Museum of Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mioceno Tardío) De Entre Ríos, Argentina

Rev. bras. paleontol. 18(3):521-546, Setembro/Dezembro 2015 © 2015 by the Sociedade Brasileira de Paleontologia doi: 10.4072/rbp.2015.3.14 ACTUALIZACIÓN SISTEMÁTICA Y FILOGENIA DE LOS PROTEROTHERIIDAE (MAMMALIA, LITOPTERNA) DEL “MESOPOTAMIENSE” (MIOCENO TARDÍO) DE ENTRE RÍOS, ARGENTINA GABRIELA INÉS SCHMIDT Laboratorio de Paleontología de Vertebrados, Centro de Investigaciones Científi cas y Transferencia de Tecnología a la Producción (CICYTTP-CONICET), Materi y España (E3105BWA), Diamante, Entre Ríos, Argentina. [email protected] ABSTRACT – SYSTEMATIC UPDATE AND PHYLOGENY OF THE PROTEROTHERIIDAE (MAMMALIA, LITOPTERNA) FROM THE “MESOPOTAMIENSE” (LATE MIOCENE) OF ENTRE RÍOS PROVINCE, ARGENTINA. A systematic update of the species of Proterotheriidae (Litopterna) from the “Mesopotamiense” of Entre Ríos Province (Argentina) is performed, and their phylogenetic relationships with other members of the family are tested. Brachytherium cuspidatum Ameghino is validated (considered nomen dubium hitherto) and a sexual dimorphism is proposed for this species. This idea is based on metric, but not morphological, differences among the specimens included in it, which is supported by a discriminant analysis. Neobrachytherium ameghinoi Soria and Proterotherium cervioides Ameghino are also valid, and Epitherium? eversus (Ameghino) is assigned to the genus Diadiaphorus. Detailed descriptions of the specimens are presented for each taxon, and their diagnosis are revised. Key words: Proterotheriidae, Ituzaingó Formation, Entre Ríos Province, systematics, phylogeny. RESUMO – Uma atualização sistemática, das espécies de Proterotheriidae (Litopterna) presentes no “Mesopotamiense” da Província de Entre Ríos, Argentina, é realizada, bem como são testadas as suas relações fi logenéticas com outros integrantes da família. Brachytherium cuspidatum (previamente considerada nomen dubium) é revalidada, e um dimorfi smo sexual é proposto para esta espécie. -

Evolutionary and Functional Implications of Incisor Enamel Microstructure Diversity in Notoungulata (Placentalia, Mammalia)

Journal of Mammalian Evolution https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-019-09462-z ORIGINAL PAPER Evolutionary and Functional Implications of Incisor Enamel Microstructure Diversity in Notoungulata (Placentalia, Mammalia) Andréa Filippo1 & Daniela C. Kalthoff2 & Guillaume Billet1 & Helder Gomes Rodrigues1,3,4 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Notoungulates are an extinct clade of South American mammals, comprising a large diversity of body sizes and skeletal morphologies, and including taxa with highly specialized dentitions. The evolutionary history of notoungulates is characterized by numerous dental convergences, such as continuous growth of both molars and incisors, which repeatedly occurred in late- diverging families to counter the effects of abrasion. The main goal of this study is to determine if the acquisition of high-crowned incisors in different notoungulate families was accompanied by significant and repeated changes in their enamel microstructure. More generally, it aims at identifying evolutionary patterns of incisor enamel microstructure in notoungulates. Fifty-eight samples of incisors encompassing 21 genera of notoungulates were sectioned to study the enamel microstructure using a scanning electron microscope. We showed that most Eocene taxa were characterized by an incisor schmelzmuster involving only radial enamel. Interestingly, derived schmelzmusters involving the presence of Hunter-Schreger bands (HSB) and of modified radial enamel occurred in all four late-diverging families, mostly in parallel with morphological specializations, such as crown height increase. Despite a high degree of homoplasy, some characters detected at different levels of enamel complexity (e.g., labial versus lingual sides, upper versus lower incisors) might also be useful for phylogenetic reconstructions. Comparisons with perissodactyls showed that notoungulates paralleled equids in some aspects related to abrasion resistance, in having evolved transverse to oblique HSB combined with modified radial enamel and high-crowned incisors. -

Dc Nº 360-2018.Pdf

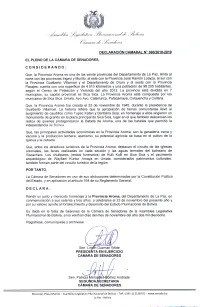

. ,T, • ,-:;:/f; I/ .17' ?I' //1/{-11/..1/Ir• // 4/ (;;-,71/ ,./V /1://"Ve DECLARACIÓN CAMARAL N° 360/2018-2019 EL PLENO DE LA CÁMARA DE SENADORES, CONSIDERANDO: Que, la Provincia Aroma es una de las veinte provincias del Departamento de La Paz, limita al norte con las provincias Ingavi y Murillo, al este con la Provincia José Ramón Loayza, al sur con la Provincia Gualberto Villarroel y el Departamento de Oruro y al oeste con la Provincia Pacajes; cuenta con una superficie de 4.510 kilómetros y una población de 98.205 habitantes, según el Censo de Población y Vivienda del año 2012. La provincia está dividida en 7 municipios, su capital provincial es Sica Sica. La Provincia Aroma está compuesta por los municipios de Sica Sica, Umala, Ayo Ayo, Calamarca, Patacamaya, Colquencha y Collana. Que, la Provincia Aroma fue creada el 23 de noviembre de 1945, durante la presidencia de Gualberto Villarroel. La historia refiere que la apropiación de tierras comunitarias llevó al surgimiento de caudillos como Tupac Katari y Bartolina Sisa, en homenaje a ellos erigieron un monumento de granito en la plaza principal de Sica Sica, lugar en el que también descansan los restos de quienes protagonizaron la Batalla de Aroma, una de las batallas que permitió la independencia de Bolivia. Que, las principales actividades económicas en la Provincia Aroma, son la ganadería ovina y vacuna y la producción lechera; asimismo, su potencial agrícola se basa en el cultivo de la quinua y la cebada. Que, entre los atractivos turísticos de la Provincia Aroma, destacan el circuito de las iglesias coloniales, las ferias realizadas en cada sección y las aguas termales del balneario de Viscachani. -

“Toscas Del Río De La Plata” (Buenos Aires, Argentina)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by El Servicio de Difusión de la Creación Intelectual Soibelzon et al.: Análisis faunístico de vertebrados deRev. las Mus. toscas Argentino del Río de Cienc. La Plata Nat., n.s.291 10(2): 291-308, 2008 Buenos Aires, ISSN 1514-5158 Análisis faunístico de vertebrados de las toscas del Río de La Plata (Buenos Aires, Argentina): un yacimiento paleontológico en desaparición E. SOIBELZON1, G. M. GASPARINI1, A. E. ZURITA2 & L. H. SOIBELZON1 1Departamento Científico de Paleontología de Vertebrados, Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, UNLP. Paseo del Bosque s/n, 1900 La Plata. Argentina. CONICET. [email protected]. 2 Centro de Ecología Aplicada del Litoral (CECOAL-CONICET) y Universidad Nacional del Nordeste, Corrientes, Argentina Abstract: Faunistic analisys of vertebrates from las toscas del Río de La Plata (Buenos Aires, Argentina): a palaeontological site in disappearance. At the coast of the río de la Plata in the Buenos Aires city lies a classic paleontological site, known as toscas del Río de La Plata or simple as las toscas. It has been studied for over 120 years and, although it has been widely spread, today is only possible to observe it during low tide. For this reason, most of the available materials are those collected during the first half of the XXth century, and that so far have only been incorporated into scarce taxonomic reviews. Among the fossils collected in las toscas highlights Glyptodon munizi Ameghino, Neosclerocalyptus pseudornatus Ameghino, Mesotherium cristatum Serrés, Arctotherium angustidens Gervais y Ameghino and Theriodictis platensis (Mercerat); all are exclusive species from the Ensenadan Stage (early to -middle Pleistocene). -

La Paz Beni Cochabamba Oruro Pando Pando Lago La Paz Potosi

70°0'0"W 69°0'0"W 68°0'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°0'0"W S S " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 2 Roads (Caminos) Franz Tamayo Manco Kapac 2 1 1 Rivers (Rios) General Jose Manuel Murillo Pando Pando Places (Lugares) Gualberto Villarroel Mu¤ecas PROVINCIA Ingavi Nor Yungas Abel Iturralde Inquisivi Omasuyos Aroma Larecaja Pacajes Bautista Saavedra Loayza Sur Yungas Camacho Los Andes Caranavi S S " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 3 Ixiamas 3 1 1 YACUMA S S " " 0 BALLIVIANREYES 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 4 4 1 GENERALBALLIVIAN Beni 1 San Buenaventura FRANZTOMAYOCAUPOLICAN Apolo Pelechuco S S " " 0 0 ' Curva ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 1 Gral.Perez (Charazani) 1 La Paz Ayata Mocomoco Tacacoma Guanay Palos Blancos Puerto Acosta Aucapata LAPAZ Chuma CAMACHO Quiabaya Tipuani Pto.CarabucoChaguaya Sorata Caranavi Ancoraimes S S " " 0 NORDYUNGASNORYUNGAS 0 ' Lago La Paz ' 0 0 ° ° 6 MANCOKAPAC Achacachi 6 1 La Asunta 1 Copacabana Coroico Batallas La Paz Coripata San Pedro de Tiquina MURILLO Pto. Perez Pucarani Chulumani El Alto Yanacachi SURYUNGA AYOPAYA Tiahuanacu Laja Irupana Inquisivi Desaguadero Guaqui Achocalla Cajuata Mecapaca Palca INGAVI Viacha Licoma Collana Calamarca CairomaQuime S S " Nazacara de Pacajes " 0 INQUISIVI 0 ' Comanche Sapahaqui ' 0 Malla 0 ° ° 7 Colquencha 7 1 Caquiaviri Ayo-Ayo Luribay Cochabamba 1 Santiago de Machaca Coro Coro Patacamaya Ichoca Catacora Yaco CERCADO Santiago de Callapa Sica-Sica(V.Aroma) PACAJESCalacoto Umala Colquiri TAPACARI PUNATA Chacarilla QUILLACOLLO S.Pedro de Curahuara ARCEARZE Papel Pampa ARQUE Chara?a TARATA BARRON Oruro CAPINOTA CERCADO Potosi 70°0'0"W 69°0'0"W 68°0'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°0'0"W Created: 02-FEB-2008/11:30 Projection/Datum: WGS84 Map Doc Num: ma017_bol_laPazMunicipal_A4_v1 GLIDE Num: FL-2007-000231-BOL Reference Map of La Paz Depar tment, Bolivia 0 20 40 80 120 160 MapAction is grateful for the support km The depiction and use of boundaries, names and associated data shown here of the Vodafone Group Foundation do not imply endorsement or acceptance by MapAction. -

Michael O. Woodburne1,* Alberto L. Cione2,**, and Eduardo P. Tonni2,***

Woodburne, M.O.; Cione, A.L.; and Tonni, E.P., 2006, Central American provincialism and the 73 Great American Biotic Interchange, in Carranza-Castañeda, Óscar, and Lindsay, E.H., eds., Ad- vances in late Tertiary vertebrate paleontology in Mexico and the Great American Biotic In- terchange: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología and Centro de Geociencias, Publicación Especial 4, p. 73–101. CENTRAL AMERICAN PROVINCIALISM AND THE GREAT AMERICAN BIOTIC INTERCHANGE Michael O. Woodburne1,* Alberto L. Cione2,**, and Eduardo P. Tonni2,*** ABSTRACT The age and phyletic context of mammals that dispersed between North and South America during the past 9 m.y. is summarized. The presence of a Central American province of cladogenesis and faunal differentiation is explored. One apparent aspect of such a province is to delay dispersals of some taxa northward from Mexico into the continental United States, largely during the Blancan. Examples are recognized among the various xenar- thrans, and cervid artiodactyls. Whereas the concept of a Central American province has been mentioned in past investigations it is upgraded here. Paratoceras (protoceratid artio- dactyl) and rhynchotheriine proboscideans provide perhaps the most compelling examples of Central American cladogenesis (late Arikareean to early Barstovian and Hemphillian to Rancholabrean, respectively), but this category includes Hemphillian sigmodontine rodents, and perhaps a variety of carnivores and ungulates from Honduras in the medial Miocene, as well as peccaries and equids from Mexico. For South America, Mexican canids and hy- drochoerid rodents may have had an earlier development in Mexico. Remarkably, the first South American immigrants to Mexico (after the Miocene heralds; the xenarthrans Plaina and Glossotherium) apparently dispersed northward at the same time as the first Holarctic taxa dispersed to South America (sigmodontine rodents and the tayassuid artiodactyls). -

LCFPD Track Identification and Walking Gaits

Track Identification Cat Rabbit ➢ 4 toes on each foot ➢ 4 toes on each foot ➢ round tracks ➢ oval tracks ➢ no claw marks ➢ front of skid has claw marks ➢ hind paws narrower ➢ almost impossible to see pads Dog, Fox, Coyote Raccoon ( Dog family) ➢ 5 toes on each foot ➢ 4 toes on each foot ➢ toes close together ➢ tracks maple leaf shaped or egg shaped ➢ toes long and finger shaped ➢ claw marks appear ➢ claw marks appear ➢ front feet larger Weasel, Skunk, Mink Opossum (Weasel Family) ➢ 5 toes on each foot ➢ 5 toes on each foot ➢ toes spread widely ➢ toes close together ➢ toes long and finger shaped ➢ toes short and round ➢ no claw mark on hind thumbs ➢ some partially webbed Mice, Squirrels, etc. (Rodent Family) Deer ➢ 4 toes on front feet, 5 toes on hind ➢ 2 toes on each foot feet ➢ tracks are paired when bounding ➢ front feet show dew claws ➢ hind feet step in fore feet ➢ size of track is important in separating species tracks ➢ may leave tail mark Walking Gaits Pace Diagonal Walk (Raccoon) (Dog Family, Cat, Deer, Opossum) Move both left feet together, Left front, right hind, right then both right feet front, left hind Bound Gallop (Weasel Family) (Rodent Family, Rabbit) Move both front feet together, Move both feet together, then then both hind feet move both hind feet Place hind feet behind front feet Place hind feet ahead of front feet . -

Species Richness, Endemism, and the Choice of Areas for Conservation

Species Richness, Endemism, and the Choice of Areas for Conservation JEREMY T. KERR Department of Biology, York University, 4700 Keele Street, North York, Ontario M3J 1P3, Canada, email [email protected] Abstract: Although large reserve networks will be integral components in successful biodiversity conserva- tion, implementation of such systems is hindered by the confusion over the relative importance of endemism and species richness. There is evidence (Prendergast et al. 1993) that regions with high richness for a taxon tend to be different from those with high endemism. I tested this finding using distribution and richness data for 368 species from Mammalia, Lasioglossum, Plusiinae, and Papilionidae. The study area, subdivided into 336 quadrats, was the continuous area of North America north of Mexico. I also tested the hypothesis that the study taxa exhibit similar diversity patterns in North America. I found that endemism and richness patterns within taxa were generally similar. Therefore, the controversy over the relative importance of endemism and species richness may not be necessary if an individual taxon were the target of conservation efforts. I also found, however, that richness and endemism patterns were not generally similar between taxa. Therefore, centering nature reserves around areas that are important for mammal diversity (the umbrella species con- cept) may lead to large gaps in the overall protection of biodiversity because the diversity and endemism of other taxa tend to be concentrated elsewhere. I investigated this further by selecting four regions in North America that might form the basis of a hypothetical reserve system for Carnivora. I analyzed the distribution of the invertebrate taxa relative to these regions and found that this preliminary carnivore reserve system did not provide significantly different protection for these invertebrates than randomly selected quadrats. -

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abalosia U.Pliocene S America Abelmoschomys U.Miocene E USA A

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abalosia U.Pliocene S America Abelmoschomys U.Miocene E USA A. simpsoni U.Miocene Florida(US) Abra see Ochotona Abrana see Ochotona Abrocoma U.Miocene-Recent Peru A. oblativa 60 cm? U.Holocene Peru Abromys see Perognathus Abrosomys L.Eocene Asia Abrothrix U.Pleistocene-Recent Argentina A. illuteus living Mouse Lujanian-Recent Tucuman(ARG) Abudhabia U.Miocene Asia Acanthion see Hystrix A. brachyura see Hystrix brachyura Acanthomys see Acomys or Tokudaia or Rattus Acarechimys L-M.Miocene Argentina A. minutissimus Miocene Argentina Acaremys U.Oligocene-L.Miocene Argentina A. cf. Murinus Colhuehuapian Chubut(ARG) A. karaikensis Miocene? Argentina A. messor Miocene? Argentina A. minutissimus see Acarechimys minutissimus Argentina A. minutus Miocene? Argentina A. murinus Miocene? Argentina A. sp. L.Miocene Argentina A. tricarinatus Miocene? Argentina Acodon see Akodon A. angustidens see Akodon angustidens Pleistocene Brazil A. clivigenis see Akodon clivigenis Pleistocene Brazil A. internus see Akodon internus Pleistocene Argentina Acomys L.Pliocene-Recent Africa,Europe,W Asia,Crete A. cahirinus living Spiny Mouse U.Pleistocene-Recent Israel A. gaudryi U.Miocene? Greece Aconaemys see Pithanotomys A. fuscus Pliocene-Recent Argentina A. f. fossilis see Aconaemys fuscus Pliocene Argentina Acondemys see Pithanotomys Acritoparamys U.Paleocene-M.Eocene W USA,Asia A. atavus see Paramys atavus A. atwateri Wasatchian W USA A. cf. Francesi Clarkforkian Wyoming(US) A. francesi(francesci) Wasatchian-Bridgerian Wyoming(US) A. wyomingensis Bridgerian Wyoming(US) Acrorhizomys see Clethrionomys Actenomys L.Pliocene-L.Pleistocene Argentina A. maximus Pliocene Argentina Adelomyarion U.Oligocene France A. vireti U.Oligocene France Adelomys U.Eocene France A. -

Mammalia, Notoungulata), from the Eocene of Patagonia, Argentina

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org An exceptionally well-preserved skeleton of Thomashuxleya externa (Mammalia, Notoungulata), from the Eocene of Patagonia, Argentina Juan D. Carrillo and Robert J. Asher ABSTRACT We describe one of the oldest notoungulate skeletons with associated cranioden- tal and postcranial elements: Thomashuxleya externa (Isotemnidae) from Cañadón Vaca in Patagonia, Argentina (Vacan subage of the Casamayoran SALMA, middle Eocene). We provide body mass estimates given by different elements of the skeleton, describe the bone histology, and study its phylogenetic position. We note differences in the scapulae, humerii, ulnae, and radii of the new specimen in comparison with other specimens previously referred to this taxon. We estimate a body mass of 84 ± 24.2 kg, showing that notoungulates had acquired a large body mass by the middle Eocene. Bone histology shows that the new specimen was skeletally mature. The new material supports the placement of Thomashuxleya as an early, divergent member of Toxodon- tia. Among placentals, our phylogenetic analysis of a combined DNA, collagen, and morphology matrix favor only a limited number of possible phylogenetic relationships, but cannot yet arbitrate between potential affinities with Afrotheria or Laurasiatheria. With no constraint, maximum parsimony supports Thomashuxleya and Carodnia with Afrotheria. With Notoungulata and Litopterna constrained as monophyletic (including Macrauchenia and Toxodon known for collagens), these clades are reconstructed on the stem -

Quaternary International Colonisation and Early Peopling of The

Quaternary International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa ∗ Gaspar Morcote-Ríosa, Francisco Javier Aceitunob, , José Iriartec, Mark Robinsonc, Jeison L. Chaparro-Cárdenasa a Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia b Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia c Department of Archaeology, Exeter, University of Exeter, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Recent research carried out in the Serranía La Lindosa (Department of Guaviare) provides archaeological evi- Colombian amazon dence of the colonisation of the northwest Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene. Preliminary ex- Serranía La Lindosa cavations were conducted at Cerro Azul, Limoncillos and Cerro Montoya archaeological sites in Guaviare Early peopling Department, Colombia. Contemporary dates at the three separate rock shelters establish initial colonisation of Foragers the region between ~12,600 and ~11,800 cal BP. The contexts also yielded thousands of remains of fauna, flora, Human adaptability lithic artefacts and mineral pigments, associated with extensive and spectacular rock pictographs that adorn the Rock art rock shelter walls. This article presents the first data from the region, dating the timing of colonisation, de- scribing subsistence strategies, and examines human adaptation to these transitioning landscapes. The results increase our understanding of the global expansion of human populations, enabling assessment of key inter- actions between people and the environment that appear to have lasting repercussions for one of the most important and biologically diverse ecosystems in the world. -

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics (a) (b) PLATE 2-1 (a) Coquerel’s Sifaka (Propithecus coquereli), a lemur species common to low-elevation, dry deciduous forests in Madagascar. (b) Ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) are highly social. PowerPoint Tips (Refer to the Microsoft Help feature for specific questions about PowerPoint. Copyright The Princeton University Press. Permission required for reproduction or display. FIGURE 2-1 This map shows the major biogeographic regions of the world. Each is distinct from the others because each has various endemic groups of plants and animals. FIGURE 2-2 Wallace’s Line was originally developed by Alfred Russel Wallace based on the distribution of animal groups. Those typical of tropical Asia occur on the west side of the line; those typical of Australia and New Guinea occur on the east side of the line. FIGURE 2-3 Examples of animals found on either side of Wallace’s Line. West of the line, nearer tropical Asia, one 3 nds species such as (a) proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus), (b) 3 ying lizard (Draco sp.), (c) Bornean bristlehead (Pityriasis gymnocephala). East of the line one 3 nds such species as (d) yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea), (e) various tree kangaroos (Dendrolagus sp.), and (f) spotted cuscus (Spilocuscus maculates). Some of these species are either threatened or endangered. PLATE 2-2 These vertebrate animals are each endemic to the Galápagos Islands, but each traces its ancestry to animals living in South America. (a) and (b) Galápagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra). These two images show (a) a saddle-shelled tortoise and (b) a dome-shelled tortoise.