contact: Chris Madigan, [email protected] or (203) 352-6325 TOM KITE COMMITS TO SAS CHAMPIONSHIP PRESENTED BY FORBES CARY, N.C. – Tournament officials for the SAS Championship presented by Forbes announced today that 1992 U.S. Open winner Tom Kite intends to play in the fourth annual SAS Championship. The SAS Championship, an official event on the Champions Tour, returns to Prestonwood Country Club, September 20-26. Kite, a 19-time PGA TOUR winner, has seven Champions Tour victories in his four years on Tour. His most recent win came eight days ago at the 3M Championship when he sank three birdies in the last seven holes to win by one stroke over Craig Stadler, also committed to the SAS Championship field. Kite has seven other top-10 finishes this year. His victory at the 3M Championship ended a winless streak dating back to October 2002 and spanning 47 tournaments where he finished in second place six times. One of those second place finishes was last year’s SAS Championship. Kite recorded a career best single-round score of 61 at Prestonwood Country Club during Sunday’s final round, vaulting him from 34th place into a second place finish behind D.A. Weibring. “Tom made an incredible run at last year’s title, posting a score early, creating the stage for an incredibly dramatic finish,” said Jeff Kleiber, tournament director. “He’s one of the best golfers that’s ever played the game. -

Movember Set to Improve Men's Health This November

MOVEMBER SET TO IMPROVE MEN’S HEALTH THIS NOVEMBER AT THE MELBOURNE WORLD CUP OF GOLF 21 June, 2018: To help raise much needed funds, and awareness of men’s health issues, the Movember Foundation will come in swinging following their appointment as the official charity of the Melbourne World Cup of Golf, to be held at The Metropolitan Golf Club from the 21-25 November 2018. And with players from 28 nations descending on Melbourne for the event, the opportunity exists for players and fans to sport a traditional national mo to support the cause and get involved. The Movember Foundation has one goal: to stop men dying too young. As the only global charity tackling men’s health issues year-round, the Foundation funds programs tackling prostate cancer, testicular cancer, mental health and suicide prevention. In 2018, more than 1.4 million men globally will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. Three out of every four suicides are men and, in Australia, testicular cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men between the ages of 20 and 34. With those statistics, Melbourne World Cup of Golf Executive Director Robyn Cooper says the Movember Foundation is the perfect fit for the tournament. “We are proud to be able to support a global charity that was born in Melbourne,” Cooper said. “Approximately 75% of the world’s golfers are male and from Craig "The Walrus" Stadler to John Daly and our own Geoff Ogilvy to legendary caddie Mike "Fluff" Cowen, the moustache has long been the trademark of the stylish pro golfer.” The PGA TOUR has been a strong supporter of the moustache, with the Web.com Tour conducting the annual Moustache Madness contest at the Utah Championships every July. -

Candidate Brief

Candidate Brief Brief for the position of Chief Executive Officer, PGA European Tour February 2015 Candidate Brief, February 2015 2 Chief Executive Officer, PGA European Tour Contents Welcome from the Chairman ................................................................................................................. 3 Summary......................................................................................................................................................... 4 The PGA European Tour........................................................................................................................... 5 Constitution and governance ............................................................................................................... 11 Role profile .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Selection criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 16 Principal challenges ................................................................................................................................. 17 Remuneration ............................................................................................................................................. 17 Search process ........................................................................................................................................... -

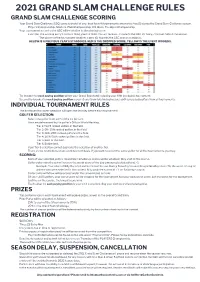

2021 Grand Slam Challenge Rules

2021 GRAND SLAM CHALLENGE RULES GRAND SLAM CHALLENGE SCORING Your Grand Slam Challenge (GSC) score is a total of your best four (4) tournaments among the five (5) during the Grand Slam Challenge season. Players Championship, Masters, PGA Championship, U.S. Open, The Open Championship Your tournament score for the GSC will be relative to the winning score. Example: The winning entry’s score is 1422, yours is 1429. You will receive -7 towards the GSC for being 7 strokes behind the winner. The winner of the tournament receives a zero (0) towards the GSC season standings. BELOW IS A PREVIOUS YEAR’S STANDINGS. RED IS THE DROPPED SCORE, YELLOW IS THE EVENT WINNERS. Tie-breaker for each paying position will be your Grand Slam total including your fifth (excluded) tournament. Second tie-breaker for each paying position is your Grand Slam total including your sixth (excluded) golfers from all tournaments. INDIVIDUAL TOURNAMENT RULES The dashboard for golfer selection will open the Monday before each tournament. GOLFER SELECTION: Select one golfer from each of the six (6) tiers. Tiers are determined by the golfer’s Official World Ranking. Tier 1: Top 5 ranked golfers in the field. Tier 2: 6th-15th ranked golfers in the field. Tier 3: 16th-25th ranked golfers in the field. Tier 4: 26th-50th ranked golfers in the field. Tier 5: Rest of the field. Tier 6. Entire field. Your Tier 6 selection cannot duplicate the selection of another tier. There are no restrictions on an event to event basis. If you want to select the same golfer for all five tournaments, you may. -

2020 Women’S Tennis Association Media Guide

2020 Women’s Tennis Association Media Guide © Copyright WTA 2020 All Rights Reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying- without the written permission of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Compiled by the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Communications Department WTA CEO: Steve Simon Editor-in-Chief: Kevin Fischer Assistant Editors: Chase Altieri, Amy Binder, Jessica Culbreath, Ellie Emerson, Katie Gardner, Estelle LaPorte, Adam Lincoln, Alex Prior, Teyva Sammet, Catherine Sneddon, Bryan Shapiro, Chris Whitmore, Yanyan Xu Cover Design: Henrique Ruiz, Tim Smith, Michael Taylor, Allison Biggs Graphic Design: Provations Group, Nicholasville, KY, USA Contributors: Mike Anders, Danny Champagne, Evan Charles, Crystal Christian, Grace Dowling, Sophia Eden, Ellie Emerson,Kelly Frey, Anne Hartman, Jill Hausler, Pete Holtermann, Ashley Keber, Peachy Kellmeyer, Christopher Kronk, Courtney McBride, Courtney Nguyen, Joan Pennello, Neil Robinson, Kathleen Stroia Photography: Getty Images (AFP, Bongarts), Action Images, GEPA Pictures, Ron Angle, Michael Baz, Matt May, Pascal Ratthe, Art Seitz, Chris Smith, Red Photographic, adidas, WTA WTA Corporate Headquarters 100 Second Avenue South Suite 1100-S St. Petersburg, FL 33701 +1.727.895.5000 2 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Women’s Tennis Association Story . 4-5 WTA Organizational Structure . 6 Steve Simon - WTA CEO & Chairman . 7 WTA Executive Team & Senior Management . 8 WTA Media Information . 9 WTA Personnel . 10-11 WTA Player Development . 12-13 WTA Coach Initiatives . 14 CALENDAR & TOURNAMENTS 2020 WTA Calendar . 16-17 WTA Premier Mandatory Profiles . 18 WTA Premier 5 Profiles . 19 WTA Finals & WTA Elite Trophy . 20 WTA Premier Events . 22-23 WTA International Events . -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Recreational League Guide TABLE of CONTENTS

Recreational League Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME FROM BILLIE JEAN KING . 3 JOIN THE WINNING TEAM Mylan World TeamTennis . .4 . Mylan WTT Recreational League . 4 . RECREATIONAL LEAGUE SPONSORS . 4. ADDITIONAL MYLAN WTT PROGRAMS . 4-5 MYLAN WTT RECREATIONAL LEAGUES What Is It? . .5 . Who Plays? . 5 . When Can Your League Start? . .5 . How Does Mylan WTT Help the Tennis Club or Public Facility? . 5 Mylan WTT Membership Includes . 5 What is Needed? . 6 . Can Teams Advance Past the Local Level? . 6 . Can Seniors Participate? . 6. Can Open Players Participate? . .6 . SCORING Game Scoring . 6 Set Scoring . 6 . Match Scoring and Overtime . 7. Substitutions . 7 . Warm-up Time . 7. Service Order . 7. Changing Ends . 7. Service Lets . 7 Coaching/Line Calls . 7 Default Rule . 8 Explanation of Tiebreakers . 8 . ADMINISTRATION OF LEAGUES Team Captain . 9 League Director . 9-10 Licensing your League or Tournament . 10 . Fee Structure for a Mylan WTT League or Tournament Site License . 10-11 . Handling the Cost of the League . .11 . Tennis Balls . .11 . PUBLICITY How to Get Publicity . 12. Respecting Media Deadlines . 12 . Using Media Kits . 13. Leverage the Power of Social Networking . 13 TIPS FOR RECRUITING CORPORATE TEAMS . 14. SAMPLE NEWS RELEASES 866-PLAY-WTT | WTT.COM — 1 — MYLAN WTT RECREATIONAL LEAGUE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS [CONTINUED] Mylan WTT Recreational League . .15 . Mylan WTT Corporate League . 16 MYLAN WTT RECREATIONAL LEAGUE STYLE GUIDE - PUBLIC RELATIONS Mylan WTT References - Capitalization . 17. Correct Name of Other Mylan WTT Events and Affiliated Events . 17 . USTA National Campus Championships . 17 Mylan WTT Boilerplate . .17 . Mylan WTT Logo . 17. HOW TO SET UP A ROUND ROBIN SCHEDULE . -

Glossary of Tennis Terms

Glossary of Tennis Terms • A o Ace: a service point won by the server because the receiver doesn’t return, or even touch, the ball. Advantage (or ad) court: left-hand side of the court. o Advantage (or Ad): the point played after deuce, which if won, ends the game. o Advantage set: a set that can only be won when one opponent has won six games and is two games clear of their opponent. o All: term used when both players have the same number of points from 15-15 (15-all) to 30- 30 (30-all). When the score is 40-40 the term is deuce. o All-court player: someone who is equally comfortable playing from the baseline, mid-court and net. o Alley: (see tramlines.) o Approach shot: a shot used by a player to pin their opponent behind the baseline so that they can run to the net for a volley. • B o Back court: area behind the court between the baseline and the back fence. o Backhand: shot struck by holding the racquet in the dominant hand but swinging the racquet from the non-dominant side of the body with the back of the dominant hand pointing in the direction the ball is being hit. (See also two-handed backhand.) o Backspin: spin imparted on the underside of the ball causing it to revolve backwards while travelling forwards. Used in slice and drop shots. o Backswing: component of the swing where the racquet is taken back behind the body in preparation for the forward motion that leads to contact with the ball. -

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest for Perfection

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER New Chapter Press Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic Originally published in Germany under the title “Das Tennis-Genie” by Pendo Verlag. © Pendo Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich and Zurich, 2006 Published across the world in English by New Chapter Press, www.newchapterpressonline.com ISBN 094-2257-391 978-094-2257-397 Printed in the United States of America Contents From The Author . v Prologue: Encounter with a 15-year-old...................ix Introduction: No One Expected Him....................xiv PART I From Kempton Park to Basel . .3 A Boy Discovers Tennis . .8 Homesickness in Ecublens ............................14 The Best of All Juniors . .21 A Newcomer Climbs to the Top ........................30 New Coach, New Ways . 35 Olympic Experiences . 40 No Pain, No Gain . 44 Uproar at the Davis Cup . .49 The Man Who Beat Sampras . 53 The Taxi Driver of Biel . 57 Visit to the Top Ten . .60 Drama in South Africa...............................65 Red Dawn in China .................................70 The Grand Slam Block ...............................74 A Magic Sunday ....................................79 A Cow for the Victor . 86 Reaching for the Stars . .91 Duels in Texas . .95 An Abrupt End ....................................100 The Glittering Crowning . 104 No. 1 . .109 Samson’s Return . 116 New York, New York . .122 Setting Records Around the World.....................125 The Other Australian ...............................130 A True Champion..................................137 Fresh Tracks on Clay . .142 Three Men at the Champions Dinner . 146 An Evening in Flushing Meadows . .150 The Savior of Shanghai..............................155 Chasing Ghosts . .160 A Rivalry Is Born .