Multicenter Case Series of Patients with Small-Bowel Angiodysplasias Treated with a Small-Bowel Radiofrequency Ablation Catheter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provocative Testing and Localization in Video Capsule Endoscopy

1 2 The Role of Provocative 3 4 Testing and Localization of 5 6 the Video Capsule Endoscope in 7 the Management of Small 8 9 Intestinal Bleeding Q4 10 11 a, b 12 Daniel L. Raines, MD *, Douglas G. Adler, MD Q5 Q6 Q7 13 Q1 Q2 14 15 KEYWORDS 16 Small intestinal bleeding Provocative angiography Provocative endoscopy 17 Video capsule endoscopy Device-assisted enteroscopy 18 19 20 KEY POINTS 21 Cases of small intestinal bleeding (SIB) are commonly encountered in clinical practice 22 despite advancements in medical technology that allow consistent visualization of the 23 entire gastrointestinal tract. 24 The use of antithrombotic agents to provoke bleeding has been found to be revealing in 25 cases of SIB when used in combination with angiography as well as endoscopy. 26 The performance of endoscopic procedures, including video capsule endoscopy (VCE) 27 and device-assisted enteroscopy (DAE) on active antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant ther- 28 apy is considered low risk and may improve diagnostic yield. 29 The use of VCE for gastrointestinal bleeding in the inpatient setting has been found to 30 improve diagnostic yield and decrease hospital stay. 31 Because DAE is required for therapeutic intervention in patients with small bowel 32 bleeding, access to this technology is essential for effective management in many cases. 33 34 35 Video content accompanies this article at http://www.giendo.theclinics.com/. 36 37 Q8 38 OBSCURE GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING Definitions 39 40 Small intestinal bleeding (SIB) has been described as bleeding that is undefined in 41 cause despite evaluation by standard upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, and small Q9 42 bowel follow-through (SBFT). -

Chapter 156: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

8/23/2018 Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine, 2e > Chapter 156: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Stephen R. Rotman; John R. Saltzman INTRODUCTION Key Clinical Questions What is the timing and treatment of peptic ulcer disease? What are the factors in diagnosis and treatment of aortoenteric fistula? What treatments are available for each etiology of upper GI bleeding? What is the appropriate management and follow-up of variceal bleeding? How do you estimate the severity of bleeding so that you can triage appropriate patients to the ICU, medical floor, or observation unit? Which patients are more likely to rebleed and hence require continued observation in the hospital aer their bleeding has apparently stopped, and for how long? Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is responsible for over 300,000 hospitalizations per year in the United States. An additional 100,000 to 150,000 patients develop upper GI bleeding during hospitalizations. The annual cost of treating nonvariceal acute upper GI bleeding in the United States exceeds $7 billion. Upper GI bleeding is defined as a bleeding source in the GI tract proximal to the ligament of Treitz. The presentation varies depending on the nature and severity of bleeding and includes hematemesis, melena, hematochezia (in rapid upper GI bleeding), and anemia with heme-positive stools. Bleeding can be associated with changes in vital signs, including tachycardia and hypotension including orthostatic hypotension. Given the range of presentations, pinpointing the nature and severity of GI bleeding may be a challenging task. The natural history of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding is that 80% of patients will stop bleeding spontaneously and no further urgent intervention will be needed. -

ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding

nature publishing group PRACTICE GUIDELINES 1265 CME ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding L a u r e n B . G e r s o n , M D , M S c , F A C G1 , J e ff L. Fidler , MD 2 , D a v i d R . C a v e , M D , P h D , F A C G 3 a n d J o n a t h a n A . L e i g h t o n , M D , F A C G 4 Bleeding from the small intestine remains a relatively uncommon event, accounting for ~5–10% of all patients presenting with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Given advances in small bowel imaging with video capsule endoscopy (VCE), deep enteroscopy, and radiographic imaging, the cause of bleeding in the small bowel can now be identifi ed in most patients. The term small bowel bleeding is therefore proposed as a replacement for the previous classifi cation of obscure GI bleeding (OGIB). We recommend that the term OGIB should be reserved for patients in whom a source of bleeding cannot be identifi ed anywhere in the GI tract. A source of small bowel bleeding should be considered in patients with GI bleeding after performance of a normal upper and lower endoscopic examination. Second-look examinations using upper endoscopy, push enteroscopy, and/or colonoscopy can be performed if indicated before small bowel evaluation. VCE should be considered a fi rst-line procedure for small bowel investigation. Any method of deep enteroscopy can be used when endoscopic evaluation and therapy are required. -

Prevalence of Angiodysplasia Detected in Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Examinations

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.14353 Prevalence of Angiodysplasia Detected in Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Examinations Takumi Notsu 1 , Kyoichi Adachi 1 , Tomoko Mishiro 1 , Kanako Kishi 1 , Norihisa Ishimura 2 , Shunji Ishihara 3 1. Health Center, Shimane Environment and Health Public Corporation, Matsue, JPN 2. Second Department of Internal Medicine, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine, Izumo, JPN 3. Gastroenterology, Shimane University Hospital, Izumo, JPN Corresponding author: Kyoichi Adachi, [email protected] Abstract Background This study was performed to examine the prevalence of asymptomatic angiodysplasia detected in upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations and of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) suspected cases. Methodology The study participants were 5,034 individuals (3,206 males, 1,828 females; mean age 53.5 ± 9.8 years) who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination as part of a medical check-up. The presence of angiodysplasia was examined endoscopically from the pharynx to duodenal second portion. HHT suspected cases were diagnosed based on the presence of both upper gastrointestinal angiodysplasia and recurrent nasal bleeding episodes occurring in the subject as well as a first-degree relative. Results Angiodysplasia was endoscopically detected in 494 (9.8%) of the 5,061 subjects. Those with angiodysplasia lesions in the pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, and duodenum numbered 44, 4, 155, 322, and 12, respectively. None had symptoms of upper gastrointestinal bleeding or severe anemia. Subjects with angiodysplasia showed significant male predominance and were significantly older than those without. A total of 11 (0.2%) were diagnosed as HHT suspected cases by the presence of upper gastrointestinal angiodysplasia and recurrent epistaxis episodes from childhood in the subject as well as a first-degree relative. -

Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Cirrhosis: Work-Up and Management

Current Hepatology Reports (2019) 18:81–86 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-019-00452-6 MANAGEMENT OF CIRRHOTIC PATIENT (A CARDENAS AND P TANDON, SECTION EDITORS) Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Cirrhosis: Work-up and Management Sergio Zepeda-Gómez1 & Brendan Halloran1 Published online: 12 February 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) in patients with cirrhosis can be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Recent advances in the approach and management of this group of patients can help to identify the source of bleeding. While the work-up of patients with cirrhosis and OGIB is the same as with patients without cirrhosis, clinicians must be aware that there are conditions exclusive for patients with portal hypertension that can potentially cause OGIB. Recent Findings New endoscopic and imaging techniques are capable to identify sources of OGIB. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) allows direct examination of the small-bowel mucosa and deliver specific endoscopic therapy. Conditions such as ectopic varices and portal hypertensive enteropathy are better characterized with the improvement in visualization by these techniques. New algorithms in the approach and management of these patients have been proposed. Summary There are new strategies for the approach and management of patients with cirrhosis and OGIB due to new develop- ments in endoscopic techniques for direct visualization of the small bowel along with the capability of endoscopic treatment for different types of lesions. Patients with cirrhosis may present with OGIB secondary to conditions associated with portal hypertension. Keywords Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding . Cirrhosis . Portal hypertension . -

Angiodysplasia of Colon Or GI Tract

Angiodysplasia of Colon or GI Tract Background Phillips first described a vascular (blood vessel) abnormality that caused bleeding from the large bowel in a letter to the London Medical Gazette in 1839. During the 1920s, cancers were considered the major source of GI bleeding/hemorrhage. However, in the 1940s and 1950s, diverticular disease was recognized as an important source of bleeding. In 1951, Smith described active bleeding from a diverticulum visualized through a sigmoidoscope. Galdabini first used the name angiodysplasia in 1974; however, confusion about the exact nature of these lesions resulted in a multitude of terms that included AVM = arteriovenous malformation, hemangioma, telangiectasia, and vascular ectasia. These terms have varying pathophysiologies, with a common presentation of GI bleeding and may be used interchangeably by many physicians. Angiodysplasia is a degenerative lesion of previously healthy blood vessels found most commonly in the right-side of colon. 77% of angiodysplasias are located in the cecum and ascending colon, 15% are located in the jejunum and ileum (small intestine), and the remainder are distributed throughout the GI tract. These lesions typically are nonpalpable and small (<5 mm). Angiodysplasia is the most common vascular abnormality of the GI tract. After diverticulosis, it is the second leading cause of lower GI bleeding in patients older than 60 years. Angiodysplasia may account for approximately 6% of cases of lower GI bleeding. It may be observed incidentally at colonoscopy in as many as 0.8% of patients older than 50 years. The prevalence for upper GI lesions is approximately 1-2%. Small bowel angiodysplasia may account for 30-40% of cases of GI bleeding of obscure origin. -

Crohn's Disease

Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology HST.121: Gastroenterology, Fall 2005 Instructors: Dr. Jonathan Glickman Vascular and Inflammatory Diseases of the Intestines Overview • Vascular disorders – Vascular “malformations” – Vasculitis – Ischemic disease • Inflammatory disorders of specific etiology – Infetious enterocolitis – “Immune-mediated” enteropathy – Diverticular disease • Idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease – Crohn’s disease – Ulcerative colitis Sporadic Vascular Ectasia (Telangiectasia) • Clusters of tortuous thin-walled small vessels lacking muscle or adventitia located in the mucosa and the submucosa • The most common type occurs in cecum or ascending colon of individuals over the age of 50 and is commonly known as “angiodysplasia” • Angiodysplasias account for 40% of all colonic vascular lesions and are the most common cause of lower GI bleeding in individuals over the age of 60 Angiodysplasia Hereditary Vascular Ectasia • Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) or Osler- Webber-Rendu disease • Systematic disease primarily involving skin and mucous membranes, and often the GI tract • Autosomal dominant disease with positive family history in 80% of cases • After epistaxis which occurs in 80% of individuals, GI bleed is the most frequent presentation and occurs in 10-40% of cases Arteriovenous Malformations (AVM’s) • Irregular meshwork of structurally abnormal medium to large ectatic vessels • Unlike small vessel ectasias, AVM’s can be distributed in all layers of the bowel wall • AVM’s may present anywhere -

Efficacy of Colonoscopy, Colon Capsule and Fecal Immunological Test For

Efficacy of colonoscopy, colon capsule and fecal immunological test for colorectal cancer screening, in first degree relatives of patients with colorectal neoplasia: a prospective randomized study - FAMCAP Study Version n°6 - Date: 2017-07-11 Sponsor: Hospices Civils de Lyon BP 2251 3 quai des Célestins 69229 LYON Cedex 02 - France Coordinator: Pr Jean-Christophe SAURIN Hepatogastroenterology - Pav. L Edouard Herriot Hospital - Hospices Civils de Lyon 5 Place d’Arsonval 69437 LYON Cedex 3 - FRANCE Phone: +33 (0)4 72 11 75 72; Fax: +33 (0)4 72 11 01 47 E-mail: [email protected] Methodologist: Pr Anne-Marie SCHOTT Pôle IMER - Hospices Civils de Lyon 162 avenue Lacassagne 69424 LYON Cedex 3 - FRANCE E-mail: [email protected] Sponsor code: 69HCL16_0091 ID-RCB number: 2016-A01097-44 Clinicaltrials.gov registration number: NCT02738359 Date of Ethics Committee (CPP Sud-Est III) approval: 2016-10-18 Abstract: Fecal immunological test (FIT) is the reference screening method in average risk patient. FIT is proposed every 2 years to all asymptomatic subjects with average risk aged from 50 to 74 years in France. Optical colonoscopy (OC) is the gold standard examination for patients at increased risk of colorectal cancer, like those with a first degree relative with colorectal cancer (relative risk between 2 and 4 times that of the general population). Colonoscopy should be performed in this high risk group before 50 years or 5 to 10 years before the earliest case of colorectal cancer. Optical colonoscopy has important limitations: complications (perforation, bleeding), need to use general anesthesia (in France 95% of colonoscopy are performed under general anesthesia), and low acceptability for screening even in high risk persons (40% in the best cases). -

Capsule Endoscopy

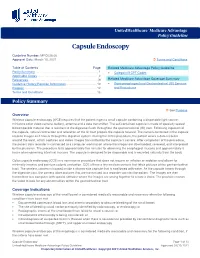

UnitedHealthcare® Medicare Advantage Policy Guideline Capsule Endoscopy Guideline Number: MPG036.06 Approval Date: March 10, 2021 Terms and Conditions Table of Contents Page Related Medicare Advantage Policy Guideline Policy Summary ............................................................................. 1 • Category III CPT Codes Applicable Codes .......................................................................... 3 References ..................................................................................... 9 Related Medicare Advantage Coverage Summary Guideline History/Revision Information ..................................... 10 • Gastroesophageal and Gastrointestinal (GI) Services Purpose ........................................................................................ 12 and Procedures Terms and Conditions ................................................................. 13 Policy Summary See Purpose Overview Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) requires that the patient ingest a small capsule containing a disposable light source, miniature color video camera, battery, antenna and a data transmitter. The self-contained capsule is made of specially sealed biocompatible material that is resistant to the digestive fluids throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Following ingestion of the capsule, natural contraction and relaxation of the GI tract propels the capsule forward. The camera contained in the capsule records images as it travels through the digestive system. During the entire procedure, the patient wears -

Clinical Impact of Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy in Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding

medicina Article Clinical Impact of Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy in Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding Ana-Maria Singeap 1,2 , Camelia Cojocariu 1,2,*, Irina Girleanu 1,2, Laura Huiban 1,2, Catalin Sfarti 1,2, Tudor Cuciureanu 1,2, Stefan Chiriac 1,2 , Carol Stanciu 2 and Anca Trifan 1,2 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 700115 Iasi, Romania; [email protected] (A.-M.S.); [email protected] (I.G.); [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (A.T.) 2 Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, “St. Spiridon” Emergency Hospital, 700111 Iasi, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-752223968 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 19 October 2020 Abstract: Background and objectives: The most frequent indications for small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) are obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) and iron deficiency anemia (IDA). The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic yield (DY) of SBCE in overt and occult OGIB, as well as its impact on the clinical outcome. Materials and Methods: This study retrospectively included all cases of OGIB investigated by SBCE in a tertiary care referral center, between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2018. OGIB was defined by overt or occult gastrointestinal bleeding, with negative upper and lower endoscopy. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding was either proved by a fecal test or presumptively incriminated as a cause for IDA. DY was defined as the detection rate for what were thought to be clinically significant findings. -

Capsule Endoscopy

CLINICAL MEDICAL POLICY Policy Name: Capsule Endoscopy Policy Number: MP-038-MD-PA Responsible Department(s): Medical Management Provider Notice Date: 02/17/2020 Issue Date: 02/17/2020 Effective Date: 03/16/2020 Annual Approval Date: 12/2020 Revision Date: 12/18/2019 Products: Gateway Health℠ Medicaid Application: All participating hospitals and providers Page Number(s): 1 of 12 DISCLAIMER Gateway Health℠ (Gateway) medical policy is intended to serve only as a general reference resource regarding coverage for the services described. This policy does not constitute medical advice and is not intended to govern or otherwise influence medical decisions. POLICY STATEMENT Gateway Health℠ provides coverage under the medical-surgical benefits of the Company’s Medicaid products for medically necessary capsule endoscopy procedures. This policy is designed to address medical necessity guidelines that are appropriate for the majority of individuals with a particular disease, illness or condition. Each person’s unique clinical circumstances warrant individual consideration, based upon review of applicable medical records. (Current applicable Pennsylvania HealthChoices Agreement Section V. Program Requirements, B. Prior Authorization of Services, 1. General Prior Authorization Requirements.) Policy No. MP-038-MD-PA Page 1 of 12 DEFINITIONS Prior Authorization Review Panel (PARP) – A panel of representatives from within the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services who have been assigned organizational responsibility for the review, approval and denial of all PH-MCO Prior Authorization policies and procedures. Gastric Emptying Scintigraphy – A diagnostic test where the individual ingests a radionuclide-labeled standard meal, and then images are taken at 0, 1, 2, and 4 hours postprandial in order to measure how much of the meal has passed beyond the stomach. -

Heyde's Syndrome

Cease Report Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol Volume 2 Issue 4 - January 2017 DOI: 10.19080/ARGH.2017.04.555592 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Deepankar Kumar Basak Heyde’s syndrome: Rarely heard and often missed Deepankar Kumar Basak1*, Richmond Ronald Gomes2 and Md Samsul Arfin3 1Specialist-Gastroenterology, Square Hospitals Ltd., Bhangladesh 2Assistant Professor, Internal Medicine, Ad-din Sakina Medical College & Hospital, Bhangladesh 3Gasroenterology, Square Hospitals Limited., Bhangladesh Submission: November 11, 2016; Published: January 19, 2017 *Corresponding author: Deepankar Kumar Basak, MBBS, FCPS (Medicine), Specialist-Gastroenterology, Square Hospital Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh, Tel: Email: Abstract Bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract is very common and important problem in clinical practice. There are lots of causes of GI bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding in an elderly female patient who is also suffering from HCV related decompensated CLD with multiple myeloma. Heyde’sbut sometimes syndrome it is is very now difficult known to belocate gastrointestinal and treat gastrointestinal bleeding from bleeding. angiodysplasic Here we lesions discuss due Heyde’s to acquired syndrome, vWD-2A an secondaryimportant tocause aortic of stenosis, and the diagnosis is made by confirming the presence of those three things. For this, a wide range of investigations and treatment showingmodalities gastrointestinal are now available. bleeding One aftershould aortic therefore valve makereplacement. an aggressive Old age attempt and co-morbidities to localize the may bleeding create site.a hindrance Newer endoscopic in valve replacement technologies or resectionmay prove surgery. beneficial. Some Aortic newer valve treatment replacement options is claimed like hormonal to minimize and orthalidomide even stop thetherapy bleeding look in promising such patients.