Mozart, Pergolesi, Handel?: a Study of Three Forgeries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759)

Hey Kids, Meet George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759) George Frideric Handel was born on February 23, 1685 in the North German province of Saxony, in the same year as Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. George's father wanted him to be a lawyer, though music had captivated his attention. His mother, in contrast, supported his interest in music, and he was allowed to take keyboard and music composition lessons. His aunt gave him a harpsichord for his seventh birthday which Handel played whenever he had the chance. In 1702 Handel followed his father's wishes and began his study of law at the University of Halle. After his father's death in the following year, he returned to music and accepted a position as the organist at the Protestant Cathedral. In the next year he moved to Hamburg and accepted a position as a violinist and harpsichordist at the opera house. It was there that Handel's first operas were written and produced. In 1710, Handel accepted the position of Kapellmeister to George, Elector of Hanover, who was soon to be King George I of Great Britain. In 1712 he settled in England where Queen Anne gave him a yearly income. In the summer of 1717, Handel premiered one of his greatest works, Water Music, in a concert on the River Thames. The concert was performed by 50 musicians playing from a barge positioned closely to the royal barge from which the King listened. It was said that King George I enjoyed it so much that he requested the musicians to play the suite three times during the trip! By 1740, Handel completed his most memorable work - the Messiah. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

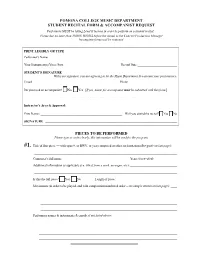

Student Recital/Accompanist Request Form

POMONA COLLEGE MUSIC DEPARTMENT STUDENT RECITAL FORM & ACCOMPANIST REQUEST Performers MUST be taking Level II lessons in order to perform on a student recital. Forms due no later than THREE WEEKS before the recital to the Concert Production Manager Incomplete forms will be returned. PRINT LEGIBLY OR TYPE Performer’s Name:__________________________________________________________________________________ Your Instrument(s)/Voice Part: Recital Date: _________________________ STUDENT’S SIGNATURE _________________________________________________________________________ With your signature, you are agreeing to let the Music Department live-stream your performance. Email _____________________________________________________ Phone ______________________________ Do you need an accompanist? •No •Yes [If yes, music for accompanist must be submitted with this form.] ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Instructor’s Area & Approval: Print Name: ____________________________________________________ Will you attend the recital? •Yes •No SIGNATURE ____________________________________________________________________________________ PIECES TO BE PERFORMED Please type or write clearly, this information will be used for the program. #1. Title of first piece — with opus #, or BWV, or year composed or other such notation (See guide on last page): ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Composer’s full name: _________________________________________ Years (born–died): ______________ -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015 1. How did you find out about this survey? Other 17% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% 539 Other 17.0% 110 Total 649 1 2. Where are you from? Australia/New Zealand 3.2% Asia 3.7% Europe 7.9% North America 85.2% North America 85.2% 553 Europe 7.9% 51 Asia 3.7% 24 Australia/New Zealand 3.2% 21 Total 649 2 3. What is your age range? old fart like me 15.4% 21-30 22% 51-60 23.3% 31-40 16.8% 41-50 22.5% Statistics 21-30 22.0% 143 Sum 20,069.0 31-40 16.8% 109 Average 36.6 41-50 22.5% 146 StdDev 11.5 51-60 23.3% 151 Max 51.0 old fart like me 15.4% 100 Total 649 3 4. How many fountain pens are in your collection? 1-5 23.3% over 20 35.8% 6-10 23.9% 11-20 17.1% Statistics 1-5 23.3% 151 Sum 2,302.0 6-10 23.9% 155 Average 5.5 11-20 17.1% 111 StdDev 3.9 over 20 35.8% 232 Max 11.0 Total 649 4 5. How many pens do you usually keep inked? over 10 10.3% 7-10 12.6% 1-3 40.7% 4-6 36.4% Statistics 1-3 40.7% 264 Sum 1,782.0 4-6 36.4% 236 Average 3.1 7-10 12.6% 82 StdDev 2.1 over 10 10.3% 67 Max 7.0 Total 649 5 6. -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown. -

This Is Normal Text

AN EXAMINATION OF WORKS FOR SOPRANO: “LASCIA CH’IO PIANGA” FROM RINALDO, BY G.F. HANDEL; NUR WER DIE SEHNSUCHT KENNT, HEISS’ MICH NICHT REDEN, SO LASST MICH SCHEINEN, BY FRANZ SCHUBERT; AUF DEM STROM, BY FRANZ SCHUBERT; SI MES VERS AVAIENT DES AILES, L’ÉNAMOURÉE, A CHLORIS, BY REYNALDO HAHN; “ADIEU, NOTRE PETITE TABLE” FROM MANON, BY JULES MASSENET; HE’S GONE AWAY, THE NIGHTINGALE, BLACK IS THE COLOR OF MY TRUE LOVE’S HAIR, ADAPTED AND ARRANGED BY CLIFFORD SHAW; “IN QUELLE TRINE MORBIDE” FROM MANON LESCAUT, BY GIACOMO PUCCINI by ELIZABETH ANN RODINA B.M., KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY, 2006 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Jennifer Edwards Copyright ELIZABETH ANN RODINA 2008 Abstract This report consists of extended program notes and translations for programmed songs and arias presented in recital by Elizabeth Ann Rodina on April 22, 2008 at 7:30 p.m. in All Faith’s Chapel on the Kansas State University campus. Included on the recital were works by George Frideric Handel, Franz Schubert, Reynaldo Hahn, Jules Massenet, Clifford Shaw, and Giacomo Puccini. The program notes include biographical information about the composers and a textual and musical analysis of their works. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. -

Monoline Quill

MONOLINE Monoline pen is a high quality gel pen. It is the more affordable of the two options; however, we do not recommend it on shimmer paper or dark envelopes as it does not show true to color. It can also appear streaky on those paper finishes. Monoline ink cannot be mixed to match specific colors. I have attached a photo to show you what monoline pen would look like. As you can see from the photo, there is no variation in line weight. QUILL Quill is the traditional calligrapher's pen. It uses a metal nib that is dipped in an ink bottle before each stroke. It is the more luxurious of the options. On certain paper, you can feel the texture of the ink once it dries. Quill ink can also be mixed to match certain colors. As you can see from the photo, there is variation in line weight. Disclaimer: The majority of our pieces are individually handmade and handwritten (unless it is a printed mass production) therefore, the artwork in each piece will look different from each other. ORIGINAL Original has the standard amount of flourishes. CLEAN Clean has the least amount of flourishes. Disclaimer: The majority of our pieces are individually handmade and handwritten (unless it is a printed mass production) therefore, the artwork in each piece will look different from each other. FLOURISHED Extra flourishes are added. Fonts that can be flourished: **Royale, Eloise, Francisca, Luisa, and Theresa Classic UPRIGHT & ITALICIZED All fonts can be written upright or italicized. Disclaimer: The majority of our pieces are individually handmade and handwritten (unless it is a printed mass production) therefore, the artwork in each piece will look different from each other. -

The Origins of the Musical Staff

The Origins of the Musical Staff John Haines For Michel Huglo, master and friend Who can blame music historians for frequently claiming that Guido of Arezzo invented the musical staff? Given the medieval period’s unma- nageable length, it must often be reduced to as streamlined a shape as possible, with some select significant heroes along the way to push ahead the plot of musical progress: Gregory invented chant; the trouba- dours, vernacular song; Leoninus and Perotinus, polyphony; Franco of Cologne, measured notation. And Guido invented the staff. To be sure, not all historians put it quite this way. Some, such as Richard Hoppin, write more cautiously that “the completion of the four-line staff ...is generally credited to Guido d’Arezzo,”1 or, in the words of the New Grove Dictionary of Music, that Guido “is remembered today for his development of a system of precise pitch notation through lines and spaces.”2 Such occasional caution aside, however, the legend of Guido as inventor of the staff abides and pervades. In his Notation of Polyphonic Music, Willi Apel writes of “the staff, that ingenious invention of Guido of Arezzo.”3 As Claude Palisca puts it in his biography of Guido, it was that medieval Italian music writer’s prologue to his antiphoner around 1030 that contained one of the “brilliant proposals that launched the Guido legend, the device of staff notation.”4 “Guido’s introduction of a system of four lines and four spaces” is, in Paul Henry Lang’s widely read history, an “achievement” deemed “one of the most significant in -

Teacher Requisition Form

81075 Detach and photocopy—then give everyone their own form! Teacher Requisition Form Stop looking up individual items–our best-selling school supplies are all right here! Just fill in the quantity you want and total price! Here’s how to use this Teacher Requisition Form: 1. Distribute copies of this form to everyone making an order 2. For each item, fill in the quantity needed and the extended price 3. Attach completed Teacher Requisition Forms to your purchase order and account information, and return to Quill Important note: First column pricing 4. Attention School Office: We can hold your order for up to is shown on this form. 120 days and automatically release it and bill you on the day Depending on the total you specify. Just write Future Delivery on your purchase quantity ordered, your order, the week you want your order to ship, your receiving price may be even lower! hours and any special shipping instructions. Attach the Requisition Forms to your purchase order and account information Teacher Name:________________ School:__________________________ Account #: _________________ Email Address: Qty. Item Unit Total Qty. Item Unit Total Ord. Unit Number Description Price Price Ord. Unit Number Description Price Price ® PENCILS DZ 60139 uni-ball Vision, Fine, Red 18.99 DZ 60382 uni-ball® Vision, Fine, Purple 18.99 DZ T8122 Quill® Finest Quality Pencils, #2 1.89 DZ 60386 uni-ball® Vision, Fine, Green 18.99 DZ T812212 Quill® Finest Quality Pencils, #2.5 1.89 DZ 60387 uni-ball® Vision, Fine, Asst’d. Colors 18.99 DZ T8123 Quill® Finest Quality Pencils, #3 1.89 DZ 732158 Quill® Visible Ink Rollerball, Blue 9.99 DZ T7112 Quill® Standard-Grade Pencils, #2 1.09 DZ 732127 Quill® Visible Ink Rollerball, Black 9.99 DZ 13882 Ticonderoga® Pencils, #2 2.09 DZ 732185 Quill® Visible Ink Rollerball, Red 9.99 DZ 13885 Ticonderoga® Pencils, #2.5 2.09 DZ 84101 Flair Pens, Blue 13.99 DZ 13913 Ticonderoga® Pencils, #2, Black Fin. -

Making a Quill Pen This Activity May Need a Little Bit of Support However the End Project Will Be Great for Future Historic Events and Other Crafting Activities

Making A Quill Pen This activity may need a little bit of support however the end project will be great for future historic events and other crafting activities. Ask your maintenance person to get involved by providing the pliers and supporting with the production of the Quill Pen. What to do 1. Use needle-nose pliers to cut about 1" off of the pointed end of the turkey feather. 2. Use the pliers to pluck feathers from the quill as shown in the first photo on the next page. Leave about 6" of feathers at the top of the quill. 3. Sand the exposed quill with an emery board to remove flaky fibres and unwanted texture. Smoothing the quill will make it more pleasant to hold while writing. 4. If the clipped end of the quill is jagged and/or split, carefully even it out using nail scissors as shown in the middle photo. 5. Use standard scissors to make a slanted 1/2" cut on the tip of the quill as shown in the last photo below. You Will Need 10" –12" faux turkey feather Water -based ink 6. Use tweezers to clean out any debris left in the hollow of the quill. Needle -nose pliers 7. Cut a 1/2" vertical slit on the long side of the quill tip. When the Emery board pen is pressed down, the “prongs” should spread apart slightly as Nail scissors shown in the centre photo below. Tweezers Scissors Keeping it Easy Attach a ball point pen to the feather using electrical tape. -

Pen and Ink 3 Required Materials

Course: Pen and Ink 3 Required materials: 1. Basic drawing materials for preparatory drawing: • A few pencils (2H, H, B), eraser, pencil sharpener 2. Ink: • Winsor & Newton black Indian ink (with a spider man graphic on the package) This ink is shiny, truly black, and waterproof. Do not buy ‘calligraphy ink’. 3. Pen nibs & Pen holders : Pen nibs are extremely confusing to order online, and packages at stores have other nibs which are not used in class. Therefore, instructor will bring two of each nib and 1nib holders for each number, so students can buy them in the first class. Registrants need to inform the instructor if they wish to buy it in the class. • Hunt (Speedball) #512 Standard point dip pen and pen holder • Hunt (Speedball) # 102 Crow quill dip pen • Hunt (Speedball) # 107 Stiff Hawk Crow quill nib 4. Paper: • Strathmore Bristol Board, Plate, 140Lb (2-ply), (Make sure it is Plate surface- No vellum surface!) Pad seen this website is convenient: http://www.dickblick.com/products/strathmore-500-series-bristol-pads/ One or two sheets will be needed for each class. • Bienfang 360 Graphic Marker for preparatory drawing and tracing. Similar size with Bristol Board recommended http://www.dickblick.com/products/bienfang-graphics-360-marker-paper/ 5. Others: • Drawing board: Any board that can firmly hold drawing paper (A tip: two identical light weight foam boards serve perfectly as a drawing board, and keep paper safely in between while traveling.) * Specimen holder (frog pin holder, a small jar, etc.), a small water jar for washing pen nib) • Divider, ruler, a role of paper towel For questions, email Heeyoung at [email protected] or call 847-903-7348.