A COLLECTION of CREATIVE NONFICTION by Brandon Sneed November 2012 Director of Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning, July 22

SUNDAY MORNING, JULY 22 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (cc) Your Voice, Your Paid This Week With George Stepha- Paid Paid 2/KATU 2 2 Vote nopoulos (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) Paid Paid Wall Street Jour- Little Nikita ★★ (‘88) Sidney Poiti- 6/KOIN 6 6 nal Rpt. er, River Phoenix. ‘PG’ (1:38) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) 2012 Tour de France Stage 20. (Taped) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Curious George Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Black bears in Alaska. NOVA Time-traveling adventure. 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge (Part 2 of 3) (cc) (TVG) (Part 2 of 4) (cc) (TVG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Formula One Racing Grand Prix of Germany. (N Same-day Tape) (cc) Paid Paid 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Turning Point (cc) Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- Turning Point (cc) Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With From His Heart 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (TVPG) Hagin (TVG) (cc) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

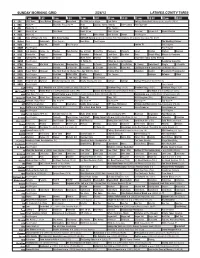

Sunday Morning Grid 2/26/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/26/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Rangers Horseland The Path to Las Vegas Epic Poker College Basketball Pittsburgh at Louisville. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Laureus Sports Awards Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Eye on L.A. Award Preview 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Daytona 500. From Daytona International Speedway, Fla. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program The Wedding Planner 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Thursday Morning, Aug. 2

THURSDAY MORNING, AUG. 2 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Kyra Sedgwick; Mario Live! With Kelly Joey Fatone; co- 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Cantone. (N) (cc) host Nick Lachey. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Reports from the Olympics. (N) (cc) XXX Summer Olympics Swimming, Beach Volleyball, Volleyball, Water Polo, Cycling, Rowing, Canoe- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) ing. (N Same-day Tape) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts Fire- Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Elmozilla. Growth Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) flies. (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) chart. (cc) (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A DJ’s 12/KPTV 12 12 death links to a fan. (TV14) Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid Jane and the Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Dragon (TVY) (TVY7) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Building a Differ- Lifestyle Maga- Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) ence (TVPG) zine James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury Tests solve paternity mys- The Steve Wilkos Show A man 32/KRCW 3 3 (TVPG) (TVPG) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass teries. -

The Merry Pranked, Along with Tripping on Tears Is His First Serious Foray Into Novel Writing

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM DAVID RUSK Tripping on Tears The Marquis Mark 1 2 Copyright © 2014 by David Rusk All rights reserved. The moral right of the author has been asserted. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents, other than those clearly in the public domain, either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the author, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Neither this book nor any portions of it may be reproduced in any form whatsoever without the prior permission in writing of the author. Cover design by Rhea Rusk 3 CONTENTS Also from David Rusk Title Page Copyright Dedication chapter ONE chapter TWO chapter THREE chapter FOUR chapter FIVE chapter SIX chapter SEVEN chapter EIGHT chapter NINE chapter TEN chapter ELEVEN chapter TVELVE chapter THIRTEEN chapter FOURTEEN chapter FIFTEEN chapter SIXTEEN chapter SEVENTEEN chapter EIGHTEEN chapter NINETEEN chapter TWENTY chapter TWENTY-ONE chapter TWENTY-TWO Excerpt from Tripping on Tears About the Author 4 To Rhea 5 chapter ONE “son-OF-a-bitch. Count Chocula. I used to love this shit.” Morgan Neil looked over to Sal Lunkin, a big, intimidating oaf of a man in his mid-fifties and one of his oldest associates. -

Commissioner: We Can Do Better Lee Grose ‘Any Thought That Current Federal Land Lewis County Leader Tells Management Practices Could

Toledo School Leaders Considering Bond to Renovate High School / Main 4 $1 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com A Bright Future for the Big Bird Fundraising to Rehabilitate the Yard Bird Is Nearly Complete / Main 7 Midweek Edition Thursday, Feb. 28, 2013 Centralia Police Arrest Two in Connection With Vandalism Spree / Main 3 Commissioner: We Can Do Better Lee Grose ‘Any Thought That Current Federal Land Lewis County Leader Tells Management Practices Could ... Support Congress to Treat Federal Forest Local Government or Land More Like Washington Universities Is Folly’ State Treats Its Own — Lewis County Commissioner Lee Grose, Testifying Before / Main 4 Congress This Week The Chronicle, file photo The wire of a high lead logging operation extends down a hillside in the Giford Pinchot National Forest 26 miles south of Randle in October 2011. Lewis County Commissioner Lee Grose testiied before Congress this week, saying logging in the Giford Pinchot and other national forests generates just $5 per thousand board feet, compared with $308 per thousand board feet on state-managed lands. “The U.S. Forest Service is woefully behind the state,” Grose, a Packwood Republican, told the U.S. House of Representatives. ToledoTel Pro Changes in Olympia and D.C. Could Make Rural Phone Rodeo Service More Expensive, Returning to Local Telecom Execs Say Lewis County? / Main 6 / Main 14 The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Weather On the Web Deaths Lewis County Area Since 1889 TONIGHT: Low 43 VIDEO: Perkins, William John, Follow Us on Twitter TOMORROW: High 57 Lewis County 89, Centralia @chronline Rain Likely Commissioner Wharton, Edward see details on page Main 2 Lee Grose “Eddie,” 84, Find Us on Facebook Testifies During Rochester www.facebook.com/ Weather picture by Garren Congressional Derango, Lisa A. -

Sunday Morning, Feb. 24

SUNDAY MORNING, FEB. 24 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Your Voice, Your NBA Countdown NBA Basketball Los Angeles Lakers at Dallas Mavericks. (N) (Live) 2/KATU 2 2 Vote (N) (Live) (cc) Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) Paid Bull Riding PBR Built Ford Tough College Basketball Cincinnati at 6/KOIN 6 6 Invitational. (Taped) (cc) Notre Dame. (N) (Live) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Golf Central Live PGA Tour Golf WGC Accenture 8/KGW 8 8 (N) (cc) Match Play Championship, Finals. Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature A Murder of Crows. Crows NOVA What motivates people to 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge are intelligent animals. (TVPG) kill. (cc) (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Fusion Evolution 2013 Daytona 500 (N) (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) (N) (cc) Paid Paid David Jeremiah Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- David Jeremiah Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With Time for Change 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (cc) Hagin (TVG) (cc) (TVG) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

The Last Stand

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 27, 2018 5:38:16 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of November 4 - 10, 2018 INSIDE The last •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 “The Last Ship” star stand Eric Dane •Hollywood Q&A Page14 In this final season of “The Last Ship,” Tom Chandler (Eric Dane, “Grey’s Anatomy”) and Bridget Regan (“Jane the Virgin”) face the newest menace to global stability: a Latin American insurgent group that threatens to invade the United States. The series follows the crew of the USS Nathan James, a navy destroyer saddled with the task of saving the world from a viral outbreak, and several ensuing global threats. The penultimate episode airs Sunday, Nov. 4, on TNT. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL To advertise here ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIESBay 4 Group Page Shell We Need: SALES & SERVICE please call Motorsports 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” (978) 946-2375 We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 27, 2018 5:38:17 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights CHANNEL Kingston Atkinson Sunday NESN Hockey NHL Vancouver Canucks NESN Hockey NHL Toronto Maple 9:55 p.m. -

Pdf, 394.06 KB

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Music Eighties-style synth-pop with strong drumbeat and staccato electric guitar plays in background of dialogue. 00:00:01 Adam Host Hey, it’s the hosts of Friendly Fire here, telling you to vote. And Pranica specifically, who to vote for. We’ve seen enough films on Friendly Fire to know what a “country descending into” type of genre gives you. We would very much like the story of these United States not to turn into that. 00:00:21 John Host Boy, you said it, Adam! Whether you consider yourself to be a real Roderick leftist who isn’t gonna vote for Biden ‘cause the Democrats and the Republicans are just two sides of the same coin, or whether you’re a red-blooded American Second Amendment fan who doesn’t wanna lose their freedoms and feels like they should vote for Donald Trump just to own the libs, we want to encourage you—as listeners of Friendly Fire—to join with us in voting for Joe Biden. The right-down-the-middle American candidate who isn’t going to drive our republic into civil war. 00:00:57 Ben Host And actually has a shot at winning! Harrison 00:01:00 John Host Yeah. Don’t for the Green Party here, please. And don’t vote for Trump. -

Emirates & Dubai

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the 12th consecutive year! Digital Widescreen April 2017 Embark on an epic journey with ROGUEa Star ONE Wars story © 2016 & TM Lucasfilm Ltd. Lucasfilm TM & 2016 © SHAHAB HOSSEINI TARANEH ALIDOOSTI WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY ASGHAR FARHADI PRODUCED BY ALEXANDRE MALLET-GUY AND ASGHAR FARHADI WITH BABAK KARIMI, FARID SAJJADIHOSSEINI AND MINA SADATI DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY HOSSEIN JAFARIAN CAMERAMAN PEYMAN SHADMANFAR EDITOR HAYEDEH SAFIYARI SOUND YADOLLAH NAJAFI, HOSSEIN BASHASH SOUND DESIGNER AND MIXER MOHAMMAD REZA DELPAK SOUND EDITOR REZA NARIMIZADEH A MEMENTO FILMS PRODUCTION AND ASGHAR FARHADI PRODUCTION PRODUCTION INCOPRODUCTION WITH ARTE FRANCE CINÉMA IN ASSOCIATION WITH MEMENTO FILMS DISTRIBUTION, ARTE FRANCE AND DOHA FILM INSTITUTEINTERNATIONAL SALES MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL | AND MORE © ABC Studios | BOX SETS | | NEW MUSIC | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD DRAMA | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT NEW MOVIES 15/03/2017 16:43 ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_54_APR17 44 200X250 OBCOFCApr17EX2.indd 51 EMIRATES 051_FRONT COVER_V2 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 528 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- THE LATEST MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning -

Senior Prom Tomorrow

SENIOR PROM TOMORROW No. 26 VOL. IX GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, P. C, MAY 3, 1928 GLEE CLUB GIVES GASTON-WHITE DEBATE SENIOR PROM TOMORROW NIGHT CLOSES POSTPONED. GEORGETOWN FORMAL SOCIAL FUNCTIONS THREE CONCERTS The annual Gaston-White Debate scheduled to take place in Gaston Hall Offerings Received With Great tonight has been postponed until next Social Career of Class Will Terminate With Affair Tomorrow and Enthusiasm at Woodstock— Thursday, May 10th. Teams repre- Saturday—Music is Furnished by Georgetown Collegians—Many Frank Shuman and Collegians senting the two junior debating so- Novel Features Promised by Committee—John K. Fitzgerald cieties at the Hilltop have been pre- Heads Committee in Charge. Please With Varied Renditions. paring for this occasion for over a month and a very interesting evening's The Glee Club has just completed a entertainment is expected. The sub- The Class of '28 will definitely relinquish the reins of social leadership to its suc- busy week, having made three different ject for the debate reads: "Resolved, cessor after its formal abdication tomorrow and Saturday. As the last notes of the appearances. The first of these was at That the present administration's Collegians orchestra come to an end, the social career of the Class of 1928 will belong the "G" Banquet held last Wednesday three-year naval program should be to history. As the guests depart, the Senior class of Georgetown will resign its night, where many numbers were sung adopted." throne to make place for the Class of 1929, and so on down the years. The formal to a very appreciative audience. -

Brasil 2014 Estadounidense Domingo 8, 20.30 Domingo 22, 22.00 :: Junio 2014 Por Fox Por Cinecanal

LOS SIMPSON: LINCOLN EPISODIO MUNDIAL LA VIDA DE UN HOMBRE CLAVE HOMERO SE CONVIERTE EN EN LA HISTORIA POLITICA ARBITRO DE BRASIL 2014 ESTADOUNIDENSE DOMINGO 8, 20.30 DOMINGO 22, 22.00 WWW.CABLEVISION.COM.UY :: JUNIO 2014 POR FOX POR CINECANAL VIVI EL MUNDIAL BRASIL 2014 INTERIOR EN CABLEVISION NOTA DE TAPA Viví el Mundial Brasil 2014 Para que nadie se pierda el máximo evento del fútbol mundial, Cablevisión emitirá los 64 partidos en vivo, con la mejor calidad de imagen. El Mundial 2014 será un evento único para los uruguayos, que no perdemos la fe a pesar de estar en el grupo más difícil del Torneo, junto a dos campeones mundiales y Costa Rica. Es que muchos pensamos que fuera cual fuera el grupo, para Uruguay nunca es sencillo y que cuando el oponente es fuerte, jugamos mejor. Por otra parte, confiamos en jugadores que han sido muy importan- tes en las mejores ligas de Europa, destacándose Luis Suarez, goleador y elegido mejor jugador de la Liga Premier de Inglaterra. En cada hogar, en cada lugar de trabajo y reunión de amigos esta- rá el televisor encendido, con Cablevisión llevando las imágenes de un nuevo Campeonato Mundial, con los 64 partidos en vivo y en directo, en calidad digital o HD, para que nadie se pierda la mayor fiesta deportiva del mundo. ESTRENOS CINE Invasión del mundo Los Pitufos 2 (Battle L.A.) ACCIÓN HHH (The Smurfs 2) INFANTIL HHH Miércoles 4, 22.00 por Universal | Repite domingo 15, 22.10 Sábado 7, 22.00 por HBO | Repite miércoles 11, 22.00 CON Aaron Eckhart, Michael Peña y Michelle Rodriguez CON Hank Azaria, Neil Patrick Harris y Brendan Gleeson La invasión extraterrestre se convierte en una realidad. -

New Proposal Threatens Eminent Domain Authority

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COUNTIES n WASHINGTON, D.C. VOL. 44, NO. 2 n January 30, 2012 ‘Super Wi-Fi’ Four Florida comes to counties plan New Hanover for climate County, N.C. change impacts By Charles Taylor By Charles Taylor SENIOR STAFF WRITER SENIOR STAFF WRITER New Hanover County, N.C. Monroe County again finds itself on the leading — more water than edge of technology as the first local CONTENT land — is the “canary government in the U.S. to launch a in the coal mine” “super Wi-Fi” network. for the effects of climate change The way was paved three years in southern Florida, according ago, when the county led the nation to County Administrator Roman in the switch from analog to digital Gastesi. TV, making available unlicensed Over the past century, the sea “white space” — unused frequencies level has risen 9 inches at Key West, the county seat. And of Monroe See WI-FI page 6 County’s 3,700 square miles, about 2,700 square miles are water. QuickTakes “We are totally vulnerable,” Photo courtesy of Bill and Bob Gibson Gastesi said. “We can’t just move States with the Best (l-r) Bill and Bob Gibson are “mirror-image” identical twins — one’s right-handed, the other a leftie. Both inland; there’s very little inland to Public Schools took their seats this month as new members of the Board of Supervisors in their respective southwest move into.” Virginia counties. To learn more about their similarities, see story on page 4. (Based on six areas of educational So a recently released draft policy and performance) Regional Climate Change Action Plan is important to Monroe, and 1 – Maryland to its partners in the Southeast 2 – Massachusetts Florida Regional Climate Change 3 – New York New proposal threatens Compact: Miami-Dade, Broward 4 – Virginia and Palm Beach counties.