Topic 14: RAINFORESTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Frost Suceptable Native Species

1 FROST HARDINESS Some people have attempted to make a rudimentary assessment of frost hardy species as illustrated in the table below. Following the severe frosts of 27-7-07, Initial observations are on the foliage “burn” and it remains to be seen whether the stems/trunks die or merely re-shoot. Note: * = Exotic; # = Not native to the area; D = dead; S = survived but only just e.g. sprouting lower down; R = recovering well Very Susceptible Species Common Name Notes Alphitonia excelsa red ash R Alphitonia petriei pink ash R Annona reticulata custard apple S Archontophoenix alexandrae# Alexander palm D, R Asplenium nidus bird’s nest fern R,S Beilschmiedia obtusifolia blush walnut Calliandra spp.* S,R Cassia brewsteri Brewster’s cassia R Cassia javanica* S Cassia siamea* S Citrus hystrix* Kaffir lime S,D Clerodendrum floribundum lolly bush R,S Colvillea racemosa* Colville’s glory R Commersonia bartramia brown kurrajong S,R Cordyline petiolaris tree lily R Cyathea australis common treefern R Delonix regia* R Elaeocarpus grandis silver quandong D,S Eugenia reinwardtiana beach cherry S Euroschinus falcata pink poplar, mangobark, R ribbonwood, blush cudgerie Ficus benjamina* weeping fig S Ficus obliqua small-leaved fig S Flindersia bennettiana Bennett’s ash Harpullia pendula tulipwood R Harpullia hillii blunt-leaved tulipwood Hibiscus heterophyllus native hibiscus S Jagera pseudorhus pink foambark R Khaya anthotheca* E African mahogany R Khaya senegalensis* W African mahogany R Koelreuteria paniculata* Chinese golden shower tree R Lagerstroemia -

A4 Template with Cover and Following Page

Powerful Owl Project Update – December 2015 Caroline Wilson, Holly Parsons & Janelle Thomas Thank-you to all of you for being involved with another successful year of the Powerful Owl Project. We had some changes this year, with our main grant funding finishing Caroline Wilson and Janelle Thomas from the Threatened Bird Network (TBN) and Holly Parsons from the Birds in Backyards Program took over the running of the project for BirdLife Australia. Generous donations from the NSW Twitch-a-thon has allowed us to complete this year’s research and allows us to continue in 2016. This season we have had over 120 registered volunteers involved, including over 50 new volunteers who were recruited to the project early this year. You have helped us monitor over 80 Powerful Owl breeding sites, allowing the project to cover a lot of ground throughout Greater Sydney, the NSW Central Coast and Newcastle. The data you have collected is really important for the effective management of urban Powerful Owl populations and this information is shared with land mangers and local councils. So thank-you! We really appreciate the amazing work carried out by our volunteers; with your help we have learned so much about these birds, and this information is helping us protect this unique and amazing species. Read on to hear about all we have achieved in 2015. Powerful Owl chick from 2015, peeking out of the hollow (taken by Christine Melrose) March 2015 workshop The March workshop was held to train our new volunteers, update everyone on the findings from the project and to say thank-you to our existing volunteers – some of which have been with us since 2011. -

An Infrageneric Classification of Syzygium (Myrtaceae)

Blumea 55, 2010: 94–99 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE doi:10.3767/000651910X499303 An infrageneric classification of Syzygium (Myrtaceae) L.A. Craven1, E. Biffin 1,2 Key words Abstract An infrageneric classification of Syzygium based upon evolutionary relationships as inferred from analyses of nuclear and plastid DNA sequence data, and supported by morphological evidence, is presented. Six subgenera Acmena and seven sections are recognised. An identification key is provided and names proposed for two species newly Acmenosperma transferred to Syzygium. classification molecular systematics Published on 16 April 2010 Myrtaceae Piliocalyx Syzygium INTRODUCTION foreseeable future. Yet there are many rewarding and worthy floristic and other scientific projects that await attention and are Syzygium Gaertn. is a large genus of Myrtaceae, occurring from feasible in the shorter time frame that is a feature of the current Africa eastwards to the Hawaiian Islands and from India and research philosophies of short-sighted institutions. southern China southwards to southeastern Australia and New One impediment to undertaking studies of natural groups of Zealand. In terms of species richness, the genus is centred in species of Syzygium, as opposed to floristic studies per se, Malesia but in terms of its basic evolutionary diversity it appears has been the lack of a framework or context within which a set to be centred in the Melanesian-Australian region. Its taxonomic of species can be the focus of specialised research. Below is history has been detailed in Schmid (1972), Craven (2001) and proposed an infrageneric classification based upon phylogenies Parnell et al. (2007) and will not be further elaborated here. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

The Wood Cross Sections of Hermann Nördlinger (1818–1897)

IAWA Journal, Vol. 29 (4), 2008: 439–457 THE WOOD CROSS SECTIONS OF HERMANN NÖRDLINGER (1818–1897) Ben Bubner Leibniz-Zentrum für Agrarlandschaftsforschung (ZALF) e.V., Institut für Landschaftsstoffdynamik, Eberswalder Str. 84, 15374 Müncheberg, Germany [E-mail: [email protected]] SUMMARY Hermann Nördlinger (1818–1897), forestry professor in Hohenheim, Germany, published a series of wood cross sections in the years 1852 to 1888 that are introduced here to the modern wood anatomist. The sec- tions, which vary from 50 to 100 μm in thickness, are mounted on sheets of paper and their quality is high enough to observe microscopic details. Their technical perfection is as remarkable as the mode of distribution: sections of 100 wood species were presented in a box together with a booklet containing wood anatomical descriptions. These boxes were dis- tributed as books by the publisher Cotta, from Stuttgart, Germany, with a maximum circulation of 500 per volume. Eleven volumes comprise 1100 wood species from all over the world. These include not only conifers and broadleaved trees but also shrubs, ferns and palms representing a wide variety of woody structures. Excerpts of this collection were also pub- lished in Russian, English and French. Today, volumes of Nördlingerʼs cross sections are found in libraries throughout Europe and the United States. Thus, they are relatively easily accessible to wood anatomists who are interested in historic wood sections. A checklist with the content of each volume is appended. Key words: Cross section, wood collection, wood anatomy, history. INTRODUCTION Wood scientists who want to distinguish wood species anatomically rely on thin sec- tions mounted on glass slides and descriptions in books that are illustrated with micro- photographs. -

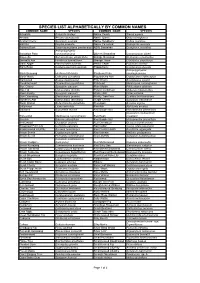

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Final Report

FINAL REPORT Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Gippsland Region, March 2002 1 © The State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources and Environment 2002. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, or graphic) without written prior permission of the State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources and Environment. All requests and enquires should be directed to the Copyright Officer, Library Information Services, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, 5/250 Victoria Parade, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002. ISBN 1 74106 548 8 Find more information about the Department at www.dse.vic.gov.au Customer Service Centre Phone: 136 186 [email protected] General disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequences which may arise from your relying on information in this publication. COVER PHOTO LOCATIONS (TOP TO BOTTOM) Photo 1. Depauperate Coastal Tussock Grassland (EVC 163-04) on islands off Wilsons Promontory. Photo 2. Gippsland Plains Grassy Woodland (EVC 55-03) at Moormurng Flora and Fauna Reserve south-west of Bairnsdale. Photo 3. Wet Forest (EVC 30) in the Strzelecki ranges. Photo 4. Mangrove Shrubland (EVC 140) on the South Gippsland coastline at Corner Inlet. -

Appendix 3 Section 5A Assessments “Seven Part Tests”

APPENDIX 3 SECTION 5A ASSESSMENTS “SEVEN PART TESTS” Appendix 3: Seven Part Tests Swamp Sclerophyll Forest Swamp Sclerophyll Forest on Coastal Floodplains of the NSW North Coast, Sydney Basin and South East Corner bioregions is listed as an Endangered Ecological Community under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act (1995). It is not listed under the schedules of the Commonwealth Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999). Swamp Sclerophyll Forest on Coastal Floodplains of the NSW North Coast, Sydney Basin and South East Corner bioregions includes and replaces Sydney Coastal Estuary Swamp Forest in the Sydney Basin bioregion Endangered Ecological Community. This community is associated with humic clay loams and sandy loams, on waterlogged or periodically inundated alluvial flats and drainage lines associated with coastal floodplains (NSW Scientific Committee 2011). It occurs typically as open forests to woodlands, although partial clearing may have reduced the canopy to scattered trees or scrub. The understorey may contain areas of fernland and tall reedland or sedgeland which in turn may also form mosaics with other floodplain communities and often fringe wetlands with semi-permanent standing water (NSW Scientific Committee 2011). Swamp Sclerophyll Forest on Coastal Floodplains generally occurs below 20 metres ASL, often on small floodplains or where the larger floodplains adjoin lithic substrates or coastal sand plains (NSW Scientific Committee 2011). The species composition of Swamp Sclerophyll Forest is primarily determined by the frequency and duration of waterlogging and the texture, salinity nutrient and moisture content of the soil. The species composition of the trees varies considerably, but the most widespread and abundant dominant trees include Eucalyptus robusta Swamp Mahogany, Melaleuca quinquenervia and, south from Sydney, Eucalyptus botryoides Bangalay and Eucalyptus longifolia Woollybutt (OEH 2015a). -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

Ceratopetalum Gummiferum

Ceratopetalum gummiferum Family: Cunoniaceae Distribution: Open forest and rainforest of New South Wales, generally east of the Great Dividing Range. Common New South Wales Christmas bush Name: Derivation of Ceratopetalum....from Greek ceras, a horn and petalon, Name: a petal, referring to the petal shape of one species. gummiferum....producing a gum Conservation Not considered to be at risk in the wild. Status: General Description: Ceratopetalum is a small genus of 5 species, all occurring in Australia and New Guinea. C.gummiferum is the best known species and is widely cultivated both in Australia and overseas. The white flowers of Ceratopetalum gummiferum appear in October.... ....followed by the red sepals at around Christmas time. Photos: Brian Walters NSW Christmas bush is generally a large shrub or small tree which may reach 10 metres in its natural habit but is usually much smaller in cultivation where it rarely exceeds 5 metres. The foliage of the plant is very attractive. The leaves are up to 70mm long and are divided into three leaflets which are finely serrated. The new growth is often pink or bronze coloured. A mature NSW Christmas Bush in full display Photo: Brian Walters The main attraction of the plant is the massed display of the red sepals of the developing seed capsules which are commonly mistaken to be flowers. These are at their peak in early to mid summer, usually at Christmas in Australia. The true flowers are white in colour and are seen in late spring, although they are not particularly conspicuous. The sepals and foliage are widely used for cut flowers and the plant is farmed commercially for that purpose. -

Rare Or Threatened Vascular Plant Species of Wollemi National Park, Central Eastern New South Wales

Rare or threatened vascular plant species of Wollemi National Park, central eastern New South Wales. Stephen A.J. Bell Eastcoast Flora Survey PO Box 216 Kotara Fair, NSW 2289, AUSTRALIA Abstract: Wollemi National Park (c. 32o 20’– 33o 30’S, 150o– 151oE), approximately 100 km north-west of Sydney, conserves over 500 000 ha of the Triassic sandstone environments of the Central Coast and Tablelands of New South Wales, and occupies approximately 25% of the Sydney Basin biogeographical region. 94 taxa of conservation signiicance have been recorded and Wollemi is recognised as an important reservoir of rare and uncommon plant taxa, conserving more than 20% of all listed threatened species for the Central Coast, Central Tablelands and Central Western Slopes botanical divisions. For a land area occupying only 0.05% of these divisions, Wollemi is of paramount importance in regional conservation. Surveys within Wollemi National Park over the last decade have recorded several new populations of signiicant vascular plant species, including some sizeable range extensions. This paper summarises the current status of all rare or threatened taxa, describes habitat and associated species for many of these and proposes IUCN (2001) codes for all, as well as suggesting revisions to current conservation risk codes for some species. For Wollemi National Park 37 species are currently listed as Endangered (15 species) or Vulnerable (22 species) under the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995. An additional 50 species are currently listed as nationally rare under the Briggs and Leigh (1996) classiication, or have been suggested as such by various workers. Seven species are awaiting further taxonomic investigation, including Eucalyptus sp.