TOC 0368 CD Booklet.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), Piano

MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WIND ENSEMBLE Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Conductor Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano PROGRAM JOHN WILLIAMS For New York (b. 1932) (Trans. for band by Paul Lavender) FRANK TICHELI Acadiana (b. 1958) At the Dancehall Meditations on a Cajun Ballad To Lafayette IGOR ST R AVINSKY Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1882–1971) Lento; Allegro Largo Allegro Joseph Mohan (DMA ’21), piano Intermission VITTORIO Symphony No. 3 for Band GIANNINI Allegro energico (1903–1966) Adagio Allegretto Allegro con brio CENTENNIAL NOTE Vittorio Giannini (1903–1966) was an Italian-American composer calls upon the band’s martial associations, with an who joined the Manhattan School of Music faculty in 1944, where he exuberant march somewhat reminiscent of similar taught theory and composition until 1965. Among his students were efforts by Sir William Walton. Along with the sunny John Corigliano, Nicolas Flagello, Ludmila Ulehla, Adolphus Hailstork, disposition and apparent straightforwardness of works Ursula Mamlok, Fredrick Kaufman, David Amram, and John Lewis. like the Second and Third Symphonies, the immediacy MSM founder Janet Daniels Schenck wrote in her memoir, Adventure and durability of their appeal is the result of considerable in Music (1960), that Giannini’s “great ability both as a composer and as subtlety in motivic and harmonic relationships and even a teacher cannot be overestimated. In addition to this, his remarkable in voice leading. personality has made him beloved by all.” In addition to his Symphony No. -

CRI 272 VITTORIO GIANNINI the TAMING of the SHREW Opera in Three Acts

CRI 272 VITTORIO GIANNINI THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Opera in Three Acts An adaptation of Shakespeare's play, with additional texts from his sonnets and “Romeo and Juliet” by the composer and Dorothy Fee presented by the KANSAS CITY LYRIC THEATER Russell Patterson, musical director Cast of Characters (in order of appearance) Lucentio, a young nobleman Lowell Harris Tranio, his servant David Holloway Baptista, a prosperous merchant J. B. Davis Katharina, his eldest daughter Mary Jennings Bianca, Katharina's sister Catherine Christensen Gremio, suitor of Bianca Robert Jones Hortensio, suitor of Bianca Walter Hook Biondello, servant of Lucentio Brian Steele Petruchio, gentleman of Verona Adair McGowen Grumio, his servant Charles Weedman A Tailor Stephen Knott Curtis, Katharina's servant William Latimer Vincentio, Lucentio's father William Powers An Actor Donald Nelson THE STORY Act. I. Strolling with his servant Tranio, the rich, young Lucentio, recently come to Padua to round out his education, secretly witnesses a strenuous argument, between the prosperous merchant Baptista and his two beautiful daughters and two suitors. Katharina, the elder, has such a violent temper that no one will consider marrying her; Bianca, the younger, is so gentle and amiable that she, has two suitors Gremio and Hortensio. Baptista declares that he will not permit Bianca to marry until Katharina has a husband. So Bianca's suitors have to find someone who will marry the shrew Katharina. Promptly, Lucentio also falls in love with Bianca. He devises a scheme to exchange identity and costume with Tranio who will assist his master's wooing while Lucentio will try to be hired as a tutor for Bianca. -

Unifying Elements of John Corigliano's

UNIFYING ELEMENTS OF JOHN CORIGLIANO'S ETUDE FANTASY By JANINA KUZMAS Undergraduate Diploma with honors, Sumgait College of Music, USSR, 1985 B. Mus., with the highest honors, Vilnius Conservatory, Lithuania, 1991 Performance Certificate, Lithuanian Academy of Music, 1993 M. Mus., Bowling Green State University, USA, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 2002 © Janina Kuzmas 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. ~':<c It CC L Department of III -! ' The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date J/difc-L DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT John Corigliano's Etude Fantasy (1976) is a significant and challenging addition to the late twentieth century piano repertoire. A large-scale work, it occupies a particularly important place in the composer's output of music for piano. The remarkable variety of genres, styles, forms, and techniques in Corigliano's oeuvre as a whole is also evident in his piano music. -

Department of Music Programs 1968 - 1969 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 1969 Department of Music Programs 1968 - 1969 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 1968 - 1969" (1969). School of Music: Performance Programs. 1. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 8 0 . 7 3 9 O M p 1 9 6 8 - 6 9 PROGRAMS 1968-69 7 $ e . DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC i u M a OLIVET NAZARENE COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC presents SENIOR RECITAL GEORGENE FISH PIANO AND CALBERT HOLSTE I N TENOR PHYLLIS HOLSTEIN/ ACCOMPANIST Lasciatemi morire, "Ariana"0oe.....0Claudio Monteverdi Dove sei, amato bene?, "Rodelinda".0o.George F 0 Handel If With All Your Hearts, "Elijah"....Felix Mendelssohn Prelude and Fugue, No. 3.0o...o..Johann Sebastian Bach Fantasia in D minor 0 D 0«».,«5.«.Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Viens Aurore..ooooooooooooooooooooooooooo.c.o Arro A o L . F el d e m s a m k e i t oooooooo..o.o.oooo..oo.. odohannes Brahms Du bist wie Eine BlumeDo,...t.t....o««Anton Rubenstein M*appari tut" amor, "Martha".....Friedrich von Flowtow Mouvements Perpetuels for Piano........Francis Poulenc I. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Weekend Movie Schedule Pictures Fuel Fantasies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, February 24, 2006 5 sick. Your concerns about the baby are MONDAY EVENING FEBRUARY 27, 2006 justified, and you have kept this secret too 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 long. Please tell the parents-to-be so they E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Pictures fuel fantasies Flip House House flip. Confronting Evil: America Rollergirls: Searching for Crossing Jordan (TV14) Flip House House flip. can protect their little one from your 36 47 A&E (TVPG) Undercover Ann Calvello (HD) (TVPG) mother. Because you are afraid you may DEAR ABBY: I was visiting my abigail Wife Swap: Schachtner/ The Bachelor: Paris Travis chooses his mate in the KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel not be believed, start out this way: “You 4 6 ABC Martincak (N) season finale. (N) at 10 (N) (TV14) friend, “Carla,” last week and arrived a van buren may have wondered why I don’t get Animal Cops: Down and In Animal Cops - Detroit: Animal Precinct: Too Late Animal Cops: Down and In Animal Cops - Detroit: little early on our way to go shopping. 26 54 ANPL along with Mother. This is the reason — Danger (TVPG) Wounded by Wire (TV G) Danger (TVPG) Wounded by Wire While I was waiting for her to dress, I The West Wing: Internal Kathy Griffin: The D-List Outrageous Outrageous Project Runway: What’s Outrageous Outrageous and I’m worried about the safety of your 63 67 BRAVO noticed some photographs on her kitchen Displacement (HD) Celebrity culture. -

Hallmark Collection

Hallmark Collection 20000 Leagues Under The Sea In 1867, Professor Aronnax (Richard Crenna), renowned marine biologist, is summoned by the Navy to identify the mysterious sea creature that disabled the steamship Scotia in die North Atlantic. He agrees to undertake an expedition. His daughter, Sophie (Julie Cox), also a brilliant marine biologist, disguised as a man, comes as her father's assistant. On ship, she becomes smitten with harpoonist Ned Land (Paul Gross). At night, the shimmering green sea beast is spotted. When Ned tries to spear it, the monster rams their ship. Aronnax, Sophie and Ned are thrown overboard. Floundering, they cling to a huge hull which rises from the deeps. The "sea beast" is a sleek futuristic submarine, commanded by Captain Nemo. He invites them aboard, but warns if they enter the Nautilus, they will not be free to leave. The submarine is a marvel of technology, with electricity harnessed for use on board. Nemo provides his guests diving suits equipped with oxygen for exploration of die dazzling undersea world. Aronnax learns Nemo was destined to be the king to lead his people into the modern scientific world, but was forced from his land by enemies. Now, he is hoping to halt shipping between the United States and Europe as a way of regaining his throne. Ned makes several escape attempts, but Sophie and her father find the opportunities for scientific study too great to leave. Sophie rejects Nemo's marriage proposal calling him selfish. He shows his generosity, revealing gold bars he will drop near his former country for pearl divers to find and use to help the unfortunate. -

Movielistings

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, June 8, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESDAY’S SATURDAY EVENING JUNE 9, 2007 SUNDAY EVENING JUNE 10, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Family (TV14) Family Jewels Family Jewels Family Jewels Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Flip This House: Roach Flip This House: Burning Star Wars: Empire of Dreams The profound effects of Flip This House: Roach 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E House (TV G) (R) Down the House Star Wars. (TVPG) House (TV G) (R) (R) (R) (N) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) F. -

View Commencement Program

THOSE WHO EXCEL REACH THE STARS FRIDAY, MAY 10, 2019 THE RIVERSIDE CHURCH MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC NINETY-THIRD COMMENCEMENT Processional The audience is requested to rise and remain standing during the processional. ANTHONY DILORENZO “The Golden Palace and the Steamship” from The Toymaker (b. 1967) WILLIAM WALTON Crown Imperial: Coronation March (1902–1983) (arr. J. Kreines) BRIAN BALMAGES Fanfare canzonique (b. 1975) Commencement Brass and Percussion Ensemble Kyle Ritenauer (BM ’11, MM ’15), Conductor Gustavo Leite (MM ’19), trumpet Changhyun Cha (MM ’20), trumpet Caleb Laidlaw (BM ’18, MM ’20), trumpet Sean Alexander (BM ’20), trumpet Imani Duhe (BM ’20), trumpet Matthew Beesmer (BM ’20), trumpet Olivia Pidi (MM ’19), trumpet Benjamin Lieberman (BM ’22), trumpet Kevin Newton (MM ’20), horn Jisun Oh (MM ’19), horn Eli Pandolfi (BM ’20), horn Liana Hoffman (BM ’20), horn Emma Potter (BM ’22), horn Kevin Casey (MM ’20), trombone Kenton Campbell (MM ’20), trombone Julia Dombroski (MM ’20), trombone David Farrell (MM ’20), trombone Morgan Fite (PS ’19), bass trombone Patrick Crider (MM ’19), bass trombone Mark Broschinsky (DMA ’11), euphonium Logan Reid (BM ’20), bass trombone Emerick Falta (BM ’21), tuba Brandon Figueroa (BM ’20), tuba Cooper Martell (BM ’20), percussion Hyunjung Choi (BM ’19), percussion Tae McLoughlin (BM ’20), percussion Hamza Able (BM ’20), percussion Introduction Monica Coen Christensen, Dean of Students Greetings Lorraine Gallard, Chair of the Board of Trustees James Gandre, President Presentation of Commencement Awards Laura Sametz, Member of the Musical Theatre faculty and the Board of Trustees Musical Interlude GEORGE LEWIS Artificial Life 2007 (b. 1952) Paul Mizzi (MM ’19), flute Wickliffe Simmons (MM ’19), cello Edward Forstman (MM ’19), piano Thomas Feng (MM ’19), piano Jon Clancy (MM ’19), percussion Presentation of the President’s Medal for Distinguished Service President Gandre Joyce Griggs, Executive Vice President and Provost John K. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

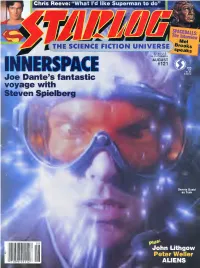

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

0ML SPOKANE DLYQ6.STY (Page 2)

(S) = In Stereo (N) = NewProgramming For 24-hour television listings, plus a guide to channel numbers on cable Tonight’s listings (HD) = High Definition Television (PA) = Parental Advisory Movies shaded Listings subject to change and satellite, look in the TV Week magazine in Sunday’s Spokesman-Re- (R) = Restricted Under 17 (NR) = Not Rated view. 5 pm 5:30 6 pm 6:30 7 pm 7:30 8 pm 8:30 9 pm 9:30 10 pm 10:30 11 pm 11:30 12 am KREM News (N) CBS Evening News- News (N) Access Hollywood The Doctors 4 The Big Bang The- How I Met Your Two and a Half Rules of Engage- CSI: Miami: Collateral Damage. (N) (S) 5 News (N) (:35) Late Show With David Letterman ^/2.1 Couric (N) 4 ory 4 Mother 5 Men 5 ment 5 (HD) (N) (S) 4 (HD) KXLY KXLY 4 News at 5 World News-Gib- KXLY 4 News at 6 KXLY 4 News at Entertainment The Insider (N) (S) Dancing With the Stars: The celebrities perform. (Same-day Tape) (S) 4 (HD) (:02) Castle: Little Girl Lost. (N) (S) 4 KXLY 4 News at 11 Nightline (HD) Jimmy Kimmel Live 4.1/4.3 (HD) son (HD) 6:30 (HD) Tonight 4 4 (HD) (HD) (HD) 5 KXMN News Storm Stories 3 Cops (S) 4 Cops (S) 4 News News Masters of Illusion (N) (S) (HD) Magic’s Biggest Secrets Finally Re- Entertainment The Insider (N) (S) Inside Edition 4 FX 2 (‘91, Action) (Bryan Brown, Rachel 4.2 vealed (N) (S) (HD) Tonight 4 4 (HD) Ticotin) (PG-13) KHQ News (N) 3 NBC Nightly News News (N) 3 Who Wants to Be a Jeopardy! (N) 3 Wheel of Fortune Deal or No Deal (N) (S) 4 Medium: How to Make a Killing in Big Business. -

Writer/Producer Of

A Q&A with Bryan Cogman: An Evening with BELLA GAIA Writer/Producer of Marc Shaiman Beautiful Earth “Game of Thrones” Join us for “An Evening with Marc Shaiman” — part BELLA GAIA is an unprecedented NASA-powered performance, part music master class, part stories immersive experience, inspired by astronauts who Bryan Cogman has an overall deal at Amazon Stu - from the movies and Broadway, and ALL entertain - spoke of the life-changing power of seeing the dios where he's developing content exclusively for ing! You won’t want to miss this celebration of Earth from space. Illuminating the beauty of the the streaming platform's television network. He music in the movies from the master musician and planet — both natural and cultural (BELLA) and the was a Consulting Producer on Amazon's highly-an - composer himself! Marc Shaiman has worked with interconnectedness of all things on Earth (GAIA) — ticipated “Lord of the Rings” television series and is and composed music for the “who’s who” of Holly - this live concert blends music, dance, technology, currently developing his own show for the stream - wood and Broadway and has created the sound - and NASA satellite imagery to turn the stage plane - ing network. track of dozens of our favorite films and musicals! tary. He is going to take you on a musical journey behind Before inking his deal with Amazon, Bryan was a the scenes of some of his biggest smash hits! A visceral flow of unencumbered beauty manifests Co-Executive Producer and Writer on the HBO for all the senses by combining supercomputer megahit, “Game of Thrones”.