Exploring Criminal Justice in Saskatchewan* Rick Ruddell and Sarah Britto, University of Regina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Police Surveillance During the 1930S Michael Lonardo

Document generated on 09/30/2021 5:53 p.m. Labour/Le Travailleur Under a Watchful Eye: A Case Study of Police Surveillance During the 1930s Michael Lonardo Volume 35, 1995 Article abstract During the 1930s the Communist Party of Canada organized and promoted the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/llt35art01 working-class struggle against conditions resulting from the Depression. And while some have argued that the state's intelligence community paid little See table of contents attention to the efforts of the communists between the wars, the evidence reveals a major operation on the part of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to watch and suppress Communist Party activities. By tracing the involvement of Publisher(s) World War I veteran and Communist Party activist, Stewart O'Neil, in four radical movements — the Workers Ex-Servicemen's League, the On-to-Ottawa Canadian Committee on Labour History trek, the workers' theatre movement, and the Spanish Civil War— this paper demonstrates the extent of, and the tactics used by the RCMP in its surveillance ISSN and suppression of these radical movements. 0700-3862 (print) 1911-4842 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Lonardo, M. (1995). Under a Watchful Eye: A Case Study of Police Surveillance During the 1930s. Labour/Le Travailleur, 35, 11–42. All rights reserved © Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Review of Views from Fort Battleford: Constructed Visions of an Anglo-Canadian West by Walter Hildebrandt

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 1998 Review of Views from Fort Battleford: Constructed Visions of an Anglo-Canadian West By Walter Hildebrandt J.R. Miller University of Saskatchewan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Miller, J.R., "Review of Views from Fort Battleford: Constructed Visions of an Anglo-Canadian West By Walter Hildebrandt" (1998). Great Plains Quarterly. 2083. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2083 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BOOK REVIEWS 63 Saskatchewan originated in the unease he felt beginning work with the federal agenc:y in the 1970s at its tendency to diminish the role of aboriginal groups and valorize non-Native "pioneers," such as the mounted police, at the Fort Battleford historic site. Views from Fort Batt/eford provides a case study of the way in which public history, especially at historic sites, is contested terrain on which different groups vie to have their story told, or some times to have it dominate other narratives. Hildebrandt's account succeeds best when it traces-unfortunately not until its final sub stantive chapter-the history of historical in terpretation at Fort Battleford. This portion of the work lays bare the clash between metro politan interpretations of Canadian history that originated in central Canada and local sensibilities in the prairie west. -

Iacp New Members

44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 200 | Alexandria, VA 22314, USA | 703.836.6767 or 1.800.THEIACP | www.theIACP.org IACP NEW MEMBERS New member applications are published pursuant to the provisions of the IACP Constitution. If any active member in good standing objects to an applicant, written notice of the objection must be submitted to the Executive Director within 60 days of publication. The full membership listing can be found in the online member directory under the Participate tab of the IACP website. Associate members are indicated with an asterisk (*). All other listings are active members. Published July 1, 2021. Australia Australian Capital Territory Canberra *Sanders, Katrina, Chief Medical Officer, Australian Federal Police New South Wales Parramatta Walton, Mark S, Assistant Commissioner, New South Wales Police Force Victoria Melbourne *Harman, Brett, Inspector, Victoria Police Force Canada Alberta Edmonton *Cardinal, Jocelyn, Corporal Peer to Peer Coordinator, Royal Canadian Mounted Police *Formstone, Michelle, IT Manager/Business Technology Transformation, Edmonton Police Service *Hagen, Deanna, Constable, Royal Canadian Mounted Police *Seyler, Clair, Corporate Communications, Edmonton Police Service Lac La Biche *Young, Aaron, Law Enforcement Training Instructor, Lac La Biche Enforcement Services British Columbia Delta *Bentley, Steven, Constable, Delta Police Department Nelson Fisher, Donovan, Chief Constable, Nelson Police Department New Westminster *Wlodyka, Art, Constable, New Westminster Police Department Surrey *Cassidy, -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

RPS Annual Report 2009

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Regina Police Service 2009 Annual Report 1717 Osler Street | Regina, SK | reginapolice.ca Annual 2009 Report Chief’s Message Board of Police Commissioners The Regina Police Service has many things to be proud of from 2009. Success for The Regina Police Service has been achieved with our partners through community outreach and engagement. -

2006-2007 Annual Report

Government of Saskatchewan 2006-2007 Annual Report Saskatchewan Justice Saskatchewan Police Commission Table of Contents Letters of Transmittal .......................................................................................................................... 3 Saskatchewan Police Commission – Appointed Members ............................................................ 4 Role of the Commission .................................................................................................................... 5 Police Services .................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Cities, Towns and Villages Policed by Municipal Police (Actual Establishment).................... 6 Royal Canadian Mounted Police Extended Policing Contracts (Provincial) .................................... 7 Use of Firearms by Municipal Police ................................................................................................ 7 Use of Firearms by Royal Canadian Mounted Police (in Saskatchewan) ........................................ 7 Activities of the Commission ............................................................................................................ 8 Commission Budgets........................................................................................................................ 8 Meetings ......................................................................................................................................... -

Justice Responsesto Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls in Canada

A PARADIGMATIC SHIFT IN JUSTICE RESPONSESTO MISSING & MURDERED INDIGENOUS WOMEN & GIRLS IN CANADA RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE INAUGURAL JUSTICE PRACTITIONERS’ SUMMIT ON MISSING & MURDERED INDIGENOUS WOMEN & GIRLS IN CANADA JANUARY 7-8, 2016 • WINNIPEG, MB “ USTICE MUST ALWAYS JQUESTION ITSELF, JUST AS SOCIETY CAN EXIST ONLY BY MEANS OF THE WORK IT DOES ON ITSELF AND ON ITS INSTITUTIONS. — MICHEL FOUCAULT” (1983) REPORT INTRODUCTION In February 2015, families of Canada’s missing and murdered At length, the Summit’s breakout sessions, in each of the three Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) — alongside national identified areas of Victim Services, Policing and Prosecutions, Indigenous leadership; Premiers; and provincial, territorial developed a series of sector-specific MMIWG-themed and federal Ministers and/or their respective representatives — recommendations — all of which are contained within this report gathered in Ottawa for the inaugural National Roundtable on as calls to action to be delivered to the 2nd National Roundtable on MMIWG. MMIWG, which is scheduled to take place in Winnipeg, Manitoba on February 24-26, 2016. At, and from, this Roundtable, a commitment emerged from the Province of Manitoba to host the first-of-its-kind national Alongside these justice practitioners’ admonitions, this report summit meeting in respect of justice practitioners’ Best Practices includes critically imperative recommendations developed by in support of improved national information-sharing and judicial national MMIWG family members, which were derived -

Quorum National and International News Clippings & Press Releases 11

Quorum National and International News clippings & press releases Providing members with information on policing from across Canada & around the world 11 January 2013 Canadian Association of Police Boards 157 Gilmour Street, Suite 302 Ottawa, Ontario K2P 0N8 Tel: 613|235|2272 Fax: 613|235|2275 www.capb.ca BRITISH COLUMBIA ................................................................................................ 4 RCMP opens new $1B headquarters in Surrey, B.C. ........................................................................... 4 RCMP constable receives threat after deciding to run for office ..................................................... 4 Men with UN gang ties arrested after visit to Port Coquitlam shooting range .......................... 6 Editorial: Restoring faith in the RCMP ........................................................................................................... 7 Municipal police forces fold joint tactical team .......................................................................................... 9 ALBERTA ................................................................................................................ 10 Cash rewards may not often help, but also can't hurt, police say ................................................ 10 Council approves new approach to RCMP hiring ................................................................................. 12 How ‘Canada’s coolest’ Mountie is helping the RCMP’s reputation ........................................... 13 SASKATCHEWAN -

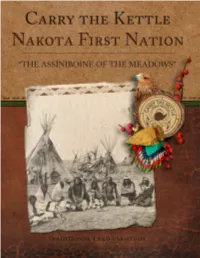

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early -

Miller Thomson LLP 1998-2008 WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS in CANADA

Robson Court MILLER 1000-840 Howe Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6Z 2M1 THOMSON LLP Tel. 604.687.2242 Barristers & Solicitors Fax. 604.643.1200 Patent & Trade-Mark Agents www.millerthomson.com VANCOUVER TORONTO CALGARY EDMONTON LONDON KITCHENER-WATERLOO GUELPH MARKHAM MONTRÉAL Wrongful Convictions in Canada Robin Bajer, Monique Trépanier, Elizabeth Campbell, Doug LePard, Nicola Mahaffy, Julie Robinson, Dwight Stewart International Conference of the International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law June 2007 This article is provided as an information service only and is not meant as legal advice. Readers are cautioned not to act on the information provided without seeking specific legal advice with respect to their unique circumstances. © Miller Thomson LLP 1998-2008 WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS IN CANADA Authors: Robin Bajer Monique Trépanier Elizabeth Campbell Doug LePard Nicola Mahaffy Julie Robinson Dwight Stewart TABLE OF CONTENTS WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS IN CANADA ...............................................................................2 CHAPTER ONE – Introduction and Background By Robin Bajer and Monique Trépanier..................................................................2 CHAPTER TWO – How Police Departments Can Reduce the Risk of Wrongful Convictions By Elizabeth Campbell and Doug LePard.............................................................12 CHAPTER THREE – Review: Wrongful Convictions and the Role of Crown Counsel By Nicola Mahaffy and Julie Robinson.................................................................40 -

Story Idea Als

Story Idea Krefeld, im Januar 2019 Historischer Familienspaß Geschichte zum Anfassen an Saskatchewans National Historic Sites Obwohl die Siedlungsgeschichte Kanadas für europäische Verhältnisse vergleichsweise jung ist, hat das Ahorn-Land viel Spannendes aus der Vergangenheit zu berichten! Verschiedene ausgewählte Bauwerke oder Naturdenkmäler, an denen sich einst signifikante Ereignisse zugetragen haben, zählen zu den kanadischen „National Historic Sites“. Sie illustrieren einige der entscheidendsten Momente in der Geschichte Kanadas. In den Sommermonaten lassen Mitarbeiter in zeitgenössischer Kleidung hier die Vergangenheit wieder aufleben. Mit bewegender Geschichte und spannenden Geschichten nehmen sie die Besucher auf eine interaktive Zeitreise mit. Auch in der Prärieprovinz Saskatchewan befinden sich einige dieser historischen Stätten, die Familienspaß für Jung und Alt versprechen. An der Batoche National Historic Site steht eine Zeitreise ins 19. Jahrhundert auf dem Programm. Am Ufer des South Saskatchewan River zwischen Saskatoon und Prince Albert gelegen, war Batoche nach seiner Gründung im Jahr 1872 eine der größten Siedlungen der Métis, d.h. der Nachfahren europäischer Pelzhändler und Frauen indigener Abstammung. Als sich die Métis gemeinsam mit lokalen Sippen vom Stamm der Cree und Assinoboine im Rahmen der Nordwest Rebellion gegen die kanadische Regierung auflehnten, war die Stadt im Jahr 1885 Schauplatz der entscheidenden Schlacht von Batoche. Noch heute sind an der Batoche National Historic Site die Einschlusslöcher der letzten Kämpfe zu sehen. Als Besucher kann man sich lebhaft vorstellen, wie sich die Widersacher seinerzeit auf beiden Seiten des Flusses in Vorbereitung auf den Kampf versammelten. Im Sommer locken hier verschiedene Events, wie beispielsweise das „Back To Batoche Festival“, das seit mehr als 50 Jahren jedes Jahr im Juli stattfindet und die Kultur und Musik der Métis zelebriert. -

Voices of Forensic Science

Chapter 14 The Harmful Repercussions of Wrongful Convictions Preetha Jayanthan, Bailey Hennessy "No one should ever be wrongfully deprived of their rights to liberty and freedom without just cause, yet in the past 25 years alone thousands of people have been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to tens of thousands of years in prison." (Kerik, B. B., 2015) Wrongful convictions occur when the criminal justice system fails to uphold its gold standards and thus miscarriages of justice occur. This chapter will take a close look into wrongful convictions caused by, improperly implementing the gold standards of forensic science through examining the aftermath of a wrongful conviction. By paying particular attention to the process of exonerating an individual; with an emphasis on the resources, or lack thereof, available. The chapter will then move towards the supposed ‘finish line’ of being exonerated. This decision, however, does not make up for the psychological trauma caused to the victim of a wrongful conviction. For many, an incorrect conviction can cost years, if not decades, of one’s life. This often causes wrongfully convicted individuals to lose friends, family, and other important relationships, ultimately resulting in mental health issues. What is a Wrongful Conviction? A wrongful conviction occurs when an individual is accused or sentenced for a crime they did not commit, in other words, a miscarriage of justice has occurred (Denov & Campbell, 2005). The root causes of wrongful convictions are seen to be both individual and systemic in nature (Denov & Campbell, 2005). Some examples 253 Are We There Yet? The Golden Standards of Forensic Science of root causes include false confessions, and bias in the system, such as tunnel vision (Denov & Campbell, 2005).