Ambedkar Will Teach the Nation from His Statues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues in Indian Politics –

ISSUES IN INDIAN POLITICS – Core Course of BA Political Science - IV semester – 2013 Admn onwards 1. 1.The term ‘coalition’ is derived from the Latin word coalition which means a. To merge b. to support c. to grow together d. to complement 2. Coalition governments continue to be a. stable b. undemocratic c. unstable d. None of these 3. In coalition government the bureaucracy becomes a. efficient b. all powerful c. fair and just d. None of these 4. who initiated the systematic study of pressure groups a. Powell b. Lenin c. Grazia d. Bentley 5. The emergence of political parties has accompanied with a. Grow of parliament as an institution b. Diversification of political systems c. Growth of modern electorate d. All of the above 6. Party is under stood as a ‘doctrine by a. Guid-socialism b. Anarchism c. Marxism d. Liberalism 7. Political parties are responsible for maintaining a continuous connection between a. People and the government b. President and the Prime Minister c. people and the opposition d. Both (a) and (c) 1 8. The first All India Women’s Organization was formed in a. 1918 b. 1917 c.1916 d. 1919 9. ------- belong to a distinct category of social movements with the ideology of class conflict as their basis. a. Peasant Movements b. Womens movements c. Tribal Movements d. None of the above 10.Rajni Kothari prefers to call the Indian party system as a. Congress system b. one party dominance system c. Multi-party systems d. Both a and b 11. What does DMK stand for a. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

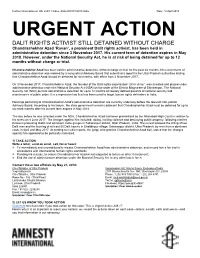

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

25 May 2018 Hon'ble Chairperson, Shri Justice HL

25 May 2018 Hon’ble Chairperson, Shri Justice H L Dattu National Human Rights Commission, Block –C, GPO Complex, INA New Delhi- 110023 Respected Hon’ble Chairperson, Subject: Continued arbitrary detention and harassment of Dalit rights activist, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravana The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) appeals the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to urgently carry out an independent investigation into the continued detention of Dalit human rights defender, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh State, to furnish the copy of the investigation report before the non-judicial tribunal established under the NSA, and to move the court to secure his release. Chandrashekhar is detained under the National Security Act (NSA) without charge or trial. FORUM-ASIA is informed that in May 2017, Dalit and Thakur communities were embroiled in caste - based riots instigated by the dominant Thakur caste in Saharanpur city of Uttar Pradesh. The riots resulted in one death, several injuries and a number of Dalit homes being burnt. Following the protests, 40 prominent activists and leaders of 'Bhim Army', a Dalit human rights organisation, were arrested but later granted bail. Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, a young lawyer and co-founder of ‘Bhim Army’, was arrested on 8 June 2017 following a charge sheet filed by a Special Investigation Team (SIT) constituted to investigate the Saharanpur incident. He was framed with multiple charges under the Indian Penal Code 147 (punishment for rioting), 148 (rioting armed with deadly weapon) and 153A among others, for his alleged participation in the riots. Even though Chandrashekhar was not involved in the protests, and wasn't present during the riot, he was detained on 8 June. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=4... Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada India: Treatment of Dalits by society and authorities; availability of state protection (2016- January 2020) 1. Overview According to sources, the term Dalit means "'broken'" or "'oppressed'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). Sources indicate that this group was formerly referred to as "'untouchables'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). They are referred to officially as "Scheduled Castes" (India 13 July 2006, 1; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). The Indian National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) identified that Scheduled Castes are communities that "were suffering from extreme social, educational and economic backwardness arising out of [the] age-old practice of untouchability" (India 13 July 2006, 1). The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) [1] indicates that the list of groups officially recognized as Scheduled Castes, which can be modified by the Parliament, varies from one state to another, and can even vary among districts within a state (CHRI 2018, 15). According to the 2011 Census of India [the most recent census (World Population Review [2019])], the Scheduled Castes represent 16.6 percent of the total Indian population, or 201,378,086 persons, of which 76.4 percent are in rural areas (India 2011). The census further indicates that the Scheduled Castes constitute 18.5 percent of the total rural population, and 12.6 percent of the total urban population in India (India 2011). -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

'Dr. Ambedkar Jayanti' on 14.04.2020 - Reg' 20L9 and Subsequent This Is Regarding Celebration of Constitution Day on 26Th November, Activities Culminating in 'Dr

qferur *flffq irfrfr a 8. Southern Regional Committee qRq-q National Council fsr Teacher Education rr$q sIErIFro ftrerr L\ng, (ttrd s{trn irl v{ frft6 rfte{H) (A Statutory Body of the Government of lndia) nw@ um NETE Date- 11l11 File No. - SRc/NCTE/Misc./lTl002 /2OI9 To, All Teachers Educational Institutions activities culminating in sub: - cefebration of constitution Day on 26.rt.2019 and subsequent 'Dr. Ambedkar Jayanti' on 14.04.2020 - reg' 20L9 and subsequent This is regarding Celebration of Constitution day on 26th November, activities culminating in 'Dr. Ambedkar JaVanti' on L4'n April, 2020:- the following All the TEts recognised by the NCTE are requested to kindly undertake Dr' Ambedkar activities starting from constitution Day (26.11.2019) and culminating in Duties' Jayanti/Samrasta Divas (I4.4.2O2O) with greater focus on Fundamental 28.L7.2019 - 29.LL.20r9 Debates, cultural Programmes, qulz competitions seminars and lecturer be organized bY TEls. 06.01.2020 - 27 .01.2020 Essay com petition on "Constitution AllTEls and Fundamental Duties" to be nized within the TEls 03.02.2020 - LO.O2.2020 Organized Mock Parliament. AllTEls 31..72.20L9 Public messages of Fundamental Duties for dissemination among students and staff during the celebrations. Invite eminent personalities from 1.4.O4.2020 (Dr. Ambedkar JaYanti) different walks of life to disseminate the massage of Fundamental Duties. to the Regional Director, The TEls are requested to kindly furnish the Action Taken Report SRC, NCTE through email: [email protected]'org' ' ,$ Y-/t Dr. -

Joint Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Adoption of List of Issues

JOINT SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, ADOPTION OF LIST OF ISSUES 126TH SESSION, (01 to 26 July 2019) JOINTLY SUBMITTED BY NATIONAL DALIT MOVEMENT FOR JUSTICE-NDMJ (NCDHR) AND INTERNATIONAL DALIT SOLIDARITY NETWORK-IDSN STATE PARTY: INDIA Introduction: National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ)-NCDHR1 & International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) provide the below information to the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee (the Committee) ahead of the adoption of the list of issues for the 126th session for the state party - INDIA. This submission sets out some of key concerns about violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the Covenant) vis-à- vis the Constitution of India with regard to one of the most vulnerable communities i.e, Dalit's and Adivasis, officially termed as “Scheduled Castes” and “Scheduled Tribes”2. Prohibition of Traffic in Human Beings and Forced Labour: Article 8(3) ICCPR Multiple studies have found that Dalits in India have a significantly increased risk of ending in modern slavery including in forced and bonded labour and child labour. In Tamil Nadu, the majority of the textile and garment workforce is women and children. Almost 60% of the Sumangali workers3 belong to the so- called ‘Scheduled Castes’. Among them, women workers are about 65% mostly unskilled workers.4 There are 1 National Dalit Movement for Justice-NCDHR having its presence in 22 states of India is committed to the elimination of discrimination based on work and descent (caste) and work towards protection and promotion of human rights of Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) across India. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

CURRENT AFFAIRS August 2020

1 | P a g e CURRENT AFFAIRS August 2020 Copyright © by Classic IAS Academy All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without www.classiciasacademy.comprior permission of Classic IAS Academy. 2 | P a g e CONTENTS 1. LOKMANYA TILAK'S 100TH DEATH 18. 150TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY OF ANNIVERSARY ABANINDRANATH TAGORE 2. KHARIF CROPS OF INDIA 19. LIST OF DEFENCE PUBLIC SECTOR UNDERTAKINGS IN INDIA 3. PRODUCTION LINKED INCENTIVE SCHEME (PLI) 20. DIAT WINS FIRST PRIZE IN SMART INDIA HACKATHON-2020 4. PAN INDIA 1000 GENOME SEQUENCING OF SARS- COV-2 21. FERTILIZER MONITORING SYSTEMS 5. KHADI AGARBATTI AATMANIRBHAR 22. HIGH-SPEED BROADBAND MISSION CONNECTIVITY FOR ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 6. CATARACT 23. TRIFED 7. DRAFT DEFENCE PRODUCTION AND EXPORT PROMOTION POLICY 2020 24. ODF PLUS 8. ELECTRONIC VACCINE INTELLIGENCE 25. SHRI G C MURMU: C&AG OF INDIA NETWORK (eVIN) 26. LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITIES ACT, 9. PHASE II+III TRIALS OF OXFORD 1987 UNIVERSITY VACCINE 27. AGRICULTURE INFRASTRUCTURE FUND 10. TYPES OF FOREIGN INVESTMENT IN 28. eSANJEEVANI INDIA 29. IMPORTANT PARLIAMENTARY TERMS 11. DEKHO APNA DESH SCHEME 2020 30. NORMALIZED DIFFERENCE 12. BASIS FOR CONTEMPT OF COURT VEGETATION INDEX 13. PMGKAY-2 31. REMOTE VOTING 14. NATIONAL CYBER COORDINATION 32. KRISHI MEGH CENTRE (NCCC) 33. PM SVANidhi SCHEME 15. NETRA (NEtwork TRaffic Analysis) 34. PARAMPARAGAT KRISHI VIKAS 16. 2020 BEIRUT EXPLOSION YOJANA 17. INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE (ICH) 35. ORGANIC FARMING www.classiciasacademy.com 3 | P a g e 36.