Paying Judges: Why, Who, Whom, How Much?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSG in Africa - 2.1 FIVE KEY ACTORS

SSG in Africa - 2.1 FIVE KEY ACTORS http://www.ssronline.org/ssg_a/index4.cfm?id=16&p=16 framework for governance in the security sector. Whilst noting that the authors of this Handbook are careful not to describe it as the road-map or Guidebook for security sector governance in Africa, they have examined the scope, processes, actors and contexts of security sector reform in Africa, and reflected the diversities of terrains and directions to produce, what is to my knowledge the first comprehensive and practical guide on governing the security sector, drawing on both good and bad practices, providing realistic entry-points for broadening the security agenda in our states and at the same time suggesting ways of ensuring the professionalisation of our security forces in defence of the states and protection of the citizens. As we continue our own task in he building of a comprehensive security architecture, we will utilise this Handbook extensively in that work. It is my hope the practical tools and lessons presented here from a variety of experiences will inspire, support and assist our security institutions, military academies, research institutions, civil society organisations and international actors in the critical task of security sector governance in Africa Professor Alpha Oumar Konare Chairperson, African Union Commission. Acknowledgements The handbook has been produced by a collaborative effort among researchers and practitioners across Africa. Core members of the writing team are: Nicole Ball, 'J. Kayode Fayemi, 'Funmi Olonisakin, and Rocklyn Williams. Contributors to the handbook are: Len LeRoux, Ntsiki Motumi, Janine Rausch, and Mark Shaw. The handbook has also been the subject of consultations during regional meetings held by affiliated research networks in Western and Southern Africa during which researchers, policy makers, and practitioners gave generously of their time. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 48331-TH INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM DOCUMENT Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A PROPOSED PUBLIC SECTOR REFORM DEVELOPMENT POLICY LOAN (PSRDPL) IN THE AMOUNT OF US$1BILLION TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized KINGDOM OF THAILAND OCTOBER 21, 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit East Asia and Pacific Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR October 1 – September 30 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as at October 2010) Currency Unit Thai Baht (THB) US$1.00 29.89 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank NESDB National Economic and Social Development Board BOB Bureau of the Budget OAG Office of the Auditor General’s BOP Balance of Payments OCSC Office of the Civil Service Commission BOT Bank of Thailand OPDC Office of the Public Sector Development Commission CDP Country Development Partnership PAD People’s Alliance for Democracy CDP-G Country Development Partnership with PAMP Public Administration Management Plan Thailand on Governance and Public Sector Reform CGD Comptroller General’s Department PART Performance Assessment Rating Tool COA Chart of Accounts PDMO Public Debt Management Office DPL Development Policy Loan PEFA Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability DSA Debt -

The Record Producer As Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry

The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael John Gilmour Howlett April 2009 ii I certify that the work presented in this dissertation is my own, and has not been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University: _____________________________________________________________ Michael Howlett iii The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry Abstract What is a record producer? There is a degree of mystery and uncertainty about just what goes on behind the studio door. Some producers are seen as Svengali- like figures manipulating artists into mass consumer product. Producers are sometimes seen as mere technicians whose job is simply to set up a few microphones and press the record button. Close examination of the recording process will show how far this is from a complete picture. Artists are special—they come with an inspiration, and a talent, but also with a variety of complications, and in many ways a recording studio can seem the least likely place for creative expression and for an affective performance to happen. The task of the record producer is to engage with these artists and their songs and turn these potentials into form through the technology of the recording studio. The purpose of the exercise is to disseminate this fixed form to an imagined audience—generally in the hope that this audience will prove to be real. -

World Bank Document

Report No. 23349-MK FYR of Macedonia Public Expenditure and Institutional Review Public Disclosure Authorized April 2, 2002 Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized u Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank CURRENCY AND EQUI'VALENTS Currency Unit USUS$ 1 = Denar 67 FISCAL YEAR January 1-December 31 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS BOO Build-operate-own BRA Bank Rehabilitation Agency CBA Collective Bargaining Agreements CEEC Central and Eastern European countries CPI Consumer Price Index FDI Foreign direct investment FIAS Foreign Investment Advisory Service FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) FTA Free Trade Agreement FWA Framework Agreement GoM Government of the FYR Macedonia GNFS Goods and non-factor services HIs Health Institutions HIF Health Insurance Fund IAS International Accounting Standards MIPA Macedonia Investment Promotion Agreement MUCE Ministry of Urban Planning, Construction and the Environment NBRM National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia PEIR Public Expenditure & Institutional Review PA Privatization agency PTA Preferential trade agreement ROW Rest of the world PRO Public Revenue Office RER Real exchange rate SB Stopanska Bank DIF Deposit Insurance Fund SEC Securities and Exchange Commission SRP Special Restructuring Program SSO State and socially owned enterprises VAT Value added tax ZPP Zaved za Platen Promet (payment bureau) Vice President: Johannes F. Linn Country Director: Christiaan J. Poortman Sector Director: Pradeep K. Mitra Sector Leader: Helga W. Muller Task Manager: Pascale N. Kervyn de Lettenhove ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Public Expenditure and Institutional Review (PEIR) has been prepared for the Government of FYR Macedonia. A World Bank team, working with Government officials and other donors, including the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom's Department for International Development (DFID), completed the first draft for discussion with the Government in 2000. -

KNOW YODI. COLLEGE ¦ Was Perfectly Justified

. Inter-fraternity President Editorial Glee Club Pres ents Harry Paul Is asks the freshman Delegation Goes To Augusta ' and non fraternity upper-class- A settlement effected yesterday between the owner of the ^ Where Meeting Wi th Acheson Messiah Saturda y -' men to forestall forming opin- •* Elmwood Hotel and a student faculty committee of Colby College ions about fraternities until closed the incident of discrimination which occured last Saturday Results In Terminatin g Affair their knowledge -of fraternal evening at the aforementioned establishment; In a public re- The first post-war production of rules arid regulations, is suffi- lease the owner of the hotel stated that it "is not the policy of the On Saturday evening, December 7, Handel's "Messiah" , at Colby will be cient to arrive at fair and intelli- hotel to practice discrimination and admitted that the in- William Mason a Colby College stu- presented Saturday evening, Decem- gent conclusions. By the time ' cident in question was . a case of discrimination due to exer- dent, was refused service' in the Pine ber 14 iri the Women's Union • with a the Echo goes to press the In- cise of bad judgment. Tree Tavern. Upon speaking to the chorus; of two'hundred and fifty-Col- ter-fraternity counsel ' will have . This declaration has been accepted "by the college and the Manager of the Elmwood, Henry Mc- by and 1 Bowdoin students,-townspeo- " distributed copies of these -rules "Elmwood Incident" is now closed. However, despite the fa'ct Avoy, Mason was informed that he ple and faculty, supported by a string ' around -the campus. -

2 to Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different

2 To Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different The context for difference This chapter aims to identify some of the bands that enjoyed chart success during the late 1970s and ’80s and identify their artistic traits by means of conversations with band members and those close to the bands. This chapter does not claim to be a definitive account or an inclusive list of innovative bands but merely a viewpoint from some of the individuals who were present at the time and involved in music, creativity and youth culture. Some of these individuals were in the eye of the storm while others were more on the periphery. However, common themes emerge and testify to the Scouse resilience identified in the previous chapter. Also, identifying objective truth is a difficult task, as one band member will often have a view of his band’s history that conflicts with that of other members of the same band. As such, it is acknowledged that this chapter presents only selective viewpoints. Trying something new: In what ways were the Liverpool bands creative and different? ‘Liverpool has always made me brave, choice-wise. It was never a city that criticized anyone for taking a chance.’ David Morrissey1 In terms of creativity, the theory underpinning this book which was stated in Chapter 1 is that successful Liverpool bands in the 1980s were different from each other and did not attempt to follow the latest local or national pop music trends. None of the bands interviewed falls into the categories of punk, disco or New Romantic, which were popular trends at the time. -

THE ACICA REVIEW December 2015 | Vol 3 | No 2 | ISSN 1837 8994

The ACICA Review – December 2015 1 er 2013 6 THE ACICA REVIEW December 2015 | Vol 3 | No 2 | ISSN 1837 8994 2 The ACICA Review – December 2015 CONTENTS The ACICA Review December 2015 INFORMATION PAGE President’s Welcome ……………………………………………………………….…….………….......... 3 Secretary General’s Report………………………………………………………………..…………..…... 4 The Amazing World of Arbitration: Australian Perspectives …………………………………………… 9 AMTAC Chair’s Report …………………………………………………………………….…………….… 10 News in Brief ………………………………………………………………………………….………..…… 12 CASE NOTES John Holland Pty Ltd v Kellogg Brown & Root Pty Ltd (No 2) [2015] NSWSC 565……………..…... 13 All's Fair in Love and Award Enforcement: Yukos V Russian Federation………………………..…... 15 Respecting party autonomy and resisting domesticity in international arbitration……………………. 19 OTHER ARTICLES Aircraft Support Industries ………………………………………………………………………………… 22 ISDS in ChAFTA – where’s the beef?……………………..….……………………………………...…… 25 The Third APEC Senior Officials’ Meeting ………………………………………………………….……. 29 Getting to Yes Sooner – some footnotes from the trenches ..…………………………………………. 30 The TPP Investment Chapter: Mostly More of the Same …………………………………………….… 32 Commercial Courts: An alternative mechanism for the settlement of international commercial disputes ……………………………………………………………………………..….……... 35 The International Arbitration Act 1974 – summarising recent legislative amendments ……….……. 39 2015 New South Wales Young Lawyers International Arbitration Moot …………………………..…. 41 The 3rd Annual International Arbitration Conference in Sydney -

Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark Mp3, Flac, Wma

Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark Country: UK Released: 1980 Style: Electro, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1692 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1304 mb WMA version RAR size: 1211 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 621 Other Formats: MP2 ASF AUD XM MIDI MOD AA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Bunker Soldiers 2:54 2 Almost 3:44 Mystereality 3 2:45 Saxophone – Martin Cooper 4 Electricity 3:39 5 The Messerschmitt Twins 5:41 Messages 6 4:12 Guitar – Dave Fairbairn Julia's Song 7 4:41 Guitar – Dave FairbairnLyrics By – Julia KnealePercussion – Malcolm Holmes 8 Red Frame/White Light 3:12 9 Dancing 2:59 10 Pretending To See The Future 3:46 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin – DICD 2 Copyright (c) – Virgin Records Ltd. Recorded At – The Gramophone Suite Mixed At – The Gramophone Suite Glass Mastered At – DADC Austria Credits Engineer – Paul Collister Photography By [Foto] – Trevor Key Producer – Chester Valentino, Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark Voice, Bass, Keyboards, Percussion [Electronic], Drum Programming – Andy McCluskey Voice, Keyboards, Percussion [Electronic & Acoustic], Drum Programming – Paul Humphreys Written-By, Arranged By, Performer – Andy McCluskey, Paul Humphreys Notes Recorded and mixed at The Gramophone Suite, Liverpool. ℗ 1980 Dindisc Ltd./© Virgin Records Ltd. Manufactured in Austria "Mastered by DADC Austria" credit on matrix. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 7777860172 2 SPARS Code: AAD -

13 Insights from the Development Sector

13 Insights from the Development Sector Paul M. Bisca and Gary J. Milante evelopment is big. It encompasses economic growth, but also social development through civil society, state-building (improving the capacity of the state to deliver Dservices), and political institutions, including rule of law.1 New Institutional Economics (NIE) has changed how development practitioners think about growth and development over the past 15 years.2 NIE has shown that “how” people manage their relations through formal and informal institutions affects the efficiency and distribution of service delivery and the provision of public goods. This chapter is written by development practitioners who work at the intersection of development and defense, and it is written from the perspective that institutions, including defense institutions, are vital means through which societies coordinate their social, political, and economic activity. The authors have seen places where this institutional reform has created real transformation that led to previously inconceivable peace, prosperity, and growth. More often, unfortunately, tragedies occurred where policymakers ignored institution building, or undertook it as purely a technocratic exercise with no appreciation of the underlying politics. The result was dismal failure. Consequently, the development community has much to learn about how to adapt local solutions, informed by these successes and the failures, as do those working on defense institution building (DIB). The first section of this chapter introduces key concepts in NIE to the non-economist, including a definition of institutions and the relationship between institutions, public goods, and political economy. Next, it identifies four common mistakes or pitfalls seen in development practice: missing ownership, isomorphic mimicry, perplexing complexity, and unrealistic timeframes. -

Issue 142.Pmd

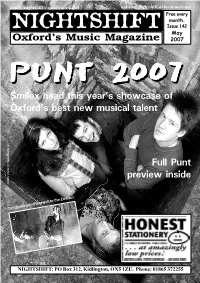

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 142 May Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 PUNTPUNTPUNTPUNTPUNTPUNT 200720072007200720072007 Smilex head this year’s showcase of Oxford’s best new musical talent Full Punt preview inside Smilex photo by Sam Shepherd Candyskins bid farewell to the Zodiac! NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] singers to submit application forms to perform. Artists must complete an online form at www.thisistruck.com, providing a MySpace link where possible – they will not be accepting demos. All acts must be from Oxfordshire and the Truck committee is particularly keen to hear from younger bands. Truck 10 takes place at Hill Farm, Steventon, over the weekend of the 21st and 22nd July. TICKETS FOR CORNBURY FESTIVAL are THE CANDYSKINS, THE NUBILES, selling faster than in previous years and the OMD play at the New Theatre on Saturday rd DUSTBALL AND THE DAISIES are all set to event again looks like selling out. Headline acts 23 June as part of a national Greatest Hits reform to bid farewell to the Zodiac this month. for the festival, which takes place at Cornbury tour. The original line-up of the band, Paul The Zodiac closes its doors for the last time on Park near Charlbury, are David Gray and Humphreys, Andy McLusky, Malcolm Holmes Thursday 17th May before undergoing a Blondie who are joined by The Waterboys, The and Martin Cooper, reformed last year and £2,000,000 refurbishment, which will see it re- Feeling and The Proclaimers, who returned to recently played a series of dates celebrating open at the end of September as the Oxford the top of the singles charts last month. -

September 23, 1991

James Madison University MONDAY SEPTEMBER 23,1991 VOL 69, NO. 9 Faculty still face time crunch interview in October 1990. by Kknberty Brothers, Twelve hours is considered a full- A recent survey conducted by the Faculty Senate of Virginia addressed Julie Provenson time load for a student. the satisfaction and morale of teachers with respect to certain aspects of their jobs. Here are the responses to two of the questions... & John Parmdee JMU professors are "all running, investigative team writers screaming and always behind. And the 1) The mix of teaching, research, administration, and service Two years of budget cuts in administration sort of floats above it (as applicable) that gjk J> Virginia's higher education system has all," said Dr. Catherine Boyd, JMU I am required to do: *&$* ,V^ j^ y2s* put a strain on JMU's faculty, leaving professor of history. them with heavy teaching workloads, "I love teaching history, but how larger classes, and a feeling of much do you love doing what you're frustration. put through the grinder for?" Virginia faculty reported working an average of 52 hours a week in the 1991 Virginia Faculty Survey, which was 2) Research assistance that I receive: released by the State Council for Higher Education in Virginia in June. «< ^ Forty-one percent of faculty at comprehensive institutions expect an increase in teaching hours. mm 37.5 21.9 37.5 First in a series "I think teaching loads are heavy," Other said JMU President Ronald Carrier. schools 29.9 27.3 30.4 "But there are some reduced teaching And with the future of the budget loads. -

Governing Failure - Provisional Expertise and the Transformation of Global Development Finance

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Best, Jacqueline Book — Published Version Governing Failure - Provisional Expertise and the Transformation of Global Development Finance Provided in Cooperation with: Cambridge University Press (CUP) Suggested Citation: Best, Jacqueline (2014) : Governing Failure - Provisional Expertise and the Transformation of Global Development Finance, ISBN 978-1-139-54273-9, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139542739 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/181396 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/ www.econstor.eu Governing Failure Jacqueline Best argues that the changes in International Monetary Fund, World Bank and donor policies in the 1990s, towards what some have called the ‘Post-Washington Consensus,’ were driven by an ero- sion of expert authority and an increasing preoccupation with policy failure.