In Seeking a Definition of Mash: Ttitudea in Musical Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTBA Band Scramble at Threadgill's North

Volume 37, No. 7 Copyright © Central Texas Bluegrass Association July 2015 Sunday, July 5: CTBA Band Scramble at Threadgill’s North By Eddie Collins up. It’s that time again. It’s the CTBA’s 19th annual garage sale and band scramble, Sun- Y day, July 5, 2-6 PM at Threadgill’s North, 6416 N. Lamar. The garage sale portion of the event will be where the buffet is usually set up. We’ll have CDs, instructional materials and other music related items, and T-shirts (didn’t make it out to the RayFest? Here’s your second chance to get a RayFest T-shirt at a bargain price). The second part of the event is the band scramble, where up to 40 area (continued on page 3) The weather in Texas is as changeable as a chameleon on a rain gauge. One year it’s a drought, next year it’s monsoon season. But don’t let that stop you from scrambling out to Threadgill’s on July 5. If you miss it, you’ll be green with envy. Photo by K. Brown. Jamming at the 2012 CTBA band scramble; Waterloo Ice House, June 1, 2012. Left to right: Jeff Robertson, Jacob Roberts, Matt Downing. Photo by K. Brown. July birthdays: Jeff Autry, Byron Berline, Ronnie Bowman, Sidney Cox, Dave Evans, Bela Fleck, Jimmy Gaudreau, Bobby Hicks, Jim Hurst, Alison Krauss, Andy Leftwich, Everett Lilly, Larry McPeak, Jesse McReynolds, Charlie Monroe, Scott Nygaard, Molly O’Day, Peter Rowan, Allan Shelton, Valerie Smith, Bobby Thompson, Jake Tullock, Rhonda Vincent, Keith Whitley… oh, and also the United States. -

Ross Nickerson-Banjoroadshow

Pinecastle Recording Artist Ross Nickerson Ross’s current release with Pin- ecastle, Blazing the West, was named as “One of the Top Ten CD’s of 2003” by Country Music Television, True West Magazine named it, “Best Bluegrass CD of 2003” and Blazing the West was among the top 15 in ballot voting for the IBMA Instrumental CD of the Year in 2003. Ross Nickerson was selected to perform at the 4th Annual Johnny Keenan Banjo Festival in Ireland this year headlined by Bela Fleck and Earl Scruggs last year. Ross has also appeared with the New Grass Revival, Hot Rize, Riders in the Sky, Del McCoury Band, The Oak Ridge Boys, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and has also picked and appeared with some of the best banjo players in the world including Earl Scruggs, Bela Fleck, Bill Keith, Tony Trischka, Alan Munde, Doug Dillard, Pete Seeger and Ralph Stanley. Ross is a full time musician and on the road 10 to 15 days a month doing concerts , workshops and expanding his audience. Ross has most recently toured England, Ireland, Germany, Holland, Sweden and visited 31 states and Canada in 2005. Ross is hard at work writing new material for the band and planning a new CD of straight ahead bluegrass. Ross is the author of The Banjo Encyclopedia, just published by Mel Bay Publications in October 2003 which has already sold out it’s first printing. For booking information contact: Bullet Proof Productions 1-866-322-6567 www.rossnickerson.com www.banjoteacher.com [email protected] BLAZING THE WEST ROSS NICKERSON 1. -

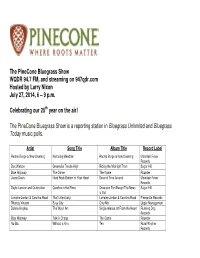

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Rachel Burge & New Dawning Kentucky Mandolin Rachel Burge & New Dawning Mountain Fever Records Doc Watson Greenville Trestle High Riding the Midnight Train Sugar Hill Blue Highway The Game The Game Rounder Jason Davis Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart Second Time Around Mountain Fever Records Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Carolina in the Pines Once and For Always/The News Sugar Hill is Out Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road That’s Kentucky Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road Pinecastle Records Rhonda Vincent Busy City Only Me Upper Management Donna Hughes The Way I Am Single release off From the Heart Running Dog Records Blue Highway Talk is Cheap The Game Rounder Nu-Blu Without a Kiss Ten Rural Rhythm Records Kruger Brothers Streamlined Cannonball Remembering Doc Watson Double Time Music The Seldom Scene With Body and Soul The Best of The Seldom Scene Rebel Records Darrell Webb Band Folks Like Us Dream Big Mountain Fever Records Seldom Scene Wait a Minute (feat. John Starling) Long Time… Seldom Scene Smithsonian/Folkwa ys Becky Buller Southern Flavor ’Tween Earth & Sky Dark Shadow Recording Sideline Girl at the Crossroads Bar Session I Mountain Fever Records Dolly Parton Blue Smoke Blue Smoke Sony Masterworks The Gentlemen of Bluegrass Carolina Memories Carolina Memories Pinecastle Records Richard Bennett Wayfaring Stranger (feat. -

Cowpie Lessons

I. Basic Theory A. Major scale and Intervals COPYRIGHT AND DISCLAIMER The Cowpie Guitar Lessons are Copyright 1995 by Greg Vaughn. Lessons are Written by Greg Vaughn and typeset in BoChord 0.94 which is Copyright 1995 by Harold "Bo" Baur. The material included in this series of lessons is not guaranteed to be correct. It should be considered guidelines used in Western music - Western as in Western Hemisphere, rather than songs of the American West. The "rules" given here were much more strictly adhered to in the period of classical music, however they still serve as useful "rules of thumb" in 20th century music. They are probably true 90% to 95% of the time in Country styles. As you all probably know, music is based on scales. Scales are based on patterns of notes called intervals. Chords are built by playing a combination of notes from a scale. The smallest unit of "distance" between notes is the half-step, By "distance" I mean difference in frequency between notes which relates to a true distance on the fretboard on a guitar. The distance between any two adjacent frets is a half-step. Each note is represented by a letter from A to G. The distance between any two consecutive letters is a whole step - or two half-steps - EXCEPT for the distance between B and C, and E and F which are half-steps. A sharp sign (#) means to play the note one half-step higher than usual and a flat sign (b) means to play the note one half- step lower than usual. -

Visit Us on Facebook & Twitter

PRESS RELEASE Contact: Mary Ladd Public Information Coordinator Ponca City Public Schools 580-352-4188 [email protected] #TeamPCPS #WildcatWay PCPS Big Blue Band Reports Great Results from Red Carpet Honor Band Auditions The Ponca City Senior High School Big Blue Band members participated in the Red Carpet Honor Band Auditions held on Saturday, November 16 in Chisholm, Oklahoma. The Senior High School Honor Band consists of students in grades 10th through 12th grade. The 9th grade students participated in the Junior High Honor Bands, which is made up of students in grades 7th through 9th. High schools that participated included: Alva, Blackwell, Cashion, Chisholm, Cimarron, Covington-Douglas, Drummond, Enid, Fairview, Fargo-Gage, Garber, Kingfisher, Kremlin-Hillsdale, Laverne, Medford, Mooreland, Newkirk, Okeene, Oklahoma Bible Academy, Perry, Pioneer-Pleasant Vale, Ponca City, Pond Creek-Hunter, Ringwood, Seiling, Texhoma, Timberlake, Tonkawa, Waukomis, Waynoka, and Woodward. There were two Junior High Honor Bands selected, an “A” Band and a “B” Band. This is made up of students in grades 7th through 9th grade. Ponca City 9th grade students competed in the junior high area. The 17- 9th graders who earned their positions is the largest number of freshmen Ponca City has ever had make one of the two bands. Schools represented in the junior high tryouts included: Alva, Blackwell, Cashion, Chisholm, Cimarron, Covington-Douglas, Emerson (Enid), Enid, Fairview, Garber, Hennessey, Kingfisher, Kremlin-Hillsdale, Laverne, Longfellow (Enid), Medford, Mooreland, Newkirk, Okarche, Okeene, Oklahoma Bible Academy, Perry Pioneer-Pleasant Vale, Ponca City, Ponca City East, Ponca City West, Pond Creek-Hunter, Ringwood, Seiling, Texhoma, Tonkawa, Waller (Enid), Waukomis, Waynoka, and Woodward. -

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview The 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival is quickly approaching, February 14 -16 at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel, in Framingham, MA. The event, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, is one of the premier roots music festivals in the Northeast. The festival site is minutes west of Boston, just off of the Mass Pike, and convenient to travelers from throughout the region. This award winning and family friendly festival features three days of top national performers across two stages, over sixty workshops and education programs, and around the clock activities. Among the many artists on tap are The Gibson Brothers, Blue Highway, Junior Sisk, IIIrd Tyme Out, Sister Sadie featuring Dale Ann Bradley, and a special reunion performance by The Desert Rose Band. This locally produced and internationally recognized bluegrass festival, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, was honored in 2006 when the International Bluegrass Music Association named it "Event of the Year." In May 2012, the festival was listed by USATODAY as one of Ten Great Places to Go to Bluegrass Festivals Single day and weekend tickets are on sale now and we strongly suggest purchasing tickets in advance. Patrons will save time at the festival and guarantee themselves a ticket. Hotel rooms at the Sheraton are sold out, but overnight lodging is still available and just minutes away, at the Doubletree by Hilton, in Westborough, MA. Details on the festival, including bands, schedules, hotel information, and online ticket purchase at www.bbu.org And visit the 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival on Facebook for late breaking festival news. -

The Meshuggah Quartet

The Meshuggah Quartet Applying Meshuggah's composition techniques to a quartet. Charley Rose jazz saxophone, MA Conservatorium van Amsterdam, 2013 Advisor: Derek Johnson Research coordinator: Walter van de Leur NON-PLAGIARISM STATEMENT I declare 1. that I understand that plagiarism refers to representing somebody else’s words or ideas as one’s own; 2. that apart from properly referenced quotations, the enclosed text and transcriptions are fully my own work and contain no plagiarism; 3. that I have used no other sources or resources than those clearly referenced in my text; 4. that I have not submitted my text previously for any other degree or course. Name: Rose Charley Place: Amsterdam Date: 25/02/2013 Signature: Acknowledgment I would like to thank Derek Johnson for his enriching lessons and all the incredibly precise material he provided to help this project forward. I would like to thank Matis Cudars, Pat Cleaver and Andris Buikis for their talent, their patience and enthusiasm throughout the elaboration of the quartet. Of course I would like to thank the family and particularly my mother and the group of the “Four” for their support. And last but not least, Iwould like to thank Walter van de Leur and the Conservatorium van Amsterdam for accepting this project as a master research and Open Office, open source productivity software suite available on line at http://www.openoffice.org/, with which has been conceived this research. Introduction . 1 1 Objectives and methodology . .2 2 Analysis of the transcriptions . .3 2.1 Complete analysis of Stengah . .3 2.1.1 Riffs . -

Class Piano Handbook

CLASS PIANO HANDBOOK THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, KNOXVILLE COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES SCHOOL OF MUSIC DR. EUNSUK JUNG LECTURER OF PIANO COORDINATOR OF CLASS PIANO TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 3 CONTACT INFORMATION 4 COURSE OBJECTIVES CLASS PIANO I & II 5 CLASS PIANO III & IV 6 ACTIVITIES AND SKILLS INCLUDED IN CLASS PIANO 7 PIANO LAB POLICIES 8 GUIDELINES FOR EFFECTIVE PRACTICE 9 TESTING OUT OF CLASS PIANO 11 KEYBOARD PROFICIENCY TEST REQUIREMENTS CLASS PIANO I (MUKB 110) 12 CLASS PIANO II (MUKB 120) 13 CLASS PIANO III (MUKB 210) 14 CLASS PIANO IV (MUKB 220) 15 FAQs 16 UTK CLASS PIANO HANDBOOK | 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Class Piano is a four-semester course program designed to help undergraduate non- keyboard music majors to develop the following functional skills for keyboard: technique (scales, arpeggios, & chord progressions), sight-reading, harmonization, transposition, improvisation, solo & ensemble playing, accompaniment, and score reading (choral & instrumental). UTK offers four levels of Class Piano in eight different sections. Each class meets twice a week for 50 minutes and is worth one credit hour. REQUIRED COURSES FOR MAJORS Music Education with Instrumental MUKB 110 & 120 Emphasis (Class Piano I & II) Music Performance, Theory/Composition, MUKB 110, 120, 210, & 220 Music Education with Vocal Emphasis (Class Piano I, II, III, & IV) CLASS PIANO PROFICIENCY EXAM Proficiency in Keyboard skills is usually acquired in the four-semester series of Class Piano (MUKB 110, 120, 210, & 220). To receive credit for Class Piano, students must register for, take, and pass each class. Students who are enrolled in Class Piano will be prepared to meet the proficiency requirement throughout the course of study. -

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews All reviews of flatpicking CDs, DVDs, Videos, Books, Guitar Gear and Accessories, Guitars, and books that have appeared in Flatpicking Guitar Magazine are shown in this index. CDs (Listed Alphabetically by artists last name - except for European Gypsy Jazz CD reviews, which can all be found in Volume 6, Number 3, starting on page 72): Brandon Adams, Hardest Kind of Memories, Volume 12, Number 3, page 68 Dale Adkins (with Tacoma), Out of the Blue, Volume 1, Number 2, page 59 Dale Adkins (with Front Line), Mansions of Kings, Volume 7, Number 2, page 80 Steve Alexander, Acoustic Flatpick Guitar, Volume 12, Number 4, page 69 Travis Alltop, Two Different Worlds, Volume 3, Number 2, page 61 Matthew Arcara, Matthew Arcara, Volume 7, Number 2, page 74 Jef Autry, Bluegrass ‘98, Volume 2, Number 6, page 63 Jeff Autry, Foothills, Volume 3, Number 4, page 65 Butch Baldassari, New Classics for Bluegrass Mandolin, Volume 3, Number 3, page 67 William Bay: Acoustic Guitar Portraits, Volume 15, Number 6, page 65 Richard Bennett, Walking Down the Line, Volume 2, Number 2, page 58 Richard Bennett, A Long Lonesome Time, Volume 3, Number 2, page 64 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), This Old Town, Volume 4, Number 4, page 70 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), Blue Lonesome Wind, Volume 5, Number 6, page 75 Gonzalo Bergara, Portena Soledad, Volume 13, Number 2, page 67 Greg Blake with Jeff Scroggins & Colorado, Volume 17, Number 2, page 58 Norman Blake (with Tut Taylor), Flatpickin’ in the -

Bluegrass Outlet Banjo Tab List Sale

ORDER FORM BANJO TAB LIST BLUEGRASS OUTLET Order Song Title Artist Notes Recorded Source Price Dixieland For Me Aaron McDaris 1st Break Larry Stephenson "Clinch Mountain Mystery" $2 I've Lived A Lot In My Time Aaron McDaris Break Larry Stephenson "Life Stories" $2 Looking For The Light Aaron McDaris Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 1st Break Mashville Brigade $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Mashville Brigade $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Philadelphia Lawyer Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again Aaron McDaris Intro & B/U 1st verse Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Leaving Adam Poindexter 1st Break James King Band "You Tube" $2 Chatanoga Dog Alan Munde Break C-tuning Jimmy Martin "I'd Like To Be 16 Again" $2 Old Timey Risin' Damp Alan O'Bryant Break Nashville Bluegrass Band "Idle Time" $4 Will You Be Leaving Alison Brown 1st Break Alison Kraus "I've Got That Old Feeling" $2 In The Gravel Yard Barry Abernathy Break Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver "Never Walk Away" $2 Cold On The Shoulder Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On The Shoulder" $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 1st Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 2nd Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 The Likes Of Me Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On -

Jan/Feb/Mar 2021 Winter Express Issue

Vol. 41 No. 1 INSIDE THIS ISSUE! Jan. Feb. Mar. Taborgrass: Passing e Torch, Helen Hakanson: Remembering A 2021 Musical LIfe and more... $500 Oregon Bluegrass Association Oregon Bluegrass Association www.oregonbluegrass.org By Linda Leavitt In March of 2020, the pandemic hit, and in September, two long-time Taborgrass instructors, mandolinist Kaden Hurst and guitarist Patrick Connell took over the program. ey are adamant about doing all they can to keep the spirit of Taborgrass alive. At this point, they teach weekly Taborgrass lessons and workshops via Zoom. ey plan to resume the Taborgrass open mic online, too. In the future, classes will meet in person, once that becomes feasible. et me introduce you to Kaden Kaden has played with RockyGrass (known as Pat), e Hollerbodies, and Hurst and Patrick Connell, the 2019 Band Competition winners Never Julie & the WayVes. Lnew leaders of Taborgrass. In 2018, Patrick As a mandolinist met Kaden at born in the ‘90s, Taborgrass, and Kaden was hugely started meeting inuenced by to pick. Kaden Nickel Creek. became a regular Kaden says that at Patrick’s Sunday band shied Laurelirst his attention to Bluegrass Brunch bluegrass. Kaden jam. According was also pulled to Patrick, “One closer to “capital B Sunday, Joe bluegrass” by Tony Suskind came to Rice, most notably the Laurelirst by “Church Street jam and brought Blues,” and by Brian Alley with Rice’s duet album him. We ended with Ricky Skaggs, Kaden Hurst and Patrick Connell up with this little “Skaggs and Rice.” group called e Kaden’s third major Come Down, Julie and the WayVes, Portland Radio Ponies. -

Ron Block Hogan's House of Music Liner Notes Smartville (Ron Block

Ron Block Hogan’s House of Music Liner Notes Smartville (Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Tim Crouch - fiddle Jerry Douglas - Dobro Stuart Duncan – fiddle Clay Hess - rhythm guitar Adam Steffey – mandolin Hogan’s House of Boogie (Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Ron Block – banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Sam Bush - mandolin Jerry Douglas – Dobro Byron House - bass Dan Tyminski – rhythm guitar Lynn Williams – snare Wolves A-Howling (Traditional) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo Stuart Duncan - fiddle Adam Steffey - mandolin Dan Tyminski - rhythm guitar The Spotted Pony (Traditional, arr. Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Stuart Duncan – fiddle Sierra Hull – octave mandolin Alison Krauss - fiddle Adam Steffey – mandolin Dan Tyminski - rhythm guitar Lynn Williams – snare Clinch Mountain Backstep (Ralph Stanley) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Stuart Duncan – fiddle Clay Hess - rhythm guitar Adam Steffey – mandolin Gentle Annie (Stephen Foster) Ron Block – banjo, guitar Tim Crouch – fiddles, cello, bowed bass Mark Fain - bass Sierra Hull – octave mandolins Mooney Flat Road (Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Stuart Duncan – fiddle Sierra Hull – octave mandolin Alison Krauss - fiddle Adam Steffey – mandolin Jeff Taylor - accordion Dan Tyminski - rhythm guitar Lynn Williams – snare Mollie