September 2013 Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England Athletics Under 23 & Under 20 Championships 22

ENGLAND ATHLETICS UNDER 23 & UNDER 20 CHAMPIONSHIPS 22 & 23 JUNE 2019 @ BEDFORD RESULTS 400m Hurdles U20 Women AGE GROUP BEST: Shona Richards, Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow, 56.16, 2014 CBP: Vicki Jamison, Lagan Valley AC, 57.27, 1996 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 1 1 1114 Marcey Winter Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 60.58 Q 2 819 Steph Driscoll Liverpool Harriers & AC 61.72 Q 3 1086 Grace VansAgnew Crawley AC 62.26 Q 4 796 Jasmine Clark Middlesbrough Athletic Club (Mandale) 62.47 q 5 853 Neve Grimes Charnwood AC 64.96 6 798 Ellie Cleveland Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 65.30 7 885 Kati Hulme Shrewsbury AC 65.84 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 2 1 768 Orla Brennan Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 60.82 Q 2 897 Jasmine Jolly Birchfield Harriers 61.37 Q 3 909 Jessica Lambert Crawley AC 61.42 Q 4 1021 Louise Robinson Birchfield Harriers 63.28 q 5 732 Olivia Allbut Jersey Spartan AC 67.80 6 1102 Rebecca Watkins Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 68.03 DQ 946 Meg McHugh Trafford Athletic Club Rule 168.7a 400m Hurdles U23 Women AGE GROUP BEST: Sally Gunnell, Essex Ladies AC, 54.03, 1988 CBP: Perri Shakes-Drayton, Victoria Park & Tower Hamlets, 55.34, 2009 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 1 1 1090 Chelsea Walker City of York AC 61.48 Q 2 806 Emily Craig Edinburgh AC 61.68 Q 3 954 Jasmine Mitchell Loughborough Students 63.25 Q 4 1005 Ellie Ravenscroft Kidderminster and Stourport 63.96 q 5 906 Hannah Knights Guildford & Godalming AC 64.65 q 6 827 Sophie Elliss Croydon Harriers 65.00 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 2 1 1112 Lauren Williams -

Powerlifter to Bodybuilder: Matt Kroc Mark Bell Sits Down with Kroc to Get the Story Behind His Amazing Physique and His Journey Toward Becoming a Pro Bodybuilder

240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 1 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 SEP/OCT 2012 • VOL. 3, NO. 5 Content is copyright protected and provided for personal use only - not for reproduction or retransmission. For reprints please contact the Publisher. 240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 2 Content is copyright protected and provided for personal use only - not for reproduction or retransmission. For reprints please contact the Publisher. 240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 3 Content is copyright protected and provided for personal use only - not for reproduction or retransmission. For reprints please contact the Publisher. 240SEP12_001-033.qxp 8/16/12 7:36 AM Page 4 MAGAZINE VOLUME 3 • ISSUE 5 PUBLISHER Andee Bell POWER: YOUR WEAPON AGAINST WEAKNESS [email protected] EDITOR-AT-XTRA-LARGE ’m going to give myself a much needed pat on the back (if I can figure out how to reach it). Mark Bell • [email protected] For my wifey, the publisher, I’ll give her a much needed spank on the ass for yet another job Iwell done with Power. Yes, she gets spanked whether she’s good or bad. Also, not to brag, MANAGING EDITOR (OK here comes some bragging) but we are the only strength/powerlifting publication in the Heather Peavey world and we will continue to grow and expand. Power is devoted and honored to be your strength manual and your ultimate weapon against weakness! ASSOCIATE EDITOR I’d like to welcome a new addition to the Sling Shot family, Sam McDonald. -

All Time Historical Men and Women's

ALL TIME HISTORICAL MEN AND WOMEN’S POWERLIFTING WORLD RECORDS Listing Compiled by Michael Soong i TABLE OF CONTENTS MEN’S WORLD RECORDS All Time Historical Men’s Powerlifting World Records In Pounds/Kilograms ________________________ 3 All Time Historical Men’s Powerlifting World Rankings In Pounds ___________________________________ 4 All Time Historical Men’s Unequipped Powerlifting World Records In Pounds/Kilograms ______________ 5 All Time Historical Men’s Unequipped Powerlifting World Rankings In Pounds _________________________ 7 Men’s 1100 Pound (499.0 Kilogram) Squat Hall Of Fame ___________________________________________ 8 Men’s 900 Pound (408.2 Kilogram) Unequipped Squat Hall Of Fame __________________________________ 9 Men’s Quintuple Bodyweight Squat Hall Of Fame _________________________________________________ 9 Men’s 900 Pound (408.2 Kilogram) Bench Press Hall Of Fame _______________________________________ 10 Men’s 600 Pound (272.2 Kilogram) Unequipped Bench Press Hall Of Fame _____________________________ 11 Men’s Triple Bodyweight Unequipped Bench Press Hall Of Fame _____________________________________ 12 Men’s 900 Pound (408.2 Kilogram) Deadlift Hall Of Fame __________________________________________ 13 Men’s 12x Bodyweight Total Hall Of Fame ______________________________________________________ 14 Men’s 2700 Pound (1224.7 Kilogram) Total Hall Of Fame __________________________________________ 15 WOMEN’S WORLD RECORDS All Time Historical Women’s Powerlifting World Records In Pounds/Kilograms ______________________ -

Downloadable Results (Pdf)

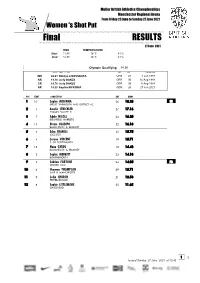

Muller British Athletics Championships Manchester Regional Arena Heptathlon From Friday 25 June to Sunday 27 June 2021 Women 's Shot Put LETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS RESULTS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS 26 June 2021 TIME TEMPERATURE Start 15:30 14°C 78 % End 15:5214°C 78 % MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date WR22.63 Natalya LISOVSKAYA URS 24 7 Jun 1987 NR19.36 Judy OAKES GBR 30 14 Aug 1988 CR18.76 Judy OAKES GBR 30 6 Aug 1988 SR17.88 Sophie MCKINNA GBR 26 4 Sep 2020 POSSTART COMPETITOR AGE MARK POINTS 1 3 Ellen BARBER 23 13.30 747 YEOVIL 2 6 Katie STAINTON 26 12.02 662 SB BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 3 2 Natasha SMITH 21 12.01 662 SB BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 4 8 Ashleigh SPILIOPOULOU 22 10.88 587 ENFIELD & HARINGEY H 5 7 Ella RUSH 17 10.54 565 AMBER VALLEY 6 5 Emily TYRRELL 19 9.43 492 TEAM BATH 7 1 Emma CANNING 24 8.18 411 EDINBURGH AC 4 Amaya SCOTT-RULE 20 DNS 0 SOUTHAMPTON SERIES 1 2 3 1 Emma CANNING EDAC X 8.18 X 2 Natasha SMITH BIRCHFIELD 11.57 12.01 11.45 3 Ellen BARBER YEOVIL 13.09 13.22 13.30 4 Amaya SCOTT-RULE SOTON 5 Emily TYRRELL BATH X 8.70 9.43 6 Katie STAINTON BIRCHFIELD 12.02 11.98 X 7 Ella RUSH AMBER V 10.54 X X 8 Ashleigh SPILIOPOULOU ENFIELD 10.88 10.83 10.27 GREAT BRITAIN & N.I. -

Downloadable Results (Pdf)

Muller British Athletics Championships Manchester Regional Arena From Friday 25 June to Sunday 27 June 2021 Women 's Shot Put HLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS Final RESULTS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS A 27 June 2021 TIME TEMPERATURE Start 11:38 16°C 81 % End 12:3816°C 81 % Olympic Qualifying 18.50 MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date WR22.63 Natalya LISOVSKAYA URS 24 7 Jun 1987 NR19.36 Judy OAKES GBR 30 14 Aug 1988 CR18.76 Judy OAKES GBR 30 6 Aug 1988 SR18.28 Sophie MCKINNA GBR 26 27 Jun 2021 POSSTART COMPETITOR AGE MARK 1 10 Sophie MCKINNA 26 18.28 SR GREAT YARMOUTH AND DISTRICT AC 2 5 Amelia STRICKLER 27 17.16 THAMES VALLEY H 3 7 Adele NICOLL 24 16.20 BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 4 11 Divine OLADIPO 22 16.18 BLACKHEATH & BROMLEY 5 3 Eden FRANCIS 32 15.75 LEICESTER 6 4 Serena VINCENT 19 15.71 C OF PORTSMOUTH 7 12 Nana GYEDU 18 14.48 BLACKHEATH & BROMLEY 8 2 Sophie MERRITT 23 14.18 BOURNEMOUTH 9 1 Sabrina FORTUNE 24 14.05 PB DEESIDE AAC 10 6 Shaunna THOMPSON 29 13.71 SALE H MANCHESTER 11 9 Lydia CHURCH 21 12.53 PETERBOROUGH 12 8 Sophie LITTLEMORE 25 11.65 GATESHEAD 1 2 Issued Sunday, 27 June 2021 at 12:42 Shot Put Women - Final RESULTS SERIES 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Sabrina FORTUNE DEESIDE 13.62 14.05 13.15 -

Women's 60 Metres

European Indoor Athletics Championships 2019 • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 60 Metres 46 Entrants Event starts: March 2 Countries Age (Days) Born SB PB 511 TOTH Alexandra AUT 23y 244d 1995 7.33 7.33 -18/19 Twice Austrian Champion at both 60m & 100m // 100 pb: 11.43 -18. 200 pb: 23.65 -18. ht WJC 100 2014; ht ECH 100 2018. 1 Austrian 100 2016/2018 (1 200 2018). 1 Austrian indoor 60 2018/2019, 200 2018 In 2019: 1 Vienna Hallen 60; 1 Vienna Erima 60/200; 2 Erfurt 60; 1 Vienna Gala 60; 1 Linz 60; 1 Austrian indoor 60 513 HASANOVA Zakiyya AZE 23y 187d 1995 7.37 7.37 -19 Holder of all Azeri women’s sprint records, indoors & out // 100 pb: 11.61 -18. 200 pb: 23.64 -18 (24.79i -19). 1 Small European States Games 200 2018 (2 100). 1 Azeri 100/200 2017 & indoor 60/200 2019 In 2019: 1 Baku 60/200; 1 Azeri indoor 60/200; 5 Balkan indoor 60; 3 Istanbul Cup 60 533 TSIMANOUSKAYA Krystsina BLR 22y 100d 1996 7.21 7.21 -17 (aka Kristina Timanovskaya) 2017 European under-23 silver at 100m 100 pb: 11.04 -18. 200 pb: 22.92 -18. 12 ETCh 200 2015; 6 EJC 100 2015; sf EIC 60 2017; 5 ETCh 100/200 2017; 2 under-23 ECH 100 2017 (4 200); ht WIC 60 2018; sf ECH 100 100/200 2018. 1 Belarusian 100/200 2016/2017/2018; 1 Belarusian indoor 60 2017/2018 (1 200 2017/2019) In 2019: 1 Minsk 60; 1 Belarusian indoor 200 (2 60); 1 Val-de-Reuil 60; 3 Łódź 60; 4 Liévin 60; 3 Eaubonne 60 541 ANDREOU Paraskevi CYP 22y 44d 1997 7.40 7.40 -19 2014 Youth Olympic silver at 100m // 100 pb: 11.65 -14. -

All Time Historical Men and Women's Powerlifting

ALL TIME HISTORICAL MEN AND WOMEN’S POWERLIFTING WORLD RECORDS Listing Compiled by Michael Soong i TABLE OF CONTENTS MEN’S WORLD RECORDS All Time Historical Men’s Powerlifting World Records In Pounds/Kilograms ________________________ 3 All Time Historical Men’s Powerlifting World Rankings In Pounds ___________________________________ 4 All Time Historical Men’s Unequipped Powerlifting World Records In Pounds/Kilograms ______________ 5 All Time Historical Men’s Unequipped Powerlifting World Rankings In Pounds _________________________ 7 Men’s 1200 Pound (499.0 Kilogram) Squat Hall Of Fame ___________________________________________ 8 Men’s 900 Pound (408.2 Kilogram) Unequipped Squat Hall Of Fame __________________________________ 9 Men’s Quintuple Bodyweight Squat Hall Of Fame _________________________________________________ 11 Men’s 900 Pound (408.2 Kilogram) Bench Press Hall Of Fame _______________________________________ 12 Men’s 600 Pound (272.2 Kilogram) Unequipped Bench Press Hall Of Fame _____________________________ 13 Men’s Triple Bodyweight Unequipped Bench Press Hall Of Fame _____________________________________ 16 Men’s 900 Pound (408.2 Kilogram) Deadlift Hall Of Fame __________________________________________ 17 Men’s 12x Bodyweight Total Hall Of Fame ______________________________________________________ 18 Men’s 2700 Pound (1224.7 Kilogram) Total Hall Of Fame __________________________________________ 20 Men’s 2204.6 Pound (1000.0 Kilogram) Unequipped Total Hall Of Fame _______________________________ 21 WOMEN’S WORLD -

Aviva England Athletics U23 & U20 Championships

AVIVA ENGLAND ATHLETICS U23 & U20 CHAMPIONSHIPS & EUROPEAN TRIALS 25-26th June 2011 @ Bedford Stadium U23 Men T12 U23M 100m - Heats UK Best : Dwain Chambers, Belgrave Harriers, 9.97, 1999 CBP Jonathan Barbour, Blackheath H, 10.13, 2001 HEAT 1 WS = +6.1m/s Posn BIB ATHLETE CLUB Perf 1 22 James ALAKA Blackheath & Bromley AC 10.25 Q 2 7 Charlie DACK Loughborough/Southend AC 10.44 Q 3 76 Richard ODUMOSU Shaftesbury Barnet Harriers 10.59 Q 4 58 Jordan HUGGINS Enfield & Haringey AC 10.60 q 5 25 Saul PAINE Victoria Park H 10.85 q 6 53 Chaka MAILLET Thames Valley H 11.14 7 17 Alex OJO Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow DQ HEAT 2 WS = +3.1m/s Posn BIB ATHLETE CLUB Perf 1 32 Deji TOBAIS Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow 10.37 Q 2 1 Ryan OSWALD Sale Harriers Manchester 10.58 Q 3 973 Gareth PRICE Cardiff AAC 10.71 Q 4 41 Ricky REEVES City of Sheffield AC 10.72 q 5 50 Moses BAWO Thames Valley H 10.95 6 52 Errol HOUSTON Enfield & Haringey AC DQ HEAT 3 WS = +2.8m/s Posn BIB ATHLETE CLUB Perf 1 11 Andrew ROBERTSON Sale Harriers Manchester 10.47 Q 2 28 Olufunmi SOBODU Blackheath & Bromley AC 10.74 Q 3 971 Rashid KAKOZZA Newham & Essex Beagles AC 10.80 Q 4 55 William DE TORVY Thames Valley H 10.90 5 18 Jamie BROCK Yate AC 11.14 6 73 Santino DUMMETT Telford AC 11.19 HEAT 4 WS = +3.1 m/s Posn BIB ATHLETE CLUB Perf 1 40 Kieran SHOWLER-DAVIS Basingstoke 10.50 Q 2 29 Eugene AYANFUL Woodford Green & Essex L 10.51 Q 3 2 Greg CACKETT Belgrave Harriers 10.56 Q 4 26 Jeffrey OCRAH Herne Hill Harriers 10.81 q 5 122 Ryan FARRINGTON Birchfield Harriers 11.05 6 19 Adam MOHAMMED -

Men's 200M Diamond Discipline 26.08.2021

Men's 200m Diamond Discipline 26.08.2021 Start list 200m Time: 21:35 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Eseosa Fostine DESALU ITA 19.72 20.13 20.29 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 20.08.09 2 Isiah YOUNG USA 19.32 19.86 19.99 AR 19.72 Pietro MENNEA ITA Ciudad de México 12.09.79 3 Yancarlos MARTÍNEZ DOM 20.17 20.17 20.17 NR 19.98 Alex WILSON SUI La Chaux-de-Fonds 30.06.19 WJR* 19.84 Erriyon KNIGHTON USA Hayward Field, Eugene, OR 27.06.21 4Aaron BROWN CAN19.6219.9519.99WJR 19.88 Erriyon KNIGHTON USA Hayward Field, Eugene, OR 26.06.21 5Fred KERLEY USA19.3219.9019.90MR 19.50 Noah LYLES USA 05.07.19 6Kenneth BEDNAREKUSA19.3219.6819.68DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Boudewijnstadion, Bruxelles 16.09.11 7 Steven GARDINER BAH 19.75 19.75 20.24 SB 19.52 Noah LYLES USA Hayward Field, Eugene, OR 21.08.21 8William REAIS SUI19.9820.2420.26 2021 World Outdoor list 19.52 +1.5 Noah LYLES USA Eugene, OR (USA) 21.08.21 Medal Winners Road To The Final 19.62 -0.5 André DE GRASSE CAN Olympic Stadium, Tokyo (JPN) 04.08.21 1Aaron BROWN (CAN) 25 19.68 -0.5 Kenneth BEDNAREK USA Olympic Stadium, Tokyo (JPN) 04.08.21 2021 - The XXXII Olympic Games 2Kenneth BEDNAREK (USA) 23 19.81 +0.8 Terrance LAIRD USA Austin, TX (USA) 27.03.21 1. André DE GRASSE (CAN) 19.62 3André DE GRASSE (CAN) 21 19.84 +0.3 Erriyon KNIGHTON USA Eugene, OR (USA) 27.06.21 2. -

NATIONAL JUNIOR RECORDS Compiled by Milan Skočovský, ATFS

NATIONAL JUNIOR RECORDS Compiled by Milan Skočovský, ATFS 100 Metres AFG 11.21 Abdul Latif Wahidi Makkah 12 Apr 05 AHO 10.29 +0.8 Churandy Martina, 030784 Saint George´s 4 Jul 03 AIA 11.02 Kieron Rogers São Paulo 6 Jul 07 ALB 11.02 Admir Bregu Komotini 24 Jul 99 10.6 Gilman Lopci Korce 23 May 79 ALG 10.64 Mustapha Kamel Selmi Casablanca 21 Jul 84 10.3 Ali Bakhta El Djezair 24 Jun 80 AND 11.20 +0.3 Ángel Miret Gutierrez, 89 Banská Bystrica 21 Jun 08 11.08* Jose Benjamin Aguilera San Sebastian 29 Jul 06 ANG 10.86 Orlando Tungo Lisboa 4 Jul 07 10.6 Afonso Ferraz Luanda 22 May 82 10.6 Afonso Ferraz Luanda 11 Jun 83 ANT 10.19 +1.6 Daniel Bailey, 090986 Grosseto 13 Jul 03 9.9 +1.9 Brendan Christian, 111283 San Antonio 29 Apr 02 ARG 10.57 +1.4 Matías Roberto Fayos, 280180 Buenos Aires 30 Oct 99 10.3 Gerardo Bönnhoff, 240626 Buenos Aires 1 Dec 45 ARM 10.61 Hovhannes Mkrtchyan Moskva 18 Jun 91 10.3 Artush Simonyan Artashat 17 Aug 03 ARU 10.79 Miguel Janssen San Juan 23 Jul 89 ASA 11.43 Folauga Tupuola Apia 6 Jun 03 11.1 Busby Loto Tereora 3 May 95 AUS 10.29 +1.2 Matt Shirvington, 251078 Sydney 11 Oct 97 10.0 +1.1 Paul Narracott, 081059 Brisbane 19 Mar 78 AUT 10.48 +1.6 Bernd Chudarek, 89 Amstetten 7 Jun 08 AZE 10.08 +1.3 Ramil Guliyev, 290590 Istanbul 13 Jun 09 BAH 10.34 Derrick Atkins Olathe 23 May 03 10.0 Alonzo Hines Nassau 11 Apr 02 BAN 10.61 Bimal Chandra Tarafdar Dhaka 24 Dec 93 BAR 10.08A +1.9 Obadele Thompson, 300376 El Paso 16 Apr 94 BDI 10.7 Aimable Nkurunziva Bujumbura 13 Mar 85 BEL 10.39 Julien Watrin Mannheim 3 Jul 10 BEN 10.58 +0.2 -

Etn1961 Vol07 23 USA Ch

;./ \ .:~~ ,:'.'11 - ~ - \ ,ti' tr.•· 7 - 1 ·i_o,. / ~~i-.t/ f - __., ~, \ , ,l, ., t -: , ) ' . , '" J . ,. - - ' '>·, '.RACK,NEWsttIJE ,'~ ' d'.:I ·r,'.:j, . '\ \ \ . also Kvtownas · , ,, 1- 1R~tlf ~'1~s11:rrER M-~ ,,. (oFFIC\f,,\. PU6l\C~i\ON OF ',Rti.a< t-l\li'S 0.F ~E ~Oll\.O, \l~~c,) \ ,',I • 1?,.Mis\-\e.~(~ \'AAO( 6\;o f\E\.t> ~EWS • ro 80l<· '2.90 • \..OSAlt>S, C'aifovYlia ~ a~ ,aoo: Ca{d~e.v.~~\<~O\\J Eci\-\'oy~ I t, 'l ( Vol. 7, No. 23 July 5/ 1961 Semi-Monthly ><. $6 per year by first class mail '1 [· Edited by Hal Bateman ' fage 179 ' : .• , >·NATIONAL NEWS . I,, .. SOUTHEASTERN AAU DECATHLON, Memphis .,. Tenn., June ' 16-17: Mulk:ey(un,a) ' i ') 1' (10.7, 2fl", 50 13f', 6 16½'', .51,0, 14.6, 154'3½",' 14'4¾", 22,1'3½'', ,4~43;8) 8,709 points (world tecor<J) • . / i ' I . ! ' \ . 'I . 1 . , 'ALL-.COMERS / Stanford, Galif. r;-]une 24: Halb~fg "'"{New-zealand) 4:08. 91 PhHp0tt (New Zealand) 48. 5; Snell (New Zealand) , l:52. 5; Magee (New Zealand) 9: 02. 0; Jongewaard (SCVYV) 190'9'' (HT); Bocks (USA) 226'6½' ~. · , , , . · . ·•... NATiONAL AAU, New York City, June, 24: .1-00;, Budd· (Villanova) ·9. 2 ~(world ;recorct) '; Drayton (Villanova) 9. 3; James (SC Striqers) 9. 4; Dave Styron (Salukis) 9. 5; Winder (Morgan St) 9. 6; Cook (EEAA) 9. 6; Cpllyrpo,re (Quantico) 9. 7; M4rchisotl (UCTC) 9. 7. 6 Miles,pu~- ,\ knecht (una) 28:52. 6; McArdle (NYAC) 29:16. 8; Kitt (Dayton AC) 29:49. 7; Moore (Abilene TC) 30:19, 6; Williams (UCTC) 30:26. -

Nacac Newsleter June 2016

NACAC NEWSLETTER JUNE 2016 Volume 3 Edition 1 NACAC NEWSLETER JUNE 2016 President Message 2 General Secretary 5 NACAC AA Executive Council 8 Resolution Women Commission Report 9 CADICA Cross Country 13 Championships NACAC Cross Country 15 Championships CARIFTA Games 17 Athletes of the OECS Diaspora 22 NACAC U23 El Salvador 2016 29 Visit to Cuba 30 Sponsors 36 1 NACAC NEWSLETTER JUNE 2016 Volume 3 Edition 1 PRESIDENT MESSAGE by Víctor López Therefore, as I expressed in many occasions to President Coe, to the Media and to colleagues and friends, it looks to me that we will have one of the best, if not the best year ever, as far as performances is concerned. I am not talking about the NACAC athletes only but athletes from all over the world. In other words, we will own the show in Río de Janeiro, Brazil at the 2016 Olympic Games. But in spite of the above opinion, from my part, as how great the performances have been so far, we still have to be vigilante because, for sure, we still have a problem On behalf of the NACAC Executive Council with doping in our sport and in other sports. and the NACAC Athletics Family, I would like Yes, it is important that we clean the house to extend my greetings in our newsletter of and face the challenges that we are this important year, perhaps the most experiencing but, it is more important that important in the history of our sport. There we continue to do what we do best, which is is no doubt that we are facing tough to develop our great sport and our young challenges and scandals never experienced people all over the world and at the same in the past.